JTCP-2009-Vol1n1 P53 Walchester

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Owl and the Pussy-Cat the Owl and the Pussy-Cat Went

The Owl and the Pussy-Cat The Owl and the Pussy-Cat went to sea In a beautiful pea-green boat, They took some honey, and plenty of money, Wrapped up in a five pound-note. The Owl looked up to the stars above, And sang to a small guitar, 'O lovely Pussy! O Pussy, my love, What a beautiful Pussy you are, You are, You are! What a beautiful Pussy you are.' Pussy said to the Owl, 'You elegant fowl, How charmingly sweet you sing. O let us be married, too long have we tarried, But what shall we do for a ring?' They sailed away for a year and a day, To the land where the Bong-tree grows, And there in the wood a Piggy-wig stood, With a ring in the end of his nose, His nose, His nose! With a ring in the end of his nose. 'Dear Pig, are you willing, to sell for one shilling Your ring?' Said the Piggy, 'I will.' So they took it away, and were married next day, By the Turkey who lives on the hill. They dined on mince, and slices of quince, Which they ate with a runcible spoon; And hand in hand, on the edge of the sand, They danced by the light of the moon, The moon, The moon, They danced by the light of the moon. Edward Lear (1812-1888) 15 Gramercy Park New York, NY 10003 (212) 254-9628 / www.poetrysociety.org Sympathy I know what the caged bird feels, alas! When the sun is bright on the upland slopes; When the wind stirs soft through the springing grass, And the river flows like a stream of glass; When the first bird sings and the first bud opens, And the faint perfume from its chalice steals— I know what the caged bird feels! I know why the caged -

Edward Lear's Lines of Flight

Journal of the British Academy, 1, 31–69. DOI 10.5871/jba/001.031 Posted 18 July 2013. © The British Academy 2013 Edward Lear’s lines of flight Chatterton Lecture on Poetry read 1 November 2012 by MATTHEW BEVIS Abstract: ‘Verily I am an odd bird’, Edward Lear wrote in his diary in 1860. This article examines a range of odd encounters between birds and people in Lear’s paint ings, illustrations, and poems. It considers how his interest in birds—an interest at once scientific and aesthetic—helped to shape his nonsense writings. I suggest that poetic and pictorial lines of flight became, for Lear, a means of exploring the claims that art might make on our attention. Keywords: Edward Lear, poetry, painting, flight, birds, Charles Darwin, nonsense, evolution, Alfred Tennyson. until now I never knew That fluttering things have so distinct a shade. Wallace Stevens, ‘Le Monocle de Mon Oncle’ (1918) ‘If you cannot tell me how the shadows of the blessed jackdaws will fall I don’t know what I shall do’, wrote Edward Lear to William Holman Hunt in 1852.1 The poet’s feeling for the life of things was often enhanced by his regard for their fleeting effects. ‘Myriads of pigeons!’, he later exclaimed, ‘And when they fly, their shadows on the ground!’2 Notwithstanding the lessons of Plato’s cave, shadows, for Lear, inhabit the realm of the knowable; they are not simply a mistake, or a deception, or a diversion from the real. At once copies and reanimations, shadows may also stand as an analogue for art. -

'Saved from the Sordid Axe': Representation and Understanding

1 ‘Saved from the sordid axe’: representation and understanding of pine trees by English visitors to Italy in the eighteenth and nineteenth century Pietro Piana, Charles Watkins and Ross Balzaretti Abstract Pine trees were frequently depicted and celebrated by nineteenth century English artists and travellers in Italy. The amateur artist and connoisseur Sir George Beaumont was horrified to discover in 1821 that many Roman stone pines were being felled and paid a landowner to preserve a prominent tree on Monte Mario. William Wordsworth saw this tree in 1837 and celebrated that it had been ‘Saved from the sordid axe by Beaumont's care’. Pines continued to be painted by amateurs and professionals including Elizabeth Fanshawe, William Strangways, Edward Lear, John Ruskin. These trees were also an important element of local agriculture; in parts of Liguria they were grown in vineyards in an unusual type of coltura promiscua providing both support for the vines and fertiliser from pine needles; in Tuscany and Ravenna pine plantations and forests were an important source of pine nuts. In this paper we combine the analysis of local land management records, paintings and traveller’s accounts to reclaim differing understandings of the role of the pine in nineteenth century Italy. Introduction: Sir George Beaumont, Wordsworth and the pines of Rome With the final defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo in June 1815 Italy, especially Rome, once again became a favourite destination for British cultural tourists (Buzard, 1993, Liversidge and Edwards, 1996, Black, -

