United Nations Peacekeepers Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MIRPUR PAPERS, Volume 22, Issue 23, November 2016

ISSN: 1023-6325 MIRPUR PAPERS, Volume 22, Issue 23, November 2016 MIRPUR PAPERS Defence Services Command and Staff College Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka-1216 Bangladesh MIRPUR PAPERS Chief Patron Major General Md Saiful Abedin, BSP, ndc, psc Editorial Board Editor : Group Captain Md Asadul Karim, psc, GD(P) Associate Editors : Wing Commander M Neyamul Kabir, psc, GD(N) (Now Group Captain) : Commander Mahmudul Haque Majumder, (L), psc, BN : Lieutenant Colonel Sohel Hasan, SGP, psc Assistant Editor : Major Gazi Shamsher Ali, AEC Correspondence: The Editor Mirpur Papers Defence Services Command and Staff College Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka – 1216, Bangladesh Telephone: 88-02-8031111 Fax: 88-02-9011450 E-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2006 DSCSC ISSN 1023 – 6325 Published by: Defence Services Command and Staff College Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka – 1216, Bangladesh Printed by: Army Printing Press 168 Zia Colony Dhaka Cantonment, Dhaka-1206, Bangladesh i Message from the Chief Patron I feel extremely honoured to see the publication of ‘Mirpur Papers’ of Issue Number 23, Volume-I of Defence Services Command & Staff College, Mirpur. ‘Mirpur Papers’ bears the testimony of the intellectual outfit of the student officers of Armed Forces of different countries around the globe who all undergo the staff course in this prestigious institution. Besides the student officers, faculty members also share their knowledge and experience on national and international military activities through their writings in ‘Mirpur Papers’. DSCSC, Mirpur is the premium military institution which is designed to develop the professional knowledge and understanding of selected officers of the Armed Forces in order to prepare them for the assumption of increasing responsibility both on staff and command appointment. -

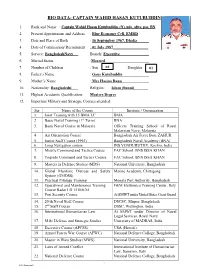

Bio Data- Captain Wahid Hasan Kutubuddin

BIO DATA- CAPTAIN WAHID HASAN KUTUBUDDIN 1. Rank and Name : Captain Wahid Hasan Kutubuddin, (N), ndc, afwc, psc, BN 2. Present Appointment and Address : Blue Economy Cell, EMRD 3. Date and Place of Birth : 16 September 1967, Dhaka 4. Date of Commission/ Recruitment : 01 July 1987__________________ 5. Service: BangladeshNavy Branch: Executive 6. Marital Status :Married 7. Number of Children : Son 02 Daughter 01 8. Father’s Name : Gaus Kutubuddin 9. Mother’s Name : Mrs Hasina Banu 10. Nationality: Bangladeshi Religion: ___Islam (Sunni)_______ 11. Highest Academic Qualification: Masters Degree 12. Important Military and Strategic Courses attended: Ser Name of the Course Institute / Organization 1. Joint Training with 15 BMA LC BMA 2. Basic Naval Training (1st Term) BNA 3. Basic Naval Course in Malaysia Officers Training School of Royal Malaysian Navy, Malaysia 4. Air Orientation Course Bangladesh Air Force Base ZAHUR 5. Junior Staff Course (1992) Bangladesh Naval Academy (BNA) 6. Long Navigation course INS VENDURUTHY, Kochin, India 7. Missile Command and Tactics Course FAC School, BNS ISSA KHAN 8. Torpedo Command and Tactics Course FAC School, BNS ISSA KHAN 9. Masters in Defence Studies (MDS) National University, Bangladesh 10. Global Maritime Distress and Safety Marine Academy, Chittagong System (GMDSS) 11. Practical Pilotage Training Mongla Port Authority, Bangladesh 12. Operational and Maintenance Training GEM Elettronica Training Center, Italy Course Radar LD 1510/6/M 13. Port Security Course At SMWT under United States Coast Guard 14. 20 th Naval Staff Course DSCSC, Mirpur, Bangladesh 15. 2nd Staff Course DSSC, Wellington, India 16. International Humanitarian Law At SMWT under Director of Naval Legal Services, Royal Navy 17. -

