Palestinian Popular Struggle: Unarmed and Participatory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Norms and Pathways Have Developed Phd Th

European civil actors for Palestinian rights and a Palestinian globalized movement: How norms and pathways have developed PhD Thesis (Erasmusmundus GEM Joint Doctorate in Political and Social Sciences from Université Libre de Bruxelles _ ULB- & Political Science and Theory from LUISS Guido Carli University, Rome) By Amro SADELDEEN Thesis advisors: Pr. Jihane SFEIR (ULB) Pr. Francesca CORRAO (Luiss) Academic Year 2015-2016 1 2 Contents Abbreviations, p. 5 List of Figures and tables, p. 7 Acknowledgement, p.8 Chapter I: Introduction, p. 9 1. Background and introducing the research, p. 9 2. Introducing the case, puzzle and questions, p. 12 3. Thesis design, p. 19 Chapter II: Theories and Methodologies, p. 22 1. The developed models by Sikkink et al., p. 22 2. Models developed by Tarrow et al., p. 25 3. The question of Agency vs. structure, p. 29 4. Adding the question of culture, p. 33 5. Benefiting from Pierre Bourdieu, p. 34 6. Methodology, p. 39 A. Abductive methodology, p. 39 B. The case; its components and extension, p. 41 C. Mobilizing Bourdieu, TSM theories and limitations, p. 47 Chapter III: Habitus of Palestinian actors, p. 60 1. Historical waves of boycott, p. 61 2. The example of Gabi Baramki, p. 79 3. Politicized social movements and coalition building, p. 83 4. Aspects of the cultural capital in trajectories, p. 102 5. The Habitus in relation to South Africa, p. 112 Chapter IV: Relations in the field of power in Palestine, p. 117 1. The Oslo Agreement Period, p. 118 2. The 1996 and 1998 confrontations, p. -

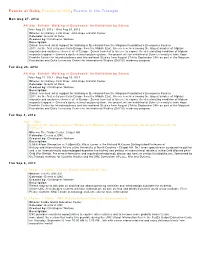

Event Archives August 2014 - July 2015 Carolina Center for the Study of the Middle East and Muslim Civilizations

Event Archives August 2014 - July 2015 Carolina Center for the Study of the Middle East and Muslim Civilizations Events at Duke, Events at UNC, Events in the Triangle Tues, Aug 19 – Fri, Visual Reactions: A View from the Middle East Oct 31, 2014 Time: August 19, 2014 - October 31, 2014, building hours weekdays 7:30am-9:00pm Location: FedEx Global Education Center UNC Chapel Hill Categories: Art, Exhibit Description: “Visual Reactions: A View from the Middle East” features more than 20 illustrations by Kuwaiti artist and graphic designer Mohammad Sharaf. Inspired by current events, Sharaf’s designs address controversial political and social topics. Sharaf’s illustrations will be on display in the UNC FedEx Global Education Center from Aug. 19 to Oct. 31. The exhibition touches on topics ranging from women’s rights to the multiple iterations of the Arab spring in the Middle East. Sharaf’s work also portrays current events, such as Saudi Arabia’s recent decision to allow women to drive motorcycles and bicycles as long as a male guardian accompanies them. A free public reception and art viewing will be held on Aug. 28 from 5:30 to 8 p.m. at the UNC FedEx Global Education Center. Sponsors: Carolina Center for the Study of the Middle East and Muslim Civilizations, the Center for Global Initiatives, the Duke-UNC Consortium for Middle East Studies and Global Relations with support from the Department of Asian Studies. Special thanks to Andy Berner, communications specialist for the North Carolina Area Health Education Centers (AHEC) Program Thurs, -

The Carroll News- Vol. 89, No. 10

John Carroll University Carroll Collected The aC rroll News Student 12-6-2012 The aC rroll News- Vol. 89, No. 10 John Carroll University Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews Recommended Citation John Carroll University, "The aC rroll News- Vol. 89, No. 10" (2012). The Carroll News. 986. http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews/986 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aC rroll News by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEC Chairman Be a gift-giving Schapiro to step genius this down, p. 13 holiday season, p. 5 THE Thursday,C DecemberARROLL 6, 2012 The Student Voice of John Carroll University N Since 1925 EWSVol. 89, No. 10 The beginning of a new era Former Blue Streak and NFL QB Tom Arth named head football coach Photo courtesy of JCU Sports Information Zach Mentz Arth, who served as an assistant coach, co-offensive co- “I am so proud to represent a university that is commit- Sports Editor ordinator and quarterbacks coach for the football program for ted to leadership, service, academic excellence and, most When Tom Arth graduated from John Carroll University the past three seasons, will replace Regis Scafe as the head importantly, to helping young people realize the God-given in the spring of 2002, he definitely left his mark as one of the coach of JCU’s historic football program, and he couldn’t potential they have to succeed and to make a difference in most talented and accomplished players in the storied history be more excited about the opportunity at hand. -

