Cultural Identity, Hybridity and Minority Media: Community Access Radio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethnic Migrant Media Forum 2014 | Curated Proceedings 1 FOREWORD

Ethnic Migrant Media Forum 2014 CURATED PROCEEDINGS “Are we reaching all New Zealanders?” Exploring the Role, Benefits, Challenges & Potential of Ethnic Media in New Zealand Edited by Evangelia Papoutsaki & Elena Kolesova with Laura Stephenson Ethnic Migrant Media Forum 2014. Curated Proceedings is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Ethnic Migrant Media Forum, Unitec Institute of Technology Thursday 13 November, 8.45am–5.45pm Unitec Marae, Carrington Road, Mt Albert Auckland, New Zealand The Introduction and Discussion sections were blind peer-reviewed by a minimum of two referees. The content of this publication comprises mostly the proceedings of a publicly held forum. They reflect the participants’ opinions, and their inclusion in this publication does not necessarily constitute endorsement by the editors, ePress or Unitec Institute of Technology. This publication may be cited as: Papoutsaki, E. & Kolesova, E. (Eds.) (2017). Ethnic migrant media forum 2014. Curated proceedings. Auckland, New Zealand. Retrieved from http://unitec. ac.nz/epress/ Cover design by Louise Saunders Curated proceedings design and editing by ePress Editors: Evangelia Papoutsaki and Elena Kolesova with Laura Stephenson Photographers: Munawwar Naqvi and Ching-Ting Fu Contact [email protected] www.unitec.ac.nz/epress Unitec Institute of Technology Private Bag 92025, Victoria Street West Auckland 1142 New Zealand ISBN 978-1-927214-20-6 Marcus Williams, Dean of Research and Enterprise (Unitec) opens the forum -

TSB COMMUNITY TRUST REPORT 2016 SPREAD FINAL.Indd

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 CHAIR’S REPORT Tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou katoa Greetings, greetings, greetings to you all The past 12 months have been highly ac ve for the Trust, As part of the Trust’s evolu on, on 1 April 2015, a new Group marked by signifi cant strategic developments, opera onal asset structure was introduced, to sustain and grow the improvements, and the strengthening of our asset base. Trust’s assets for future genera ons. This provides the Trust All laying stronger founda ons to support the success of with a diversifi ca on of assets, and in future years, access to Taranaki, now and in the future. greater dividends. This year the Trust adopted a new Strategic Overview, As well as all this strategic ac vity this year we have including a new Vision: con nued our community funding and investment, and To be a champion of posi ve opportuni es and an agent of have made a strong commitment to the success of Taranaki benefi cial change for Taranaki and its people now and in communi es, with $8,672,374 paid out towards a broad the future range of ac vi es, with a further $2,640,143 commi ed and yet to be paid. Our new Vision will guide the Trust as we ac vely work with others to champion posi ve opportuni es and benefi cial Since 1988 the Trust has contributed over $107.9 million change in the region. Moving forward the Trust’s strategic dollars, a level of funding possible due to the con nued priority will be Child and Youth Wellbeing, with a focus on success of the TSB Bank Ltd. -

WHERE ARE the EXTRA ANALYSIS September 2020

WHERE ARE THE AUDIENCES? EXTRA ANALYSIS September 2020 Summary of the net daily reach of the main TV broadcasters on air and online in 2020 Daily reach 2020 – net reach of TV broadcasters. All New Zealanders 15+ • Net daily reach of TVNZ: 56% – Includes TVNZ 1, TVNZ 2, DUKE, TVNZ OnDemand • Net daily reach of Mediaworks : 25% – Includes Three, 3NOW • Net daily reach of SKY TV: 22% – Includes all SKY channels and SKY Ondemand Glasshouse Consulting June 20 2 The difference in the time each generation dedicate to different media each day is vast. 60+ year olds spend an average of nearly four hours watching TV and nearly 2½ hours listening to the radio each day. Conversely 15-39 year olds spend nearly 2½ hours watching SVOD, nearly two hours a day watching online video or listening to streamed music and nearly 1½ hours online gaming. Time spent consuming media 2020 – average minutes per day. Three generations of New Zealanders Q: Between (TIME PERIOD) about how long did you do (activity) for? 61 TV Total 143 229 110 Online Video 56 21 46 Radio 70 145 139 SVOD Total 99 32 120 Music Stream 46 12 84 Online Gaming 46 31 30 NZ On Demand 37 15-39s 26 15 40-59s Music 14 11 60+ year olds 10 Online NZ Radio 27 11 16 Note: in this chart average total minutes are based on a ll New Zealanders Podcast 6 and includes those who did not do each activity (i.e. zero minutes). 3 Media are ranked in order of daily reach among all New Zealanders. -