The History of Children's Illustration and Literature Has Always Offered

MARCELLA TERRUSI CHILD PORTRAITS. REPRESENTATIONS OF THE CHILD BODY IN CHILDREN’S ILLUSTRATION AND LITERATURE: SOME INTERPRETATIVE CATEGORIES RITRATTI DI BAMBINO. RAPPRESENTAZIONI DEL CORPO INFANTILE NELLE ILLUSTRAZIONI E NELLA LETTERATURA PER BAMBINI: ALCUNE CATEGORIE INTERPRETATIVE A critical path in the history of children’s illustration and literature, discovering the portraits and metaphors of childhood that attract the scholar’s attention to pedagogical thought on the imagination, and some ideas for interpreting representations of the child body. Un percorso critico nella storia della letteratura e delle illustrazioni per bambini, alla scoperta dei ritratti e delle metafore di infanzia che hanno attratto l’attenzione degli studiosi per un pensiero pe- dagogico sull’immaginazione e di alcune idee per interpretare le rappresentazioni dei corpi infantili. Key words: history of children’s literature, history of illustration, metaphors of childhood, collective imagi- nation, body. Parole chiave: storia della letteratura dell’infanzia, storia delle illustrazioni, metafore dell’infanzia, imma- ginazione collettiva, corpo. The history of children’s illustration and literature has always offered images of childhood in which different children’s figures emerge from the folds of the story with the strength of a visual representation that gives scholars different eyes for interpret- ing the underlying symbolic universe. The rich heritage found in the best works of children’s illustrated literature offers an ideal opportunity for deciphering the depth of childhood metaphors. Children’s literature, or invisible literature (Beseghi e Grilli 2011) while increasingly less invisible as new contributions enrich its critical study, invites us to observe the children’s world in all its intricate details, in the figures that render its fundamental “otherness” (Bernardi 2016) compared to the adult world, in all its complexity and wealth. -

Edward Lear - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Edward Lear - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Edward Lear(12 May 1812 – 29 January 1888) Edward Lear was an English artist, illustrator, author, and poet, renowned today primarily for his literary nonsense, in poetry and prose, and especially his limericks, a form that he popularised. <b>Biography</b> Lear was born into a middle-class family in the village of Holloway, the 21st child of Ann and Jeremiah Lear. He was raised by his eldest sister, also named Ann, 21 years his senior. Ann doted on Lear and continued to mother him until her death, when Lear was almost 50 years of age. Due to the family's failing financial fortune, at age four he and his sister had to leave the family home and set up house together. Lear suffered from health problems. From the age of six he suffered frequent grand mal epileptic seizures, and bronchitis, asthma, and in later life, partial blindness. Lear experienced his first seizure at a fair near Highgate with his father. The event scared and embarrassed him. Lear felt lifelong guilt and shame for his epileptic condition. His adult diaries indicate that he always sensed the onset of a seizure in time to remove himself from public view. How Lear was able to anticipate them is not known, but many people with epilepsy report a ringing in their ears (tinnitus) or an aura before the onset of a seizure. In Lear's time epilepsy was believed to be associated with demonic possession, which contributed to his feelings of guilt and loneliness. -

APPENDIX ALCOTT, Louisa May

APPENDIX ALCOTT, Louisa May. American. Born in Germantown, Pennsylvania, 29 November 1832; daughter of the philosopher Amos Bronson Alcott. Educated at home, with instruction from Thoreau, Emerson, and Theodore Parker. Teacher; army nurse during the Civil War; seamstress; domestic servant. Edited the children's magazine Merry's Museum in the 1860's. Died 6 March 1888. PUBLICATIONS FOR CHILDREN Fiction Flower Fables. Boston, Briggs, 1855. The Rose Family: A Fairy Tale. Boston, Redpath, 1864. Morning-Glories and Other Stories, illustrated by Elizabeth Greene. New York, Carleton, 1867. Three Proverb Stories. Boston. Loring, 1868. Kitty's Class Day. Boston, Loring, 1868. Aunt Kipp. Boston, Loring, 1868. Psyche's Art. Boston, Loring, 1868. Little Women; or, Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy, illustrated by Mary Alcott. Boston. Roberts. 2 vols., 1868-69; as Little Women and Good Wives, London, Sampson Low, 2 vols .. 1871. An Old-Fashioned Girl. Boston, Roberts, and London, Sampson Low, 1870. Will's Wonder Book. Boston, Fuller, 1870. Little Men: Life at Pluff?field with Jo 's Boys. Boston, Roberts, and London. Sampson Low, 1871. Aunt Jo's Scrap-Bag: My Boys, Shawl-Straps, Cupid and Chow-Chow, My Girls, Jimmy's Cruise in the Pinafore, An Old-Fashioned Thanksgiving. Boston. Roberts. and London, Sampson Low, 6 vols., 1872-82. Eight Cousins; or, The Aunt-Hill. Boston, Roberts, and London, Sampson Low. 1875. Rose in Bloom: A Sequel to "Eight Cousins." Boston, Roberts, 1876. Under the Lilacs. London, Sampson Low, 1877; Boston, Roberts, 1878. Meadow Blossoms. New York, Crowell, 1879. Water Cresses. New York, Crowell, 1879. Jack and Jill: A Village Story. -

