'God Is Not a Christian'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix Table 4: List of Experts in the Field Contacted Name Affiliation

Appendix Table 4: List of experts in the field contacted Name Affiliation Abbey Hatcher University of California at San Francisco, USA Adeline Nyamathie University of California, Los Angeles, USA Alison Wringe London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK Amin Hasub-Saharan African KEMRI/Wellcome Trust Centre for Geographic Medicine Research, KE Amy Corneli University of North Carolina, USA Andrew Boulle University of Cape Town, SA Andrew Edmonds University of North Carolina, USA Anju Seth Lady Hardinge Medical College and Associated Kalawati Saran Children's Hospital, IN Annette Sohn TREAT Asia, TH Barbara Amuron Uganda Research Unit on AIDS, UG Basia Zaba London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK Bruce Larson Boston University, USA,/Health Economics and Epidemiology Research Office, SA Carol Metcalf Médecins Sans Frontières, SA Catherine Sutcliffe Johns Hopkins University, USA Catrina Mugglin University of Bern, CH Christian Unge Karolinska Institutet, SE Dam Tran University of New South Wales, AU David Vlahov New York Academy of Medicine, USA Deborah Watson Jones London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK Degu Jereene World Health Organization, ET Denis Nash Columbia University, USA Dominique Pepper University of Cape Town, SA Dunstan Haule Pastoral Activities and Services for people with AIDS Dar es Salaam Archdiocese , TZ Edward Mills University of Ottawa, USA Elena Losina Masub-Saharan Africachusetts General Hospital, USA Elizabeth Lowenthal Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, USA Elvin Geng University of California, -

A Toolkit for Teachers and Schools 2Nd Edition PREFACE

GENDER RESPONSIVE PEDAGOGY A TOOLKIT FOR TEACHERS AND SCHOOLS 2ND EDITION PREFACE The quality of teaching across all levels of education has a significant impact on academic access, retention and performance of girls and boys in Africa. This includes the systematic professionalization of both teaching and non-teaching roles within education, by improving teacher training and support for teachers. Notably, many teachers in sub-Saharan Africa, conditioned by patriarchal values in their communities, employ teaching methods that are not conducive for equal participation of both girls and boys. Neither do these methods take into account the individual needs of learners, especially girls. Equipping teachers with knowledge, skills and attitudes to enable them to respond adequately to the learning needs of girls and boys through using gen- der-aware classroom processes and practices ultimately improves learning outcomes and enhances gender sensitivity in the delivery of education services. The Forum for African Women Educationalists (FAWE) in 2005 developed the Gender-Responsive Pedagogy (GRP) model to address the quality of teaching in African schools. The GRP model trains teachers to be more gender aware and equips them with the skills to understand and address the specific learning needs of both sexes. It develops teaching practices that engender equal treatment and participation of girls and boys in the classroom and in the wider school community. It advocates for classroom practices that ensure equal par- ticipation of girls and boys, including a classroom environment that encourages both to thrive. Teachers are trained in the design and use of gender-responsive lesson plans, classroom interaction, classroom set-up, language use in the classroom, teaching and learning materials, management of sexual maturation, strategies to eliminate sexual harassment, gender-responsive school management systems, and monitoring and eval- uation. -

Tutu in Memory, Tutu on Memory Strategies of Remembering Tinyiko Maluleke1

Missionalia 47-2 Maluleke(177–192) 177 www.missionalia.journals.ac.za | https://doi.org10.7832/47-2-342 Tutu in Memory, Tutu on Memory Strategies of Remembering Tinyiko Maluleke1 Abstract This essay profiles the strategies and (theological) tactics used by Desmond Tutu in the management of painful memory in his own personal life, in his various leader- ship roles in church and society as well as in his role as chairperson of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission. To contextualise Tutu’s work, we refer, amongst others, to the work of Elie Wiesel, Don Mattera and Leonard Cohen. The essay provides a profile of the ways in which Tutu is remembered as well as the approaches Tutu himself uses in his own acts of remembering. The latter include the importance of childhood memories, the anchoring of memory in familial and paren- tal relationships, a keen awareness of the socio-economic conditions, the valorisa- tion of childhood church experiences, the privileging of the Bible, the leveraging of Ubuntu, making forgiveness the main lens through which to look into the past as well as the maintenance of a hermeneutic that suggests that God is historically on the side of the weak.2 1. Memory as Weapon In the conclusion to his memoire on the Apartheid-era destruction of Sophiatown and the brutal removal of its black inhabitants, Don Mattera paints a picture of a township that was left “buried deep under the weight and power of the tin gods whose bulldozers” decimated hopes and dreams, leaving in their wake, the “dust of defeat”. -

