A Study of Chen Cheng-Po's Sketchbooks: Visuals, Thoughts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modern Military Technology in Counterinsurgency Warfare: the Experience of the Nationalist Army During the Chinese Civil War

Modern Military Technology in Counterinsurgency Warfare: The Experience of the Nationalist Army during the Chinese Civil War Cheng, Victor 2007 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Cheng, V. (2007). Modern Military Technology in Counterinsurgency Warfare: The Experience of the Nationalist Army during the Chinese Civil War. (Working papers in contemporary Asian studies; No. 20). Centre for East and South-East Asian Studies, Lund University. http://www.ace.lu.se/upload/Syd_och_sydostasienstudier/pdf/Cheng.pdf Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Modern Military Technology in Counterinsurgency Warfare: The Experience of the Nationalist Army during the Chinese Civil War Victor Shiu Chiang Cheng* Working Paper No 20 2007 Centre for East and South-East Asian Studies Lund University, Sweden www.ace.lu.se * Victor S. -

Chen-Cheng Wang

Chen-cheng Wang Curriculum Vitae Fields of Study First field: East Asian history, modern Chinese history, political history Second field: World history Academic Research Interests The characteristics of the GMD and CCP political cultures and their influences on the two parties’ political capacities Education Ph.D. candidate in History, University of California, Irvine, June 2012 M.A. in History, National Taiwan University, 2006 B.A. in History, National Taiwan University, 2002 Publications Journal article, “Intellectuals and the One-party State in the Nationalist China: The Case of the Central Politics School (1927-1947),” In Modern Asian Studies, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming, 2014. Book review, “Ho-fung Hung, Protest with Chinese Characteristics: Demonstrations, Riots, and Petitions in the Mid-Qing Dynasty,” In Bulletin of the Institute of Modern History Academia Sinica. 76 (2012): 135-142. Book, Promoting Domestic Affairs Through Military Directives: The Role of Conscription in the KMT’s Strategies for and Praxis of State Building (1928-1945),Taipei: National Taiwan University Press, 2007.( 297 pages) Awards and Research Grants Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchang Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship, 2014 Institute of Modern History at the Academia Sinica Fellowship for Doctoral Candidates, 2014 University of California Irvine School of Humanities Summer Dissertation Fellowship, 2013 Henry Luce Foundation/ACLS Program in China Studies Pre-dissertation Grants for Research in China, 2013 University of California Irvine Teaching Assistantships (12-quarter guaranteed), 2010-13 University of California Irvine International Student Tuition Fellowship, 2009-11 University of California Regents’ Fellowship in the Humanities, 2009-10 Ministry of Education, Republic of China, National Study Abroad Scholarship, 2009-10 Chinese Development Fund Travel Research Grant, 2005 2. -

Chinese Civil War

asdf Chinese Civil War Chair: Sukrit S. Puri Crisis Director: Jingwen Guo Chinese Civil War PMUNC 2016 Contents Introduction: ……………………………………....……………..……..……3 The Chinese Civil War: ………………………….....……………..……..……6 Background of the Republic of China…………………………………….……………6 A Brief History of the Kuomintang (KMT) ………..……………………….…….……7 A Brief History of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)………...…………...…………8 The Nanjing (Nanking) Decade………….…………………….……………..………..10 Chinese Civil War (1927-37)…………………... ………………...…………….…..….11 Japanese Aggression………..…………….………………...…….……….….................14 The Xi’an Incident..............……………………………..……………………...…........15 Sino-Japanese War and WWII ………………………..……………………...…..........16 August 10, 1945 …………………...….…………………..……………………...…...17 Economic Issues………………………………………….……………………...…...18 Relations with the United States………………………..………………………...…...20 Relations with the USSR………………………..………………………………...…...21 Positions: …………………………….………….....……………..……..……4 2 Chinese Civil War PMUNC 2016 Introduction On October 1, 1949, Chairman Mao Zedong stood atop the Gates of Heavenly Peace, and proclaimed the creation of the People’s Republic of China. Zhongguo -- the cradle of civilization – had finally achieved a modicum of stability after a century of chaotic lawlessness and brutality, marred by foreign intervention, occupation, and two civil wars. But it could have been different. Instead of the communist Chairman Mao ushering in the dictatorship of the people, it could have been the Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, of the Nationalist -

