Fanfan Chen the Threefold Mimesis of Evil in the Myths of Formosan Aborigines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Dynamics and Existence of Traveling Wave Solutions for a Three-Species Models

Global Dynamics and Existence of Traveling Wave Solutions for A Three-Species Models Fanfan Li1, Zhenlai Han1, and Ting-Hui Yang∗2 1School of Mathematical Sciences, University of Jinan, Jinan, Shandong 250022, P R China. 2Department of Mathematics, Tamkang University, Tamsui Dist., New Taipei City 25137, Taiwan. Abstract In this work, we investigate the system of three species ecological model involving one predator-prey subsystem coupling with a general- ist predator with negative effect on the prey. Without diffusive terms, all global dynamics of its corresponding reaction equations are proved analytically for all classified parameters. With diffusive terms, the transitions of different spatial homogeneous solutions, the traveling wave solutions, are showed by higher dimensional shooting method, the Wazewski method. Some interesting numerical simulations are performed, and biological implications are given. 2010 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary: 37N25, 35Q92, 92D25, 92D40. Keywords : Two predators-one prey system, extinction, coexistence, global asymptotically stability, traveling wave solutions, Wazewski principle. arXiv:2004.12263v1 [math.DS] 26 Apr 2020 ∗Research was partially supported by Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (R O C). 1 1 Introduction In this work, we consider an ecological system of three species with diffusion as follows, 8 @ u = r u(1 − u) − a uv − a uw; <> t 1 12 13 @tv = r2v(1 − v) + a21uv; (1.1) > : @tw = d∆w − µw + a31uw; where parameters d is the diffusive coefficient for species w, r1 and r2 are the intrinsic growth rates of species u and v respectively, and µ is the death rate of the predator w. The nonlinear interactions between species is the Lotka- Volterra type interactions between species where aij(i < j) is the rate of consumption and aij(i > j) measures the contribution of the victim (resource or prey) to the growth of the consumer [19]. -

2017 Annual Report 147,751

“Libraries are the FOUNDATION for learning.” —Mark Davis 2017 Annual Report 147,751 media streams 1,096,762 checkouts ebook downloads 421,515 737,358 ebooks 15,061 reserve checkouts its 47,116 reference questions answered 70,560 hours is reserved in V 1,944 classes taught to Group Study Roomsour 33,702 students 48% 3,208,295 online 2,938,623 4,394,088 in-person print volumes Table of Contents 52% Collections ................................ 2 48,129 hours open Discovery ..................................3 Open and Affordable 52,244 interlibrary loans Textbooks Program ..............4 facilitated ORCID ........................................5 44,378 Rutgers to Rutgers deliveries Newark .......................................6 Institute of Jazz Studies ...........8 Special Collections and University Archives ...............9 New Brunswick .......................10 Camden ...................................12 RBHS .......................................14 Donor Thank Yous ..................16 Annual Report design: Faculty and Staff News ..........18 Jessica Pellien Welcome I am so proud to share this year’s annual report with you. The stories collected here demonstrate Rutgers University Libraries’ commitment to supporting the mission of Rutgers University and to building a strong foundation for academic success and research. Thanks to the publication of a large, rigorous new study, “The Impact of Academic Library Resources on Undergraduates’ Degree Completion,” we know that academic libraries can have a big impact on student outcomes. This bodes well for the thousands of students who use the Libraries each day, but it also means we have to make sure our core services meet their needs and expectations and that we are ready to support them throughout their academic careers. This year, we made significant improvements to our collections, instruction, and discovery, adding thousands of new resources and making them easier to find. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from tfie original or copy submitted. Thus, some tfiesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter ftice, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, tfiese will be noted. Also, if unautfiorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Leaming 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI’ FINAL PARTICLES IN STANDARD CANTONESE: SEMANTIC EXTENSION AND PRAGMATIC INFERENCE DISSERTAnON Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Roxana Suk-Yee Fung, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2000 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Marjorie Chan, Adviser Professor Timothy Light Professor Galal Walker AcMsér Professor Jianqi Wang nt of East Asian Languages and Literatures UMI Number 9971549 Copyright 2000 by Fung, Roxana Suk-Yee All rights reserved. -

FINAL PROGRAM Crystal Gateway Marriott Arlington, Virginia, USA December 10 - 14, 2017 2017 Program Committee