Stifling Dissent

STIFLING DISSENT HOW ISRAEL’S DEFENDERS USE FALSE CHARGES OF ANTI-SEMITISM TO LIMIT THE DEBATE OVER ISRAEL ON CAMPUS Jewish Voice for Peace Fall 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 STIFLING DISSENT 2 THE STRATEGIES 3 THE PURPOSE OF THIS REPORT 5 OVERVIEW OF THE REPORT: 6 RECOMMENDATIONS: 8 2. BULLYING INSIDE THE JEWISH COMMUNITY 10 2.1 HILLEL’S ISRAEL GUIDELINES 10 2.1.1. BRANDEIS HILLEL REJECTS CAMPUS JEWISH VOICE FOR PEACE CHAPTER – MARCH 2011 11 2.1.2 SUNY BINGHAMTON HILLEL FORCES STUDENT LEADER TO RESIGN – DECEMBER 2012 12 2.1.3 REJECTION OF UCLA-JVP FROM UCLA HILLEL – APRIL 2014 13 2.1.4. SWARTHMORE KEHILAH —MARCH 2015 14 2.2 MARGINALIZATION AND EXCLUSION BEYOND THE HILLEL GUIDELINES 15 2.2.1 UC-BERKELEY’S JEWISH STUDENT UNION REJECTS J STREET U – 2011 AND 2013 15 2.2.2 ATTEMPTS TO CENSOR THE FILM BETWEEN TWO WORLDS AT UCLA AND UCSC, 2011 17 3. STUDENT GOVERNMENT INTERVENTION 19 3.1 TRAINING JEWISH STUDENTS IN ISRAEL ADVOCACY 20 3.1.1 HASBARA FELLOWSHIPS 21 3.1.2 PRO-VIOLENCE PROGRAMS IN ISRAELI SETTLEMENTS 22 3.2. CULTIVATING NON-JEWISH ISRAEL ADVOCATES 22 4. REDEFINING ANTI-SEMITISM TO SILENCE SPEECH 24 4.1 TITLE VI COMPLAINTS 25 4.2 LEGAL THREATS AGAINST ADMINISTRATORS AND FACULTY 28 4.2.1. CONNECTICUT COLLEGE 28 4.2.2 ”WARNING LETTER” TO UNIVERSITIES 29 4.2.3 THREATS OVER CO-SPONSORED EVENTS 29 4.2.4 TARGETING FACULTY DIRECTLY 34 4.3 CODIFYING LIMITATIONS TO FREEDOM OF SPEECH 35 4.3.1 CODIFYING A DEFINITION OF ANTI-SEMITISM 35 4.3.1.1. -

Handful of Salt Volume XXXVIIXXXVII,, Number 111 Januaryjanuary----Februaryfebruary 2013

1 Handful of Salt Volume XXXVIIXXXVII,, Number 111 JanuaryJanuary----FebruaryFebruary 2013 From the drones and weapons kill children and adults in Director’s Pakistan, Gaza, Afghanistan, Yemen. Our bases surround Iran. Chair I want to pull at the threads that make this By Liz tapestry and identify them as carefully as Moore possible. This is just a start and I hope you'll join the conversation at our blog. pulling at One thread is our cultural and political the threads fetishization of weapons and of our 2nd of our Amendment. Arms now are hardly the same culture of thing at all as those around at the time the 2nd violence Amendment was written, which took a minute Like you, my thoughts, heart, and sorrow to manually load for every shot. Now, semi- have been with the families, children, automatic guns pump out rounds. No, the teachers, and entire community of Newtown, problem isn't JUST access to guns, but CT, in the wake of the devastating tragedy of certainly easy access to these massively 28 people, including 20 children, shot and destructive weapons is a tragic thread. killed in Sandy Hook Elementary School. I Another element of this thread is how we have felt the need not to engage with much show weaponry to children, and they clearly media coverage of this heartbreaking event, understand it as a pathway to power. Fig Tree but I do feel the need to share some reflection editor Mary Stamp shared seeing toy assault and thoughts with you here. weapons offered for Christmas gifts in local This horrible atrocity is part of a pattern of stores and suggests one action is to ask stores violence in our country. -

