Ivan Mazepa, Hetman of Ukraine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

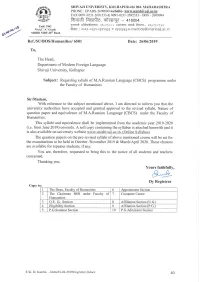

M.A. Russian 2019

************ B+ Accredited By NAAC Syllabus For Master of Arts (Part I and II) (Subject to the modifications to be made from time to time) Syllabus to be implemented from June 2019 onwards. 2 Shivaji University, Kolhapur Revised Syllabus For Master of Arts 1. TITLE : M.A. in Russian Language under the Faculty of Arts 2. YEAR OF IMPLEMENTATION: New Syllabus will be implemented from the academic year 2019-20 i.e. June 2019 onwards. 3. PREAMBLE:- 4. GENERAL OBJECTIVES OF THE COURSE: 1) To arrive at a high level competence in written and oral language skills. 2) To instill in the learner a critical appreciation of literary works. 3) To give the learners a wide spectrum of both theoretical and applied knowledge to equip them for professional exigencies. 4) To foster an intercultural dialogue by making the learner aware of both the source and the target culture. 5) To develop scientific thinking in the learners and prepare them for research. 6) To encourage an interdisciplinary approach for cross-pollination of ideas. 5. DURATION • The course shall be a full time course. • The duration of course shall be of Two years i.e. Four Semesters. 6. PATTERN:- Pattern of Examination will be Semester (Credit System). 7. FEE STRUCTURE:- (as applicable to regular course) i) Entrance Examination Fee (If applicable)- Rs -------------- (Not refundable) ii) Course Fee- Particulars Rupees Tuition Fee Rs. Laboratory Fee Rs. Semester fee- Per Total Rs. student Other fee will be applicable as per University rules/norms. 8. IMPLEMENTATION OF FEE STRUCTURE:- For Part I - From academic year 2019 onwards. -

The Annals of UVAN, Vol . V-VI, 1957, No. 4 (18)

THE ANNALS of the UKRAINIAN ACADEMY of Arts and Sciences in the U. S. V o l . V-VI 1957 No. 4 (18) -1, 2 (19-20) Special Issue A SURVEY OF UKRAINIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY by Dmytro Doroshenko Ukrainian Historiography 1917-1956 by Olexander Ohloblyn Published by THE UKRAINIAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN THE U.S., Inc. New York 1957 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE DMITRY CIZEVSKY Heidelberg University OLEKSANDER GRANOVSKY University of Minnesota ROMAN SMAL STOCKI Marquette University VOLODYMYR P. TIM OSHENKO Stanford University EDITOR MICHAEL VETUKHIV Columbia University The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U. S. are published quarterly by the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S., Inc. A Special issue will take place of 2 issues. All correspondence, orders, and remittances should be sent to The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U. S. ПУ2 W est 26th Street, New York 10, N . Y. PRICE OF THIS ISSUE: $6.00 ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION PRICE: $6.00 A special rate is offered to libraries and graduate and undergraduate students in the fields of Slavic studies. Copyright 1957, by the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S.} Inc. THE ANNALS OF THE UKRAINIAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN THE U.S., INC. S p e c i a l I s s u e CONTENTS Page P r e f a c e .......................................................................................... 9 A SURVEY OF UKRAINIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY by Dmytro Doroshenko In tr o d u c tio n ...............................................................................13 Ukrainian Chronicles; Chronicles from XI-XIII Centuries 21 “Lithuanian” or West Rus’ C h ro n ic le s................................31 Synodyky or Pom yannyky..........................................................34 National Movement in XVI-XVII Centuries and the Revival of Historical Tradition in Literature ......................... -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

The History of Ukraine Advisory Board

THE HISTORY OF UKRAINE ADVISORY BOARD John T. Alexander Professor of History and Russian and European Studies, University of Kansas Robert A. Divine George W. Littlefield Professor in American History Emeritus, University of Texas at Austin John V. Lombardi Professor of History, University of Florida THE HISTORY OF UKRAINE Paul Kubicek The Greenwood Histories of the Modern Nations Frank W. Thackeray and John E. Findling, Series Editors Greenwood Press Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kubicek, Paul. The history of Ukraine / Paul Kubicek. p. cm. — (The Greenwood histories of the modern nations, ISSN 1096 –2095) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978 – 0 –313 – 34920 –1 (alk. paper) 1. Ukraine —History. I. Title. DK508.51.K825 2008 947.7— dc22 2008026717 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2008 by Paul Kubicek All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2008026717 ISBN: 978– 0– 313 – 34920 –1 ISSN: 1096 –2905 First published in 2008 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48 –1984). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Every reasonable effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright materials in this book, but in some instances this has proven impossible. -

