THE LONDON STONE: from MYTH and MYSTERY to CONTEMPORARY PLANNING Read by Alderman David Graves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

30 Eastcheap

30 EASTCHEAP LONDON EC3 30 EASTCHEAP 19,054 sq ft of new office space behind an impressive façade 30 EASTCHEAP 19,054 sq ft of new office space behind an impressive façade THREE A GRAND FAÇADE The Building 30 Eastcheap has a stately period façade with distinctive dome tower details to either end, framing the main structure. The stonework features elaborate details and gives the building it’s unique charm. FIVE KEY TRANSPORT LINKS ALL WITHIN A SHORT WALK Local Occupiers 1 1 ICBC 2 Berwin Leighton Paisner 20 3 Royal London Group 4 Allianz 2 3 13 5 Clarksons Local Landmarks 6 Hyperion Group 12 11 Surrounded on all sides by the City’s most iconic 7 Accenture 4 7 8 architectural landmarks, 30 Eastcheap couldn’t be 1 8 Chaucer Insurance 5 9 situated better for walking access to all the 3 City has to offer. 9 Royal & Sun Alliance 14 10 15 10 Beazley Group 16 4 6 Transport & Amenities 18 11 Aviva 19 30 Eastcheap is 100m away from Monument Station 12 AIG (District & Circle lines) and close walking distance 17 to several other Underground (Bank, Cannon Street, 13 Mitsui Sumitomo 2 5 London Bridge) and Mainline Stations. (Fenchurch Street, 14 London Underwriting Centre Cannon Street, London Bridge). 15 DAC Beachcroft 16 Zurich 17 Marsh 18 Gen Re 19 Axa Insurance 20 ACE Insurance 6 - Barclays Cycle Dock LANDMARKS ON YOUR DOORSTEP 30 EASTCHEAP Fenchurch Cannon London Bank Street Street Monument Bridge Station Station Station Station Station 5 minutes 5 minutes 4 minutes 1 minutes 9 minutes 1 30 St Mary Axe walk 2 Lloyd’s Building 3 Willis Building walk walk 4 Monument walk 5 20 Fenchurch St. -

861 Sq Ft Headquarters Office Building Your Own Front Door

861 SQ FT HEADQUARTERS OFFICE BUILDING YOUR OWN FRONT DOOR This quite unique property forms part of the building known as Rotherwick House. The Curve comprises a self-contained building, part of which is Grade II Listed, which has been comprehensively refurbished to provide bright contemporary Grade A office space. The property — located immediately to the east of St Katharine’s Dock and adjoining Thomas More Square — benefits from the immediate area which boasts a wide variety of retail and restaurant facilities. SPECIFICATION • Self-contained building • Generous floor to ceiling heights • New fashionable refurbishment • Full-height windows • New air conditioning • Two entrances • Floor boxes • Grade II Listed building • LG7 lighting with indirect LED up-lighting • Fire and security system G R E A ET T THE TEA TRE E D S A BUILDING OL S T E R SHOREDITCH N S HOUSE OLD STREET T R E E T BOX PARK AD L RO NWEL SHOREDITCH CLERKE C I HIGH STREET T Y R G O O A S D W S F H A O E R L U A L R T AD T H I O R T R N A S STEPNEY D’ O O M AL G B N A GREEN P O D E D T H G O T O WHITECHAPEL A N N R R R O D BARBICAN W O CHANCERY E A FARRINGDON T N O LANE D T T E N H A E M C T N O C LBOR A D O HO M A IGH MOORGATE G B O H S R R U TOTTENHAM M L R LIVERPOOL P IC PE T LO E COURT ROAD NDON WA O K A LL R N R H STREET H C L C E E O S A I SPITALFIELDS I IT A A W B N H D L E W STE S R PNEY WAY T O J R U SALESFORCE A E HOLBORN B T D REE TOWER E ST N I D L XFOR E G T O W R E K G ES H ALDGATE I A H E N TE A O M LONDON MET. -