Events at Duke, Events at UNC, Events in the Triangle

Events at Duke, Events at UNC, Events in the Triangle Mon Aug 27, 2012 All day Exhibit: Walking in Quicksand: An Exhibition by Zalmai Mon Aug 27, 2012 - Wed Aug 29, 2012 Where: Art Gallery, First Floor, John Hope Franklin Center Calendar: Events at Duke Created by: Christopher Wallace Description: Zalmai received initial support for Walking in Quicksand from theMagnum Foundation's Emergency Fund in 2011. As the first entry pointinto Europe from the Middle East, Greece receives among the largestnumber of Afghani migrants and asylum seekers in all of Europe. Zalmaitraveled to Greece to expose the deteriorating condition of Afghan migrants trapped in Greece's dysfunctional asylum system. The projectwill be exhibited at Duke University's John Hope Franklin Center forInterdisciplinary and International Studies from August 27th toSeptember 28th as part of the Magnum Foundation and Duke UniversityCenter for International Studies (DUCIS) residency program. Tue Aug 28, 2012 All day Exhibit: Walking in Quicksand: An Exhibition by Zalmai Mon Aug 27, 2012 - Wed Aug 29, 2012 Where: Art Gallery, First Floor, John Hope Franklin Center Calendar: Events at Duke Created by: Christopher Wallace Description: Zalmai received initial support for Walking in Quicksand from theMagnum Foundation's Emergency Fund in 2011. As the first entry pointinto Europe from the Middle East, Greece receives among the largestnumber of Afghani migrants and asylum seekers in all of Europe. Zalmaitraveled to Greece to expose the deteriorating condition of Afghan migrants trapped in Greece's dysfunctional asylum system. The projectwill be exhibited at Duke University's John Hope Franklin Center forInterdisciplinary and International Studies from August 27th toSeptember 28th as part of the Magnum Foundation and Duke UniversityCenter for International Studies (DUCIS) residency program. -

Wetenschappelijke Verhandeling Palestijnse, Israëlische En

UNIVERSITEIT GENT FACULTEIT POLITIEKE EN SOCIALE WETENSCHAPPEN Palestijnse, Israëlische en internationale activisten verenigd in het verzet tegen de muur in de West-Bank Wetenschappelijke verhandeling aantal woorden: 22883 STEFANIE DHONDT MASTERPROEF MANAMA CONFLICT AND DEVELOPMENT PROMOTOR : PROF. DR. CHRISTOPHER PARKER COMMISSARIS : PROF. DR. SAMI ZEMNI COMMISSARIS : LIC. ELS LECOUTERE ACADEMIEJAAR 2009 - 2010 2 Inzagerecht in de masterproef (*) Ondergetekende, ……………………………………………………. geeft hierbij toelating / geen toelating (**) aan derden, niet- behorend tot de examencommissie, om zijn/haar (**) proefschrift in te zien. Datum en handtekening ………………………….. …………………………. Deze toelating geeft aan derden tevens het recht om delen uit de scriptie/ masterproef te reproduceren of te citeren, uiteraard mits correcte bronvermelding. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- (*) Deze ondertekende toelating wordt in zoveel exemplaren opgemaakt als het aantal exemplaren van de scriptie/masterproef die moet worden ingediend. Het blad moet ingebonden worden samen met de scriptie onmiddellijk na de kaft. (**) schrappen wat niet past ________________________________________________________________________________________ 3 4 Abstract Aan het Palestijnse verzet tegen de muur dat plaatsvindt in verschillende dorpen in de West-Bank, nemen wekelijks een grote groep Israëlische en internationale activisten deel. De constructie van de muur creëerde een plaats waar Palestijnse, Israëlische en internationale activisten -