The Present Situation and Our Tasks

1947 Speeches/Documents Title: THE PRESENT SITUATION AND OUR TASKS Author: Mao Zedong Date: December 25, Source:. SWM IV pp. 157-176 1947 Description:. THE PRESENT SITUATION AND OUR TASKS [This report was made by Comrade Mao Tse-tung to a meeting of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China held on December 25-28 1947, at Yangchiakou, Michih County, northern Shensi. In addition to those members and alternate members of the Central Committee able to attend, responsible comrades of the Shensi-Kansu-Ningsia Border Region and the Shansi-Suiyuan Border Region were present. The meeting discussed and adopted this report and also another document written by Comrade Mao Tse-tung, "Some Points in Appraisal of the Present International Situation" (see pp. 87-88 of this volume). Concerning Comrade Mao Tse-tung's report, the decision adopted at the meeting stated, "This report is a programmatic document in the political, military and economic fields for the entire period of the overthrow of the reactionary Chiang Kai-shek ruling clique and of the founding of a new-democratic China. The whole Party and the whole army should carry on intensive education around, and strictly apply in practice, this document and, in connection with it, the documents published on October 10, 1947 [namely, 'Manifesto of the Chinese People's Liberation Army', 'Slogans of the Chinese People's Liberation Army', 'Instruction on the Reissue of the Three Main Rules of Discipline and the Eight Points for Attention', 'Outline Land Law of China' and 'Resolution of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on the Promulgation of the Outline Land Law of China']. -

The Relationship Between Chiang Kai-Shek and Chen Cheng in Taiwan As Appears from Chen Cheng's Diary

Chiang Kai-shek and His Time New Historical and Historiographical Perspectives edited by Laura De Giorgi and Guido Samarani The Relationship Between Chiang Kai-shek and Chen Cheng in Taiwan as Appears from Chen Cheng’s Diary Hongmin Chen (Zhejiang University, China) Abstract In recent year Chen Cheng’s personal diaries have been donated to the Academia Sinica’s Institute of Modern History. This is a very valuable source to study Chen Cheng’s personal history as a military and a politician, but also to gain a better understanding of the inner history of the Guo- mindang and its government and political dynamics before and after 1949. Using both Chen Cheng’ diary and Chiang Kai-shek’s diary, this paper investigates the relationship between Chen and Chiang Kai-shek in Taiwan as transpires from these documents. It focuses on some key moments of their rela- tionship in the after-1949 period, as the first month after the Guomindang’s retreat to Taiwan, and the span of time between 1958 and 1961, just before Chen Cheng’s withdrawal from the political scene. Summary 1 A General Introduction to Chen Cheng’s Diary. – 2 Chen Cheng’s Questioning of Chiang’s Capacities After the Withdrawal to Taiwan. – 3 The 1958, Divergence of Opinion Regarding Chen Cheng’s ‘Cabinet Reorganization’. – 4 Chen Cheng’s 1960 “Trip to Jinmen”. – 5 The 1961 “Caoshan Controversy”. Keywords Diary of Chen Cheng. Chen Cheng. Chiang Kai-shek. Taiwan Years. In recent years, the opening of the Chen Cheng Archives at the Academia Historica in Taibei (officially “Vice President Chen Cheng Heritage”) and the publication of Chen Cheng’s memoirs, letters and other historical ma- terials concerning him have made the study of Chen Cheng and of the history of the Republic of China and of contemporary Taiwan much easier. -

Guide to Material at the LBJ Library Pertaining to China, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Korea

LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON L I B R A R Y & M U S E U M www.lbjlibrary.org June 2009 CO 50 CO 50-1 CO 50-2, CO 112 CO 151 MATERIAL AT THE LBJ LIBRARY PERTAINING TO CHINA, TAIWAN, HONG KONG, SOUTH KOREA AND NORTH KOREA INTRODUCTION This list includes the principal files in the LBJ Library that contain material on China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, South Korea and North Korea. It is not definitive, however, and researchers should consult with an archivist about other potentially useful files. For additional material on these countries, see also the Library's guide entitled, "Foreign Economic Policy During the Johnson Presidency: Foreign Aid, Food for Peace and Third World Economic Development (Asia, Africa, and Latin America)" (CO 1-8, CO 121, FG 105-4, FO 3, FO 3-2, IT 80, PC 2). Those files listed below that are marked with two asterisks (**) are unprocessed and are not currently available for research. In many folder titles noted below, the term "China" is used to mean Taiwan. Unless otherwise noted, the term "Korea" refers to South Korea. Material concerning the Asian Development Bank and the Manila Conference concerns South Korea. Material on the Pueblo (the United States naval vessel seized by the North Koreans on January 23, 1968) concerns North Korea. NATIONAL SECURITY FILE (NSF) This file was the working file of President Johnson's special assistants for national security affairs, McGeorge Bundy and Walt W. Rostow. Documents in the file originated in the offices of Bundy and Rostow and their staffs, in the various executive departments and agencies, especially those having to do with foreign affairs and national defense, and in diplomatic and military posts around the world. -

1 CHRISTINA WEI-‐SZU BURKE MATHISON the Ohio State University 217 Pomerene Ha

Christina Burke Mathison-CV CHRISTINA WEI-SZU BURKE MATHISON The Ohio State University 217 Pomerene Hall, 309B 1760 Neil Ave ColumBus, OH 43210 [email protected] 614.209.2382 (c) 614.688.8178 (o) EDUCATION The Ohio State University Columbus, OH Ph.D. Chinese Art History, 2013 Advisor: Dr. Julia F. Andrews Dissertation: “Identity, Modernity and Occupation: The Colonial Style of Taiwanese Painter Chen ChengBo (1895-1947)” The Ohio State University Columbus, OH M.A. Chinese Art History, 2005 Michigan State University East Lansing, Michigan B.A. Chinese Language, 2002 B.A. History of Art, 2002 East Asian Studies Specialization National Taiwan Normal University Taipei, Taiwan Certificate of Study, Chinese Language Studies, 2001 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Lecturer, The Ohio State University, ColumBus, Ohio, 2013-Present Graduate Research Associate, Wexner Center for the Arts, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, 2007-2011 Graduate Teaching Associate, The Ohio State University, ColumBus, Ohio, 2003-2007 Intern, Cincinnati Art Museum, Curatorial Department, 2006 PUBLICATIONS “World Coordinates” for the exhiBition, A Cultural Pioneer in East Asia: A 120-Year Anniversary Celebration of Chen Cheng-po, January 2014. “Identity, Hybridity, and Modernity: The Colonial Paintings of Chen Cheng-po” (認同, 混雜,現代性:陳澄波曰據時期的繪畫) in the exhiBition catalogue, 行過江南-陳澄波 藝術探索歷程 (Xingguo jiangnan-Chen Chengbo yishu tansuo licheng) Journey Through Jiangnan: A Pivotal Moment in Chen Cheng-po’s Artistic Quest, Taipei: Taipei Fine Arts Museum, March 2012. 1 Christina Burke Mathison-CV “Transnational Cultures, Hybrid Identities” in the exhiBition catalogue, (陽光下-陳澄 波個展, translated: Under the Searing Sun-A Solo Exhibition by Chen Cheng-po) Taipei: Taiwan Soka Association, March 2012. -

Newspaper and Television Advertising in 2004 Taiwan Presidential Election Christian Schafferer

