Bullish Markets I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nailor Life Safety and Air Control Products

IINSTALLATION, OOPERATION & MMAINTENANCE MM Fire, Smoke, Ceiling AA and Control Dampers An Installation, Operation and NN Maintenance Manual for Nailor Life Safety and Air Control Products. • Curtain Type Fire Dampers UU • Multi-Blade & True Round Fire Dampers • Smoke Dampers • Combination Fire/Smoke Dampers AA • Ceiling Dampers/Fire Rated Diffusers • Accessories • Control and LL Backdraft Dampers IOM Manual Fire, Smoke, Ceiling and Control Dampers Contents Doc. Issue Date Page No. Curtain Type Fire Dampers Model Series: (D)0100, 0200, 0300, (D)0500 Factory Furnished Sleeve Details (Non-Integral Sleeve) FDSTDSL 5/02 1.010-1.011 Integral Sleeve Fire Dampers Details Model Series 01X4-XX Static FDINTSL 2/05 1.020-1.021 Model Series D01X4-XX Dynamic FDINTSLD 1/14 1.022-1.023 Fire Damper Sizing Charts: Model Series (D)0100 & (D)0500 Standard 4 1/4" Frame FDSC 5/02 1.030-1.031 Model Series 0200 & 0500 Thinline 2" Frame FDTSC 5/02 1.040-1.041 Standard Installation Instructions: Standard & Wide Frame, Series (D)0100, 0300, (D)0510-0530 FDINST 1/14 1.050-1.053 Thinline Frame, Models 0210-0240, 0570-0590 FDTINST 8/07 1.060-1.061 Hybrid Type D0100HY Series FDHYINST 9/07 1.062-1.063 Fire Damper Installation Instructions: Model Series (D)0100G, 0200G FDGINST 1/08 1.070-1.071 Out Of Wall Fire Damper Installation Instructions: Model Series (D)0110GOW FDGOWINST 5/15 1.072-1.073 Model Series (D)0110DOW FDDOWINST 6/21 1.074-1.075 Inspection & Maintenance Procedures FDIMP 3/16 1.080-1.081 Accessories: Electro-Thermal Link (ETL) FDETL 5/02 1.090-1.091 Pull-Tab Release For Spring Loaded Dampers (PT) FDPTR 5/02 1.100-1.101 6/19 Contents Page 1 of 4 Nailor Industries Inc. -

Medieval Population Dynamics to 1500

Medieval Population Dynamics to 1500 Part C: the major population changes and demographic trends from 1250 to ca. 1520 European Population, 1000 - 1300 • (1) From the ‘Birth of Europe’ in the 10th century, Europe’s population more than doubled: from about 40 million to at least 80 million – and perhaps to as much as 100 million, by 1300 • (2) Since Europe was then very much underpopulated, such demographic growth was entirely positive: Law of Eventually Diminishing Returns • (3) Era of the ‘Commercial Revolution’, in which all sectors of the economy, led by commerce, expanded -- with significant urbanization and rising real incomes. Demographic Crises, 1300 – 1500 • From some time in the early 14th century, Europe’s population not only ceased to grow, but may have begun its long two-century downswing • Evidence of early 14th century decline • (i) Tuscany (Italy): best documented – 30% -40% population decline before the Black Death • (ii) Normandy (NW France) • (iii) Provence (SE France) • (iv) Essex, in East Anglia (eastern England) The Estimated Populations of Later Medieval and Early Modern Europe Estimates by J. C. Russell (red) and Jan de Vries (blue) Population of Florence (Tuscany) Date Estimated Urban Population 1300 120,000 1349 36,000? 1352 41, 600 1390 60,000 1427 37,144 1459 37,369 1469 40,332 1488 42,000 1526 (plague year) 70,000 Evidence of pre-Plague population decline in 14th century ESSEX Population Trends on Essex Manors The Great Famine: Malthusian Crisis? • (1) The ‘Great Famine’ of 1315-22 • (if we include the sheep -