Post Office London Pub

1822 PUB POST OFFICE LONDON PUB PUBLICANS-continued. Lord Napier, Frederick Rix, 27 London fields, Mansion House, Percy IIamilton Gardner, 204 Metropolitan Tavern,Da.niel William Vousden-, Laurie Arms,Robert Tuck,1 Should ham street, Hackney NE Evelyn street, Deptford SE 95 Farringdon road E C &; Bryanston square W 32 Crawford place, - George IIenryStribling, 118 Great Church - John Mather Presley, 46 & 48 Kennington Tavern, Waiter Orchard1 79 West Edgware road W lane, llammersmith W park road S E bourne road N Leather Exchange Tavern, Mrs.Alois Pfeiffer, Lord Nelson, Mrs. Anne Elizabeth Da.vey, 1 Marion Arms, George Robert Jackson, 46 Middleton Arms, Frederick Longhurst, 14 Leather market, Bermondsey SE Manchester road, Poplar E Lansdowne road, Dalston NE Mansfield street, Kingsland road N E Lee Arms, Thomas William Savage, 27 Marl - William Hunter Gillingham, 17 Nelson Market House, Glaze Bros. Ltd. 9 Russell - William Joseph Young, 123 Queen's rood, borough road, Dalston N E street, City road E G street, Covent garden WC Dalston NE Leicester (The),Best's Brewery Co. Ltd.1 New - Charles Mackie Hurt, 18 Upper Charlton Market House Tavern, Ernest Hellard, Col Mildmay Park Tavern, James Palmer, 130 0oYPntry street W street, Fitzroy ~quare W umbia market, Columbia road E Ball's Pond road N Leigh Hoy, Jsph. Perkoff, 163 Hanbury st E - James Edwd. Marley, 386 Old Kent rd SE - Siduey Geo.Skepelhorn, 7 Finsbury mkt E C Milford Haven, John Wakely, 214 Cale Leighton Arms, Mrs. Ada Arnsby, 101 Breck - Albert Joseph Milton, 137 Trafalgar street, Market tavern, Ernest Percival Gladwin, 65 donian road N nock road N Walworth SE Brushfield street E Millwall Dock Hotel, Mrs. -

The Art of Living FACTSHEET OVERVIEW DEVELOPER

The Art of Living FACTSHEET OVERVIEW DEVELOPER .....................................................................................................................................ST GEORGE PLC One Location DEVELOPMENT ......................................................................................................................... ONE BLACKFRIARS ESTIMATED COMPLETION ...................................................................................................QUARTER 3 & 4, 2018 LOCAL AUTHORITY .............................................................................. LONDON BOROUGH OF SOUTHWARK (LBS) One Blackfriars is a modern and impressive sculptural addition to the skyline of London. TENURE ..........................................................................................................................................999-YEAR LEASE The building will offer buyers a truly luxurious lifestyle with spacious interiors and BUILDING WARRANTY ....................................................................................10-YEAR NHBC BUILD WARRANTY the very best views across the River Thames including the Houses of Parliament, SERVICE CHARGES ......................................... EST. £6.54 PER SQ.FT. PLUS CAR PARKING AT £1,009 PER ANNUM St Paul’s Cathedral, the City and beyond. CAR PARKING..........................CAR PARKING AT £100,000 FOR TWO AND THREE BEDROOM APARTMENTS ONLY LOCATION ........................................................... ONE BLACKFRIARS, 1-16 BLACKFRIARS ROAD, LONDON SE1 9PB SITE -

