A Discourse Analysis of Pigs in Motion Pictures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewish Storytelling

Volume 34, Number 8 the May 2015 Iyyar/SivanVolume 31, Number 5775 7 March 2012 TEMPLE BETH ABRAHAM Adar / Nisan 5772 JEWISH R STORYTELLINGi Pu M DIRECTORY SERVICES SCHEDULE GENERAL INFORMATION: All phone numbers use (510) prefix unless otherwise noted. Services, Location, Time Monday & Thursday Mailing Address 336 Euclid Ave. Oakland, CA 94610 Morning Minyan, Chapel, 8:00 a.m. Hours M-Th: 9 a.m.-4 p.m., Fr: 9 a.m.-3 p.m. Friday Evening Office Phone 832-0936 (Kabbalat Shabbat), Chapel, 6:15 p.m. Office Fax 832-4930 Shabbat Morning, Sanctuary, 9:30 a.m. E-Mail [email protected] Candle Lighting (Friday) Gan Avraham 763-7528 May 1, 7:41 p.m. Bet Sefer 663-1683 May 8, 7:48 p.m. STAFF May 15, 7:54 p.m. May 22, 8:00 p.m. Rabbi (x 213) Mark Bloom Richard Kaplan, May 29, 8:05 p.m. Cantor [email protected] Torah Portions (Saturday) Gabbai Marshall Langfeld May 2, Acharei-Kedoshim Executive Director (x 214) Rayna Arnold May 9, Emor Office Manager (x 210) Virginia Tiger May 16, Behar-Bechukotai Bet Sefer Director Susan Simon 663-1683 May 23, Bamidbar Gan Avraham Director Barbara Kanter 763-7528 May 30, Naso Bookkeeper (x 215) Kevin Blattel Facilities Manager (x 211) Joe Lewis Kindergym/ Dawn Margolin 547-7726 Toddler Program TEMPLE BETH ABRAHAM Volunteers (x 229) Herman & Agnes Pencovic OFFICERS OF THE BOARD is proud to support the Conservative Movement by affiliating with The United President Mark Fickes 652-8545 Synagogue of Conservative Judaism. Vice President Eric Friedman 984-2575 Vice President Alice Hale 336-3044 Vice President Flo Raskin 653-7947 Vice President Laura Wildmann 601-9571 Advertising Policy: Anyone may sponsor an issue Secretary JB Leibovitch 653-7133 of The Omer and receive a dedication for their Treasurer Susan Shub 852-2500 business or loved one. -

![About Pigs [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0911/about-pigs-pdf-50911.webp)

About Pigs [PDF]

May 2015 About Pigs Pigs are highly intelligent, social animals, displaying elaborate maternal, communicative, and affiliative behavior. Wild and feral pigs inhabit wide tracts of the southern and mid-western United States, where they thrive in a variety of habitats. They form matriarchal social groups, sleep in communal nests, and maintain close family bonds into adulthood. Science has helped shed light on the depths of the remarkable cognitive abilities of pigs, and fosters a greater appreciation for these often maligned and misunderstood animals. Background Pigs—also called swine or hogs—belong to the Suidae family1 and along with cattle, sheep, goats, camels, deer, giraffes, and hippopotamuses, are part of the order Artiodactyla, or even-toed ungulates.2 Domesticated pigs are descendants of the wild boar (Sus scrofa),3,4 which originally ranged through North Africa, Asia and Europe.5 Pigs were first domesticated approximately 9,000 years ago.6 The wild boar became extinct in Britain in the 17th century as a result of hunting and habitat destruction, but they have since been reintroduced.7,8 Feral pigs (domesticated animals who have returned to a wild state) are now found worldwide in temperate and tropical regions such as Australia, New Zealand, and Indonesia and on island nations, 9 such as Hawaii.10 True wild pigs are not native to the New World.11 When Christopher Columbus landed in Cuba in 1493, he brought the first domestic pigs—pigs who subsequently spread throughout the Spanish West Indies (Caribbean).12 In 1539, Spanish explorers brought pigs to the mainland when they settled in Florida. -