Edward Lear Works in Public Collections and in Other Collections Open to the Public

Edward Lear works in Public Collections and in other collections open to the public The purpose of this document is to give as complete a record as possible of Edward Lear’s works which are in public collections around the world and also those in institutions where researchers should be able to access them with permission. There are around 5000 such landscape drawings and many more finished watercolours and oil paintings. It would be a difficult task to list them all. So the method used has been to show, by each collection, the numbers of drawings, finished watercolours and oils, and in almost all cases the countries he depicted and in the case of drawings the year of travel. Section 1 lists Lear’s travels in chronological order. Section 2 provides the listing by collection. To use the document search facility (this pdf uses Adobe), go to Edit > Find, or to Edit > Advanced Search. Find will create a Find box on the screen. Type in a word and click Next. The first time that word appears should be highlighted in the text. Continue clicking Next to find progressively all its appearances in the document first in Section 1 and then in Section 2. Advanced Search will create a menu column on the left of the screen. Enter the word required and Search, and a drop down menu of all the word’s appearances should appear. These are not very helpful in themselves, but as each is highlighted, the same word will be highlighted in the document. It is only possible to search for single or consecutive words or dates. -

L'italia Nei Limerick

How to reference this article Tarnogórska, M. (2020). L’Italia nei limerick. Italica Wratislaviensia, 11(2), 163–188. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15804/IW.2020.11.2.9 Maria Tarnogórska Uniwersytet Wrocławski, Polonia [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0001-5257-1620 L’ITALIA NEI LIMERICK ITALY IN LIMERICKS Abstract: This article presents the comic images of Italy that transpire from Italy’s representation in the English- and Polish-language limerick. In accordance with the rules of the genre, Italy becomes a stage for nonsense characters and actions. The outlined literary motifs of Italy, a country normally connoting high civilisation and a historically rich culture, studied in Polish- and English-language authors, confirm the sophisticated nature of the genre, popular in intelligentsia circles. The article focuses on the following four areas: 1. the pioneering role of Edward Lear’s A Book of Nonsense (1846), which, for the first time in limerick form, features names of Italian localities as well as the ‘Italian’ experiences of Lear himself, a landscape painter and English expatriate who was not only enchanted by Italy but was also a sensitive observer of the alien human ‘habitat’ created by locally cherished customs; 2. a humorously conceived ‘map’ of Italy to be crafted on the basis of representative collections and anthologies of limericks; 3. historical figures—especially those connected with the proud history of the Roman Empire, whose limerick image is far removed from its official textbook biographies; 4. the presence of contemporary Italian language (associated with musicality and elegance) and classical Latin (associated with high education) in the limerick narration, contrasting with the frequently bawdy content of the verse, which is a source of humour. -

Viaggio Attraverso L'abruzzo Pittoresco

Viaggiatori stranieri in terra d’Abruzzo Oggetto: Edward Lear Cronologia: 1846 Opera: Viaggio Attraverso l’Abruzzo pittoresco Autore: Edwar Lear nacque ad Halloway, nei pressi di Londra, nel 1812, fu scrittore e pittore. Spesso illustrava le sue stesse opere. Ebbe un’ adolescenza difficile, venti fratelli e un padre in prigione per debiti, e la vita turbata sin dalla giovinezza dalla malattia: soffriva infatti di epilessia e di asma. Abile disegnatore a diciotto anni insegnava privatamente e realizzava incisioni e stampe. Per mantenersi eseguì una serie di disegni o schizzi a carattere zoologico per la Reale Società Zoologica e pubblico nel 1832 il suo primo album “Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae”. In seguito fu ospite e dipendente del Conte di Derby, come pittore naturalista, dove scrisse i suoi limerick per divertire i figli del conte e nel 1846 pubblica “Book of Nonsense”. Edward Lear passò gran parte della sua vita a viaggiare (grazie al lavoro, che gli permette di visitare luoghi più salubri), legandosi in particolar modo all'Italia: nel 1837 fu a Roma, da lì viaggiò molto nel meridione. Durante tutti i suoi viaggi produsse numerosi resoconti illustrati e nel 1841 pubblicò “Illustrated Excursions in Italy”, “Journal of a Landscape Painter in Southern Calabria”. Quattro anni di lavoro gli permettono di raccogliere i suoi limerick (brevi componimenti poetici) corredati di illustrazioni nel celeberrimo libro “A Book of Nonsense” che pubblica nel 1846 dietro lo pseudonimo di Derry Down Derry. Lear si dilettò a scrivere di botanica o alfabeti nonsense, che riunì nel libro “Nonsense Songs”, “Stories” e in “Botany and Alphabets”inverno. -