Bangladesh-Army-Journal-61St-Issue

With the Compliments of Director Education BANGLADESH ARMY JOURNAL 61ST ISSUE JUNE 2017 Chief Editor Brigadier General Md Abdul Mannan Bhuiyan, SUP Editors Lt Col Mohammad Monjur Morshed, psc, AEC Maj Md Tariqul Islam, AEC All rights reserved by the publisher. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission of the publisher. The opinions expressed in the articles of this publication are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily reflect the policy and views, official or otherwise, of the Army Headquarters. Contents Editorial i GENERATION GAP AND THE MILITARY LEADERSHIP CHALLENGES 1-17 Brigadier General Ihteshamus Samad Choudhury, ndc, psc MECHANIZED INFANTRY – A FUTURE ARM OF BANGLADESH ARMY 18-30 Colonel Md Ziaul Hoque, afwc, psc ATTRITION OR MANEUVER? THE AGE OLD DILEMMA AND OUR FUTURE 31-42 APPROACH Lieutenant Colonel Abu Rubel Md Shahabuddin, afwc, psc, G, Arty COMMAND PHILOSOPHY BENCHMARKING THE PROFESSIONAL COMPETENCY 43-59 FOR COMMANDERS AT BATTALION LEVEL – A PERSPECTIVE OF BANGLADESH ARMY Lieutenant Colonel Mohammad Monir Hossain Patwary, psc, ASC MASTERING THE ART OF NEGOTIATION: A MUST HAVE ATTRIBUTE FOR 60-72 PRESENT DAY’S BANGLADESH ARMY Lieutenant Colonel Md Imrul Mabud, afwc, psc, Arty FUTURE WARFARE TRENDS: PREFERRED TECHNOLOGICAL OUTLOOK FOR 73-83 BANGLADESH ARMY Lieutenant Colonel Mohammad Baker, afwc, psc, Sigs PRECEPTS AND PRACTICES OF TRANSFORMATIONAL LEADERSHIP: 84-93 BANGLADESH ARMY PERSPECTIVE Lieutenant Colonel Mohammed Zaber Hossain, AEC USE OF ELECTRONIC GADGET AND SOCIAL MEDIA: DICHOTOMOUS EFFECT ON 94-113 PROFESSIONAL AND SOCIAL LIFE Major A K M Sadekul Islam, psc, G, Arty Editorial We do express immense pleasure to publish the 61st issue of Bangladesh Army Journal for our valued readers. -

General Studies Series

IAS General Studies Series Current Affairs (Prelims), 2013 by Abhimanu’s IAS Study Group Chandigarh © 2013 Abhimanu Visions (E) Pvt Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system or otherwise, without prior written permission of the owner/ publishers or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act, 1957. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claim for the damages. 2013 EDITION Disclaimer: Information contained in this work has been obtained by Abhimanu Visions from sources believed to be reliable. However neither Abhimanu's nor their author guarantees the accuracy and completeness of any information published herein. Though every effort has been made to avoid any error or omissions in this booklet, in spite of this error may creep in. Any mistake, error or discrepancy noted may be brought in the notice of the publisher, which shall be taken care in the next edition but neither Abhimanu's nor its authors are responsible for it. The owner/publisher reserves the rights to withdraw or amend this publication at any point of time without any notice. TABLE OF CONTENTS PERSONS IN NEWS .............................................................................................................................. 13 NATIONAL AFFAIRS .......................................................................................................................... -

Armed Forces War Course-2013 the Ministers the Hon’Ble Ministers Presented Their Vision