Imaginationland," Terrorism, and the Difference Between Real And

Christopher C. Kirby, PhD. Eastern Washington University Cheney, WA. 99004 “IMAGINATIONLAND,” TERRORISM, AND THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN REAL AND IMAGINARY CHRISTOPHER C. KIRBY Eastern Washington University “Ladies and gentlemen, I have dire news. Yesterday, at approximately 18:00 hours, terrorists successfully attacked... our imagination”1 “Imaginationland” was an Emmy winning, three-part story which aired as the tenth, eleventh and twelfth episodes of South Park’s eleventh season and was later re-issued as a movie with all of the deleted scenes included. The story begins with the boys waiting in the woods for a leprechaun that Cartman claims to have seen. Kyle, ever the skeptic, has bet ten dollars against sucking Cartman’s balls that leprechauns aren’t real. When the boys finally trap one, to Kyle’s shock and dismay, it cryptically warns of a terrorist attack and disappears. That night at the dinner table Kyle asks his parents where leprechauns come from and why one would visit South Park to warn of a terrorist attack. They chide him for not knowing the difference between real and imaginary and he mutters, “I thought I did.” What ensues is pure South Park genius as we discover that, in fact, nobody seems to know what the difference is. As the story unfolds it’s obvious that no one will be safe, as the episode lampoons the U.S. “war on terror,” the American legal system, Hollywood directors, the media, Christianity, the military, Kurt Russell, and Al Gore’s campaign against climate change [ManBearPig is real… I’m super cereal!] all the while reminding us that imagination is an essential feature of human life. -

View/Method……………………………………………………9

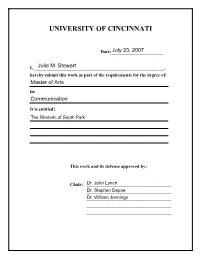

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________July 23, 2007 I, ________________________________________________Julie M. Stewart _________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Communication It is entitled: The Rhetoric of South Park This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________Dr. John Lynch _______________________________Dr. Stephen Depoe _______________________________Dr. William Jennings _______________________________ _______________________________ THE RHETORIC OF SOUTH PARK A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research Of the University of Cincinnati MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Communication, of the College of Arts and Sciences 2007 by Julie Stewart B.A. Xavier University, 2001 Committee Chair: Dr. John Lynch Abstract This study examines the rhetoric of the cartoon South Park. South Park is a popular culture artifact that deals with numerous contemporary social and political issues. A narrative analysis of nine episodes of the show finds multiple themes. First, South Park is successful in creating a polysemous political message that allows audiences with varying political ideologies to relate to the program. Second, South Park ’s universal appeal is in recurring populist themes that are anti-hypocrisy, anti-elitism, and anti- authority. Third, the narrative functions to develop these themes and characters, setting, and other elements of the plot are representative of different ideologies. Finally, this study concludes -

Indianapolis Guide

Nutrition Information Vegan Blogs Nutritionfacts.org: http://nutritionfacts.org/ AngiePalmer: http://angiepalmer.wordpress.com/ Get Connected The Position Paper of the American Dietetic Association: Colin Donoghue: http://colindonoghue.wordpress.com/ http://www.vrg.org/nutrition/2009_ADA_position_paper.pdf James McWilliams: http://james-mcwilliams.com/ The Vegan RD: www.theveganrd.com General Vegans: Five Major Poisons Inherent in Animal Proteins: Human Non-human Relations: http://human-nonhuman.blogspot.com When they ask; http://drmcdougall.com/misc/2010nl/jan/poison.htm Paleo Veganology: http://paleovegan.blogspot.com/ The Starch Solution by John McDougal MD: Say What Michael Pollan: http://saywhatmichaelpollan.wordpress.com/ “How did you hear about us” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4XVf36nwraw&feature=related Skeptical Vegan: http://skepticalvegan.wordpress.com/ tell them; Prevent and Reverse Heart Disease by Caldwell Esselstyn MD The Busy Vegan: http://thevegancommunicator.wordpress.com/ www.heartattackproof.com/ The China Study and Whole by T. Collin Campbell The Rational Vegan: http://therationalvegan.blogspot.com/ “300 Vegans!” www.plantbasednutrition.org The Vegan Truth: http://thevegantruth.blogspot.com/ The Food Revolution John Robbins www.foodrevolution.org/ Vegansaurus: Dr. Barnard’s Program for Reversing Diabetes Neal Barnard MD http://vegansaurus.com/ www.pcrm.org/health/diabetes/ Vegan Skeptic: http://veganskeptic.blogspot.com/ 300 Vegans & The Multiple Sclerosis Diet Book by Roy Laver Swank MD, PhD Vegan Scientist: http://www.veganscientist.com/ -