SR A 2017 RISK ANALYSIS The Profession · The Practitioners · The Research FINAL PROGRAM Crystal Gateway Marriott Arlington, Virginia, USA December 10 - 14, 2017 2017 Program Committee Terje Aven Stanley Jennifer Jill Drupa Natalie Judd Melanie Preve Britania Levinson Rosenberg Weinstein Amanda Bailey Tony Barrett Ken Bogen Weihsueh Chiu Chris Clarke Roger Flage Royce Francis Jeremy Chris Greene Gernand Tee Guidotti Seth Guikema Kirk T. Hartley Sandra Danail Hristozov Amber Jessup Debra Kaden James H. John Lathrop Hoffmann Lambert Steve Lewis Margaret Amir Mokhtari Roshi Nateghi Abani Pradhan Allison Reilly Vanessa Amina Wilkins Matthew Wood MacDonell Schweizer Society For Risk Analysis Annual Meeting 2017 Final Program Meeting Highlights Table of Contents Meeting Events! All events take place at the Crystal Gateway Marriott, starting with the opening reception on Sunday, December 10, 6:00-7:30 PM (Cash Bar), and continuing to the closing t-shirt giveaway and raffle Council and Program Committee . 2 with a possibility of winning a trip to Norway, December 13, 5:00 PM . The meeting includes three plenary Conference Events/Committee Meetings . .3 sessions and complimentary box lunch on Monday, Awards Banquet lunch on Tuesday (comes with your Award Winners . 4 registration), and a plenary luncheon on Wednesday (also included in your registration fee) . Don’t forget Specialty Group Meetings, Mixers . 5 workshops on Sunday and Thursday - there is still room! Registration Hours . 5 Meeting Theme – “Risk Analysis – the Profession, the Practitioners, the Research” highlights the important role risk analysts have in tackling risk problems and improving the science and practice of risk analysis . Exhibitors/Exhibition Hours . -

Download the 2021 Commencement Book

UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER ONE HUNDRED SEVENTY-FIRST COMMENCEMENT MAY 2021 3613_BigBook_Text_v2.indd 1 5/10/21 12:05 PM 3613_BigBook_Text_v2.indd 2 5/10/21 12:05 PM Honorary Awards, 4 Honor Societies and Awards, 8 Doctoral Degree Candidates, 11 University Council on Graduate Studies, 11 Doctor of Philosophy, 11 School of Nursing, 12 Doctor of Nursing Practice, 12 Eastman School of Music, 13 Doctor of Musical Arts, 13 Margaret Warner Graduate School of Education and Human Development, 13 Doctor of Education, 13 Degree Candidates, 14 School of Arts & Sciences, 14 Bachelor of Arts, 14 Bachelor of Science, 19 Master of Arts, 24 Master of Science, 24 Edmund A. Hajim School of Engineering & Applied Sciences, 26 Bachelor of Arts, 26 Bachelor of Science, 26 Master of Science, 29 Eastman School of Music, 31 Bachelor of Music, 31 Master of Arts, 32 Master of Music, 32 School of Medicine and Dentistry, 33 Doctor of Medicine and Doctor of Philosophy, 33 Doctor of Medicine with Distinction in Research and Distinction in Community Health, 33 Doctor of Medicine with Distinction in Community Health, 33 Doctor of Medicine with Distinction in Research, 33 Doctor of Medicine, 33 Master of Arts, 34 Master of Public Health, 34 Master of Science, 34 School of Nursing, 35 Bachelor of Science, 35 Master of Science, 36 Eastman Institute for Oral Health, 36 Master of Science, 36 Margaret Warner Graduate School of Education and Human Development, 37 Master of Science, 37 The Genesee, 40 3613_BigBook_Text_v2.indd 3 5/10/21 12:05 PM Honorary Awards Eastman Medal The Eastman Medal Doctor of Science George Eastman Medal recognizes individuals James Wyant ’67 (MS), ’69 (PhD) John “Dutch” Summers who, through their out- standing achievement James Wyant is a professor John “Dutch” Summers is and dedicated service, emeritus and the founding an entrepreneur and the embody the high ideals for which the University dean of the James C. -