Newspaper and Television Advertising in 2004 Taiwan Presidential Election Christian Schafferer Please note: This is a draft only At the end of the 20th century, political marketing appeared to have become a global phenomenon with more and more election campaigns resembling those of the US. Comparative research by Bowler (1992), Farrell (1996), Butler (1992) and others has shown the existence of a so-called ‘Americanization’ of election campaign practices in other democracies. This globalization of campaigning that can be best described as media and money driven has not only affected traditional democracies but also democracies of the Third Wave. The reason behind this worldwide proliferation of US campaigning is partly seen as the result of a modernization process and partly considered as a consequence of a transnational diffusion and implementation of US concepts and strategies of electoral campaigning. Modernization theorists claim that structural changes at the macro-level (changing media, political and social structure) has caused adaptive behavior at the micro level (parties, candidates, and journalists). Supporters of the transnational diffusion theory, however, focus “on the micro-level of entrepreneurial actors, exporting their strategic know-how to foreign contexts by supply- or demand- driven consultancy activities, thus changing and modifying the campaign practice in the respective countries.” (Plasser 2002, p.17). Observations on developments in East Asia suggest that any change in electoral campaigning has had its roots in both the macro and micro level, and its boundaries are set by institutional, legal, and social factors (Schafferer, forthcoming). As to Taiwan, the lifting of martial law in 1987 paved the way for a new era of election campaigning. -

CHINA February 1963–1966 Part 1: Political, Governmental, and National Defense Affairs

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Confidential U.S. State Department Central Files CHINA February 1963–1966 Part 1: Political, Governmental, and National Defense Affairs A UPA Collection from Confidential U.S. State Department Central Files CHINA February 1963–1966 PART 1: POLITICAL, GOVERNMENTAL, AND NATIONAL DEFENSE AFFAIRS Subject-Numeric Categories: AID, CSM, DEF, and POL Project Coordinator Robert E. Lester Guide compiled by Justin Owen Short A UPA Collection from 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Confidential U.S. State Department central files. China, February 1963–1966 [microform] : subject-numeric categories: AID, CSM, DEF, and POL / project coordinator, Robert E. Lester. microfilm reels. Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Justin Owen Short. Contents: pt. 1. Political, governmental, and national defense affairs ISBN 1-55655-838-4 (pt. 1) 1. China—Politics and government—1949–1976—Sources. 2. China—Economic conditions—1949–1976—Sources. 3. China—Foreign relations—United States. 4. United States—Foreign relations—China. 5. China—Foreign relations—1949–1976—Sources. 6. United States. Dept. of State—Archives. I. Title: Confidential US State Department central files. China, February 1963–1966. II. Title: China, February 1963–1966. III. Lester, Robert. IV. Short, Justin Owen. V. United States. Dept. of State. VI. University Publications of America (Firm) DS777.55 327.73051'09'46—dc22 2004048275 CIP The documents reproduced in this publication are among the records of the U.S. Department of State in the custody of the National Archives of the United States. No copyright is claimed in these official records. -

Intelligence Report Peking- Taipei Contacts: the Question

APPROVED FOR RELEASE ‘1 DATE: MAY 2007 f ,- 1 EO 12958 3.3(b) (1)>25Yrs EO 12958 3.3(b) (6)>25Yrs EO 12958 6.23~) DIRECTORATE OF INTELLIGENCE Intelligence Report Peking- Taipei Contacts: The Question of a Possible “Chinese Solutiotz ” (Rgerence Title.. POLO XLVI’ ‘ .... 7 -r .*. .a RSS.No. 0055/71 December 1971 WARNING ontains information affectin GIOUP 1 .. j. I. .. I I .. i ! This study concludes that no significant Nationalist vulnerabilities to proposed accommodation have developed to mid-1971, but that Peking's expectations and confidence in this regard are now almost certainly on the sharp rise. Indeed, a clear Nationalist interest in possible deals will probably soon begin to appear -- but still confined to in- dividuals. Beyond the near future, and especially as accumulated misfortune besets Nationalist leader- ship, such interest will doubtless grow. Whether it comes to be the policy of the Nationalist lead- ership depends on a myriad of forces, chief among them the Nationalist succession,, the effect of Taiwanese pressures, and, most importantly, the state of Nationalist confidence in outside guarantees of Taiwan's defense. Given a worst-case combination of such forces, susceptibilities to Peking will mount. Meanwhile, Peking will in any event grow more apprehensive that its Ta iwan ambit ions may be impeded by Taiwanese -- and Japanese -- aspirations. This study has profited .from constructive inputs fr,om many offices in the Central Tntelligence Agency. There is a sizable area of general agreement concerning- Nationalist-Communist contacts to date, but because so much of the evidence is tenuous, and the future necessarily speculative, the views expressed in this study remain essentially those df its principal author, Jerome W. -