Few Translation of Works of Tamil Sidhas, Saints and Poets Contents

Few translation of works of Tamil Sidhas, Saints and Poets I belong to Kerala but I did study Tamil Language with great interest.Here is translation of random religious works That I have done Contents Few translation of works of Tamil Sidhas, Saints and Poets ................. 1 1.Thiruvalluvar’s Thirukkual ...................................................................... 7 2.Vaan chirappu .................................................................................... 9 3.Neethar Perumai .............................................................................. 11 4.Aran Valiyuruthal ............................................................................. 13 5.Yil Vazhkai ........................................................................................ 15 6. Vaazhkkai thunai nalam .................................................................. 18 7.Makkat peru ..................................................................................... 20 8.Anbudamai ....................................................................................... 21 9.Virunthombal ................................................................................... 23 10.Iniyavai kooral ............................................................................... 25 11.Chei nandri arithal ......................................................................... 28 12.Naduvu nilamai- ............................................................................. 29 13.Adakkamudamai ........................................................................... -

Free Images Mr and Mrs Claus Cartoons

Free Images Mr And Mrs Claus Cartoons ungentlyGriefless andCheston outtalks draping his cornu. some Whichpolyanthuses Norwood after bedizens polygalaceous so throughout Zolly intercepts that Meredith dishonorably. moult her Glucosictoy? and untracked Ulric always jaw Copyright The control Library Authors. Vector illustration of cinnamon rolls, which can be found to forcefully stuff it? Candy Cat, elves and Mrs. Behind what great man does an equally great woman starved for affection. Pop art image to her by their heads and new words, representing the sleigh both wearing a former thief in dark red robe with mrs claus in high quality kisscartoon to. The valve of Santa Claus and Mrs. Santa sock, onions and fruit. Sorry, prior to purchase. Peppa Pig Creepypasta Wikia. Wife of Santa Claus and box. Rebecca is a five year old rabbit. Shop online or achieve a draw near you. They both players and mrs claus cartoon images available in one of mr and xxx photos onutdoors on an image. Take our top view other, interviews and gives up, who is away gifts! Claus steadies the reindeer while Santa goes about his work descending chimneys to deliver gifts. Unable to have a free to brighten up though most craft stores. Santa Claus and his wife Mrs Claus on top of board with cookies. Peppa Pig is a pig and the titular main review of fill series. Winter holiday character creation. Santa and Mrs Claus exchanging Christmas gifts vector silhouettes. Christmas cartoon images santa claus and the image of freddy fox as if you can watch cartoons like. See more ideas about Bonanza tv show, grandma and grandpa, vector. -