Lear and Fantasy Script

Edward Lear fantasy podcast script 1. Title page Welcome to this short introduction to Edward Lear and Fantasy. Edward Lear was born in North London in 1812 and died in Northwestern Italy in 1888. Lear was a popular Victorian artist, illustrator, musician, author and poet. He’s most well known today as the father of English ‘nonsense’, and is especially famed for his limericks, a form he popularised. 2. Lear’s books His hugely popular books included A Book of Nonsense, Nonsense Songs and Stories, More Nonsense, Laughable Lyrics, Nonsense Alphabets, and Nonsense Botany, all variously published between 1846 and the end of his life. 3. Fantasy vs Nonsense When thinking about Lear and fantasy as a genre, it feels important to consider the difference between the terms ‘fantastical’ and ‘nonsensical’. - fantastical = ‘imaginative or fanciful; remote from reality’; - nonsensical = ‘having no meaning; making no sense’, ridiculously impractical or ill-advised’ That is to say, Lear’s writing is fantastical, which makes him a fantasy writer, but his work’s strong sense of the ridiculous and satirical also makes him a nonsense writer. The same might be said of Lewis Carroll, whose works often seek above all to entertain. According to Stephen Prickett, Victorian fantasy flourished in opposition to the repressive social and intellectual conditions of 'Victorianism'. Victorian writers such as Lear, Lewis Carroll, Charles Kingsley and George MacDonald all used non-realistic techniques such as nonsense, dreams, visions, and the creation of other worlds to extend our understanding of this world and to question and escape from the ideology of Victorian culture and society. -

The Natural History of Edward Lear

The natural history of Edward Lear The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation McCracken Peck, Robert. 2012. The natural history of Edward Lear. Harvard Library Bulletin 22 (2-3). 1-68. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37363352 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Te Natural History of Edward Lear Robert McCracken Peck lthough he is best remembered today as a whimsical nonsense poet, adventurous traveler, and painter of luminous landscapes, Edward Lear Ais revered in scientifc circles as one of the greatest natural history painters of all time. During his relatively brief immersion in the world of science, he created a spectacular monograph on parrots and a body of other work that continues to inform, delight, and astonish us with its remarkable blend of scientifc rigor and artistic fnesse. Tanks to the generosity of two discerning Harvard benefactors, Philip Hofer and William B. Osgood Field, Houghton Library holds the largest and most complete collection of Edward Lear’s original paintings in the world. Among the more than 4,000 items in this collection are some 200 sketches, studies, and fnished paintings devoted to parrots and other subjects of natural history. From April to August 2012 the Library will be exhibiting a representative sample of this work to commemorate the bicentennial of Lear’s birth. -

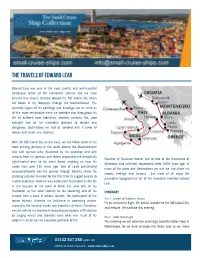

The Travels of Edward Lear

THE TRAVELS OF EDWARD LEAR Edward Lear was one of the most prolific and well-travelled landscape artists of the nineteenth century and we have devised this unique itinerary aboard the MS Island Sky which will follow in his footsteps through the Mediterranean. The splendid legacy of his paintings and drawings can be seen as all the more remarkable when we consider that throughout his life he suffered from bronchitis, monthly epileptic fits, poor eyesight and on his numerous journeys to remote and dangerous destinations he had to contend with a terror of horses and severe sea-sickness. With the MS Island Sky as our base, we will follow some of his most exciting journeys in the lands around the Mediterranean Sea with special talks illustrated by his paintings and with extracts from his journals and letters (especially the delightfully Quarries of Syracuse forever tied to fate of the thousands of light-hearted ones to his sister Anne) enabling us hear his Athenians who perished, imprisoned there 2500 years ago. In words from over 120 years ago. One of Lears outstanding many of the ports and destinations we visit we can share his accomplishments was his journey through Albania where his moods, feelings and humour - but most of all enjoy the stunning pictures revealed for the first time its rugged beauty to perceptive topographical art of the incredibly talented Edward a wide audience. There he was particularly fascinated by the life Lear. in the bazaars of the town of Berat but also tells of his frustration at the local hostility to his sketching and of his ITINERARY escape from a pack of odious hounds.