Between Organised Crime and Terrorism: Illicit Firearms Actors And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Everyday Intolerance- Racist and Xenophic Violence in Italy

Italy H U M A N Everyday Intolerance R I G H T S Racist and Xenophobic Violence in Italy WATCH Everyday Intolerance Racist and Xenophobic Violence in Italy Copyright © 2011 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-746-9 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org March 2011 ISBN: 1-56432-746-9 Everyday Intolerance Racist and Xenophobic Violence in Italy I. Summary ...................................................................................................................... 1 Key Recommendations to the Italian Government ............................................................ 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................... 4 II. Background ................................................................................................................. 5 The Scale of the Problem ................................................................................................. 9 The Impact of the Media ............................................................................................... -

Ciro Cirillo - Wikipedia

11/5/2020 Ciro Cirillo - Wikipedia Ciro Cirillo Da Wikipedia, l'enciclopedia libera. Ciro Cirillo (Napoli, 15 febbraio 1921 – Torre del Greco, 30 Ciro Cirillo luglio 2017) è stato un politico italiano. Presidente della Regione Campania Indice Durata mandato 1979 – 1980 Biografia Predecessore Gaspare Russo Le origini e la carriera politica Successore Emilio De Feo Il rapimento e liberazione Le dichiarazioni postume Presidente della Provincia di Napoli Letteratura e cinema Durata mandato 1969 – Note 1975 Voci correlate Predecessore Antonio Gava Altri progetti Successore Franco Iacono Biografia Dati generali Partito politico Democrazia Cristiana Le origini e la carriera politica Impiegato alla camera di commercio, industria, artigianato e agricoltura a Napoli, fu un esponente della corrente di Antonio Gava della Democrazia Cristiana e negli anni sessanta ricoprì a lungo la carica di segretario provinciale del partito. Nel 1969 divenne Presidente della Provincia di Napoli e restò in carica fino al 1975[1]. Eletto successivamente Presidente della Regione Campania nel 1979, nel 1981 è assessore regionale ai lavori pubblici nella stessa regione. Dopo il terremoto dell'Irpinia del 1980, Cirillo diventò vicepresidente del Comitato tecnico per la ricostruzione[2]. Il rapimento e liberazione Il 27 aprile 1981 alle ore 21:45 nel proprio garage di casa di via Cimaglia a Torre del Greco, Cirillo fu sequestrato da un commando di cinque appartenenti alle Brigate Rosse, capeggiati da Giovanni Senzani[3]. Durante il conflitto a fuoco morirono l'agente di scorta maresciallo di P.S. Luigi Carbone e l'autista Mario Cancello, mentre viene gambizzato il segretario dell'allora assessore campano all'urbanistica, Ciro Fiorillo[4]. -

Download the History Book In

GHELLA Five Generations of Explorers and Dreamers Eugenio Occorsio in collaboration with Salvatore Giuffrida 1 2 Ghella, Five Generations of Explorers and Dreamers chapter one 1837 DOMENICO GHELLA The forefather Milan, June 1837. At that time around 500,000 people live in At the head of the city there is a new mayor, Milan, including the suburbs in the peripheral belt. Gabrio Casati. One of these is Noviglio, a rural hamlet in the south of the city. He was appointed on 2 January, the same day that Alessandro Manzoni married his second wife Teresa Borri, following the death of Enrichetta Blondel. The cholera epidemic of one year ago, which caused It is here, that on June 26 1837 Domenico Ghella more than 1,500 deaths, is over and the city is getting is born. Far away from the centre, from political life back onto its feet. In February, Emperor Ferdinand and the salon culture of the aristocracy, Noviglio is I of Austria gives the go-ahead to build a railway known for farmsteads, rice weeders, and storks which linking Milan with Venice, while in the city everyone come to nest on the church steeples from May to is busy talking about the arrival of Honoré de Balzac. July. A rural snapshot of a few hundred souls, living He is moving into the Milanese capital following an on the margins of a great city. Here Dominico spends inheritance and apparently, to also escape debts his childhood years, then at the age of 13 he goes to accumulated in Paris. France, to Marseille, where he will spend ten long years working as a miner. -