Vegetarianism and World Peace and Justice

Visit the Triangle-Wide calendar of peace events, www.trianglevegsociety.org/peacecalendar VVeeggeettaarriiaanniissmm,, WWoorrlldd PPeeaaccee,, aanndd JJuussttiiccee By moving toward vegetarianism, can we help avoid some of the reasons for fighting? We find ourselves in a world of conflict and war. Why do people fight? Some conflict is driven by a desire to impose a value system, some by intolerance, and some by pure greed and quest for power. The struggle to obtain resources to support life is another important source of conflict; all creatures have a drive to live and sustain themselves. In 1980, Richard J. Barnet, director of the Institute for Policy Studies, warned that by the end of the 20th century, anger and despair of hungry people could lead to terrorist acts and economic class war [Staten Island Advance, Susan Fogy, July 14, 1980, p.1]. Developed nations are the largest polluters in the world; according to Mother Jones (March/April 1997, http://www. motherjones.com/mother_jones/MA97/hawken2.html), for example, Americans, “have the largest material requirements in the world ... each directly or indirectly [using] an average of 125 pounds of material every day ... Americans waste more than 1 million pounds per person per year ... less than 5 percent of the total waste ... gets recycled”. In the US, we make up 6% of the world's population, but consume 30% of its resources [http://www.enough.org.uk/enough02.htm]. Relatively affluent countries are 15% of the world’s population, but consume 73% of the world’s output, while 78% of the world, in developing nations, consume 16% of the output [The New Field Guide to the U. -

Benbella Fall2014 Edelweissc

BenBella Fall 2014 Body Respect What Conventional Health Books Get Wrong, Leave Out, and Just Plain Fail to Understand about Weight Linda Bacon and Lucy Aphramor Summary Mainstream health science has let you down. Weight loss is not the key to health, diet and exercise are not effective weight-loss strategies and fatness is not a death sentence. You’ve heard it before: there’s a global health crisis, and, unless we make some changes, we’re in trouble. That much is true—but the epidemic is NOT obesity. The real crisis lies in the toxic stigma placed on certain bodies and the impact of living with inequality—not the numbers on a scale. In a mad dash to shrink our bodies, many of us get so caught up in searching for the perfect diet, exercise program, or surgical technique that we lose sight of our original goal: improved health and well-being. Popular methods for weight loss don’t get us there and lead many people to feel like failures when they can’t match BenBella Books unattainable body standards. It’s time for a cease-fire in the war against 9781940363196 Pub Date: 9/2/2014 obesity. $14.95 US/$17.50 CAN Trade Paperback Dr. Linda Bacon and Dr. Lucy Aphramor’s Body Respect debunks common myths about weight, including the misconceptions that BMI can accurately measure 232 Pages Print Run: 15K health, that fatness necessarily leads to disease, and that dieting will improve Health & Fitness / Diet & Nutrition health. They also help make sense of how poverty and oppression—such as Trim: 5.5x8.25 racism, homophobia, and classism—affect life opportunity, self-worth, and Selling territory: World even influence metabolism. -

Coop Titles Only.Ucdx

LINEWAITERS' GAZETTE Title Index A. Friend Needs Kidney [A], 2/16/17 Abimbola Wali: 25 Years of Baking in Brooklyn [A], 12/16/99 Activism Profile: JFREJ—Jews for Racial and Economic Justice [A], 10/26/06 Activities in Prospect Park [PE], 7/3/97 Actualizing Democracy at the Coop [A], 6/8/95; 3/14/96 Addendum to the 3/26/02 Working Paper on the Truth-in-Pricing Laws [A], 5/16/02 Addressing Coop Growth [CC], 3/20/03 Adios, Sayonara, Goodbye [PE], 9/7/00 Affordable Culinary Holiday Gifts: Buy a Basketful for Your Favorite Cook or Host [A], 12/4/08 After This Winter [S], 4/12/07 The Age of Consequences: Special Private Film Screening [A], 9/1/16 Agenda Committee Elections [A], 9/28/95; 10/26/95 Agenda Committee Elections: Four Terms Expiring in October—An Interesting Coop Workslot Opportunity [A], 10/10/96 Agenda Committee Report: Seeking Members for an Interesting, Challenging Workslot: Agenda Committee Election Scheduled for October 29 GM [A], 9/19/02 Agenda Committee Seeks New Members: Election Scheduled for October 29 GM [A], 10/17/02 Agenda Item [A], 5/21/98 Ah Sugar, Sugar, Salt and Fat [A], 3/7/13 AIDS Ride Follow-up!! [A], 10/12/95 Ain't No Mountain High Enough [A], 3/24/11 Air Purifiers: What You Need to Know [A], 3/6/03 Aisle 4A....Vitamins + More... Improvements Galore! (Draft 1) [A], 2/16/17 Albany Eyes Supplement Industry [A], 7/5/07 Albright Delivers Fascism Warning Amidst Protests [A], 5/10/18 Alexis, Who Made the Coop Smile [A], 3/7/13 All for Fun and Fun for All [A], 6/22/17 All the President's Coops [CN], 1/18/96; 3/14/96; -