National Defence College, Bangladesh PRODEEP 2013 A PICTORIAL YEAR BOOK NATIONAL DEFENCE COLLEGE MIRPUR CANTONMENT, DHAKA, BANGLADESH Editorial Board of Prodeep Governing Body Meeting Lt Gen Akbar Chief Patron 2 3 Col Shahnoor Lt Col Munir Editor in Chief Associate Editor Maj Mukim Lt Cdr Mahbuba CSO-3 Nazrul Assistant Editor Assistant Editor Assistant Editor Family Photo: Faculty Members-NDC Family Photo: Faculty Members-AFWC Lt Gen Mollah Fazle Akbar Brig Gen Muhammad Shams-ul Huda Commandant CI, AFWC Wg Maj Gen A K M Abdur Rahman R Adm Muhammad Anwarul Islam Col (Now Brig Gen) F M Zahid Hussain Col (Now Brig Gen) Abu Sayed Mohammad Ali 4 SDS (Army) - 1 SDS (Navy) DS (Army) - 1 DS (Army) - 2 5 AVM M Sanaul Huq Brig Gen Mesbah Ul Alam Chowdhury Capt Syed Misbah Uddin Ahmed Gp Capt Javed Tanveer Khan SDS (Air) SDS (Army) -2 (Now CI, AFWC Wg) DS (Navy) DS (Air) Jt Secy (Now Addl Secy) A F M Nurus Safa Chowdhury DG Saquib Ali Lt Col (Now Col) Md Faizur Rahman SDS (Civil) SDS (FA) DS (Army) - 3 Family Photo: Course Members - NDC 2013 Brig Gen Md Zafar Ullah Khan Brig Gen Md Ahsanul Huq Miah Brig Gen Md Shahidul Islam Brig Gen Md Shamsur Rahman Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Brig Gen Md Abdur Razzaque Brig Gen S M Farhad Brig Gen Md Tanveer Iqbal Brig Gen Md Nurul Momen Khan 6 Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army 7 Brig Gen Ataul Hakim Sarwar Hasan Brig Gen Md Faruque-Ul-Haque Brig Gen Shah Sagirul Islam Brig Gen Shameem Ahmed Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh -

Third-Text-120-.Pdf

CTTE 27_1 Cover_CTTE 27_1 Cover 05/01/13 12:43 PM Page 1 THIRD TEXT THIRD TEXT NUMBER 120 JANUARY 2013 THIRD TEXT VOLUME 27 120 ISSUE 1 CRITICAL PERSPECTIVES ON CONTEMPORARY ART & CULTURE JANUARY 2013 NUMBER 120 VOLUME 27 ISSUE 1 JANUARY 2013 27 ISSUE 1 JANUARY NUMBER 120 VOLUME SPECIAL ISSUE: CONTEMPORARY ART AND THE POLITICS OF ECOLOGY GUEST EDITOR: TJ DEMOS CONTEMPORARY ART AND THE POLITICS OF ECOLOGY: AN INTRODUCTION TJ Demos POST-MEDIA ACTIVISM, SOCIAL ECOLOGY AND ECO-ART Christoph Brunner, Roberto Nigro and Gerald Raunig BEYOND THE MIRROR: INDIGENOUS ECOLOGIES AND ‘NEW MATERIALISMS’ IN CONTEMPORARY ART Jessica L Horton and Janet Catherine Berlo AGAINST INTERNATIONALISM Jimmie Durham OUGHT WE NOT TO ESTABLISH ‘ACCESS TO FOOD’: AS A SPECIES RIGHT? Subhankar Banerjee ENTANGLED EARTH Nabil Ahmed ACTIVISM ROOTED IN TRADITION: ARTISTIC STRATEGIES FOR RAISING ENVIRONMENTAL AWARENESS IN ANATOLIA Berin Golonu ENVIRONMENTAL CHALLENGES AND ECO-AESTHETICS IN NIGERIA’S NIGER DELTA Basil Sunday Nnamdi, Obari Gomba and Frank Ugiomoh FROM SUPPLY LINES TO RESOURCE ECOLOGIES World of Matter DELICACY AND DANGER Patrick D Flores THREE AND A HALF CONVERSATIONS WITH AN ECCENTRIC PLANET Raqs Media Collective AFTER HANS HAACKE: TUE GREENFORT AND ECO-INSTITUTIONAL CRITIQUE Luke Skrebowski PLANETARY DYSPHORIA Emily Apter ART, ECOLOGY AND INSTITUTIONS: A CONVERSATION WITH ARTISTS AND CURATORS Steven Lam, Gabi Ngcobo, Jack Persekian, Nato Thompson, Anne Sophie Witzke and Liberate Tate THE ART AND POLITICS OF ECOLOGY IN INDIA: A ROUNDTABLE WITH RAVI AGARWAL -