INSIDE THIS ISSUE Year in Pictures — 2, 3 CONGRATULATORY NOTE

Spring 2013 Issue INSIDE THIS ISSUE Year in Pictures — 2, 3 CONGRATULATORY NOTE “Congratulations to the Milestone Achievement, 21st Year of Hosting Black Executive Exchange Program (BEEP) — 3 Reginald F. Lewis School of Business on securing It’s Tax Season; Accounting Students Prepare Tax Returns — 3 reaffirmation of your AACSB accreditation. Accreditation is Did someone say Ni hao? Students depart for China — 3 the bread and butter of academia.” Project Shadow on NBC — 4 W. Weldon Hill, Ph.D., Provost Three Faculty Earn Ph.D.s — 4 “On behalf of faculty, staff, and students, we are grateful Student organizes Toy Drive for Haiti — 5 to Dr. Miller, Dr. Hill, our Industry Boards and all others who supported the Industry Council(s) hear from President — 5 Reginald F. Lewis School of Business in its AACSB Students participate in City of Hopewell’s rebirth — 5 Maintenance of Accreditation quest. Congratulations on a Commonwealth Center for Advanced Manufacturing (CCAM) leans on business students for support — 5 job well-done! Everyone worked extremely hard to Accounting graduate first to finish program at V.C.U. — 5 attain this important milestone. Thank you!” Mirta M. Martin, Ph.D., Dean Students produce commercial for RVA — 6 Interview(s) with a student, alum, industry stakeholder, and faculty — 6, 7, 8 Page 1 Dean of Business School Awarded Humanitarian Award — 8 2012: THE YEAR IN PICTURES Page 2 Milestone Achievement, 21st Year of Hosting Black Executive Exchange Program (BEEP) Sponsored by the Urban League Inc, the Reginald F. Lewis School of Business for the 21st year hosted the Black Executive Exchange Program (BEEP). -

May 6-8, 2021 Live the Ucf Creed

UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL FLORIDA COMMENCEMENT MAY 6-8, 2021 LIVE THE UCF CREED INTEGRITY I will practice and defend academic and personal honesty. SCHOLARSHIP I will cherish and honor learning as a fundamental purpose of my membership in the UCF community. COMMUNITY I will promote an open and supportive campus environment by respecting the rights and contributions of every individual. CREATIVITY I will use my talents to enrich the human experience. EXCELLENCE I will strive toward the highest standards of performance in any endeavor I undertake. UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL FLORIDA | COMMENCEMENT | MAY 6-8, 2021 About the University of Central Florida The University of Central Florida is a bold, preeminent research institution that is regularly ranked among the nation’s top 20 most innovative universities by U.S News & World Report. With more than 71,500 students, UCF is one of the largest universities in the United States and is ranked as one of the best educational values in the nation by Forbes and Kiplinger. The university benefits from a diverse faculty and staff who create a welcoming environment and opportunities for all students to grow, learn, and succeed. A Foundation for Success UCF and its 13 colleges offer more than 220 degrees at UCF AT A GLANCE UCF’s main campus, hospitality campus, health sciences campus, and through multiple regional locations. The 1,415-acre main campus is 13 miles east of downtown Dr. Alexander N. Orlando and adjacent to one of the top research parks in the nation. Other campuses throughout Central Florida Cartwright include a fully accredited College of Medicine at Lake UCF PRESIDENT SINCE APRIL 13, 2020 Nona and UCF Downtown, which opened in fall 2019 and provides innovative urban education for high-demand FOUNDED ON JUNE 10, 1963 fields such as digital media and health informatics. -

Library-Catalog-Updated-2021-01-04-07 Pàgina 1 Composer and Sheet Music Name (Pdf Or Rar File) File Size (KB) 100 Greatest