Violent Repression of Palestinian Anti-Wall Protests

1 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 METHODOLOGY 8 INTRODUCTION & PURPOSE OF THE PAPER 10 CHAPTER 1: THE POPULAR RESISTANCE MOVEMENT AGAINST THE APARTHEID WALL 16 The organizational structures against the Wall 17 June 2002 to October 2003: The rising of the popular resistance against the 18 Wall November 2003 to November 2005: The resistance against the Wall 19 intensifies November 2005 to May 2008: The resistance against the Wall has the reorganize itself 21 May 2008 to July 2009: Popular resistance to the Wall: a dangerous 23 phenomenon CHAPTER 2: VIOLENT REPRESSION OF PALESTINIAN ANTI- WALL PROTESTS 26 2.1 THREATS AS THE BASIS OF POLICY 28 2.1.1 Threats of physical violence against individuals or groups 28 2.1.2 Threats of violence against property 30 2.2 TARGETING INDIVIDUALS 31 2.2.1 Violent repression 31 2.2.2 Overwhelming aggression 32 2.2.3 Targeting individuals for serious, lasting injury 32 2.2.4 Killings 36 2.2.5 Punitive attacks outside of demonstrations 38 2.3 COLLECTIVE PUNISHMENT OF VILLAGES 40 2.3.1 Night terror raids 40 2.3.2 Curfew, closure and siege 41 2.3.3 Intentional tear-gassing of homes 42 2.3.4 Destruction of property 43 2.4 INTENT AND AIMS OF REPRESSION 44 2.4.1 Proving intent 2.4.2 Explaining purpose 46 2.4.3 The double game 47 2.4.4 Criteria of racist discrimination in the use of violence 49 2.5 COLLECTIVE PUNISHMENT: BLACKMAILING OF THE COMMUNITY 50 2.6 THE RATIONALE OF REPRESSION 51 2 CHAPTER 3: VIOLATIONG CIVIL AND POLITICAL RIGHTS – ARRESTS AND DETENTION OF COMMUNITIES AND SUPPORTERS INVOLVED IN PROTESTS -

Curriculum Student Trip September 2012

CURRICULUM STUDENT TRIP SEPTEMBER 2012 Disclaimer: Sensitivity to cultural and religious practice and observance is a strong value of OTI. Any religious sites or events listed on the curriculum are meant for educational purposes only. All participants (students, faculty, staff) are provided opportunities to observe their own religious practices during the trip, including but not limited to prayer service (e.g. Friday prayers); consumption or avoidance of specific foods; observance of Sabbath or other holidays. Monday - September 3rd: Flight to Washington DC • 6:03 am Leave LAX • 1:56 pm Arrival in Washington Dulles (IAD) • 3:00 pm Pick-up from Airport by bus, drive to Washington DC • 4:00 pm Check in Hotel (Sheraton Pentagon City, Washington D.C.) • 5:45 pm Leave with taxis to MLK memorial • 6:00 pm TOUR of Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial with UCI Vice-Chancellor for Student Affairs Thomas Parham • 7:00 pm Dinner with Adriel Borshansky and Student Leaders of Seeds of Peace Tuesday – September 4th: Washington DC • 9:30 am MEETING at the Hotel with Jeff Helsing (Dean of Curriculum, United States Institute of Peace) • 11:00 am MEETING with Robert Malley (Former Senior White House Advisor) at the International Crisis Group offices • 12:30 pm LUNCH with experts David Makovsky (the Ziegler distinguished fellow and director of the Washington Institute for the Near East Policy on the Middle East Peace Project) and Ghaith Al-Omari (American Task Force for Palestine) at HOTEL • 2:30 pm Meeting with Retired Ambassador Dennis Ross (Former Middle East Negotiator) at HOTEL • 4:00 pm MEETING with US State Department Special Representative to Muslim Communities Farah Pandith, and Special Envoy to Monitor and Combat Anti-Semitism Hannah Rosenthal about 2011 Hours Against Hate Campaign at Department of State. -