Two Fourteenth–Century Coin Hoards from Lancashire

Contrebis 2019 v37 TWO FOURTEENTH–CENTURY COIN HOARDS FROM LANCASHIRE Carl Savage Abstract This paper discusses two medieval coin hoards recently discovered near Clitheroe and places them in their historical and numismatic context. The hoards were reported to Stuart Noon, the Finds Liaison Officer (FLO) for Lancashire and Cumbria, who asked the author to identify and interpret them. Discovery and summary of the contents The smaller of the two hoards was discovered in early 2017 in a field close to Pendleton Hall, south-east of Clitheroe. Its Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) reference number is LANCUM- 18B6DA. The hoard contained six silver pennies of Edward I (who reigned between 1272 and 1307). There was no evidence of a container. Analysis of the LiDAR data shows that the hoard was not associated with any archaeological features. The small size of the hoard suggests that this was a purse hoard rather than a savings hoard. The second and larger of the two hoards was discovered in late 2017 by multiple finders in a field between the villages of Sawley and Rimington, near Swanside Beck, north-east of Clitheroe (PAS number LANCUM-730B56). The coins were discovered scattered over an area of 15m² with no evidence of a container. Analysis of the LiDAR data shows that the hoard is not associated with any other nearby archaeological features. The Sawley hoard comprises 37 silver coins of Edward I and Edward II (r. 1307–27) and two silver Scottish pennies of Alexander III (r.1249–86) and John Baliol (r. 1292–6), giving a total of 39 coins in total. -

178 LAST Year, the Second Part of My Address Ended with Both A

178 PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS Great Melton, Norfolk (additional). May 1989. 5 AR denarii to Marcus Aurelius. Waddington, Lanes. October 1989. 30 AR denarii, to Hadrian. Sutton, Suffolk (additional). April 1990. 3 AR denarii, c. 43 AD. Medieval and Modern Springthorpe, Lines. Aug-Sept. 1990. c. 46 AR, pennies and fragments of Edward the Confessor, Helmet type, c. 1055. Torksey, Lines. Spring 1990. 10 AR, William II BMC type III, c. 1073. Wingham, Kent. Throughout 1990. 531 AR pennies, Edward I, mid 1290s. Sutton-on-Sea, Lines. September 1990. 21 AR, halfgroat and pennies, 1380s. Reigate, Surrey. September 1990. 135 AU, c. 6,700 AR, Edward I-Henry VI, c. 1460. Barrow Gurney, Avon. June 1990. 59 AR, c. 1605.] LAST year, the second part of my address ended with both a conclusion and a promise: the conclusion, based on close scrutiny of manuscripts written contemporaneously with the experiments of Eloy Mestrell in mill-struck coinage, was that that coinage was indeed produced, notwithstanding some recently expressed doubts, by a press; and the promise was that I would report back to you as soon as may be on experiments which I had set in train to ascertain, first, what electron microscopy could tell us about the structure of Mestrell's coins and, second, what a series of trial strikings in a screw press, using blanks differing in thickness and in hardness and without the restraining effect of a collar, could tell us about observed characteristics of Mestrell's coins, such as fish-tailing. I am happy to say that these experiments are now complete and it is my pleasant duty readily to acknowledge my debt to David Sellwood for his helpful advice in general; to my colleague in the University of Leeds, Dr Christopher Hammond of the School of Materials, Dr Peter Hatherley, Manager Materials Development at the Royal Mint, Neil Philips and Gillian Prosser of the same institution who between them conducted the microscopy work; and to Mr Haydn Walters and his colleagues in the Royal Mint who undertook the trial strikings. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Barbara J. Newman Professor of English; affiliated with Classics, History, and Religious Studies John Evans Professor of Latin Language and Literature Department of English Phone: 847-491-5679 University Hall 215 Fax: 847-467-1545 Northwestern University Email: [email protected] Evanston, IL 60208-2240 Education Ph.D. 1981, Yale University, Department of Medieval Studies M.A.Div. 1976, University of Chicago Divinity School B.A. 1975, Oberlin College, summa cum laude in English and Religion Employment John Evans Professor of Latin, Northwestern University, 2003-; Professor of English and Religion, 1992- ; Associate Professor, 1987-92; Assistant Professor, 1981-87. Books The Permeable Self: Five Medieval Relationships. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, forthcoming fall 2021. The Works of Richard Methley. Translation, with introduction by Laura Saetveit Miles. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press / Cistercian Publications, Jan. 2021. Paper and digital. Mechthild of Hackeborn and the Nuns of Helfta, The Book of Special Grace. Translation with introduction. New York: Paulist Press (Classics of Western Spirituality), 2017. Cloth and digital. Making Love in the Twelfth Century: Letters of Two Lovers in Context. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016. Cloth and digital; paperback, 2020. Medieval Crossover: Reading the Secular against the Sacred. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2013. Paper. The Life of Juliana of Cornillon: introduction, chronology, translation, and notes. In Living Saints of the Thirteenth Century: The Lives of Yvette, Anchoress of Huy; Juliana of Cornillon, Author of the Corpus Christi Feast; and Margaret the Lame, Anchoress of Magdeburg, ed. Anneke B. Mulder-Bakker, 143-302. Turnhout: Brepols, 2011. Cloth. 2 Thomas of Cantimpré, The Collected Saints’ Lives: Abbot John of Cantimpré, Christina the Astonishing, Margaret of Ypres, and Lutgard of Aywières, ed. -