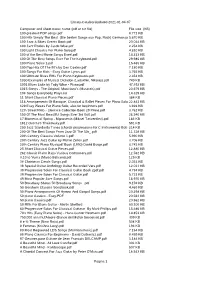

Library-Catalog-Updated-2021-01-04-07 Composer and sheet music name (pdf or rar file) File size (KB) 100 greatest POP songs.pdf 8.771 KB 100 Hits Simply The Best (Die besten Songs aus Pop, Rock) German.pd5.670 KB 100 Jazz & Blues Greats Book.pdf 20.044 KB 100 Jazz Etudes by Jacob Wise.pdf 2.254 KB 100 Light Classics For Piano Solo.pdf 4.810 KB 100 of the Best Movie Songs Ever!.pdf 14.313 KB 100 Of The Best Songs Ever For The Keyboard.pdf 29.986 KB 100 Piano Solos 1.pdf 15.465 KB 100 Pop Hits Of The 90's by Dan Coates.pdf 7.180 KB 100 Songs For Kids - Easy Guitar Lyrics.pdf 3.765 KB 100 Ultimate Blues Riffs For Piano Keyboards.pdf 2.351 KB 1000 Examples of Musical Dictation (Ladukhin, Nikolay).pdf 749 KB 1001 Blues Licks by Toby Wine - Piano.pdf 47.492 KB 1015 Songs - The Original, Musicians's (Musicals).pdf 20.679 KB 106 Songs Everybody Plays.rar 14.329 KB 11 Short Classical Piano Pieces.pdf 384 KB 116 Arrangements Of Baroque, Classical & Ballet Pieces For Piano Solo.22.841 KB 129 Easy Pieces For Piano Solo, also for beginners.pdf 3.926 KB 12th Street RAG - Liberace Collection Book 29 Piano.pdf 3.762 KB 150 Of The Most Beautiful Songs Ever 3rd Edit.pdf 26.540 KB 17 Moments of Spring - Mgnovenia (Mikael Tariverdiev).pdf 183 KB 1812 Overture Thaikovsky.pdf 591 KB 200 Jazz Standards Tunes (chords progressions for C Instruments) Bob T214 KB 200 Of The Best Songs From Jazz Of The 50s_.pdf 11.328 KB 20th Century Classics Volume 1.pdf 5.990 KB 20th Century Jazz Guitar by Richie Zellon.pdf 3.706 KB 20th Century Piano Musicpdf Book (1990) David -

2015 NRCAL Chinese Film Book 6

Studies in Chinese Film Society and Media 1 Studies in Chinese Film Society and Media 2 The procedures Chinese film teaching This book uses the comparison analysis of movies to better understand Chinese culture. Teaching Method Students will watch two movies with similar stories and compare the culture differences. Focus on the teenage issues, family conflicts, cross-cultural differences, etc. Movie Questions Students are supposed to watch the movie outside of class. And provide 2 Questions w/time stamp from movie Movie Review: The class will consider larger questions of globalization, new media, and the dominance of communism government as they become configured through film and media. This course is an introduction to the analysis of film as both a textual practice and a cultural practice. What should movie writer critic? Should essay only focuses on the plot? Or Actors performance? We will examine a variety of Chinese film in order to demonstrate the tools and skills of "close reading." We will concentrate on those specifically filmic features of the movies, such as new media/weibo, Chinese people lifestyle. Because our discussion to the movies always extend beyond the film frame, we will additionally do “cultural analysis” of the scents to show how the contemporary film shapes our understanding china social reality. Screenings are mandatory. However both US and China have some limitation when it comes to censorship since in the US there are conservative parents that are anal when it comes to what their child should watch and assigns a movie rating meanwhile in China the government will limit their movie production freedom regarding some topics. -

Implications of the Booker/Fanfan Deci- Sions for the Federal Sentencing Guide- Lines

IMPLICATIONS OF THE BOOKER/FANFAN DECI- SIONS FOR THE FEDERAL SENTENCING GUIDE- LINES HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON CRIME, TERRORISM, AND HOMELAND SECURITY OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION FEBRUARY 10, 2005 Serial No. 109–1 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.house.gov/judiciary U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 98–624 PDF WASHINGTON : 2005 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 13:45 Apr 04, 2005 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 G:\WORK\CRIME\021005\98624.000 HJUD1 PsN: DOUGA COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., Wisconsin, Chairman HENRY J. HYDE, Illinois JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina HOWARD L. BERMAN, California LAMAR SMITH, Texas RICK BOUCHER, Virginia ELTON GALLEGLY, California JERROLD NADLER, New York BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia ROBERT C. SCOTT, Virginia STEVE CHABOT, Ohio MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California ZOE LOFGREN, California WILLIAM L. JENKINS, Tennessee SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas CHRIS CANNON, Utah MAXINE WATERS, California SPENCER BACHUS, Alabama MARTIN T. MEEHAN, Massachusetts BOB INGLIS, South Carolina WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Massachusetts JOHN N. HOSTETTLER, Indiana ROBERT WEXLER, Florida MARK GREEN, Wisconsin ANTHONY D. WEINER, New York RIC KELLER, Florida ADAM B. SCHIFF, California DARRELL ISSA, California LINDA T. SA´ NCHEZ, California JEFF FLAKE, Arizona ADAM SMITH, Washington MIKE PENCE, Indiana CHRIS VAN HOLLEN, Maryland J. -

