Two Fourteenth–Century Coin Hoards from Lancashire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes of a Meeting of the Industrial Commission of North Dakota Held on October 22, 2019 Beginning at 12:30 P.M

Minutes of a Meeting of the Industrial Commission of North Dakota Held on October 22, 2019 beginning at 12:30 p.m. Governor’s Conference Room - State Capitol Present: Governor Doug Burgum, Chairman Attorney General Wayne Stenehjem Agriculture Commissioner Doug Goehring Also Present: Other attendees are listed on the attendance sheet available in the Commission files Members of the Press Governor Burgum called the Industrial Commission meeting to order at approximately 12:30 p.m. and the Commission took up Oil & Gas Research Program (OGRP) business. OIL & GAS RESEARCH PROGRAM Ms. Karlene Fine, Industrial Commission Executive Director, provided the Oil and Gas Research Fund financial report for the period ending August 31, 2019. She stated that there is $8.8 million of uncommitted funding available for project awards during the 2019-2021 biennium. Ms. Fine presented the Oil and Gas Research Council 2019-2021 budget recommendation and stated the budget includes the uncommitted dollars and the payments scheduled for projects previously approved by the Commission. It was moved by Commissioner Goehring and seconded by Attorney General Stenehjem that the Industrial Commission accepts the Oil and Gas Research Council’s recommendation and approves the following 2019-2021 biennium allocation for Oil and Gas Research Program funding: Research 46.70% $ 7,770,415 Education 8.42% $ 1,350,000 Pipeline Authority 4.37% $ 700,000 Administration 1.20% $ 300,000 Legislative Directive 39.31% $ 6,300,000 $16,420,415 and further authorizes the Industrial Commission Executive Director/Secretary to transfer $700,000 from the Oil and Gas Research Fund to the Pipeline Authority Fund during the 2019-2021 biennium. -

Nailor Life Safety and Air Control Products

IINSTALLATION, OOPERATION & MMAINTENANCE MM Fire, Smoke, Ceiling AA and Control Dampers An Installation, Operation and NN Maintenance Manual for Nailor Life Safety and Air Control Products. • Curtain Type Fire Dampers UU • Multi-Blade & True Round Fire Dampers • Smoke Dampers • Combination Fire/Smoke Dampers AA • Ceiling Dampers/Fire Rated Diffusers • Accessories • Control and LL Backdraft Dampers IOM Manual Fire, Smoke, Ceiling and Control Dampers Contents Doc. Issue Date Page No. Curtain Type Fire Dampers Model Series: (D)0100, 0200, 0300, (D)0500 Factory Furnished Sleeve Details (Non-Integral Sleeve) FDSTDSL 5/02 1.010-1.011 Integral Sleeve Fire Dampers Details Model Series 01X4-XX Static FDINTSL 2/05 1.020-1.021 Model Series D01X4-XX Dynamic FDINTSLD 1/14 1.022-1.023 Fire Damper Sizing Charts: Model Series (D)0100 & (D)0500 Standard 4 1/4" Frame FDSC 5/02 1.030-1.031 Model Series 0200 & 0500 Thinline 2" Frame FDTSC 5/02 1.040-1.041 Standard Installation Instructions: Standard & Wide Frame, Series (D)0100, 0300, (D)0510-0530 FDINST 1/14 1.050-1.053 Thinline Frame, Models 0210-0240, 0570-0590 FDTINST 8/07 1.060-1.061 Hybrid Type D0100HY Series FDHYINST 9/07 1.062-1.063 Fire Damper Installation Instructions: Model Series (D)0100G, 0200G FDGINST 1/08 1.070-1.071 Out Of Wall Fire Damper Installation Instructions: Model Series (D)0110GOW FDGOWINST 5/15 1.072-1.073 Model Series (D)0110DOW FDDOWINST 6/21 1.074-1.075 Inspection & Maintenance Procedures FDIMP 3/16 1.080-1.081 Accessories: Electro-Thermal Link (ETL) FDETL 5/02 1.090-1.091 Pull-Tab Release For Spring Loaded Dampers (PT) FDPTR 5/02 1.100-1.101 6/19 Contents Page 1 of 4 Nailor Industries Inc. -