Unclaimed Deposit Statement for Bank's Website-As on 31.12.2020

SL Name of Branch Present Address Permanent Address Account Type Name of Account/ Beneficiary Account/Instrument No. Father's Name Amount BB Cheque Amount Date of Transfer Remarks No. 1 SKB Branch Law Chamber, Amin Court, 5th Floor, 62-63 Motijheel C/A, Dhaka. NA Current Account Graham John Walker 0003-0210001547 NA 130,569.00 130,569.00 18-Aug-14 2 SKB Branch NA NA NA Grafic System Pvt. Ltd. PAA00014522 NA 775.00 3 SKB Branch NA NA NA Elesta Security Services Ltd. PAA00015444 NA 4,807.00 5,582.00 22-Nov-15 4 SKB Branch 369,New North Goran Khilgaon,Dhaka. Vill-Maziara, PO-Jibongonj Bazar, Nabinagar, Brahman Baria Savings Account Farida Iqbal 0003-0310010964 Khondokar Iqbal Hossain 1,212.00 5 SKB Branch Dosalaha Villa, Sec#6,Block#D,Road#9, House# 11,Mirpur ,Dhaka. Vill-Balurchar, PO-Baksha Nagar,PS-Nababgonj,Dist-Dhaka. Savings Account Md. Shah Alam 0003-0310009190 Late Abdur Razzak 975.00 6 SKB Branch H#26(2nd floor)Road# 111,Block-F,Banani,Dhaka. Vill- Chota Khatmari,PO-Joymonirhat, PS-Bhurungamari,Dist-Kurigram. Savings Account S.M. Babul Akhter 0003-0310014077 Md. Amjad Hossain 782.00 7 SKB Branch 135/1,1st Floor Malibag,Dhaka. Vill-Bhairabdi,PO-Sultanshady,PS-Araihazar,Dist-Narayangonj. Savings Account Mohammad Mogibur Rahman 0003-0310012622 Md. Abdur Rashid 416.00 14,951.00 6-Jun-16 8 SKB Branch A-1/16,Sonali Bank Colony, Motijheel,Dhaka. 12/2,Nabin Chanra Goshwari Road, Shampur, Dhaka. Savings Account Salina Akter Banu 0003-0310012668 Md. Rahmat Ali 966.00 9 SKB Branch Cosmos Center 69/1,New Circular Road,Malibage,Dhaka. -

In the Supreme Court of Bangladesh High Court Division (Special Original Jurisdiction)

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF BANGLADESH HIGH COURT DIVISION (SPECIAL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION) WRIT PETITION NO. 891 OF 1994 In the matter of: An application under Article 102(1) and (2) of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. - And - In the matter of: Dr. Mohiuddin Farooque, Secretary General, Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers Association (BELA) being dead Ms. Syeda Rizwana Hasan, Director (Program), representing Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers Association (BELA).... Petitioner - Versus - Bangladesh and others ...... Respondents. Ms. Syeda Rizwana Hasan with Mr. Md. Iqbal Kabir, Advocate ... For the Petitioner Mr. Md. Zahirul Islam Mukul, A.A.G. ... For the Respondents. Heard on: The 17th & 25th June & 15th July, 2001 Judgment on: The 15th July, 2001. Present: Mr. Justice Md. Joynul Abedin And Mr. Justice A.B.M. Khairul Haque. A.B.M. Khairul Haque, J: 1) This rule was issued at the instance of late Dr. Mohiuddin Farooque, the then Secretary General of Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers Association (BELA for short) an association registered under the Societies Registration Act, 1860, bearing registration No. 1457(17) dated 18-2-1992. Dr. Farooque, by a resolution of the execution committee of BELA dated 30-5-1994, was authorized to represent the said association, to move the High Court Division of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh, under Article 102 of the Constitution of Bangladesh, praying for appropriate relief relating to the matter of control of pollution from industries/factories situated up and down the country. 2) BELA has been registered as an association under the Societies Registration Act, 1860, with the aims and objects, inter alia, to organize and undertake legal of administrative actions and measures to protect, preserve, conserve or reinstate environmental and ecological systems, to protect environmentally sensitive and fragile eco-systems including protection of vulnerable groups, to protect biological diversity, to take measures on environmental or ecological issues regarding development activities. -