Day of Pentecost May 31St, 2020

Day of Pentecost May 31st, 2020 Pentecost The term means "the fiftieth day." It is used in both the OT and the NT. In the OT it refers to a feast of seven weeks known as the Feast of Weeks. It was apparently an agricultural event that focused on the harvesting of first fruits. Josephus referred to Pentecost as the fiftieth day after the first day of Passover. The term is used in the NT to refer to the coming of the Spirit on the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:1), shortly after Jesus' death, resurrection, and ascension. Christians came to understand the meaning of Pentecost in terms of the gift of the Spirit. The Pentecost event was the fulfillment of a promise which Jesus gave concerning the return of the Holy Spirit. The speaking in tongues, which was a major effect of having received the Spirit, is interpreted by some to symbolize the church's worldwide preaching. In the Christian tradition, Pentecost is now the seventh Sunday after Easter. It emphasizes that the church is understood as the body of Christ which is drawn together and given life by the Holy Spirit. Some understand Pentecost to be the origin and sending out of the church into the world. The Day of Pentecost is one of the seven principal feasts of the church year in the Episcopal Church (BCP, p. 15). 2 The Day of Pentecost is identified by the BCP as one of the feasts that is "especially appropriate" for baptism (p. 312). The liturgical color for the feast is red. -

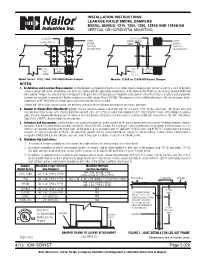

Installation Instructions, Model Series

INSTALLATION INSTRUCTIONS LEAKAGE RATED SMOKE DAMPERS MODEL SERIES: 1210, 1260, 1280, 1290S AND 1290S-SS VERTICAL OR HORIZONTAL MOUNTING SLEEVE/DUCT #8 FASTENER SMOKE DAMPER FRAME/ SMOKE SEALANT (NOTE 3) BARRIER SLEEVE BARRIER (VERTICAL (VERTICAL OR HORIZONTAL) OR HORIZONTAL) FIRST 24" (610) FIRST 24" (610) DUCT MAX. DUCT MAX. OUTLET OUTLET Model Series: 1210, 1260, 1280 Multi-Blade Damper Models: 1290S or 1290S-SS Round Damper NOTES: 1. Installation and Location Requirements: Smoke dampers are required where building codes require a leakage rated damper as part of a static or dynamic smoke management system. Installation shall be in accordance with the appropriate requirements of the National Fire Protection Association Bulletin NFPA 90A latest edition. Dampers are to be installed at or adjacent to the point where the duct passes through the smoke barrier unless the damper is used to isolate equipment. Dampers are designed to operate with blades running horizontally (except Model 1210VB). The damper must be installed with plane of the closed damper blades a maximum of 24" (610) from the smoke barrier and before any duct inlets or outlet. Damper must be installed square, plumb, and free from racking to ensure optimum performance and correct operation. 2. Damper to Sleeve/Duct Attachment: Damper shall be secured to sleeve or duct with 1/4" (6) long welds, 3/16" (5) dia. steel rivets, 1/4" (6) dia. bolts and nuts, #8 sheet metal screws, 3/16" (5) dia. buttonloks on both sides, at 6" (152) on center and a maximum of 4" (102) from the corners of the damper on all four sides. -

Covenants and the Law of Proof, 1290–1321 John Baker It Is

DEEDS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS: COVENANTS AND THE LAW OF PROOF, 1290–1321 John Baker It is somewhat rash to venture an opinion on late-thirteenth-century law in the presence of one who knows everything there is to know about the law of that period, but since this seems to be the one topic on which Pro- fessor Brand has not yet pronounced perhaps these musings will provoke a definitive response from him. The question is, when and why did the central courts of Common Law come to insist on specialty, a sealed writ- ing, to prove a covenant. The contradictory literature is profoundly per- plexing to those of us who have found ourselves lecturing on the history of the law of contract; but our starting point is on fairly clear ground. There are four basic assertions which can be made with reasonable confidence. First, contrary to what was once sometimes thought,1 it was not an immemorial rule that a deed was required. There is no clear indication in the records of a rule requiring a deed before the 1290s,2 and we still find covenant cases being tried by jury or wager of law in that decade; but there are signs in the year books of an emerging rule in the 1290s and 1300s, and an invariable rule after 1321. Secondly, the rule applied at first in some actions of covenant and not in others; and it could sometimes apply to covenants pleaded in other forms of action. It was not therefore, in origin, a rule about a specific form of action, but about the underlying elements of the action. -

