A Dutch Child Born in Indonesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kerentanan Wilayah Terhadap Erupsi Gunung Sindoro-Sumbing

Perpustakaan Universitas Indonesia >> UI - Skripsi (Open) Kerentanan wilayah terhadap erupsi Gunung Sindoro-Sumbing (Kabupaten Wonosobo-Temanggung, Jawa Tengah) = eruption vulnerability of Mount Sindoro-Sumbing (Wonosobo- Temanggung Regency, Central Java) Apriliana Deskripsi Dokumen: http://lib.ui.ac.id/opac/ui/detail.jsp?id=20317191&lokasi=lokal ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Abstrak Kerentanan merupakan derajat tingkat dimana manusia dengan sistem lingkungannya mengalami gangguan/tekanan akibat adanya bahaya yang terjadi dan dapat menimbulkan bencana atau tidak. Secara umum kajian terbaru tentang kerentanan sekarang ini telah mengalami pergeseran dari penilaian kerentanan tradisional yang hanya berkonsentrasi pada satu tekanan faktor atau sumber daya, menjadi banyak faktor yang mempengaruhinya. Penelitian ini, mengkaji tentang kerentanan sosial kependudukan, kerentanan ekonomi dan kerentanan fisik yang muncul dari bahaya erupsi Gunung Sindoro-Sumbing. Metode penelitian yang digunakan untuk menentukan tingkat kerentanan adalah pembobotan dari BNPB dan analisis spasial dari pola persebaran permukiman. Secara keseluruhan terdapat 112 desa yang masuk dalam zona bahaya Gunung Sindoro dan Gunung Sumbing dengan 41 desa termasuk dalam daerah administrasi Kabupaten Wonosobo dan 71 desa termasuk dalam daerah administrasi Kabupaten Temanggung. <hr> <b>Abstract</b><br> Vulnerability is the degree to which the human environment system disorders/stress due to hazards that occur and can lead to catastrophic or not. Recent studies on the vulnerability is now experiencing a shift from traditional vulnerability assessment concentrates only on one factor or resource, to a lot of factors that influence it. This study, examines the social vulnerability, economic vulnerability and physical vulnerability that arising from the hazard cause eruption of Mount Sindoro-Sumbing. This study use weighting methode from BNPB and spatial analisis of residence spread. -

Orientasi Pendopo Kabupaten Terhadap Laut Pada Kota-Kota Di Jawa Tengah Studi Komparasi : Kabupaten Wonosobo (Pesisir Selatan) Dengan Kota Tegal (Pesisir Utara)

Jurnal PPKM II (2015) 91-98 ISSN: 2354-869X ORIENTASI PENDOPO KABUPATEN TERHADAP LAUT PADA KOTA-KOTA DI JAWA TENGAH STUDI KOMPARASI : KABUPATEN WONOSOBO (PESISIR SELATAN) DENGAN KOTA TEGAL (PESISIR UTARA) Ardiyan Adhi Wibowoa, Muafanib a,bFakultas Teknik dan Ilmu Komputer Universitas Sains Al Qur’an (UNSIQ) Wonosobo aEmail: di [email protected] bEmail: [email protected] INFO ARTIKEL ABSTRAK Riwayat Artikel: Alun-alun dapat kita lihat pada setiap kota di Jawa, keberadaan alun-alun di pusat kota Diterima : 7 Maret 2015 ini merupakan identitas kota-kota di jawa pada masa lampau. Karena sejak masa pra- Disetujui : 30 Maret 2015 kolonial, konsep penataan alun-alun pada kota-kota di jawa ini sebenarnya telah ada, sehingga perlu kita sadari bersama mengenai konsep tata ruang kota Jawa di masa lampau. Pola dasar dari penataan alun-alun pada kota-kota di Jawa berasal dari jaman Kata Kunci: Hindu Jawa, sekalipun dalam perjalanan sejarah perkembangan kota di Jawa banyak alun-alun kota, pendopo terjadi perubahan pada fungsinya, tetapi pada kenyataannya, masih banyak kota-kota kabupaten, laut, orientasi kabupaten di Jawa yang sampai sekarang memakai alun-alun sebagai pusat dan sekaligus identitas untuk kotanya. Selain alun-alun itu sendiri, konsep dasar tata ruang alun-alun di Pulau Jawa juga tidak lepas dari keberadaan Pendopo Kabupaten. Konsep inilah yang sebetulnya menentukan fungsi dan kehadiran alun-alun di pulau Jawa. Yang menjadikan hal ini lebih manarik lagi untuk dijadikan sebagai bahan penelitian bahwa pendopo Kabupaten di pulau Jawa selalu berorientasi atau menghadap ke laut sehingga akan berbeda antara Orientasi Pendopo Kabupaten yang berada di Pesisir Selatan dengan Pesisir Utara pulau Jawa. -