Italy Report

Country Report Italy Tina Magazzini November 2019 This Country Report offers a detailed assessment of religious diversity and violent religious radicalisation in the above-named state. It is part of a series Covering 23 countries (listed below) on four Continents. More basiC information about religious affiliation and state-religion relations in these states is available in our Country Profiles series. This report was produCed by GREASE, an EU-funded research project investigating religious diversity, seCularism and religiously inspired radiCalisation. Countries covered in this series: Albania, Australia, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Egypt, FranCe, Germany, Greece, Italy, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Lebanon, Lithuania, Malaysia, Morocco, Russia, Slovakia, Spain, Tunisia, Turkey and the United Kingdom. http://grease.eui.eu The GREASE projeCt has reCeived funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement number 770640 Italy Country Report GREASE The EU-Funded GREASE project looks to Asia for insights on governing religious diversity and preventing radicalisation. Involving researChers from Europe, North AfriCa, the Middle East, Asia and OCeania, GREASE is investigating how religious diversity is governed in over 20 Countries. Our work foCuses on Comparing norms, laws and praCtiCes that may (or may not) prove useful in preventing religious radiCalisation. Our researCh also sheds light on how different soCieties Cope with the Challenge of integrating religious minorities and migrants. The aim is to deepen our understanding of how religious diversity Can be governed suCCessfully, with an emphasis on countering radiCalisation trends. While exploring religious governanCe models in other parts of the world, GREASE also attempts to unravel the European paradox of religious radiCalisation despite growing seCularisation. -

Analysis of Organized Crime: Camorra

PREGLEDNI ČLANCI UDK 343.974(450) Prihvaćeno: 12.9.2018. Elvio Ceci, PhD* The Constantinian University, New York ANALYSIS OF ORGANIZED CRIME: CAMORRA Abstract: Organized crime is a topic that deserves special attention, not just in criminal science. In this paper, the author analyzes Italian crime organizations in their origins, features and relationships between them. These organizations have similar patterns that we will show, but the main one is the division between government and governance. After the introductory part, the author gives a review of the genesis of the crime, but also of the main functions of criminal organizations: control of the territory, monopoly of violence, propensity for mediation and offensive capability. The author also described other organizations that act on the Italian soil (Cosa Nostra, ‘Ndrangheta, Napolitan Camora i Apulian Sacra Coroina Unita). The central focus of the paper is on the Napolitan mafia, Camorra, and its most famous representative – Cutolo. In this part of the paper, the author describes this organization from the following aspects: origin of Camorra, Cutulo and the New Organized Camorra, The decline of the New Organized Camorra and Cutolo: the figure of leader. Key words: mafia, governance, government, Camorra, smuggling. INTRODUCTION Referring to the “culturalist trend” in contemporary criminology, for which the “criminal issue” must include what people think about crime, certain analysts study- ing this trend, such as Benigno says, “it cannot be possible face independently to cultural processes which define it”.1 Concerning the birth of criminal organizations, a key break occured in 1876 when the left party won the election and the power of the State went to a new lead- ership. -