The Kensington Collection a Local Guide

LOCAL AREA GUIDE coNTEnts OVERVIEW PAGE 02 LOCATION PAGE 04 INDULGE PAGE 06 DRINK PAGE 16 DINE PAGE 24 CAFÉ PAGE 32 CULTURE PAGE 38 SHOP PAGE 46 RELAX PAGE 54 NATURE PAGE 60 EDUCATE PAGE 66 01 THE KENSINGTON COLLECTION A LOCAL GUIDE St Edward's Kensington Collection will offer a magnificent collection of apartments designed for the luxury London lifestyle. Located in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, one of London’s most prestigious neighbourhoods and the perfect address for enjoying London life to the upmost. Some of the Capital’s most famous cultural attractions, restaurants and bars are close at hand, as well as an array of luxury shops, parks and concert halls. With many options a short stroll away, Kensington is a truly desirable address from which to discover the very best of what London has to offer. This local guide is merely an introduction to the prestigious Kensington area, where there is always something new and interesting waiting to be revealed amongst the historical greats and local institutions. Royal Albert Hall 02 EPPING POTTERS 0 d BAR 0 MOOR PARK a 0 o 1 THEOBALDS R BRICKET WOOD A GROVE W l COMMON a a View t ey i t b l b W b i MONKS A a r n O m Hill R t LEAVESDEN 2 g WOOD d Far d f d Roa h 1 s o t ros A 3 AERODROME a y A 4 0 5 N o r 4 S or C 1 r a A lean 2 A t 121 E 1 1 d w o CREWS s d r H 1 g R HILL WALTHAM o R in R e RADLETT ne A s e CROSS y o K L A a n t a a n d b e d 1 l GARSTON A EPPING a o 2 A t 5 e R t 1 oor Lan FOREST 8 S n e r lsm No r l t h 8 A 1 0 u n W 0 B Mollison Av e a 5 A1055 s t 3 odridden -

City of London Large D1 Unit

AVAILABLE TO LET City of London Large D1 Unit 38 Lombard Street, London, Greater London EC3V 9BS City of London Large D1 Unit Description: Rent £80,000 per annum (Passing) The available accommodation comprises a D1 Chiropractic clinic on the ground and lower ground Est. S/C £29,486 per annum floors of this mixed use office building. The unit has been fully fitted as an operational D1 clinic and S/C Details Heating and A/C includes a large smart waiting room/reception, street included in SC access and multiple treatment rooms. The unit benefits from great natural light on the ground floor, Est. rates payable £28,969 per annum good ceiling heights and great exposure to the passing trade of this City of London location. The unit Building type Healthcare has been largely partitioned on the ground floor to create multiple treatment and office rooms with the Planning class D1 lower ground floor predominantly open planned, meaning that any ingoing D1 practice can easily tailor Size 2,335 Sq ft the space to their needs. Lease details An assignment of an Location: existing lease contracted The premises is situated centrally in the City of outside the security and London, moments away from the Walkie Talkie provisions of the Landlord and Tenant Act building and equidistant from from Bank and 1954, expiring 21st June Monument stations which are both a two minute walk 2029. The lease is away. Lombard Street acts as a busy thoroughfare subject to a tenant-only between Fenchurch Street and Bank, meaning that break clause and rent the unit enjoys a constant level of high footfall. -

2. the Statement of Significance Discloses That Reference Was First

IN THE CONSISTORY COURT OF THE DIOCESE OF LONDON RE: ST STEPHEN W ALBROOK Faculty Petition dated 1 May 2012 Faculty Ref: 2098 Proposed Disposal by sale of Benjamin West painting, 'Devout Men Taking the Body of St Stephen' JUDGMENT 1. By a petition dated 1 May 2012 the Priest-in-Charge and churchwardens of St Stephen Walbrook and St Swithin London Stone with St Benet Sherehog and St Mary Bothaw with St Lawrence Pountney seek a faculty to authorise: "the disposal by sale of a painting by Benjamin West depicting 'Devout Men taking the body ofSt Stephen'". The proposal has the unanimous support of the Parochial Church Council but it is not recommended by the Diocesan Advisory Committee. General citation took place between 15 March and 18 Apri12012 and no objections were received from parishioners or members of the public. No objections were received from English Heritage or the Local Planning Authority (who were both notified of the proposal). The Ancient Monument Society, although consulted and invited to attend the directions and subsequent hearings, indicated that it did not wish to be involved. Initially, the Church Buildings Council (CBC), having advised against the proposals and agreeing with the views of the DAC, stated that it would not wish formally to oppose the petition but it subsequently changed its mind and was given leave by me to become a Party Opponent out of time. The Georgian Group objected from the outset and, having initially indicated it wished to be a Party Opponent, subsequently agreed to its interests being represented at the hearing by the CBC. -