LOGIQ 500 Service Manual

ULTRASOUND PROGRAM MANAGEMENT GROUP UPDATE INSTRUCTIONS Date : August 28, 2000 To : Holders of P9030TA LOGIQ 500 Service Manual Subject : P9030TA LOGIQ 500 SERVICE MANUAL UPGRADE – REV 14 Enclosed please find the following Rev14 upgrade pages. SUMMARY OF CHANGES (Reason) • Chapter 1: Addition of the caution label and change of address • Chapter 3: Additional information for Ver. 6 system and the new probes • Chapter 4: Additional information for Ver. 6 system software options • Chapter 5: Additional information for Ver. 6 system • Chapter 6: Additional descriptions for new FRUs and others UPDATE INSTRUCTIONS To properly upgrade your manual, exchange the upgraded pages in the list below: REMOVE PAGE SHEETS INSERT PAGE SHEETS CHAPTER NUMBERS (Pgs) NUMBERS (Pgs) Title page REV 13 1 Title page REV 14 1 A REV 13 1 A REV 14 1 i to vi 3 i to vi 3 1 1–1 to 1–2 1 1–1 to 1–2 1 1–9 to 1–20 6 1–9 to 1–22 7 3 3–1 to 3–2 1 3–1 to 3–2 1 3–11 to 3–16 3 3–11 to 3–18 4 4 4–1 to 4–2 1 4–1 to 4–2 1 4–15 to 4–16 1 4–15 to 4–16 1 4–21 to 4–26 3 4–21 to 4–26 3 4–35 to 4–40 3 4–35 to 4–42 4 5 5–11 to 5–12 1 5–11 to 5–12 1 6 6–1 to 6–252 126 6–1 to 6–266 133 TOTAL TOTAL REMOVED 151 INSERTED 161 Yuji Kato US PROGRAM MANAGEMENT GROUP – ULTRASOUND BUSINESS DIVISION, GEYMS P9030TA Revision 14 LOGIQ 500 Service Manual Copyright 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000 by General Electric Company GE MEDICAL SYSTEMS LOGIQ 500 SERVICE MANUAL REV 14 P9030TA LIST OF EFFECTIVE PAGES REV DATE PRIMARY REASON FOR CHANGE 0 March 10, 1994 Initial release 1 July 25, 1994 Software -

The Pious and Political Networks of Catherine of Siena

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College 5-23-2018 The Pious and Political Networks of Catherine of Siena Aubrie Kent Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Kent, Aubrie, "The Pious and Political Networks of Catherine of Siena" (2018). University Honors Theses. Paper 553. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.559 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Abstract This project looks at the career of St. Catherine of Siena and argues that without the relationships she had with her closest followers, who provided social connections and knowledge of the operation of political power, she would not have been able to pursue as active or wide-ranging a career. The examination of Catherine’s relationships, the careers of her followers, and the ways she made use of this network of support, relies mainly on Catherine’s extant letters. Most prior research on St. Catherine focuses on her spirituality and work with the papacy, which leaves out the influence of her local, political environment and the activities of her associates. This work examines Catherine’s place on Siena’s political landscape and within the system of Italian politics more generally. THE PIOUS AND POLITICAL NETWORKS OF CATHERINE OF SIENA by AUBRIE KENT A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS in HISTORY Portland State University 2018 Table of Contents Chronology i Introduction 1 Religious Background 7 Political Background 22 Magnate Families 32 Spiritual Family 50 Conclusion 68 Catherine’s Associates 76 Bibliography 79 Chronology 1347 Catherine is born. -