THE COLOMBIA CHARTER – 10 Principles for Peace –

THE COLOMBIA CHARTER – 10 principles for Peace – Without ideals and values, human conduct lacks a compass 1. PEACE IS A RIGHT: Peace is the birthright of every individual and the supreme right of humanity. 2. WE ARE ONE: Humanity is one family, sharing the gift of life together on this fragile planet. What happens to one of us, it happens to all of us. 3. WE ARE DIVERSE: Our humanity is enriched by diversity. This is a treasure that we all must honor and take care of. 4. WE HAVE TO FOLLOW THE GOLDEN RULE: The moral principle of treating others as one wants to be treated must be applied not only to the personal conduct but also to the conduct of religions and nations. 5. WE MUST AVOID WAR: War shreds the fabric of human community and represents failures of our humanity. 6. WE MUST BE LEGAL AND JUST: World peace and stability require adherence to and respect for International Law, including International Human Rights Law and International Humanitarian Law. Lasting peace can only be achieved if it is based on social justice. 7. WE SHOULD TALK: Whenever it is possible, conflicts should be ended through dialogue. The international community has to validate effective measures to prevent and limit wars. PERMANENT SECRETARIAT OF THE WORLD SUMMIT OF NOBEL PEACE LAUREATES Tel.: +39 06 56566159 Fax: +39 06 92942573 [email protected] - www.nobelpeacesummit.org 8. WE HAVE TO RESPECT EACH OTHER: Even in conflict, an enemy must be recognized as a human being entitled to respect, and their motivations must be understood. -

Desmond Tutu: a Theological Model for Justice in the Context of Apartheid Tracy Riggle Denison University

Denison Journal of Religion Volume 7 Article 4 2007 Desmond Tutu: A Theological Model for Justice in the Context of Apartheid Tracy Riggle Denison University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/religion Part of the Ethics in Religion Commons, and the Sociology of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Riggle, Tracy (2007) "Desmond Tutu: A Theological Model for Justice in the Context of Apartheid," Denison Journal of Religion: Vol. 7 , Article 4. Available at: http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/religion/vol7/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Denison Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denison Journal of Religion by an authorized editor of Denison Digital Commons. Riggle: Desmond Tutu: A Theological Model for Justice in the Context of A DESMOND M. TUTU: Theological MODEL FOR JUSTICE IN THE CONTEXT Apartheid Desmond M. Tutu: Theological Model for Justice in the Context of Apartheid Tracy Riggle n our current age of modernity, the role religion can play in transforming the world is certainly highly debated. There are those people who relegate Ireligion to a sphere of unimportance, deeming it a study only applicable to antiquity. There are others, however, who insist upon the continuing validity and importance of religion. The question around which this work will focus is what kind of impact religion can have on our modern world of injustice. The goal of this research is to highlight religion’s propensity to be what Lloyd Steffen refers to as “life affirming” (Steffen 5). Religion which is life affirming acts as an alterna- tive to a demonic religion which promotes violence and injustice by valuing the lives of certain individuals over others. -

Your Decision on the Keystone XL Tar Sands Pipeline Will Define Your Climate Legacy

Your decision on the Keystone XL tar sands pipeline will define your climate legacy. As Nobel Laureates, we call on you to do the right thing and reject this pipeline. Dear President Obama & Secretary Kerry, You are among the first generation of leaders that knows better — leaders that have the knowledge, tools, and opportunity to pivot our societies away from fossil fuels and towards smarter, safer and cleaner energy. History will You stand on the brink of making a reflect on this moment and it will be clear to our children and grandchildren choice that will define your legacy on if you made the right choice. one of the greatest challenges humanity As we have said in our previous letters, we have found hope in your words and promises to work to ensure a safer climate. We continue to be has ever faced — climate change. inspired by the millions of people who have made this an intergenerational As you deliberate the Keystone XL tar sands pipeline, you are poised to movement of climate defenders with a goal of holding you accountable make a decision that will signal either a dangerous commitment to the to these words. As recipients of the Nobel Peace Prize, we feel we have status quo, or bold leadership that will inspire millions counting on you to a moral obligation to raise our voices in support and solidarity for those do the right thing for our shared climate. We stand with the 2,000,000 across North America and the world that are fighting not only for impacted voices who submitted their comments in the national interest determination people and communities today, but for the generations to come that will process rejecting the pipeline and ask you once again to stop Keystone XL. -