160 Pacific Avenue, Suite 200, San Francisco, California 94111 Telephone: 415.249.5800 Fax: 415.772.9137 Website

Carta abierta de los galardonados de Premio Ambiental Goldman a los gobiernos en la ocasión de la Cumbre de la Tierra 2012 Somos los recipientes del Premio Ambiental Goldman. Nos han amenazado. Nos han torturado. Nos han capturado. Hemos muerto por los tóxicos industriales en nuestra sangre. Nos han matado. Somos los recipientes del Premio Ambiental Goldman. Somos de 81 países. Somos activistas locales. Somos embajadores nacionales. Somos pueblos indígenas. Somos ministros del medioambiente. Somos mujeres. Somos hombres. Somos ancianos. Somos jóvenes. Por más de dos décadas el Premio Goldman nos ha honrado, por los grandes riesgos que hemos tomado para proteger el medioambiente. Ahora les pedimos a ustedes arriesgarse. Es su deber participar en la "Cumbre de la Tierra" en Rio de Janeiro y conducirnos a la acción en defensa de la biodiversidad. La Cumbre de la Tierra nos presenta una oportunidad profunda para fortalecer nuestro compromiso global por la protección del planeta, el cual fue reconocido hace 20 años en la histórica "Cumbre de la Tierra Río‐1992". Desde entonces, los pueblos del Mundo han preservado especies en peligro de extinción, conservado territorios frágiles, y desarrollado alternativas para algunos de nuestras practicas más destructivas. Repetidas veces las comunidades han ganado grandes batallas. Pero es la sociedad civil quien esta liderando las acciones de conservación, con gente como nosotros poniendo nuestras vidas y bienestar en peligro por el hecho de proteger el medioambiente. Ahora, urgentemente, les rogamos tomar el liderazgo para proteger el planeta que compartimos, para bien de las futuras generaciones, les impulsamos participar en la Cumbre de la Tierra para hacer compromisos serios hacia el desarrollo sustentable. -

In the Supreme Court of Bangladesh Appellate Division

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF BANGLADESH APPELLATE DIVISION PRESENT: Mr. Justice Md. Muzammel Hossain. -Chief Justice. Mr. Justice Surendra Kumar Sinha Ms. Justice Nazmun Ara Sultana. Mr. Justice Syed Mahmud Hossain. Mr. Justice Muhammad Imman Ali. Mr. Justice Md. Shamsul Huda. CIVIL APPEAL NO.256 OF 2009 with CIVIL APPEAL NOS.253-255 OF 2009. and CIVIL PETITION FOR LEAVE TO APPEAL NO.1689 OF 2006. (From the judgment and order dated 27.07.2005 passed by the High Court Division in Writ Petition No.4604 of 2004 with Writ Petition No.5103 of 2003) Metro Makers and Developers Limited. : Appellant. (In C.A. No.256/09) Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers’ Appellant. Association (BELA). (In C.A. No.253/09) Anser Uddin Ahmed and others. : Appellant. (In C.A. No.254/09)) Managing Director, Metro Makers and : Appellant. Developers Limited. (In C. A. No.255/09) Rajdhani Unnyan Kartipakka (RAJUK). : Petitioner. (In C. P. No.1689/06) -Versus- Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers’ : Respondents Association Limited (BELA) and others. (In C. A Nos.256-254/09) Managing Director, Metro Makers and : Respondents. Developers Limited and others. (In C. A. No.253/09) The Chairman, Rajdhani Unnyan : Respondents. Kartipakka (RAJUK) and others. (In C. A. No.255/09) Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers : Respondents. Association, represented by its Director, (In C. P. No.1689/06) Syeda Rizwana Hasan and others. For the Appellant. : Mr. Ajmalul Hussain, Q.C., Senior (In C. A. No.256/09) Advocate, instructed by Mr. Mvi. Md. 2 Wahidullah, Advocate-on-Record. For the Appellant. : Mr. Mahmudul Islam, Senior (In C. A. -