Zoznam Zbraní, Ktoré Sa Môžu Zaradiť Do Kategórie B Podľa § 5 Ods. 1 Písm

Príloha č. 1 Zoznam zbraní, ktoré sa môžu zaradiť do kategórie B podľa § 5 ods. 1 písm. f) zákona č. 190/2003 Z.z. v znení neskorších predpisov Československo/ Česko : - samonabíjacia verzia Sa vz. 58, SA VZOR 58, ČZ 58, ČZ 58 COMPACT, SA VZ. 58 COMPACT, SA VZ. 58 SUBCOMPACT, SA VZOR 58 – SEMI, SAMOPAL VZOR 58, VZ. 58. I.P.S.C, IPSC GUĽOVNICA, CZ 858 TACTICAL, ARMS SPORTER, CZH 2003 S/K, FSN 01, FSN 01 LUX, FSN 01 URBAN - samonabíjacia verzia Sa vz. 23, 24, 25, 26, Sa vz. 61, - CZ 91S - samonabíjacia verzia guľometu vz. 26 - semiverzia CZ 805 Bren, CZ EVO Rusko a iné : - samonabíjacia verzia – PPŠ 41, PPS 43 - samonabíjacia verzia AK-47, AK 47 AKM, AK 74, AKS-74, AK – 101, 102, 103, 104, 105 , AK 107/108, AK-74, AKM, AKS - SAIGA Maďarsko: Verzie AKM, AMD, AK-63F 1 NDR Verzie AK47 Jugoslávia : Verzie M70AB1, M70AB2 Nemecko : Upravené do samonabíjacieho režimu streľby, resp. semi verzie - MP-18, MP-38, MP38/40, MP40, MP41, FG 42, MKb 42 (H), MKb 42(W), MP43, MP 44, HK G3, HK 33, HK 53, HK G36, HK SL8, HK 416, HK 417, semi HK MP5, GSG5, Nemecku vyrábaju nanovo samonabíjacie kópie vojnových samočinných zbrani pod novými názvami (prave pod nimi môzu byt dovezene) – pre ujasnenie vedľa v zátvorke uvádzame originálne zbrane, ktoré imitujú: BD 38 (MP 38) BD 3008 (MP 3008 – to je okopírovaný Sten) BD 42/I (FG 42/I) BD 42/II (FG 42/II) BD 42 (H) (MKB 42 H) BD 43/I (MP 43/I) BD 44 (MP 44) BD 1-5 (VG 1-5) Rakúsko : Samonabíjacia verzia Steyr AUG – 2, AK-INTERORDNANCE Belgicko : Samonabíjacia verzia FN FAL, FN CAL, FN FNC, FN F2000, FN SCAR SEMI AUTO Izrael : Úprava - Samonabíjacia verzia GALIL, GALIL ACE, GALIL ARM, GALIL SAR Úprava – UZI, Micro Uzi Španielsko : Samonabíjacie úpravy CETME verzie B,C,L Rumuni: Verzie AK-47 - AKM USA: Samonabíjacia verzia – Thompson 1928, Thompson M1A1 Samonabíjacia verzia – úprava/originál : - M-16, M-16A1, M-16A2, M-16A3, M-16A4, AR-10, AR-15, AR-18, M4, M4A1, Ruger Mini M14, Bushmaster M14, M16, M4, klony M16 a M4 – v USA je veľa firiem vyrábajúcich tieto klony (napr. -

Paraguay Country Report

SALW Guide Global distribution and visual identification Paraguay Country report https://salw-guide.bicc.de Weapons Distribution SALW Guide Weapons Distribution The following list shows the weapons which can be found in Paraguay and whether there is data on who holds these weapons: Beretta AR70/90 G IWI NEGEV G Browning M 2 G M79 G CZ Scorpion G Mauser K98 U FN FAL G MP UZI G FN High Power U SIG SG540 G HK G3 G Explanation of symbols Country of origin Licensed production Production without a licence G Government: Sources indicate that this type of weapon is held by Governmental agencies. N Non-Government: Sources indicate that this type of weapon is held by non-Governmental armed groups. U Unspecified: Sources indicate that this type of weapon is found in the country, but do not specify whether it is held by Governmental agencies or non-Governmental armed groups. It is entirely possible to have a combination of tags beside each country. For example, if country X is tagged with a G and a U, it means that at least one source of data identifies Governmental agencies as holders of weapon type Y, and at least one other source confirms the presence of the weapon in country X without specifying who holds it. Note: This application is a living, non-comprehensive database, relying to a great extent on active contributions (provision and/or validation of data and information) by either SALW experts from the military and international renowned think tanks or by national and regional focal points of small arms control entities. -