International Activity Report 2019 the Médecins Sans Frontières Charter

INTERNATIONAL ACTIVITY REPORT 2019 www.msf.org THE MÉDECINS SANS FRONTIÈRES CHARTER Médecins Sans Frontières is a private international association. The association is made up mainly of doctors and health sector workers, and is also open to all other professions which might help in achieving its aims. All of its members agree to honour the following principles: Médecins Sans Frontières provides assistance to populations in distress, to victims of natural or man-made disasters and to victims of armed conflict. They do so irrespective of race, religion, creed or political convictions. Médecins Sans Frontières observes neutrality and impartiality in the name of universal medical ethics and the right to humanitarian assistance, and claims full and unhindered freedom in the exercise of its functions. Members undertake to respect their professional code of ethics and to maintain complete independence from all political, economic or religious powers. As volunteers, members understand the risks and dangers of the missions they carry out and make no claim for themselves or their assigns for any form of compensation other than that which the association might be able to afford them. The country texts in this report provide descriptive overviews of MSF’s operational activities throughout the world between January and December 2019. Staffing figures represent the total full-time equivalent employees per country across the 12 months, for the purposes of comparisons. Country summaries are representational and, owing to space considerations, may not be comprehensive. For more information on our activities in other languages, please visit one of the websites listed on p. 100. The place names and boundaries used in this report do not reflect any position by MSF on their legal status. -

Ending Corporal Punishment of Children – a Handbook

ENDING CORPORAL Ending corporal punishment of children – A handbook for working with and within religious communities A handbook for working with and within religious – punishment of children Ending corporal PUNISHMENT OF CHILDREN A handbook for working with and within religious communities CNNV Churches’ Network for Non-violence ENDING CORPORAL PUNISHMENT OF CHILDREN ❧ ❧ ❧ A handbook for working with and within religious communities Contents 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................1 a) The links between religion and corporal punishment of children ............................1 b) About the handbook ................................................................................................5 2 Corporal punishment of children – a global problem ......................................9 a) The prevalence of corporal punishment ..................................................................9 b) The impact of corporal punishment .......................................................................12 c) Children’s perspectives .......................................................................................... 14 d) The importance of legal reform ..............................................................................16 e) Progress towards prohibition worldwide ............................................................... 17 3 Children’s right to protection from corporal punishment .............................. 19 a) The Convention on the Rights -

Men & HIV Forum

Men & HIV Forum 20 July 2019 | Fiesta Americana Mexico Toreo, Mexico City, Mexico Lee Abdelfadil – [email protected] Lee Abdelfadil is a Senior HIV Advisor at the Global Fund to Fight HIV, Tuberculosis and Malaria. She is qualified public health specialist with more than 10 years’ national and international experience in HIV and AIDS and TB programme design, management and implementation. Before joining the Global Fund, Lee worked with the International HIV/AIDS Alliance, United Nations Development Programme and the Ministry of Health in Sudan. She is currently pursuing a PhD at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Helen Ayles - [email protected] Helen Ayles is a Professor of Infectious Diseases and International Health in the Clinical Research Department at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and has lived in Zambia for 20 years working at Zambart in Lusaka. Helen’s research interest is in the combined epidemics of TB and HIV and in the evaluation of large public health interventions. She is the Zambia principal investigator for the PopART trial (HPTN071), a large community- randomized trial of treatment as prevention for HIV and the PI of a nested trial of HIV self-testing funded by 3ie. She is an investigator in the STAR initiative of HIV self-testing. Gary Barker – [email protected] Gary Barker, PhD, is a leading global voice in engaging men and boys in advancing gender equality and positive masculinities. He is the CEO and founder of Promundo, which has worked for 20 years in more than 40 countries. -

Christian Story Based on Mark 5:21-34)