A Professional Journal of National Defence College Volume 16

A Professional Journal of National Defence College Volume 16 Number 1 June 2017 National Defence College Bangladesh EDITORIAL BOARD Chief Patron Lieutenant General Chowdhury Hasan Sarwardy, BB, SBP, BSP, ndc, psc, PhD Editor-in-Chief Air Vice Marshal M Sanaul Huq, GUP, ndc, psc, GD(P) Editor Colonel A K M Fazlur Rahman, afwc, psc Associate Editors Group Captain Md Mustafizur Rahman, GUP, afwc, psc, GD(P) Lieutenant Colonel A N M Foyezur Rahman, psc, Engrs Assistant Editors Lecturer Farhana Binte Aziz Assistant Director Md Nazrul Islam ISSN: 1683-8475 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electrical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Published by the National Defence College, Bangladesh Design & Printed by : ORNATE CARE 87, Mariam Villah (2nd floor), Nayapaltan, Dhaka-1000, Bangladesh Cell: 01911546613, E mail: [email protected] DISCLAIMER The analysis, opinions and conclusions expressed or implied in this Journal are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NDC, Bangladesh Armed Forces or any other agencies of Bangladesh Government. Statement, fact or opinion appearing in NDC Journal are solely those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by the editors or publisher. III CONTENTS Page College Governing Body vi Vision, Mission and Objectives of the College vii Foreword viii Editorial ix Faculty and Staff x Abstracts xi Population of Bangladesh: Impact -

WOMEN, ENVIRONMENT and ENVIRONMENTAL ADVOCACY: CHALLENGES for BANGLADESH Farzana Nasrin Public Administration Department, Chittagong University, BANGLADESH

ISSN: 2186-8492, ISSN: 2186-8484 Print ASIAN JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES & HUMANITIES Vol. 1. No. 3. August 2012 WOMEN, ENVIRONMENT AND ENVIRONMENTAL ADVOCACY: CHALLENGES FOR BANGLADESH Farzana Nasrin Public Administration Department, Chittagong University, BANGLADESH. ABSTRACT The women’s issues in Bangladesh are considered to be a chronic problem of patriarchal society. Despite several positive policies and programs undertaken by the government and NGOs recently, the position of women in the society did not improve to a satisfactory level. Now, the relationship between women and the environment has become more explicit and apparent. As such, the article seeks to provide basic information related to women and environment and advocacy for environment and women in Bangladesh. Through an extensive review of literatures, this study attempts to shed light on the challenges of women with a view of exploring the linkages between women and environment and adverse impact that falls on women. It also emphasizes on environmental advocacy for women. The work is accomplished on the basis of secondary sources including – book reviews, newspapers, journals, research reports and other secondary materials. Implications of the past literature with regard to empower women as they interact with environmental and cultural elements. Keywords: Bangladesh, environment, patriarchal society, women INTRODUCTION Although half of the world's population is women, only ten percent of global income is spent on them and share less than one percent of global resources (Kholiquzzaman, 1986). They are the poorest of the poor. A recent study on poverty (Rahman et at., 1992) reveals that in Bangladesh, poverty is increasingly feminized. Violence against women is widespread.