Parliamentary Coalition Collapses

INSIDE:• Profile: Oleksii Ivchenko, chair of Naftohaz — page 3. • Donetsk teen among winners of ballet competition — page 9. • A conversation with historian Roman Serbyn — page 13. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXXIVTHE UKRAINIANNo. 28 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JULY 9,W 2006 EEKLY$1/$2 in Ukraine World Cup soccer action Parliamentary coalition collapses Moroz and Azarov are candidates for Rada chair unites people of Ukraine by Zenon Zawada The Our Ukraine bloc had refused to Kyiv Press Bureau give the Socialists the Parliament chair- manship, which it wanted Mr. KYIV – Just two weeks after signing a Poroshenko to occupy in order to coun- parliamentary coalition pact with the Our terbalance Ms. Tymoshenko’s influence Ukraine and Yulia Tymoshenko blocs, as prime minister. Socialist Party of Ukraine leader Eventually, Mr. Moroz publicly relin- Oleksander Moroz betrayed his Orange quished his claim to the post. Revolution partners and formed a de His July 6 turnaround caused a schism facto union with the Party of the Regions within the ranks of his own party as and the Communist Party. National Deputy Yosyp Vinskyi Recognizing that he lacked enough announced he was resigning as the first votes, Our Ukraine National Deputy secretary of the party’s political council. Petro Poroshenko withdrew his candida- Mr. Moroz’s betrayal ruins the demo- cy for the Verkhovna Rada chair during cratic coalition and reveals his intention the Parliament’s July 6 session. to unite with the Party of the Regions, The Socialists then nominated Mr. Mr. Vinskyi alleged. -

Socialist Realism Seen in Maxim Gorky's Play The

SOCIALIST REALISM SEEN IN MAXIM GORKY’S PLAY THE LOWER DEPTHS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By AINUL LISA Student Number: 014214114 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2009 SOCIALIST REALISM SEEN IN MAXIM GORKY’S PLAY THE LOWER DEPTHS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By AINUL LISA Student Number: 014214114 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2009 i ii iii HHaappppiinneessss aallwwaayyss llooookkss ssmmaallll wwhhiillee yyoouu hhoolldd iitt iinn yyoouurr hhaannddss,, bbuutt lleett iitt ggoo,, aanndd yyoouu lleeaarrnn aatt oonnccee hhooww bbiigg aanndd pprreecciioouuss iitt iiss.. (Maxiim Gorky) iv Thiis Undergraduatte Thesiis iis dediicatted tto:: My Dear Mom and Dad,, My Belloved Brotther and Siistters.. v vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I would like to praise Allah SWT for the blessings during the long process of this undergraduate thesis writing. I would also like to thank my patient and supportive father and mother for upholding me, giving me adequate facilities all through my study, and encouragement during the writing of this undergraduate thesis, my brother and sisters, who are always there to listen to all of my problems. I am very grateful to my advisor Gabriel Fajar Sasmita Aji, S.S., M.Hum. for helping me doing my undergraduate thesis with his advice, guidance, and patience during the writing of my undergraduate thesis. My gratitude also goes to my co-advisor Dewi Widyastuti, S.Pd., M.Hum. -

Sof'ia Petrovna" Rewrites Maksim Gor'kii's "Mat"

Swarthmore College Works Russian Faculty Works Russian 2008 "Mother", As Forebear: How Lidiia Chukovskaia's "Sof'ia Petrovna" Rewrites Maksim Gor'kii's "Mat" Sibelan E.S. Forrester Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-russian Part of the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Sibelan E.S. Forrester. (2008). ""Mother", As Forebear: How Lidiia Chukovskaia's "Sof'ia Petrovna" Rewrites Maksim Gor'kii's "Mat"". American Contributions to the 14th International Congress of Slavists: Ohrid 2008. Volume 2, 51-67. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-russian/249 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Russian Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mother as Forebear: How Lidiia Chukovskaia’s Sof´ia Petrovna Rewrites Maksim Gor´kii’s Mat´* Sibelan E. S. Forrester Lidiia Chukovskaia’s novella Sof´ia Petrovna (henceforth abbreviated as SP) has gained a respectable place in the canon of primary sources used in the United States to teach about the Soviet period,1 though it may appear on history syllabi more often than in (occasional) courses on Russian women writers or (more common) surveys of Russian or Soviet literature. The tendency to read and use the work as a historical document begins with the author herself: Chukovskaia consistently emphasizes its value as a testimonial and its uniqueness as a snapshot of the years when it was writ- ten. -