February 15, 2021 Dear Participants in The

Thomas J. McSweeney Robert and Elizabeth Scott Research Professor of Law P.O. Box 8795 Williamsburg, VA 23187-8795 Phone: 757-221-3829 Fax: 757-221-3261 Email: [email protected] February 15, 2021 Dear Participants in the Columbia Legal History Workshop: I am delighted to have the opportunity to present Writing the Common Law in Latin in the Later Thirteenth Century to you. I wanted to give you some context for this project. I’m interested in treatise-writing as a practice. Why do people choose to write treatises? I published my first book, Priests of the Law, a little over a year ago. Priests of the Law is about Bracton, a major treatise of the early to mid-thirteenth century. I have now moved on to a project on the later thirteenth century. A number of (mostly shorter) tracts on the common law survive from the period between about 1260 and 1300. These texts are some of the earliest evidence we have for the education of the lawyers who practiced in the English royal courts. Some even appear to be derived from lecture courses on the common law that we otherwise known nothing about. And yet many of them have never been edited. I have begun to edit and translate some of these texts. As I have been working my way through them, I have been looking for connections and trying to make sense of some of the oddities I have been finding in these texts. This paper is my attempt to make sense of the differences in language I have found. -

The Economy of Byzantine Macedonia in the Palaiologan Period

Angeliki E. Laiou The economy of ByzantineMacedonia in the Palaiologanperiod For much of the Palaiologan period, Macedonia was the most important part of the Palaiologan state in economic terms, and thus its investigation is well worth undertaking. As we shall see, until the 1340s it was fairly well articulated, and therefore may also be studied as a model of a late medieval economy. In what follows, I shall examine the articulation of the economy of Macedonia, and also the stresses and strains on the system. The topic cannot be discussed with the same assumptions for the entire Palaiologan period. A sharp dividing line must be drawn in the middle of the fourteenth century; and it has been argued that there is yet another dividing line in the 1420s, although I believe that in the latter case the indicators are far from clear. 1 A number of conditions important for the economy, that later would disappear or undergo fundamental changes, obtained until the 1340s. There was still a state which considered it its duty to provide minimal security for its subjects, even though it was a duty it frequently could not perform. For the countryside that meant some concern for security so that agricultural activities could be pursued. Although security was adversely affected by Serbian incursions in the 1280s and 1290s, the Catalan invasions of 1307-9 and the first civil war of the 1320s, at least the intent of safeguarding it was still there, as was the effort of the emperors to protect Byzantine merchants from the provinces, including the city of Thessaloniki, against piratical or semi-piratical attacks from the merchants and seamen of the Italian city states. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Middle English romance, attitudes to kingship and political crisis, c.l272-c.l350 Lucas, Karen How to cite: Lucas, Karen (1997) Middle English romance, attitudes to kingship and political crisis, c.l272-c.l350, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4637/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Middle English romance, attitudes to kingship and political crisis, C.1272-C.1350 by Karen Lucas M. A. (Durham) The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the written consent of the author and information derived from it should be acknowledged. This thesis is presented in candidature for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Durham 1997 1 I AUG watt Abstract. Middle English romance, attitudes to kingship and political crisis, C.1272-C.1350 Karen Lucas Ph.D. -

JCC: War of the Bucket, Italy 1325: Bologna Background Guide Table of Contents

JCC: War Of The Bucket, Italy 1325: Bologna Background Guide Table of Contents Letter from the Chair Letter from the Crisis Director Committee Logistics Introduction to the Committee Introduction to Topic One History of the Problem Past Actions Taken Current Events Questions to Consider Resources to Use Introduction to Topic Two History of the Problem Past Actions Taken Current Events Questions to Consider Resources to Use Bibliography Staff of the Committee Chair Mariah Mansoor Vice Chair So Min Cho Crisis Director Elisa Cifiello Assistant Crisis Director Mary Thomas Under Secretary General Jane Gallagher Taylor Cowser, Secretary General Neha Iyer, Director General Letter from the Chair Hello Delegates! Welcome to JCC: War of the Bucket: Bologna! My name is Mariah Mansoor and I will be the chair for this committee . I am working alongside the vice chair So Min Cho, your crisis director, Elisa Cifiello, and assistant crisis director, Mary Thomas. We are all working together to ensure you have an amazing and fulfilling experience in February . I am a sophomore at Boston University studying Mechanical Engineering with a concentration in Energy Technologies. I love visiting museums and reading sci-fi and fantasy novels when I get the chance. My biggest addiction is Netflix and watching any new tv show or movie. Right now, I love mystery movies specifically murder mystery. I am originally from Boston, I grew up in Allston-Brighton and I attended high school in the city. I highly recommend exploring the city during conference weekend. I participated in MUN throughout High School and I chaired a general committee for BosMUN last year.