1 in Dire Straits American Diplomacy and Export-Oriented Industrialization on Taiwan James Lee1 Ph.D. Candidate Department of Po

1 In Dire Straits American Diplomacy and Export-Oriented Industrialization on Taiwan James Lee1 Ph.D. Candidate Department of Politics Princeton University Draft. Please do not cite or circulate without the permission of the author. Abstract Scholars have pointed to the period 1958-1962 as marking Taiwan’s transition to export-oriented industrialization. Although the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) had traditionally favored protec- tionist trade policies and the dominance of state-owned enterprises, the KMT oversaw economic reforms beginning in the late 1950s that set Taiwan on the course of a capitalist and export-oriented development strategy. Previous studies have explained these reforms either as an internal decision of the Nationalist government or as the product of American coercion. Using historical case studies based on original archival research, I argue that the reforms reflected a U.S. diplomatic strategy of persuasion that altered the political balance between competing factions in the Nationalist eco- nomic bureaucracy. American officials claimed that a new development strategy would enable the party to pursue its core interests: an autonomous existence in the Cold War and the eventual reu- nification of China under Nationalist rule. These arguments created political support for a reform- oriented faction at the highest levels of the Nationalist leadership, ensuring a rapid transition to an outward-oriented development strategy. I conclude that the KMT’s decision to pursue export-ori- ented industrialization can only be understood at the intersection of domestic and international politics. 1 I would like to thank Christina Davis, Thomas Christensen, Helen Milner, Atul Kohli, Christopher Achen, Ethan Kapstein, Dalton Lin, Rory Truex, Keren Yarhi-milo, and Melissa Lee for their advice and guidance throughout the course of this research. -

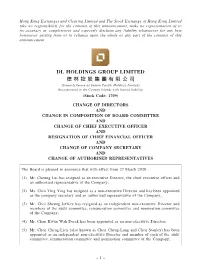

Change of Directors and Change in Composition of Board Committee and Change of Chief Executive Officer

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. DL HOLDINGS GROUP LIMITED 德 林 控 股 集 團 有 限 公 司 (formerly known as Season Pacific Holdings Limited) (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) (Stock Code: 1709) CHANGE OF DIRECTORS AND CHANGE IN COMPOSITION OF BOARD COMMITTEE AND CHANGE OF CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER AND RESIGNATION OF CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER AND CHANGE OF COMPANY SECRETARY AND CHANGE OF AUTHORISED REPRESENTATIVES The Board is pleased to announce that with effect from 27 March 2020: (1) Mr. Cheung Lui has resigned as an executive Director, the chief executive officer and an authorised representative of the Company; (2) Ms. Chin Ying Ying has resigned as a non-executive Director and has been appointed as the company secretary and an authorised representative of the Company; (3) Mr. Choi Sheung Jeffrey has resigned as an independent non-executive Director and members of the audit committee, remuneration committee and nomination committee of the Company; (4) Mr. Chan Kwun Wah Derek has been appointed as an non-executive Director; (5) Mr. Chen Cheng-Lien (also known as Chen Cheng-Lang and Chen Stanley) has been appointed as an independent non-executive Director and member of each of the audit committee, remuneration committee and nomination committee of the Company; – 1 – (6) Ms.