PEACE Sick Woman Who Finds Peace (Christian story based on Mark 5:21-34) PREVIEW Review Guidelines Background – Christianity Lesson/Story Modern-Day Healer – Mother Teresa Creative Response – String of Hands Craft Activity #1 – Odds/Evens Finger Game Activity #2 – Finger Spelling Activity #3 – Sign Language Take-Home Opportunity – Peace for the Sick List of Previous Peace-Makers Lessons List of Previous Peace for the World Lessons Images Provided – Desmond Tutu, Mother Teresa REVIEW Review 1-3 stories from the Peace-Makers section – maybe one or two stories about keeping people from fighting and one of the Jesus stories. Then review one or two stories from the Peace for the World section. Then, review both stories from the Finding Your Own Peace section. Don’t let the review get too long. Keep it to five or ten minutes, even though there’s a lot that could potentially be covered. Dhat’s Magical Journey (Sufi): Royal son travelled to distant land to retrieve a precious gem from a monster. After getting distracted, he completed his mission, returned to his kingdom, and realized that true peace could be found “at home.” Wise Boy Refuses to Fight Chief (Sub-Saharan African): A boy, named Wiser-Than-the- Chief, outsmarted the Chief of the land. Rather than getting rid of the boy, the Chief let him and his family live in peace. BACKGROUND – CHRISTIANITY Prompt: Today, we’re going to read another Jesus story found in the Christian Bible. Do you know/ remember where we find the Jesus stories – the back part or the front part of the Christian Bible? [back part] Prompt: The Christian Bible is the sacred text for Christians. -

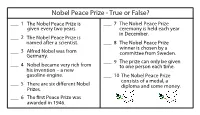

Nobel Peace Prize - True Or False?

Nobel Peace Prize - True or False? ___ 1 T he Nobel Peace Prize is ___ 7 The Nobel Peace Prize given every two years. ceremony is held each year in December. ___ 2 T he Nobel Peace Prize is n amed after a scientist. ___ 8 The Nobel Peace Prize winner is chosen by a ___ 3 A lfred Nobel was from c ommittee from Sweden. G ermany. ___ 9 T he prize can only be given ___ 4 N obel became very rich from t o one person each time. his invention – a new gasoline engine. ___ 10 T he Nobel Peace Prize consists of a medal, a ___ 5 There are six dierent Nobel diploma and some money. Prizes. ___ 6 The rst Peace Prize was awarded in 1946 . Nobel Peace Prize - True or False? ___F 1 T he Nobel Peace Prize is ___T 7 The Nobel Peace Prize given every two years. Every year ceremony is held each year in December. ___T 2 T he Nobel Peace Prize is n amed after a scientist. ___F 8 The Nobel Peace Prize winner is chosen by a Norway ___F 3 A lfred Nobel was from c ommittee from Sweden. G ermany. Sweden ___F 9 T he prize can only be given ___F 4 N obel became very rich from t o one person each time. Two or his invention – a new more gasoline engine. He got rich from ___T 10 T he Nobel Peace Prize dynamite T consists of a medal, a ___ 5 There are six dierent Nobel diploma and some money. -

In the Spirit of Ubuntu: Enforcing the Rights of Orphans and Vulnerable

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship Winter 2008 In the Spirit of Ubuntu: Enforcing the Rights of Orphans and Vulnerable Children Affected by HIV/AIDS in South Africa John Bessler University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Jurisprudence Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation In the Spirit of Ubuntu: Enforcing the Rights of Orphans and Vulnerable Children Affected by HIV/AIDS in South Africa, 31 Hast. Int’l & Comp. L. Rev. 33 (2008) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1745077 In the Spirit of Ubuntu. Enforcing the Rights of Orphans and Vulnerable Children Affected by HIV/AIDS in South Africa ByJOHND. BESSLER' Africans believe in something that is difficult to render in English. We call it ubuntu, botho. It means the essence of being human. You know it when it is there and when it is absent. It speaks about humaneness, gentleness, hospitality, putting yourself out on behalf of others, being vulnerable. It embraces compassion and toughness. It recognizes that my humanity is bound up in yours, for we can only be human together. - Archbishop Desmond Tutu" • Visiting Associate Professor of Law, The George Washington University Law School, Washington, D.C.; Adjunct Professor of Law, University of Minnesota Law School.