Perumusan Strategi Pemasaran Untuk Kabupaten Wonosobo Sebagai Destinasi Berbasis Ekowisata

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PERUMUSAN STRATEGI PEMASARAN UNTUK KABUPATEN WONOSOBO SEBAGAI DESTINASI BERBASIS EKOWISATA TESIS PROGRAM STUDI MAGISTER MANAJEMEN Diajukan Oleh Muh Isra Iradat 172222104 FAKULTAS EKONOMI UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2019 PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PERUMUSAN STRATEGI PEMASARAN UNTUK KABUPATEN WONOSOBO SEBAGAI DESTINASI BERBASIS EKOWISATA TESIS UNTUK MEMENUHI SEBAGIAN PERSYARATAN MENCAPAI DERAJAT SARJANA S-2 PROGRAM STUDI MAGISTER MANAJEMEN Diajukan Oleh Muh Isra Iradat 172222104 FAKULTAS EKONOMI UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2019 i PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI LEMBAR PERSETUJUAN DOSEN PEMBIMBINO TESIS PERUMUSAN STRATEOl PEMASARAN UNTUK KABUPATEN WONOSOBO SEBAOAI DESTINASI BERBASIS EKOWISATA Diajukan oleh: Muh. Isra Iradat i 72222 104 Telah disetujui oleh dosen pembimbing Yogyakarta, Februari 2019 \ Ike Janita ewi, S.E., M.B.A., Ph.D ii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI LEMBAR PENGESAIIAN PERUMUSAN STRATEGI PEMASARAN UNTUK KABUPATEN WONOSOBO SEBAGAI DESTINASI BERBASIS EKOWISATA Oleh: Muh.Isra Iradat 17 2222 104 Tesis ini telah dipertahankan pada tanggal.12 Februari 2019 di depan Dewan Penguji yang terdiri dari: ;:-{i .g -l Dr. Titus versitas Sanata Dharma =d"q Prosram Studi GsE {.^H l"'&;nlxS' h,a Y Eko Prabowo, M.B.A.. Ph.D. ilt PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI KATA PENGANTAR Segala puji dan syukur dipanjatkan kehadirat Tuhan YME atas karunia- Nya sehingga penulis dapat menyelesaikan penulisan tesis ini dengan segala keterbatasan pengetahuan dan kemampuan. Tesis ini disusun dan diajukan guna melengkapi salah satu syarat yang harus dipenuhi untuk mencapai derajat sarjana S-2 pada Program Studi Magister Manajemen Fakultas Ekonomi Universitas Sanata Dharma. -