ENDER's GAME by Orson Scott Card Chapter 1 -- Third

ENDER'S GAME by Orson Scott Card Chapter 1 -- Third "I've watched through his eyes, I've listened through his ears, and tell you he's the one. Or at least as close as we're going to get." "That's what you said about the brother." "The brother tested out impossible. For other reasons. Nothing to do with his ability." "Same with the sister. And there are doubts about him. He's too malleable. Too willing to submerge himself in someone else's will." "Not if the other person is his enemy." "So what do we do? Surround him with enemies all the time?" "If we have to." "I thought you said you liked this kid." "If the buggers get him, they'll make me look like his favorite uncle." "All right. We're saving the world, after all. Take him." *** The monitor lady smiled very nicely and tousled his hair and said, "Andrew, I suppose by now you're just absolutely sick of having that horrid monitor. Well, I have good news for you. That monitor is going to come out today. We're going to just take it right out, and it won't hurt a bit." Ender nodded. It was a lie, of course, that it wouldn't hurt a bit. But since adults always said it when it was going to hurt, he could count on that statement as an accurate prediction of the future. Sometimes lies were more dependable than the truth. "So if you'll just come over here, Andrew, just sit right up here on the examining table. -

Sustainable Development of Obolon Corporation Official Report

2013–2014 Sustainable Development of Obolon Corporation official report © Obolon Corporation, 2014 1 CONTENTS CORPORATION PRODUCTION PEOPLE 2 Appeal from the President 29 Production Facilities Structure 46 Working Environment 3 Social Mission 36 Brand portfolio 51 Life and Health 5 Reputation 39 Quality Management 54 Ethics and Equal Rights 7 Business Operations Standards 44 Innovations 56 Personnel Development 10 Corporate Structure 45 Technologies 58 Incentives and Motivation 18 Corporate Management 21 Stakeholders ECONOMICS ENVIRONMENT SOCIETY 60 Financial and Economic Results 69 Efficient Use of Resources 74 Development of Regions 62 Production Indicators 72 Wasteless Production 87 Promotion of Sports 63 Efficient Activity 90 Educational Projects 66 Risks 92 Sponsorship and Volunteering 96 Report overview 97 Sustainable development plans 99 Contacts 100 GRI © Obolon Corporation, 2014 SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF OBOLON CORPORATION OFFICIAL REPORT 2013/14 2 CORPORATION APPEAL FROM THE PRESIDENT Dear Partners, I am pleased to present Obolon Corporation's sixth Sustainability Report. This document summarizes the company's information on all socially important initiatives in the eight regions of Ukraine and presents the corporation's specific achievements in raising community life quality, minimizing environment impact, and improving employment practices over the year 2013 and the first half of 2014. This year's report is the first one to demonstrate the social, environmental and economic impact of Obolon Corporation in the regions where its facilities are located. Since the publication of the first Non-Financial Report, the Obolon Corporation has made significant progress on its way to sustainability. The commitment of our employees, implementation of several products and organizational innovations, as well as significant reduction of its environmental impact allowed the Corporation reinforce its status as a reliable and responsible member of the Ukrainian community and strengthen its market positions. -

NARRATING the NATIONAL FUTURE: the COSSACKS in UKRAINIAN and RUSSIAN ROMANTIC LITERATURE by ANNA KOVALCHUK a DISSERTATION Prese