Thepromiseofabrighterfuture

THE PROMISE OF A BRIGHTER FUTURE Boys & Girls Club of Worcester 65 Tainter Street • Worcester, MA 01610 Administration: (508)754-2686 • Main South Clubhouse: (508)753-3377 • Fax: (508)754-7635 [email protected] • www.bgcworcester.org Child Development Center 65 Tainter St • Worcester, MA 01610 • Phone: 508-754-0796 • Fax: 508-754-7635 Great Brook Valley Clubhouse 35 - 45 Freedom Way • Worcester, MA 01605 • Phone: 508-421-5176 Freedom Way Gymnasium 33 Freedom Way • Worcester, MA 01605 • Phone: 508-421-5176 Kids Club Clubhouse 180 Constitution Ave. • Worcester, MA 01605 • Phone: 508-459-3634 Plumley Village Clubhouse 16 Laurel Street • Worcester, MA 01608 • Phone: 508-754-5509 portions of our programs provided by: ANNUAL REPORT 2007 – 2008 THE BOYS & GIRLS CLUB IS THE BEST INVESTMENT THAT YOU CAN MAKE IN YOUTH IN WORCESTER With so many non-profits, coalitions and community ideas vying for our limited time, energy and dollars, it’s more important than ever that each of us makes the most of our opportunity to invest in programs that you know work. By supporting the Boys & Girls Club of Worcester and telling others about how the Club is improving the lives of the kids we reach, you will help us continue to make an important and life-saving difference for our kids. The Boys & Girls Club of Worcester is embarking on a bold four-year initiative to deepen the positive impact on young people’s lives. We are beginning to recruit a stadium full of Raving Fans empowered to enlist others to support the growing impact that the Club is making on our youth members and the City of Worcester. -

Respondent's Brief in United States V. Fanfan, 04-105

No. 04-105 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ___________ UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Petitioner, v. DUCAN FANFAN, Respondent. ___________ On Writ of Certiorari Before Judgment to the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit ___________ BRIEF OF RESPONDENT ___________ CARTER G. PHILLIPS ROSEMARY CURRAN JEFFREY T. GREEN SCAPICCHIO* ERIC A. SHUMSKY Four Longfellow Place MICHAEL C. SOULES Suite 3703 ANDREW D. FAUSETT Boston, Massachusetts 02114 MATTHEW J. WARREN (617) 263-7400 SIDLEY AUSTIN BROWN & WOOD LLP BRUCE M. MERRILL 1501 K Street, N.W. BRUCE M. MERRILL, P.A. Washington, D.C. 20005 225 Commercial Street (202) 736-8000 Suite 401 Portland, ME 04101 (207) 775-3333 Counsel for Respondent [Additional counsel listed on inside cover] September 21, 2004 * Counsel of Record ROBERT N. HOCHMAN SCOTT D. MARCUS SIDLEY AUSTIN BROWN &SIDLEY AUSTIN BROWN & WOOD LLP WOOD LLP Bank One Plaza 555 West 5th Street 10 South Dearborn Street 40th Floor Chicago, IL 60603 Los Angeles, CA 90013 (312) 853-7000 (213) 896-6600 MARTIN G. WEINBERG MARTIN G. WEINBERG P.C. 20 Park Plaza Boston, MA 02116 (617)227-3700 QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1. Whether the Sixth Amendment is violated by the impo- sition of an enhanced sentence under the United States Sen- tencing Guidelines based on the sentencing judge’s determi- nation of a fact (other than a prior conviction) that was not found by the jury or admitted by the defendant. 2. Whether, in a case in which the Guidelines would re- quire the judge to find a sentence-enhancing fact, the Guide- lines as a whole would be inapplicable, as a matter of sever- ability analysis, or instead may be severed or reinterpreted in a manner consistent with the intent of the enacting Congress.