Master Thesis

ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT TO ALLEVIATE POVERTY IN RURAL HIGHLAND AGRICULTURAL AREAS THE CASE OF WONOSOBO REGENCY Master thesis A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master Degree from the Institut Teknologi Bandung and the Master Degree from the University of Groningen By: M. ARIF SETIAWAN ITB: 25410074 RuG: S2130475 DOUBLE MASTER DEGREE PROGRAMME DEVELOPMENT PLANNING AND INFRASTRUCTURE MANAGEMENT SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE, PLANNING AND POLICY DEVELOPMENT INSTITUT TEKNOLOGI BANDUNG AND ENVIRONMENTAL AND INFRASTRUCTURE PLANNING FACULTY OF SPATIAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF GRONINGEN 2012 ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT TO ALLEVIATE POVERTY IN RURAL HIGHLAND AGRICULTURAL AREAS THE CASE OF WONOSOBO REGENCY By: M. ARIF SETIAWAN ITB: 25410074 RuG: S2130475 Double Master Degree Programme Development Planning and Infrastructure Management Department of Regional and City Planning Institut Teknologi Bandung and Environmental and Infrastructure Planning Faculty of Spatial Sciences University of Groningen Approved Supervisors Date: August, 2012 Supervisor I Supervisor II (dr. J. R. Beaumont) (Heru Purboyo Hidayat P., Ir., DEA, Dr.) Abstract ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT TO ALLEVIATE POVERTY IN RURAL HIGHLAND AGRICULTURAL AREAS THE CASE OF WONOSOBO REGENCY By M. ARIF SETIAWAN ITB: 25410074 RuG: S2130475 Poverty is a crucial problem that is significantly related to economic development policy and the living need fulfillment. At the rural level, many serious challenges faced by people living in Wonosobo regency. Instead of natural factor conditions such extreme topography and crop pests and disease, poor rural people have also limited access to capital and productive land, lack adequate physical and social infrastructure and have insufficient access to services and information. However, since most of rural people who live in this region are engaged with commercial farming activity, the factor of accessibility and the availability of decent road infrastructure connecting with other region as well as to the market are the key factor. -

CALON PESERTA TES TERTULIS JULI 2021.Xlsx

PESERTA TES TERTULIS FORMASI S1 KEPERAWATAN JENJANG NO NAMA TEMPAT TANGGAL LAHIR ALAMAT LULUSAN PENDIDIKAN Rogojati RT 04 RW 01 Universitas Muhammadiyah 1 RISTI HUTAMI Wonosobo, 29 Juni 1996 S1 Keperawatan Ners Sukoharjo Wonosobo Purwokerto Gedangan RT 03 RW 06 Poltekkes Kemenkes 2 RUMANTI PUJI PANGESTUTI Semarang, 29 Juli 1997 S1 Keperawatan Ners Pecekelan Sapuran Wonosobo Surakarta Krajan Tempursari Sapuran Universitas Muhammadiyah 3 ZULYANI Wonosobo, 7 Juli 1994 S1 Keperawatan Ners Wonosobo Yogyakarta Kembaran RT 03 RW 02 Universitas Harapan Bangsa 4 TRI ADINING CAHYO Wonosobo, 11 Maret 1996 S1 Keperawatan Ners Kalikajar Wonosobo Purwokerto Wonosari Rt 03/Rw 09.Kejajar, Universitas Harapan Bangsa 5 NOVIKA ADIYANI Wonosobo, 19 November 1996 S1 Keperawatan Ners Wonosobo Purwokerto Adipasir Rt 01 / Rw 05, Kec. Universitas Muhammadiyah 6 YULI RATNASARI Banjarnegara, 16 Juli 1997 S1 Keperawatan Ners Rakit, Kab. Banjarnegara Purwokerto Karangkidul RT 02 RW 05 STIKES Guna Bangsa 7 UBAIDILLAH Magelang, 23 Juli 1995 S1 Keperawatan Ners Rejowinangun Magelang Yogyakarka Sambon Sumberdalem RT 07 Universitas Muhammadiyah 8 ALUAN TANJUNG Wonosobo, 5 September 1995 S1 Keperawatan Ners RW 06 Kertek Wonosobo Magelang Mangunsari RT 01 RW 04 Universitas Respati 9 MURNIYATI ASTUTI Wonosobo, 11 September 1996 S1 Keperawatan Ners Sapuran Wonosobo Yogyakarta Selamaya RT 03 RW 06 Gunung Universitas Muhammadiyah 10 RITA KURNIATI Wonosobo, 3 Mei 1996 S1 Keperawatan Ners tugel Sukoharjo Wonosobo Yogyakarta Kepakisan RT 02 RW 04 Batur Universitas Muhammadiyah -