Pacific Media Forum 2012

Pacific Media Forum 2012 A small forum of Pacific broadcasting leaders met on 19 July 2012 at the Pacific Media Network in Manukau. The purpose was to discuss the research paper commissioned by NZ On Air - Broadcast Programming for Pacific Audiences released in June 2012, and to think about ways that broadcasting services to Pacific people in New Zealand could be improved. Given the difficult economic climate significant new Government funding is unlikely to be available for some time. Suggested improvements were considered within the context of NZ On Air’s legislative remit. The document is a brief overview of the discussion and feedback from the forum. Discussion about the research: The general view was that it was a valuable piece of research. The desires of the Pacific communities expressed in the surveys were not a surprise to most attendees. Some gaps in the research were identified: o The Survey Monkey research probably did not reach audiences over age 35. This is the main demographic listening to Pacific language radio. o The television survey did not include new youth series Fresh. o Did not establish if there is a gap in the range of Pacific voices in narrative and drama. o It would be helpful to know which Pacific projects have been funded and who are the Pacific production companies. o The internet is a very important platform for Pacific youth and some felt it was not adequately covered in the research. o Others thought that the ‘digital divide’ is not as much of a barrier for Pacific audiences as was expressed in the research. -

2018 RBA Annual Report

2 018 RADIO BROADCASTERS ASSOCIATION ANNUAL REPORT www.rba.co.nz THE YEAR BY NUMBERS NUMBER OF PEOPLE EMPLOYED BY RBA COMMERCIAL STATIONS – IN THE REGION OF 1,800 ANNUAL RADIO REVENUE $ 279.4 MILLION % OF ALL NZ ADVERTISING REVENUE 10.63% # OF COMMERCIAL RADIO FREQUENCIES– 103 AM & 678 FM 781 # OF LISTENERS AGED 10+ TO ALL RADIO AS AT S4 DECEMBER 2018 84% OF ALL NEW ZEALANDERS* 3.59 MILLION # OF LISTENERS AGED 10+ TO COMMERCIAL RADIO AS AT S4 DECEMBER 2018 78% OF ALL NEW ZEALANDERS* 3.32 MILLION # OF RADIO STUDENTS IN 2018 With almost 3.6 million people listening to radio each week and 3.3 million of those listening to commercial radio, we are one 173 of, if not the most used media channels every week in New Zealand. We need to shout this loudly and proudly. Jana Rangooni, RBA CEO www.rba.co.nz FROM THE RBA CHAIRMAN, FROM THE RBA CEO, NORM COLLISON JANA RANGOONI 2018 was a challenging As I write our support of a thriving mainstream year for all organisations in this report music industry in New Zealand. the media throughout New I, like so • We have revised the radio agency Zealand as we faced more many in the accreditation scheme and increased competition at a global level. industry, the number of agencies participating. It was pleasing therefore to are still see radio yet again hold its grieving • We have developed a new plan own in terms of audiences the loss with Civil Defence to engage with and advertising revenue. of our the 16 CDEM regions to ensure the Memorandum of Understanding with We ended the year with over 3.3 million New Zealanders colleague Darryl Paton who so many MCDEM is activated across New listening to commercial radio each week and $279.4 million in know from his years at The Edge and The Zealand. -

1 Rethinking Journalism and Culture

1 RETHINKING JOURNALISM AND CULTURE: AN EXAMINATION OF HOW PACIFIC AUDIENCES EVALUATE ETHNIC MEDIA Journalism Studies Tara Ross Media and Communication Department School of Language, Social and Political Sciences University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand [email protected] http://www.arts.canterbury.ac.nz/media/people/ross.shtml Funding This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. 2 RETHINKING JOURNALISM AND CULTURE: AN EXAMINATION OF HOW PACIFIC AUDIENCES EVALUATE ETHNIC MEDIA Studies of indigenous and ethnic minority news media tend to emphasise their political advocacy role, their role in providing a voice to communities overlooked by mainstream media and, increasingly, the cultural forces at work in these media. By considering ethnic media in terms of how ethnic minority audiences understand what they do with these media, this study provides a different perspective. Focus groups held with Pacific audiences at several urban centres in New Zealand found participants routinely use the idea of journalism in evaluating Pacific media – and journalism for them was a term defined to a significant extent by wider societal expectations around journalism, and not by their ethnic difference. Through examining the intersection of media practices with the ideals and expectations of journalism, this paper questions how far we should foreground the specifics of culture in interpreting people’s media use, and advocates a commitment to more empirical research to reorient the study of ethnic media away from a fixation on difference and towards people’s media practices. KEYWORDS: culture; ethnic media; journalism; media practices; Pacific audiences This paper studies audience members of Pacific ethnic media in terms of how they value the news they receive from ethnic media sources. -