The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem

Applied Research Institute - Jerusalem (ARIJ) P.O Box 860, Caritas Street – Bethlehem, Phone: (+972) 2 2741889, Fax: (+972) 2 2776966. [email protected] | http://www.arij.org Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Report on the Israeli Colonization Activities in the occupied State of Palestine Volume 11, January 2018 Issue http://www.arij.org Bethlehem • The Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) detained a Palestinian, identified as Muhammad Ali Ibrahim Taqatqa, 25, from Beit Fajjar village south 3 of Bethlhem city after raiding hid family house and searching it. (WAFA 12 January 2018) • The Israeli occupation Army (IOA) invaded Beit Fajjar town, south of Bethlehem, confiscated eight cars, and posted warnings leaflets, threatening further invasions should protests continue. (IMEMC 3 January 2018) • In Bethlehem, the Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) detained Ma’ali Issa Ma’ali, and shot ten Palestinians, in Deheishe refugee camp, south of the city. (IMEMC 4 January 2018) • Dozens of Israeli soldiers, and undercover officers, invaded the Deheishe refugee camp in Bethlehem, and initiated violent searches of homes. The soldiers fired many live rounds, rubber-coated steel bullets and gas bombs, wounding ten Palestinians, including four with live fire. The soldiers also invaded and violently searched many homes in the refugee camp, and detained Ma’ali Issa Ma’ali, 34. (IMEMC 4 January 2018) • The Israeli occupation Army (IOA) accompanied by a bulldozer and a large cargo tanker, confiscated a mobile caravan in Shoshala village in the town of al-Khader south of Bethlehem, belonging to Mustafa Abu 1 Applied Research Institute - Jerusalem (ARIJ) P.O Box 860, Caritas Street – Bethlehem, Phone: (+972) 2 2741889, Fax: (+972) 2 2776966. -

Palestinian Popular Struggle and Civil Resistance Theory

Unarmed and Participatory: Palestinian Popular Struggle and Civil Resistance Theory by Michael J. Carpenter M.A., University of Regina, 2008 B.A., University of Regina, 2003 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Political Science © Michael J. Carpenter, 2017 University of Victoria This dissertation is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution -NonCommercial- ShareAlike 4.0 Unported Copyright Supervisory Committee Unarmed and Participatory: Palestinian Popular Struggle and Civil Resistance Theory by Michael J. Carpenter M.A., University of Regina, 2008 B.A., University of Regina, 2003 Supervisory Committee Dr. Scott Watson, Department of Political Science, University of Victoria Supervisor Dr. James Tully, Department of Political Science, University of Victoria Departmental Member Dr. Martin Bunton, Department of History, University of Victoria Outside Member ii Abstract Dr. Scott Watson, Department of Political Science, University of Victoria Supervisor Dr. James Tully, Department of Political Science, University of Victoria Departmental Member Dr. Martin Bunton, Department of History, University of Victoria Outside Member This dissertation advances the literature on civil resistance by proposing an alternative way of thinking about action and organization, and by contributing a new case study of Palestinian struggle in the occupied West Bank. Civil resistance, also known as civil disobedience, nonviolent action, and people power, is about challenging -

The Israeli Colonization Activities in the Occupied Palestinian Territory During the Fourth Quarter of 2017

Applied Research Institute - Jerusalem (ARIJ) & Land Research Center – Jerusalem (LRC) [email protected] | http://www.arij.org [email protected] | http://www.lrcj.org The Israeli Colonization Activities in the occupied Palestinian Territory during the Fourth Quarter of 2017 (October – December)/2017 The Quarterly report highlights the This presentation is prepared as part of chronology of events concerning the the project entitled “Addressing the Israeli Violations in the West Bank and the Geopolitical Changes in the Occupied Gaza Strip, the confiscation and razing of Palestinian Territory”, which is financially lands, the uprooting and destruction of fruit supported by the EU and SDC. However, trees, the expansion of settlements and the contents of this presentation are the erection of outposts, the brutality of the sole responsibility of ARIJ and do not Israeli Occupation Army, the Israeli settlers necessarily reflect those of the donors violence against Palestinian civilians and properties, the erection of checkpoints, the construction of the Israeli segregation wall and the issuance of military orders for the various Israeli purposes. 1 Applied Research Institute - Jerusalem (ARIJ) & Land Research Center – Jerusalem (LRC) [email protected] | http://www.arij.org [email protected] | http://www.lrcj.org Map 1: The Israeli Segregation Plan in the occupied Palestinian Territory 2 Applied Research Institute - Jerusalem (ARIJ) & Land Research Center – Jerusalem (LRC) [email protected] | http://www.arij.org [email protected] | http://www.lrcj.org Bethlehem Governorate - (October 2017 - December 2017) Israeli Violations in Bethlehem Governorate during the Month of October 2017 An Israeli raid in Doha south of Bethlehem city erupted into clashes and a house in the town caught fire.