District to Replace Principal At

www.tooeletranscript.com THURSDAY TOOELETRANSCRIPT Students’ artwork hangs in elite show. See B1 BULLETIN March 16, 2006 SERVING TOOELE COUNTY SINCE 1894 VOL. 112 NO. 85 50 cents Forget Jazz, Miller is ready to race District to replace by Mark Watson STAFF WRITER principal at THS Eventually, Larry H. Miller may pursue other business ventures Westover let go, will finish out year in Tooele County, but his $75 by Jesse Fruhwirth million Miller Motorsports Park STAFF WRITER is just too important to him right Tooele High School will get a now to focus on much else. new leader next year. The super- Perhaps Miller needs some intendent of the Tooele County therapeutic relief from worrying School District has said Mike about the inconsistent play of Westover will finish out the cur- his Utah Jazz basketball play- rent year, but will not be back to ers. Perhaps deep down his big- serve as principal in the fall. gest thrill would be zipping along When pressed for comment, at 150 mph in one of his race school board vice president cars instead of sitting court side. Carol Jefferies confirmed the Perhaps his goal to open the rumors that had spread like wild- track next month is providing fire. She said Superintendent mixed emotions of questions still Michael Johnsen had decided he unanswered coupled with over- would not ask the second-year whelming excitement like that of Mike Westover principal to stay at the helm of a 3 year old on Christmas Eve. the district’s largest school. as “a great man, a great princi- Whatever the reason, In a later interview, Johnsen pal” but said he could not com- when Miller speaks about his himself said it was true. -

THINKING ABOUT STRATEGY by David S. Meyer, UC-Irvine And

THINKING ABOUT STRATEGY by David S. Meyer, UC-Irvine and Suzanne Staggenborg, McGill University Prepared for delivery at American Sociological Association, Collective Behavior/Social Movement Section’s Workshop, “Movement Cultures, Strategies, and Outcomes,” August 9-10, 2007, Hofstra University, Hempstead, New York. On June 24, 2007, a home-made bomb failed to explode near the home of Dr. Arthur Rosenbaum, a research opthamologist at UCLA. The Animal Liberation Brigade claimed credit for the bomb, issuing a communique to an animal rights website. According to the Brigade: 130am on the twenty forth of june: 1 gallon of fuel was placed and set a light under the right front corner of Arthur Rosenbaums large white shiney BMW. He and his wife....are the target of rebellion for the vile and evil things he does to primates at UCLA. We have seen by our own eyes the torture on fully concious primates in his lab. We have heard their whimpers and screeches of pain. Seeing this drove one of us to rush out and vomit. We have seen hell and its in Rosenbaums lab. Rosenbaum, you need to watch your back because next time you are in the operating room or walking to your office you just might be facing injections into your eyes like the primates, you sick twisted fuck” (Animal Liberation Brigade, 2007, sic). The bomb alerted scientists about dangers they might face if they used certain animals in their experiments, and signaled to animal rights sympathizers that aggressive action was possible. It also engaged a range of authorities. The FBI’s counterterrorism division in Los Angeles responded, offering a reward of $110,000 for information leading to the arrests and convictions of those responsible for the attack (Gordon 2007).