Earthquake Statistics - 5,536 - 5,782 Killed Indonesia: Earthquake and 36,457 - 57,790 Injured.”

"The Govenrment is revising earthquake statistics - 5,536 - 5,782 killed Indonesia: Earthquake and 36,457 - 57,790 injured.” OCHA Situation Report No. 10 OCHA Situation Report Issued 05 June 2006 GLIDE: EQ-2006-000064-IDN Number of killed and injured IDP’s needs in Boyolali: SITUATION District breakdown (as of 30 May) - 200 family tents Number of aftershocks declining. Mt Merapi continues to erupt with partial - 200 family kits collapse of lava dome at summit. Eruptions producing avalanches of hot IDP’s needs in Klaten: - 5 platoon tents gas and volcanic material. BAPPENAS carrying out earthquake damage - basic medicines (analgesic, antibiotic, - baby food & milk and loss assessment that is to be completed by 14 June. Followed by antibiretic) - field kitchen equipment - paramedics - 5 generators Government action plan. INDONESIA - logistics (ambulances, communication - 125 blankets ACTION devices/handy talky for 12 community IDP’s needs in Sleman: - 200 pallets Government of Japan announced grant of USD 4M to Indonesian - medical teams health centres) - light device Jakarta Government and USD 1M to IFRC. Ministry of Health continues to provide - water and sanitation - masks - volunteer - mineral water - eye drops - motorbike for assessment free medical treatment in state-owned and private hospitals. Measles - six platoon tents - sugar - car for distribution and mobilization vaccination and Vitamin A supplement campaign to begin this week. Early - food items for 1,252 persons - rain coats warning system for disease surveillance established. Agencies working on - medicine - 300 family tents water and sanitation assessment. CARDI to construct 100 communal - baby milk latrines, distribute 400 shelter recovery kits and 1,000 household kits. -

75 Lampiran Tabulasi Ukuran Pemerintah Daerah

75 LAMPIRAN TABULASI UKURAN PEMERINTAH DAERAH Kab/Kota Tahun Asset LN ASET Banjar 26.940 negara 2015 3773105046825 Banyumas 2015 4996293115180 25.910 Batang 2015 2125178027710 28.780 Blora 2015 2200545645447 26.290 boyolali 2015 2362547346330 26.430 Brebes 2015 2504881095295 26.740 cilacap 2015 4101272249790 26.260 Demak 2015 2797430244005 26.330 Grobogan 2015 2110181560904 26.320 Jepara 2015 5227429224883 26.270 Karanganyar 2015 2639214244404 26.200 kendal 2015 2558870403771 26.230 Kebumen 2015 3910364384327 25.970 Klaten 2015 2912320354217 26.270 Kudus 2015 3164989044015 26.290 magelang 2015 2889293466866 26.460 Pati 2015 4058238306203 26.250 Pekalongan 2015 2176088770014 26.160 Pemalang 2015 2711229161504 26.100 Purbalingga 2015 1947434687329 26.180 Purworejo 2015 1988247880169 25.990 rembang 2015 1632557326614 26.350 semarang 2015 2614285239513 26.310 sragen 2015 2351849252835 26.470 sukoharjo 2015 3551142341578 26.030 temanggung 2015 2608342350120 26.080 wonogiri 2015 2773957987499 25.930 wonosobo 2015 1618325931484 26.440 Tegal 2015 258256911143 26.950 kot 25.750 magelang 2015 2186014334170 kot 25.840 pekalongan 2015 1893808840397 kot salatiga 2015 1695025718315 27.810 76 kot 26.640 semarang 2015 23210940494528 kot 26.330 surakarta 2015 7058634910205 Kota Tegal 2015 1830740165647 27.590 Banjar 28.960 negara 2016 3764999667285 Banyumas 2016 512213981696 26.960 Batang 2016 2340793700282 28.480 Blora 2016 2324010734307 28.470 boyolali 2016 2611631303909 28.590 Brebes 2016 2792866204611 28.660 cilacap 2016 4019210952136 29.020 Demak -