Medieval Population Dynamics to 1500

Medieval Population Dynamics to 1500 Part C: the major population changes and demographic trends from 1250 to ca. 1520 European Population, 1000 - 1300 • (1) From the ‘Birth of Europe’ in the 10th century, Europe’s population more than doubled: from about 40 million to at least 80 million – and perhaps to as much as 100 million, by 1300 • (2) Since Europe was then very much underpopulated, such demographic growth was entirely positive: Law of Eventually Diminishing Returns • (3) Era of the ‘Commercial Revolution’, in which all sectors of the economy, led by commerce, expanded -- with significant urbanization and rising real incomes. Demographic Crises, 1300 – 1500 • From some time in the early 14th century, Europe’s population not only ceased to grow, but may have begun its long two-century downswing • Evidence of early 14th century decline • (i) Tuscany (Italy): best documented – 30% -40% population decline before the Black Death • (ii) Normandy (NW France) • (iii) Provence (SE France) • (iv) Essex, in East Anglia (eastern England) The Estimated Populations of Later Medieval and Early Modern Europe Estimates by J. C. Russell (red) and Jan de Vries (blue) Population of Florence (Tuscany) Date Estimated Urban Population 1300 120,000 1349 36,000? 1352 41, 600 1390 60,000 1427 37,144 1459 37,369 1469 40,332 1488 42,000 1526 (plague year) 70,000 Evidence of pre-Plague population decline in 14th century ESSEX Population Trends on Essex Manors The Great Famine: Malthusian Crisis? • (1) The ‘Great Famine’ of 1315-22 • (if we include the sheep -

Taking Notae on King and Cleric: Thibaut, Adam, and the Medieval Readers of the Chansonnier De Noailles (T-Trouv.)

_full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien B2 voor dit chapter en nul 0 in hierna): 0 _full_alt_articletitle_running_head (oude _articletitle_deel, vul hierna in): Taking Notae on King and Cleric _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 Taking Notae On King And Cleric 121 Chapter 5 Taking Notae on King and Cleric: Thibaut, Adam, and the Medieval Readers of the Chansonnier de Noailles (T-trouv.) Judith A. Peraino The serpentine flourishes of the monogram Nota in light brown ink barely catch the eye in the marginal space beside a wide swath of much darker and more compact letters (see Figure 5.1). But catch the eye they do, if not in the first instance, then at some point over the course of their fifty-five occurrences throughout the 233 folios of ms. T-trouv., also known as the Chansonnier de Noailles.1 In most cases the monogram looks more like Noā – where the “a” and the “t” have fused into one peculiar ligature. Variations of the monogram indi- cate a range of more or less swift and continuous execution (see Figure 5.2), but consistency in size and ink color strongly suggest the work of a single an- notator. Adriano Cappelli’s Dizionario di abbreviature latine ed italiane includes a nearly exact replica of this scribal shorthand for nota, which he dates to the thirteenth century.2 Thus the notae, and the act of reading they indicate, took place soon after its compilation in the 1270s or 1280s. Ms. T-trouv. conveys the sense of a carefully compiled, ordered, and execut- ed compendium of writings, some designed with music in mind, others not. -

Gila Cliff Dwellings

GILA CLIFF DWELLINGS YOUR VISIT ACCOMMODATIONS AND SERVICE. Improved campgrounds and picnic areas are available. For information on their location and use, Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument is a 44-mile drive north inquire at the visitor center or ask a uniformed ranger. Although there from Silver City on State Highway 15. The approximate driving time are no accommodations within the monument, the nearby town of Gila is 2 hours. There is no public transportation to the monument, Hot Springs has overnight lodging and a grocery store that sells camp which is open all year except December 25 and January 1. ing supplies and gasoline. Arrangements for horse rentals and guided pack trips may be made in town also. Your first stop should be the visitor center (jointly operated by the National Park Service and the U.S. Forest Service) where you may WHAT IS EXPECTED OF YOU. Removing or marring any natural obtain information and suggestions that will add to the enjoyment of or man-made object is not allowed. Hunting is not permitted within your visit. The visitor center is open from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. through the monument. Pets are not allowed within the monument; kennels out the year. are available. The speed limit within the area is 25 miles an hour. Drive carefully and enjoy the scenery. Trash containers are not available; Visiting hours at the ruins vary seasonally; call 505-536-9461 for cur please pack out your trash and leave the places you visit clean for rent information on hours of operation. -