2015 TDHB Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2014-15 Taranaki Together, a Healthy Community Taranaki Whanui, He Rohe Oranga OUR AIMS A Matou Wawata ɶ To promote healthy lifestyles and self responsibility ɶ To have the people and infrastructure to meet changing health needs ɶ To have people as healthy as they can be through promotion, prevention, early intervention and rehabilitation ɶ To have services that are people-centred and accessible, where the health sector works as one ɶ To have a multi-agency approach to health ɶ To improve the health of Māori and groups with poor health status ɶ To lead and support the health and disability sector and provide stability throughout change ɶ To make the best use of the resources available Registered Office Banker Advisors Auditors Taranaki District Health Board TSB Bank Govett Quilliam Office of the Controller 27 David Street 120 Devon Street East Private Bag 2013 and Auditor-General New Plymouth 4310 New Plymouth 4310 New Plymouth 4342 Agent - Deloitte Telephone: + 64 (6) 753 6139 PO Box 17 Facsimile + 64 (6) 753 7770 Westpac Hamilton 3240 Email: [email protected] Po Box 8141 Website: www.tdhb.org.nz New Plymouth 4310 2 Our Shared Vision / Te Matakite Taranaki Together, a Healthy Community Taranaki Whanui, He Rohe Oranga HOW WE WORK TOGETHER AND CONTENTS Our Aims .......................................... 2 WITH OTHERS (NGA TIKANGA) Introduction by Chairman and Chief Executive .......................... 4 Me Pehea nga mahi ngatahi me etehi atu Taranaki Health Foundation ............ 6 On Target........................................ 10 The actions and behaviours described below are how we aim to Where the Money Goes ................ -

Horror Five Days Push up Road Toll Opunake Again Has a Three Deaths in fi Ve Days More Than for All of 2015

Vol. 25 No 15, August 12, 2016 www.opunakecoastalnews.co.nz Published every Thursday Fortnight Phone and Fax 761-7016 A/H 761-8206 for Advertising and Editorial ISSN 2324-2337, ISSN 2324-2345 Inside Himalayan trip to help rebuild earthquake damaged schools founded by mountaineering excited as the departure day great Sir Edmund Hillary. looks closer. They fi rstly fl y As many as 33 schools to Kathmandu, where the were destroyed in the May, money raised will be handed 2015 earthquakes. Many over to the Himalayan people lost their lives - an Trust in Kathmandu. Old style house wins estimated 6000 or so. The Next, they will take a New House Award. need to rebuild is urgent as flight to Lukua, a town Page 7 so many Nepalese children in the Himalayas. From are without adequate there, a 20 to 25 day hike schooling at present. to Everest Base camp will Harrison’s school Rahotu follow, with three mountain Primary has got behind the passes to be negotiated. fundraising venture. Some They expect the whole of the events scheduled trip to take about 30 days. include a Sausage Sizzle If you’d like to help you on Friday August 26, can support the various starting around midday. events planned at Rahotu Celebrating our next Another event at the school School and Opunake rugby stars. Page 19 is planned for Tuesday Kindergarten. You can September 20, which will be also contribute by sending a Mufti Day combined with money to the BNZ account another Sausage Sizzle. 02 0256 0031716 001. -

Community Funding Investment Committee (11 August 2020) - Agenda

Community Funding Investment Committee (11 August 2020) - Agenda MEETING AGENDA COMMUNITY FUNDING INVESTMENT COMMITTEE Tuesday, 11 August 2020 at 9.30am COUNCIL CHAMBER LIARDET STREET NEW PLYMOUTH Chairperson: Cr Amanda Clinton-Gohdes Members: Cr Tony Bedford Cr Gordon Brown Cr Anneka Carlson Cr Harry Duynhoven Cr Dinnie Moeahu Mayor Neil Holdom 1 Community Funding Investment Committee (11 August 2020) - Health and Safety Health and Safety Message In the event of an emergency, please follow the instructions of Council staff. Please exit through the main entrance. Once you reach the footpath please turn right and walk towards Pukekura Park, congregating outside the Spark building. Please do not block the foothpath for other users. Staff will guide you to an alternative route if necessary. If there is an earthquake – drop, cover and hold where possible. Please be mindful of the glass overhead. Please remain where you are until further instruction is given. 2 Community Funding Investment Committee (11 August 2020) - Apologies APOLOGIES None advised. 3 Community Funding Investment Committee (11 August 2020) - Deputations ADDRESSING THE MEETING Requests for public forum and deputations need to be made at least one day prior to the meeting. The Chairperson has authority to approve or decline public comments and deputations in line with the standing order requirements. PUBLIC FORUM Public Forums enable members of the public to bring matters to the attention of the committee which are not contained on the meeting agenda. The matters must relate to the meeting’s terms of reference. Speakers can speak for up to 5 minutes, with no more than two speakers on behalf of one organisation. -