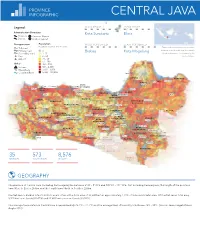

Central Java

PROVINCE INFOGRAPHIC CENTRAL JAVA Legend: MOST DENSE LEAST DENSE Administrative Boundary Kota Surakarta Blora Province Province Capital District District Capital Transportation Population MOST POPULATED LEAST POPULATED Population counts at 1km resolution Toll road The boundaries and names shown and the Primary road 0 Brebes Kota Magelang designations used on this map do not imply Secondary road 1 - 5 official endorsement or acceptance by the Port 6 - 25 United Nations. Airport 26 - 50 51 - 100 Other 101 - 500 INDRAMAYVolcanoU 501 - 2,500 Water/Lake 2,501 - 5,000 Coastline/River 5,000 - 130,000 Jepara Cirebon JEPARA REMBA NG Rembang KOTA Pati PATI KUDUS CIREBON Kudus CIREBON KOTA Tegal Pemalang PEKALON GAN Brebes KOTA Kendal Demak TEGAL Pekalongan TUB AN Semarang DEMAK KEND AL Slawi Batang Semarang Blora KUNINGAN KOTA SEMA RANG Kajen BATANG TEGAL Purwodadi PEMA LAN G GROBOGA N BOYOLALI PEKALON GAN Ungaran Ungaran Dieng Volc Complex BREB ES Slamet TEMA NGGUN G SEMA RANG BLORA BOJONEGO RO PURB ALINGGA Sundoro Salatiga KOTA BANJARN EGARA Wonosobo Temanggung KOTA BANJAR BANYUMAS Banjarnegara Sumbing Banjar TelomoyoSALATIGA SRAGEN NGAWI Purbalingga KOTA Purwokerto WONO SOBO Sragen Ngawi MA GELANG Merbabu Magelang Boyolali Surakarta MA GELANG Merapi KOTA CIAMIS KEBU MEN Mungkid Caruban SURAKARTA Karanganyar Madiun KOTA MA DIU N CILACAP Lawu Kebumen SUKO HARJO Magetan Purworejo SLEMAN Klaten MA DIU N Parigi Sukoharjo KARANGANYAR MAGETAN Cilacap KOTA Sleman PURWOREJO KLATEN NGANJUK YOGYAKARTA Yogyakarta Wonogiri Wates Yogyakarta KULON Ponorogo Bantul PROGO WONO GIRI PONOROGO BANTUL 35 573 8,576 Wonosari DISTRICTS SUB-DISTRICTS VILLAGES GUNUN G Trenggalek KIDU L PACITAN Pacitan TRENGGALEK TULUNGA GUNG GEOGRAPHY The province of Central Java (including Karimunjawa) lies between 5°40' - 8°30'S and 108°30' - 111°30'E. -