Case Study: Preparing for Major Changes

Case Study: Preparing for major changes Control Centre communications – August 2016 blockade Understanding the activities that took place managed by the Control Centre to provide communications in preparation for changes Background August 2016 saw a new phase of the Thameslink Programme begin, which resulted in significant, medium-term temporary changes (through to January 2018 in some cases) for Southeastern passengers including; • Most Charing Cross trains resumed stopping at London Bridge, except in the “contra-peak” directions during weekday peak periods • Cannon Street trains no longer stopped at London Bridge • Cannon Street was closed between 27 August 2016 and 1 September 2016 inclusive – this included three “normal” working days. Given the scale of the changes, Southeastern needed to ramp up their passenger communications. This case study document sets out the actions that needed to be carried out by the Information Team within the Kent Integrated Control Centre (KICC). Twitter - Example Regular tweets, no less than twice daily, to continue until the 1 September 2016, covering the key messages; - Major changes to London Bridge & Cannon Street services from August 2016 - We strongly recommend you consider changing your journey to work between 30 August 2016 until 1 September 2016 - Cannon Street trains will not stop at London Bridge from Friday 26 August until January 2018 - Most Charing Cross services will resume stopping at London Bridge from Monday 29 August 2016 - The changes to contra-peak services at London Bridge on weekdays from Tuesday 30 August (AM services away from London not calling at London Bridge in evening peak). All tweets should link to the dedicated page on the website: southeasternrailway.co.uk/august (example) OIS (Operations Information Screens) - Example Southeastern had a series of animated films to show on OIS and NOIS which were on display from the 8th July 2016. -

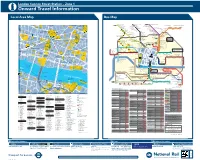

London Cannon Street Station – Zone 1 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

London Cannon Street Station – Zone 1 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map Palmers Green North Circular Road Friern Barnet Halliwick Park 149 S GRESHAM STREET 17 EDMONTON R 141 1111 Guildhall 32 Edmonton Green 65 Moorgate 12 A Liverpool Street St. Ethelburga’s Centre Wood Green I 43 Colney Hatch Lane Art Gallery R Dutch WALTHAMSTOW F for Reconcilation HACKNEY 10 Church E Upper Edmonton Angel Corner 16 N C A R E Y L A N E St. Lawrence 17 D I and Peace Muswell Hill Broadway Wood Green 33 R Mayor’s 3 T 55 ST. HELEN’S PLACE for Silver Street 4 A T K ING S ’S ARMS YARD Y Tower 42 Shopping City ANGEL COURT 15 T Jewry next WOOD Hackney Downs U Walthamstow E E & City 3 A S 6 A Highgate Bruce Grove RE 29 Guildhall U Amhurst Road Lea Bridge Central T of London O 1 E GUTTER LANE S H Turnpike Lane N St. Margaret G N D A Court Archway T 30 G E Tottenham Town Hall Hackney Central 6 R O L E S H GREEN TOTTENHAM E A M COLEMAN STREET K O S T 95 Lothbury 35 Clapton Leyton 48 R E R E E T O 26 123 S 36 for Whittington Hospital W E LOTHBURY R 42 T T 3 T T GREAT Seven Sisters Lea Bridge Baker’s Arms S T R E E St. Helen S S P ST. HELEN’S Mare Street Well Street O N G O T O T Harringay Green Lanes F L R D S M 28 60 5 O E 10 Roundabout I T H S T K 33 G M Bishopsgate 30 R E E T L R O E South Tottenham for London Fields I 17 H R O 17 Upper Holloway 44 T T T M 25 St. -

Qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwert Yuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiop

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertJune 20, 2014 yuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiop asdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzx MY SEARCH FOR THE ORIGINS OF cvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnDEACON JOHN DONE mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwePresented to The Doane Family Association Research Committee rtyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuio by pasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf Maureen Scott Committee Member ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklz 2014 xcvbnmqwertyuiop asdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyDuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopa sdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghj klzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcv bnmrtyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwert1 yuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiop June 20, 2014 Table of Contents Preamble:....................................................................................................pg. 3 Sections: 1 - The City of London and Its People..........................................................pg. 4 2 - City of London Pilgrims...........................................................................pg. .9 3 - PossiBle Links with Deacon John Done..................................................pg. 11 4 - Previous Lines of Inquiry........................................................................pg. 16 5 - Y-DNA Project.........................................................................................pg. 19 Summary / Recommendations:.................................................................pg. 20 References:................................................................................................pg. -

Governor's House

Finsbury Circus Liverpool St ALL LONDON W LOND ON W E ALL T A H G BE O Governor’s HouseR V U E IS N O T M D A A S O R D 5 Laurence Pountney Hill, London EC4R 0BR G K IT M S S C P H O United Kingdom H S I B Bank of Swiss Re England (The ‘Gherkin’) LEADENHALL ST C RNHILL O Ba nk L O M K B A Moorgate I R Liverpool St Aldgat e N D G S T W M I I C L N Mansion AN L FEN N I C T O ON S A HURCH S House T M R I S E T S Fenchurch St Cannon St EASTCHE AP TH G AM T ES S TO E T W G Monument E R D I ST Tower Hill R B K L OWER R TH A AM Adelaide House ES ST W H E Tower of T Custom House G U London Governor’s House D O I S 5 Laurence Pountney Hill R B LONDON EC4R 0BR N O D R IV N E R O T L HA M E S London Bridge Telephone By Underground S OUTHW ST +44 (0)20 3400 1000AR K The nearest underground station is Cannon Street (Circle and District The telephone switchboard is open between 0730 and 2200hrs, lines). Alternatively Bank (Central, Northern and Waterloo & City lines) is a Monday to Friday. In addition all solicitors have a DDI line with 5min walk away – use exit 6 for Lombard Street. -

Buses from Monument and Cannon Street

Buses from Monument and Cannon Street 43 141 21 149 55 towards Palmers Green towards Haggerston towards Friern Barnet Highbury & Islington towards Edmonton Geen Bus Station towards North Circular Road Newington Green Walthamstow Central Halliwick Park from stops M, Q from stops F, Q from stops F, Q from stops F, Q 149 55 Hackney Southgate Road Road Kingsland Road 17 Hoxton towards Archway Hoxton Baring Street Hoxton 43 21 141 55 Hackney Road Busesfrom stops MA, Q from Monument and CannonKingsland Road for Geffrye Museum Street Upper Street towards Oxford Circus Caledonian Road Islington Angel New North Road Shoreditch (not 55) King’s Cross Shoreditch for St. Pancras International City Road SHOREDITCH Town Hall 35 47 Moorelds Eye Hospital 43 141 Provost21 Street 149 from stops M, Q from stops55 M, Q towards Palmers Green towards 35 Haggerston towards Friern Barnet Highbury & Islington towards133 Edmonton344 Geen Bus Station towards MooreldsNorth Eye Circular43 Road Newington Green 47 Walthamstow Central Halliwick Park Hospital from from stops M, Q Bethnal Green Bethnal Green Eastman Q Dental Hospital from stops F, Q from stops F, Q Bank from stops F, City Road Old Street Threadneedle stops 149 Road Hackney F, Q from stops M, Q 55 388 Southgate Road Street Shoreditch Road towards Finsbury Square High Street 17 Kingsland Road Stratford City Bus Station 17 17 Moorgate Liverpool Hoxton towards Archway Hoxton Baring Street 133 55 Street Hoxton Hackney Road from stops M, Q 43 21 141 21 43 141 Kingsland Road for Geffrye Museum from stops MA, Q towards Upper Street Bus Station Liverpool Street Holborn Bank Princes Street Oxford Circus Bishopsgate Gray’s Inn Road Islington Angel New North Road Caledonian Road Circus On 12 October 2019 route 388 was St.