178 LAST Year, the Second Part of My Address Ended with Both A

178 PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS Great Melton, Norfolk (additional). May 1989. 5 AR denarii to Marcus Aurelius. Waddington, Lanes. October 1989. 30 AR denarii, to Hadrian. Sutton, Suffolk (additional). April 1990. 3 AR denarii, c. 43 AD. Medieval and Modern Springthorpe, Lines. Aug-Sept. 1990. c. 46 AR, pennies and fragments of Edward the Confessor, Helmet type, c. 1055. Torksey, Lines. Spring 1990. 10 AR, William II BMC type III, c. 1073. Wingham, Kent. Throughout 1990. 531 AR pennies, Edward I, mid 1290s. Sutton-on-Sea, Lines. September 1990. 21 AR, halfgroat and pennies, 1380s. Reigate, Surrey. September 1990. 135 AU, c. 6,700 AR, Edward I-Henry VI, c. 1460. Barrow Gurney, Avon. June 1990. 59 AR, c. 1605.] LAST year, the second part of my address ended with both a conclusion and a promise: the conclusion, based on close scrutiny of manuscripts written contemporaneously with the experiments of Eloy Mestrell in mill-struck coinage, was that that coinage was indeed produced, notwithstanding some recently expressed doubts, by a press; and the promise was that I would report back to you as soon as may be on experiments which I had set in train to ascertain, first, what electron microscopy could tell us about the structure of Mestrell's coins and, second, what a series of trial strikings in a screw press, using blanks differing in thickness and in hardness and without the restraining effect of a collar, could tell us about observed characteristics of Mestrell's coins, such as fish-tailing. I am happy to say that these experiments are now complete and it is my pleasant duty readily to acknowledge my debt to David Sellwood for his helpful advice in general; to my colleague in the University of Leeds, Dr Christopher Hammond of the School of Materials, Dr Peter Hatherley, Manager Materials Development at the Royal Mint, Neil Philips and Gillian Prosser of the same institution who between them conducted the microscopy work; and to Mr Haydn Walters and his colleagues in the Royal Mint who undertook the trial strikings. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Barbara J. Newman Professor of English; affiliated with Classics, History, and Religious Studies John Evans Professor of Latin Language and Literature Department of English Phone: 847-491-5679 University Hall 215 Fax: 847-467-1545 Northwestern University Email: [email protected] Evanston, IL 60208-2240 Education Ph.D. 1981, Yale University, Department of Medieval Studies M.A.Div. 1976, University of Chicago Divinity School B.A. 1975, Oberlin College, summa cum laude in English and Religion Employment John Evans Professor of Latin, Northwestern University, 2003-; Professor of English and Religion, 1992- ; Associate Professor, 1987-92; Assistant Professor, 1981-87. Books The Permeable Self: Five Medieval Relationships. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, forthcoming fall 2021. The Works of Richard Methley. Translation, with introduction by Laura Saetveit Miles. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press / Cistercian Publications, Jan. 2021. Paper and digital. Mechthild of Hackeborn and the Nuns of Helfta, The Book of Special Grace. Translation with introduction. New York: Paulist Press (Classics of Western Spirituality), 2017. Cloth and digital. Making Love in the Twelfth Century: Letters of Two Lovers in Context. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016. Cloth and digital; paperback, 2020. Medieval Crossover: Reading the Secular against the Sacred. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2013. Paper. The Life of Juliana of Cornillon: introduction, chronology, translation, and notes. In Living Saints of the Thirteenth Century: The Lives of Yvette, Anchoress of Huy; Juliana of Cornillon, Author of the Corpus Christi Feast; and Margaret the Lame, Anchoress of Magdeburg, ed. Anneke B. Mulder-Bakker, 143-302. Turnhout: Brepols, 2011. Cloth. 2 Thomas of Cantimpré, The Collected Saints’ Lives: Abbot John of Cantimpré, Christina the Astonishing, Margaret of Ypres, and Lutgard of Aywières, ed. -