Mints Misr National Itinerary Transport Study

MiNTS Misr National Itinerary Transport Study Counterpart Training Program Stage 1 – Knowledge Building Stage Day 2 - Session 1 1 MiNTS Misr National What’s GIS? Transport Study • Geographic Information System (GIS) is “a computer application used to store, view, and analyze geographical information, especially maps”. 2 (Source: American Heritage Dictionary) A1-60 1 MiNTS Misr National Layer and Dataset Transport Study There are various geographic features such as administrative boundary, transportation, land use, census result, structures and so force. Data types are also various including numerical results of mapping survey, photo image, address and zip code. GIS relate all these data and enable cross-layer analysis on computer. 3 MiNTSAdvantages of GIS compared with Misr National Transport Study Paper Map GIS is … • Multiscale – Zoom in and out freely • Interactive – Overlay function ease interactive analyses • Software with Many Applications – Tools such as map editing, geographical analyses, routing, geocoding etc • Multiple Source – Many kind of source of information can be • Flexible – A variety of GIS map applications and frameworks support a wide range of deployment options such as original software or website 4 A1-61 2 MiNTS Misr National 3 functions and views of GIS Transport Study • Geodatabase – A GIS is a spatial database containing datasets such as features, rasters, attributes, topologies, networks, and so forth. • Geoprocessing – A GIS is a set of intelligent maps and other views that show features and feature relationships on the earth’ s surface. • Geovisualization – A GIS is a set of information transformation tools that derive new information from existing datasets. 5 MiNTS Misr National Type of GIS dataset Transport Study • Vector data – ex. -

List Agen 201610.Xlsx

REGION KABUPATEN KECAMATAN KELURAHAN ALAMAT AGEN AGEN ID NAMA AGEN PIC AGEN JARINGAN KANTOR CENTRAL JAVA BANTUL BAMBANGLIPURO MULYODADI PAKER RT 004 213ED0107P000058 MAYLA CELL MARYADI BTPN PURNABAKTI BANTUL CENTRAL JAVA BANTUL BAMBANGLIPURO MULYODADI GAYAMAN KRATON RT 006 213ED0107P000026 MINIMIZE TRI MINTARJO BTPN PURNABAKTI BANTUL CENTRAL JAVA BANTUL BAMBANGLIPURO SIDOMULYO NGAMPELAN 213ED0107P000049 HT CELL SUTRININGSIH BTPN PURNABAKTI BANTUL CENTRAL JAVA BANTUL BAMBANGLIPURO SIDOMULYO JL. PAKER DAWETAN SIDOMULYO 213ED0106P000054 SUN STAR SUNU BADI BTPN PURNABAKTI BANTUL CENTRAL JAVA BANTUL BAMBANGLIPURO SIDOMULYO KARANGASEM DK VIII SELO RT 004 SIDOMULYO 213ED0107P000059 KIOS TANI MUDA RIZKY CAHYA PRATAMA BTPN PURNABAKTI BANTUL CENTRAL JAVA BANTUL BAMBANGLIPURO SIDOMULYO JALAN PARANGTRITIS SIDOMULYO 213ED0107P000022 FITRIA CELL HUSEIN ALKAF BTPN PURNABAKTI BANTUL CENTRAL JAVA BANTUL BAMBANGLIPURO SIDOMULYO TURI RT 004 213ED0107P000031 MOSA CELL TIWUK NURSANTI BTPN PURNABAKTI BANTUL CENTRAL JAVA BANTUL BAMBANGLIPURO SUMBERMULYO GANJURAN INDAH NO 25 RT 08 213ED0107P000018 LOJI CELL AGUS SANTOSO BTPN PURNABAKTI BANTUL CENTRAL JAVA BANTUL BAMBANGLIPURO SUMBERMULYO DERMAN GERSIK RT 006 213ED0107P000052 PASAR PULSA SRI UTAMI BTPN PURNABAKTI BANTUL CENTRAL JAVA BANTUL BAMBANGLIUPURO SIDOMULYO CUNGKUP RT1 213ED0106P000004 TOKO BU ETI ETI SUSANTI BTPN PURNABAKTI BANTUL CENTRAL JAVA BANTUL BAMBANGLIUPURO SIDOMULYO JL. SAMAS KM18 213ED0106P000007 WHYAND CELL WINI SUNARNININGSIH BTPN PURNABAKTI BANTUL CENTRAL JAVA BANTUL BANGUNTAPAN BANGUNTAPAN -