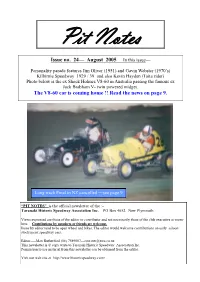

August 2005 in This Issue— the V8-60 Car Is Coming Home

Pit Notes Issue no. 24— August 2005 In this issue— Personality parade features Jim Oliver (1951) and Gavin Webster (1970’s) Kilbirnie Speedway 1929 / 39 and also Kevin Hayden (Taita rider) Photo below is the ex Shock Holmes V8-60 in Australia passing the famous ex Jack Brabham V- twin powered midget. The V8-60 car is coming home !! Read the news on page 9. Long track Final in NZ cancelled —see page 9 “PIT NOTES” is the official newsletter of the :- Taranaki Historic Speedway Association Inc. PO Box 4052, New Plymouth Views expressed are those of the editor or contributor and not necessarily those of the club executive or mem- bers. Contributions by members or friends are welcome. Items by editor tend to be open wheel and bikes. The editor would welcome contributions on early saloon/ stock/sprint speedway cars. Editor—–Max Rutherford (06) 7589007—[email protected] This newsletter is © copy write to Taranaki Historic Speedway Association Inc. Permission to use material from this newsletter can be obtained from the editor. Visit our web site at http://www.historicspeedway.co.nz P-2 Officers of the ass., Presidents report.— President, Laurie Callender Our August meeting was very well attended and the new venue and Tuesday evening 06-762 4012 hm. appears to very popular. It was great to see so many new faces and hear the speedway [email protected] stories and many “wins” these people had. This is what our club is all about. Vice President and Historian. Our speaker for the night was Lew Martin who spoke on his involvement at Wai- Dave Gifford 758 8941 hm. -

Reaching the Community Through Community Radio

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UC Research Repository REACHING THE COMMUNITY THROUGH COMMUNITY RADIO Readjusting to the New Realities A Case Study Investigating the Changing Nature of Community Access and Participation in Three Community Radio Stations in Three Countries New Zealand, Nepal and Sri Lanka __________________________________________________________________________ A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Ahmed Zaki Nafiz University of Canterbury 2012 _____________________________________________________________________________ Dedicated to my beloved parents: Abdulla Nafiz and Rasheeda Mohammed Didi i ABSTRACT Community radio is often described as a medium that celebrates the small community life and where local community members plan, produce and present their own programmes. However, many believe that the radio management policies are now increasingly sidelining this aspect of the radio. This is ironic given the fact that the radio stations are supposed to be community platforms where members converge to celebrate their community life and discuss issues of mutual interest. In this case study, I have studied three community radio stations- RS in Nepal, KCR in Sri Lanka and SCR in New Zealand- investigating how the radio management policies are positively or negatively, affecting community access and participation. The study shows that in their effort to stay economically sustainable, the three stations are gradually evolving as a ‘hybrid’; something that sits in-between community and commercial radio. Consequently, programmes that are produced by the local community are often replaced by programmes that are produced by full-time paid staff; and they are more entertaining in nature and accommodate more advertisements. -

Vamping the Archive: Approaching Aesthetics in Global Media

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Center for Advanced Research in Global CARGC Papers Communication (CARGC) Spring 2018 Vamping the Archive: Approaching Aesthetics in Global Media Rayya El Zein University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/cargc_papers Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation El Zein, Rayya, "Vamping the Archive: Approaching Aesthetics in Global Media" (2018). CARGC Papers. 8. https://repository.upenn.edu/cargc_papers/8 CARGC Paper 8 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/cargc_papers/8 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vamping the Archive: Approaching Aesthetics in Global Media Description CARGC Paper 8, “Vamping the Archive: Approaching Aesthetics in Global Media,” by CARGC Postdoctoral Fellow, Rayya El Zein, is based on El Zein’s CARGC Colloquium and draws its inspiration from Metro al- Madina's Hishik Bishik Show in Beirut. CARGC Paper 8 weaves assessments of local and regional contexts, aesthetic and performance theory, thick description, participant observation, and interview to develop an approach to aesthetics in cultural production from the vantage of global media studies that she calls “vamping the archive.” Disciplines Communication Comments CARGC Paper 8 Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This report is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/cargc_papers/8 CARGC PAPER 8 Vamping the Archive: Approaching 2018 Aesthetics in Global Media Yasmina Fayyed sings “Sona, oh Sonson,” in the Hishik Bishik Show. Photo by @foodartconcept, August 16, 2016. Vamping the Archive: Approaching Aesthetics in Global Media CARGC PAPER 8 2018 I am very proud to share CARGC been fully explored and that we feel Paper 8, “Vamping the Archive: are important for the development of Approaching Aesthetics in Glob- global media studies.