Day of Pentecost May 31St, 2020

Day of Pentecost May 31st, 2020 Pentecost The term means "the fiftieth day." It is used in both the OT and the NT. In the OT it refers to a feast of seven weeks known as the Feast of Weeks. It was apparently an agricultural event that focused on the harvesting of first fruits. Josephus referred to Pentecost as the fiftieth day after the first day of Passover. The term is used in the NT to refer to the coming of the Spirit on the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:1), shortly after Jesus' death, resurrection, and ascension. Christians came to understand the meaning of Pentecost in terms of the gift of the Spirit. The Pentecost event was the fulfillment of a promise which Jesus gave concerning the return of the Holy Spirit. The speaking in tongues, which was a major effect of having received the Spirit, is interpreted by some to symbolize the church's worldwide preaching. In the Christian tradition, Pentecost is now the seventh Sunday after Easter. It emphasizes that the church is understood as the body of Christ which is drawn together and given life by the Holy Spirit. Some understand Pentecost to be the origin and sending out of the church into the world. The Day of Pentecost is one of the seven principal feasts of the church year in the Episcopal Church (BCP, p. 15). 2 The Day of Pentecost is identified by the BCP as one of the feasts that is "especially appropriate" for baptism (p. 312). The liturgical color for the feast is red. -

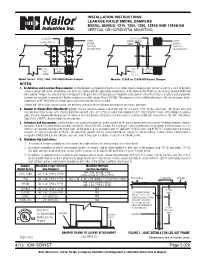

Installation Instructions, Model Series

INSTALLATION INSTRUCTIONS LEAKAGE RATED SMOKE DAMPERS MODEL SERIES: 1210, 1260, 1280, 1290S AND 1290S-SS VERTICAL OR HORIZONTAL MOUNTING SLEEVE/DUCT #8 FASTENER SMOKE DAMPER FRAME/ SMOKE SEALANT (NOTE 3) BARRIER SLEEVE BARRIER (VERTICAL (VERTICAL OR HORIZONTAL) OR HORIZONTAL) FIRST 24" (610) FIRST 24" (610) DUCT MAX. DUCT MAX. OUTLET OUTLET Model Series: 1210, 1260, 1280 Multi-Blade Damper Models: 1290S or 1290S-SS Round Damper NOTES: 1. Installation and Location Requirements: Smoke dampers are required where building codes require a leakage rated damper as part of a static or dynamic smoke management system. Installation shall be in accordance with the appropriate requirements of the National Fire Protection Association Bulletin NFPA 90A latest edition. Dampers are to be installed at or adjacent to the point where the duct passes through the smoke barrier unless the damper is used to isolate equipment. Dampers are designed to operate with blades running horizontally (except Model 1210VB). The damper must be installed with plane of the closed damper blades a maximum of 24" (610) from the smoke barrier and before any duct inlets or outlet. Damper must be installed square, plumb, and free from racking to ensure optimum performance and correct operation. 2. Damper to Sleeve/Duct Attachment: Damper shall be secured to sleeve or duct with 1/4" (6) long welds, 3/16" (5) dia. steel rivets, 1/4" (6) dia. bolts and nuts, #8 sheet metal screws, 3/16" (5) dia. buttonloks on both sides, at 6" (152) on center and a maximum of 4" (102) from the corners of the damper on all four sides. -

Covenants and the Law of Proof, 1290–1321 John Baker It Is

DEEDS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS: COVENANTS AND THE LAW OF PROOF, 1290–1321 John Baker It is somewhat rash to venture an opinion on late-thirteenth-century law in the presence of one who knows everything there is to know about the law of that period, but since this seems to be the one topic on which Pro- fessor Brand has not yet pronounced perhaps these musings will provoke a definitive response from him. The question is, when and why did the central courts of Common Law come to insist on specialty, a sealed writ- ing, to prove a covenant. The contradictory literature is profoundly per- plexing to those of us who have found ourselves lecturing on the history of the law of contract; but our starting point is on fairly clear ground. There are four basic assertions which can be made with reasonable confidence. First, contrary to what was once sometimes thought,1 it was not an immemorial rule that a deed was required. There is no clear indication in the records of a rule requiring a deed before the 1290s,2 and we still find covenant cases being tried by jury or wager of law in that decade; but there are signs in the year books of an emerging rule in the 1290s and 1300s, and an invariable rule after 1321. Secondly, the rule applied at first in some actions of covenant and not in others; and it could sometimes apply to covenants pleaded in other forms of action. It was not therefore, in origin, a rule about a specific form of action, but about the underlying elements of the action.