Feasibility Livestock of Broiler (Gallus Domesticus) in Wadaslintang District Subdistrict Wonosobo

Agroland: The Agriculture Science Journal, 2015 December 2(2) : 98– 101 ISSN : 2407 - 7585 E-ISSN : 2407 - 7593 FEASIBILITY LIVESTOCK OF BROILER (GALLUS DOMESTICUS) IN WADASLINTANG DISTRICT SUBDISTRICT WONOSOBO Zulfanita1), Uswatun Hasanah2), Hanung Dhidhik Arifin1) 1) Animal Husbandry Program Studies Agriculture Faculty. University Muhammadiyah Purworejo. E-mail: [email protected] 2) Agribusiness Program Studies Agriculture Faculty. University Muhammadiyah Purworejo ABSTRACT This study aims to determine : Feasibility of broiler farming in Wadaslintang District, the method basic was used in this research is survey method with the research location Wadaslintang District Subdistrict Wonosobo. Sampling technic was used 43 farmers. Based on the results that broiler farming in Wadaslintang the needed total average cost is Rp 8,927,929.77 average total revenue is Rp 20,653,290.70, the average income is Rp 13,487,185.60, an average profit is Rp 11,725,360.93. Rated R/C ratio is 2.31, productivity of capital π/C ratio is 131.33%, labor productivity Rp 544.223,71/HKO, farmer income is Rp 13,487,185.60 > land rent value is Rp 1,353 per production period 488,37, meat chiken production > BEP value of meat chiken production1744.54 > 403.00, Income > BEP value of income is 20,653,290.70 > Rp 4,759,218.42, meat prices > BEP prices Rp 11.838,77 > Rp 5.117,62, if the price decline is not exceed 56.78%, the farmers do not losses, its mean that broiler farming is feasible to grow up. Key Words : Broiler, feasibility, wadaslintang. INTRODUCTION chicken meat in 2011 reached 1.602.800 quintal in 2012. -

A Case Study of Five Villages in Central Java by Indra Krishnamurti, Arief Nugraha, Mercyta Jorsvinna Glorya

Optimizing The Use of Village Treasury Land: A Case Study of Five Villages in Central Java by Indra Krishnamurti, Arief Nugraha, Mercyta Jorsvinna Glorya Optimizing The Use of Village Treasury Land: A Case Study of Five Villages in Central Java Authors: Indra Krishnamurti Arief Nugraha Mercyta Jorsvinna Glorya Center for Indonesian Policy Studies (CIPS) Acknowledgement: We thank Kidung Asmara and Rusta Widjaja for asisting the research. Jakarta, Indonesia March, 2019 Copyrights © 2019 by Center for Indonesian Policy Studies EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Village treasury lands (tanah kas desa) originate from the colonial era and usually comprise a few hectares that remain under the control of the village government. Village Law No. 6/2014 allows villages to manage their own assets, including village treasury lands, for common welfare and the benefit of the most vulnerable groups of the village. Ministry of Home Affairs Regulation 1/2016 stipulates three relevant formats of village land use: rental, cooperation in joint ventures, and Build Operate Transfer/Build Transfer Operate (BOT/BTO). Land is a strategic resource on the Indonesian island of Java, which has a large rural population. The most common plot sizes for farmland are small and can hardly sustain the lives of their owners and are increasingly transformed to serve industrial and infrastructure purposes. For this reason, ensuring the optimal use of village treasury lands is an important policy objective. Sidomulyo and Bonorowo Villages in Kebumen District have applied the rental format for their village land and leased the land to poor farming households. Tlogojati and Beran Villages in Wonosobo District engaged in business cooperation, while villagers in Sukoharjo Village in Wonosobo District applied the BOT format when building and operating a local market.