Brazil Country Handbook 1

Brazil Country Handbook 1. This handbook provides basic reference information on Brazil, including its geography, history, government, military forces, and communications and trans- portation networks. This information is intended to familiarize military personnel with local customs and area knowledge to assist them during their assignment to Brazil. 2. This product is published under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Defense Intelligence Production Program (DoDIPP) with the Marine Corps Intel- ligence Activity designated as the community coordinator for the Country Hand- book Program. This product reflects the coordinated U.S. Defense Intelligence Community position on Brazil. 3. Dissemination and use of this publication is restricted to official military and government personnel from the United States of America, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, NATO member countries, and other countries as required and designated for support of coalition operations. 4. The photos and text reproduced herein have been extracted solely for research, comment, and information reporting, and are intended for fair use by designated personnel in their official duties, including local reproduction for train- ing. Further dissemination of copyrighted material contained in this document, to include excerpts and graphics, is strictly prohibited under Title 17, U.S. Code. CONTENTS KEY FACTS. 1 U.S. MISSION . 2 U.S. Embassy. 2 U.S. Consulates . 2 Travel Advisories. 7 Entry Requirements . 7 Passport/Visa Requirements . 7 Immunization Requirements. 7 Custom Restrictions . 7 GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE . 8 Geography . 8 Land Statistics. 8 Boundaries . 8 Border Disputes . 10 Bodies of Water. 10 Topography . 16 Cross-Country Movement. 18 Climate. 19 Precipitation . 24 Environment . 24 Phenomena . 24 TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNICATION . -

AN/SO/PO 350 ORGANIZED CRIME in ITALY: MAFIAS, MURDERS and BUSINESS IES Abroad Rome Virtual World Discoveries Program

AN/SO/PO 350 ORGANIZED CRIME IN ITALY: MAFIAS, MURDERS AND BUSINESS IES Abroad Rome Virtual World DiscoverIES Program DESCRIPTION: This course analyzes the role of organized crime in Italy through historical, structural, and cultural perspectives. After an overview of the various criminal organizations that are active both in Italy and abroad, the course will focus mainly on the Sicilian mafia, Cosa Nostra. Discussion topics will include both mafia wars, the importance of the investigators Falcone and Borsellino, the Maxi Trial, and the anti-mafia state organizations, from their origins to their role today in the struggle against organized crime. The course will highlight the creation of the International Department against Mafia and the legislation developed specifically to aid in the fight against criminal organizations. It will examine the ties between Cosa Nostra and Italian politics, the period of terrorist attacks, and response of the Italian government. Finally, the course will look at the other two most powerful criminal organizations in Italy: the Camorra, especially through the writings of Roberto Saviano, and the Ndrangheta, today’s richest and most powerful criminal organization, which has expanded throughout Europe and particularly in Germany, as evidenced by the terrorist attack in Duisburg. CREDITS: 3 credits CONTACT HOURS: Students are expected to commit 20 hours per week in order complete the course LANGUAGE OF INSTRUCTION: English INSTRUCTOR: Arije Antinori, PhD VIRTUAL OFFICE HOURS: TBD PREREQUISITES: None METHOD OF -

Milan and the Memory of Piazza Fontana Elena Caoduro Terrorism

Performing Reconciliation: Milan and the Memory of Piazza Fontana Elena Caoduro Terrorism was arguably the greatest challenge faced by Western Europe in the 1970s with the whole continent shaken by old resentments which turned into violent revolt: Corsican separatists in France, German speaking minorities in Italy’s South Tyrol, and Flemish nationalists in Belgium. Throughout that decade more problematic situations escalated in the Basque Provinces and Northern Ireland, where ETA and the Provisional IRA, as well as the Loyalist paramilitary groups (such as the UVF, and UDA) participated in long armed campaigns. According to Tony Judt, two countries in particular, West Germany and Italy, witnessed a different violent wave, as the radical ideas of 1968 did not harmlessly dissipate, but turned into a ‘psychosis of self- justifying aggression’ (2007, p. 469). In Italy, the period between 1969 and 1983, where political terrorism reached its most violent peak, is often defined as anni di piombo, ‘the years of lead’. This idiomatic expression derives from the Italian title given to Margarethe Von Trotta’s Die bleierne Zeit (1981, W. Ger, 106 mins.), also known in the UK as The German Sisters and in the USA as Marianne and Juliane.1 Following the film’s Golden Lion award at the 1981 Venice Film Festival, the catchy phrase ‘years of lead’ entered common language, and is now accepted as a unifying term for the various terrorist phenomena occurred in the long 1970s, both in Italy and West Germany. By the mid 1980s, however, terrorism had begun to decline in Italy. Although isolated episodes of left-wing violence continued to occur – two governmental consultants were murdered in 1999 and in 2002 respectively – special laws and the reorganisation of anti-terrorist police forces enabled its eradication, as did the 1 collaboration of many former radical militants. -