NARRATING THE NATIONAL FUTURE: THE COSSACKS IN UKRAINIAN AND RUSSIAN ROMANTIC LITERATURE by ANNA KOVALCHUK A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Comparative Literature and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2017 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Anna Kovalchuk Title: Narrating the National Future: The Cossacks in Ukrainian and Russian Romantic Literature This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Comparative Literature by: Katya Hokanson Chairperson Michael Allan Core Member Serhii Plokhii Core Member Jenifer Presto Core Member Julie Hessler Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2017 ii © 2017 Anna Kovalchuk iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Anna Kovalchuk Doctor of Philosophy Department of Comparative Literature June 2017 Title: Narrating the National Future: The Cossacks in Ukrainian and Russian Romantic Literature This dissertation investigates nineteenth-century narrative representations of the Cossacks—multi-ethnic warrior communities from the historical borderlands of empire, known for military strength, pillage, and revelry—as contested historical figures in modern identity politics. Rather than projecting today’s political borders into the past and proceeding from the claim that the Cossacks are either Russian or Ukrainian, this comparative project analyzes the nineteenth-century narratives that transform pre- national Cossack history into national patrimony. Following the Romantic era debates about national identity in the Russian empire, during which the Cossacks become part of both Ukrainian and Russian national self-definition, this dissertation focuses on the role of historical narrative in these burgeoning political projects. -

TRANSLATION QUALITY ASSESSMENT at the CROSSROADS of ETHNOLINGUISTICS and ETHNOGRAPHY Taras Shevchenko’S Irzhavets in English Translations

ISSN 2029-7033. VERTIMO STUDIJOS. 2014. 7 TRANSLATION qUALITY ASSESSMENT AT THE CROSSROADS OF ETHNOLINGUISTICS AND ETHNOGRAPHY Taras Shevchenko’S Irzhavets IN ENGLISH Translations Taras Shmiher Faculty of Foreign Languages Ivan Franko National University in L’viv, Ukraine [email protected] Ethnographic approaches to understanding a text and its cultural values have been scarcely developed from the viewpoint of linguistic verification in translation criticism. Methods of studying cultural material which focus on the environment and behaviour can be borrowed from Ethnography for identifying and assessing cultural values in the texts of an original and a translation. The case study is performed on the key personality in Ukrainian cultural history, the poet, artist and thinker Taras Shevchenko (1814–1861) whose poetic texts turned out to be prophetical for constructing the Ukrainian political nation out of ethnic mass and building the future Ukrainian nation-state. ‘Translation is museum’ is no longer an eloquent metaphor, but a multi-layered concept in the system of text typology. The starting point for the ethnographic analysis of the original-translation relations is collective memory as a textual category. Close to intertextuality which is oriented toward a variety of existing and connected texts, collective memory enables one to focus on the selectiveness of cultural information as actualized – really or probably – in a newly generated text. Axiological values in the text should be interpreted via the symbolization of an event. This symbolization along with cultural compatibility, implications and misunderstandings offer a close set of criteria for textual comparisons. The finalized ethnographic system of contrasting an original and a translation contribute to the cultural interpretation of a text, so needed in translation criticism. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1939, No.42

www.ukrweekly.com ж ~??? -i iNo. 42 JERSEY GTFY, N. J., SATURDAY, (ХГГОВЙК 7, 1939 V5GHL. VH FIRST CALL FOR Ш*.А. UKRAINIANS AGAINST mSj< BASKETBALL |Д KREMLIN RULE YOUTH CLUB FORUMS The Ukrainian Naticmal.>Asapcja- An editorial on "Communist.Im-. Now is the time when many of our youth clubs are tion .will again sponsor basketball perialism" in the October 11, 1939 racking their collective heads in a painful4 effort to evolve during the coming season under issue of "The New Republic" ra the rules of the U.N.A.-basket-, dical weekly which in the past baa somfr manner of program for the coming -sear that will ball League, according to an an taken a pro-Soviet stand on many justify their existence. At first glance it would appear that nouncement issued this week by questions, declares that, YJt i» the problem is quite simple. But when one eliminates the Gregory Herman, Athletic Direc doubtful .whether the .-Polish Uk- tor of the U;N.A. rainjans, even the oppressed peas- usual dances and social affairs, that some opUn§|Bcally antsrwould iave^ chosen \4ttlb&- Financial assistance will be given ' governed from the Kremlin. They label as "activity," one inevitably finds the problem iamoy- to the teams that become mem may become reconciled, to Russian ingly. difficult. In АП attempt to be of some help to rthose bers of the. League, the announce ment states. Two trophies, it says, rule through hatred for the ,old faced with it, therefore, we offer a suggestion. will be awarded-to the winning Polish landowning class, v©r again Our suggestion, or, better still, recommendation, is teams:, one for the Eastern U.N.A.