Beretta 70.Pdf

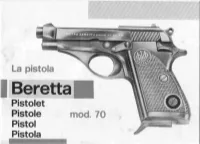

.. FABBRICA d'ARMI P. BERETTA S.p.A. ~ Gardone V. T. (Brescia) L'ESPERIENZA PIU' ANTICA LA TECNICA PIU' PROGREDITA I MA TERIALI PIU' EFFICIENT! hanno consentlto dl mettere 8 punto Ie pistole BERm A Mod. 70. La plstola Mod. 70 castruita nei calibri 7.65 e .22 L. R. (mm. 5,6) e Indubbiamente un'arma nUOV8, concepita e impostata come struttura sull~ glori058 BERm A 935 la cui diffuslone nel mondo - nei 30 annl compluti ha raggiunto milionl dl esemplarl. - La plstola Mod. 70. con qucste origini s'i"serisce nel si- curo cammino produttivo delle armi BERm A. La pistola Mod. 70 e un'arma automatica del tipo classico con chiusura a massa (blow-back). con otturatore rincu- lante per effetto dell'8zione diretta del gas sui fondello del bossola. Mantenendo 10 .stesso principia di funzionamento per i disposltivl di scatto, alimentazione e sicurt:ZZ8. la pistola e fabbricata. oltre che nel Mod. 70 per la cartuccla a per- cussione centrale calibro 7.65. anche nei modelli derivati Mod. 71. 72 - 73 . 74 . 75. per Ie cartucce a percusslone anulare cal. .22 L. R. (mm. 5.6). (Per 18 descrllione del v8rl modem vedas I II pag. 24-25]- 3 LES PISTOLETS .. BERETTA. .. BERETTA.. PISTOLE MOD. 70 SERlE 70 les pistolets BERETTAde la serie 70 Die BERETTA-Pistole Mod. 70 1st das ont ete conc;us compte tenu de I'expe. Ergebnis der fortgeschrittenen Technik. rience consecutive a une production der Verwendung der neuesten Ouali. de plus de dix millions d'armes diver- tatsmaterialien und unserer weitge- ses et des principes ayant fait Ie suc. -

Behind a Veil of Secrecy:Military Small Arms and Light Weapons

16 Behind a Veil of Secrecy: Military Small Arms and Light Weapons Production in Western Europe By Reinhilde Weidacher An Occasional Paper of the Small Arms Survey Copyright The Small Arms Survey Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey The Small Arms Survey is an independent research project located at the Grad © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International Studies, Geneva 2005 uate Institute of International Studies in Geneva, Switzerland. It is also linked to the Graduate Institute’s Programme for Strategic and International Security First published in November 2005 Studies. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in Established in 1999, the project is supported by the Swiss Federal Depart a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the ment of Foreign Affairs, and by contributions from the Governments of Australia, prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permit Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, the Netherlands, New Zealand, ted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. It collaborates with research insti organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above tutes and nongovernmental organizations in many countries including Brazil, should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address Canada, Georgia, Germany, India, Israel, Jordan, Norway, the Russian Federation, below. South Africa, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Thailand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Small Arms Survey The Small Arms Survey occasional paper series presents new and substan Graduate Institute of International Studies tial research findings by project staff and commissioned researchers on data, 47 Avenue Blanc, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland methodological, and conceptual issues related to small arms, or detailed Copyedited by Alex Potter country and regional case studies.