The Quaternary: Its Character and Definition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climatic Events During the Late Pleistocene and Holocene in the Upper Parana River: Correlation with NE Argentina and South-Central Brazil Joseh C

Quaternary International 72 (2000) 73}85 Climatic events during the Late Pleistocene and Holocene in the Upper Parana River: Correlation with NE Argentina and South-Central Brazil JoseH C. Stevaux* Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul - Instituto de GeocieL ncias - CECO, Universidade Estadual de Maringa& - Geography Department, 87020-900 Maringa& ,PR} Brazil Abstract Most Quaternary studies in Brazil are restricted to the Atlantic Coast and are mainly based on coastal morphology and sea level changes, whereas research on inland areas is largely unexplored. The study area lies along the ParanaH River, state of ParanaH , Brazil, at 223 43S latitude and 533 10W longitude, where the river is as yet undammed. Paleoclimatological data were obtained from 10 vibro cores and 15 motor auger holes. Sedimentological and pollen analyses plus TL and C dating were used to establish the following evolutionary history of Late Pleistocene and Holocene climates: First drier episode ?40,000}8000 BP First wetter episode 8000}3500 BP Second drier episode 3500}1500 BP Second (present) wet episode 1500 BP}Present Climatic intervals are in agreement with prior studies made in southern Brazil and in northeastern Argentina. ( 2000 Elsevier Science Ltd and INQUA. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction the excavation of Sete Quedas Falls on the ParanaH River (today the site of the Itaipu dam). Barthelness (1960, Geomorphological and paleoclimatological studies of 1961) de"ned a regional surface in the Guaira area de- the Upper ParanaH River Basin are scarce and regional in veloped at the end of the Pleistocene (Guaira Surface) nature. King (1956, pp. 157}159) de"ned "ve geomor- and correlated it with the Velhas Cycle. -

Geological-Geomorphological and Paleontological Heritage in the Algarve (Portugal) Applied to Geotourism and Geoeducation

land Article Geological-Geomorphological and Paleontological Heritage in the Algarve (Portugal) Applied to Geotourism and Geoeducation Antonio Martínez-Graña 1,* , Paulo Legoinha 2 , José Luis Goy 1, José Angel González-Delgado 1, Ildefonso Armenteros 1, Cristino Dabrio 3 and Caridad Zazo 4 1 Department of Geology, Faculty of Sciences, University of Salamanca, 37008 Salamanca, Spain; [email protected] (J.L.G.); [email protected] (J.A.G.-D.); [email protected] (I.A.) 2 GeoBioTec, Department of Earth Sciences, NOVA School of Science and Technology, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa, Caparica, 2829-516 Almada, Portugal; [email protected] 3 Department of Stratigraphy, Faculty of Geology, Complutense University of Madrid, 28040 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] 4 Department of Geology, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, 28006 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-923294496 Abstract: A 3D virtual geological route on Digital Earth of the geological-geomorphological and paleontological heritage in the Algarve (Portugal) is presented, assessing the geological heritage of nine representative geosites. Eighteen quantitative parameters are used, weighing the scientific, didactic and cultural tourist interest of each site. A virtual route has been created in Google Earth, with overlaid georeferenced cartographies, as a field guide for students to participate and improve their learning. This free application allows loading thematic georeferenced information that has Citation: Martínez-Graña, A.; previously been evaluated by means of a series of parameters for identifying the importance and Legoinha, P.; Goy, J.L.; interest of a geosite (scientific, educational and/or tourist). The virtual route allows travelling from González-Delgado, J.A.; Armenteros, one geosite to another, interacting in real time from portable devices (e.g., smartphone and tablets), I.; Dabrio, C.; Zazo, C. -

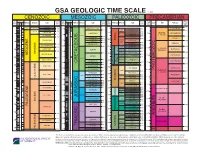

The Geologic Time Scale Is the Eon

Exploring Geologic Time Poster Illustrated Teacher's Guide #35-1145 Paper #35-1146 Laminated Background Geologic Time Scale Basics The history of the Earth covers a vast expanse of time, so scientists divide it into smaller sections that are associ- ated with particular events that have occurred in the past.The approximate time range of each time span is shown on the poster.The largest time span of the geologic time scale is the eon. It is an indefinitely long period of time that contains at least two eras. Geologic time is divided into two eons.The more ancient eon is called the Precambrian, and the more recent is the Phanerozoic. Each eon is subdivided into smaller spans called eras.The Precambrian eon is divided from most ancient into the Hadean era, Archean era, and Proterozoic era. See Figure 1. Precambrian Eon Proterozoic Era 2500 - 550 million years ago Archaean Era 3800 - 2500 million years ago Hadean Era 4600 - 3800 million years ago Figure 1. Eras of the Precambrian Eon Single-celled and simple multicelled organisms first developed during the Precambrian eon. There are many fos- sils from this time because the sea-dwelling creatures were trapped in sediments and preserved. The Phanerozoic eon is subdivided into three eras – the Paleozoic era, Mesozoic era, and Cenozoic era. An era is often divided into several smaller time spans called periods. For example, the Paleozoic era is divided into the Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous,and Permian periods. Paleozoic Era Permian Period 300 - 250 million years ago Carboniferous Period 350 - 300 million years ago Devonian Period 400 - 350 million years ago Silurian Period 450 - 400 million years ago Ordovician Period 500 - 450 million years ago Cambrian Period 550 - 500 million years ago Figure 2. -

Paleoecology and Land-Use of Quaternary Megafauna from Saltville, Virginia Emily Simpson East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2019 Paleoecology and Land-Use of Quaternary Megafauna from Saltville, Virginia Emily Simpson East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Paleontology Commons Recommended Citation Simpson, Emily, "Paleoecology and Land-Use of Quaternary Megafauna from Saltville, Virginia" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3590. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3590 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Paleoecology and Land-Use of Quaternary Megafauna from Saltville, Virginia ________________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Geosciences East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Geosciences with a concentration in Paleontology _______________________________ by Emily Michelle Bruff Simpson May 2019 ________________________________ Dr. Chris Widga, Chair Dr. Blaine W. Schubert Dr. Andrew Joyner Key Words: Paleoecology, land-use, grassy balds, stable isotope ecology, Whitetop Mountain ABSTRACT Paleoecology and Land-Use of Quaternary Megafauna from Saltville, Virginia by Emily Michelle Bruff Simpson Land-use, feeding habits, and response to seasonality by Quaternary megaherbivores in Saltville, Virginia, is poorly understood. Stable isotope analyses of serially sampled Bootherium and Equus enamel from Saltville were used to explore seasonally calibrated (δ18O) patterns in megaherbivore diet (δ13C) and land-use (87Sr/86Sr). -

Variable Impact of Late-Quaternary Megafaunal Extinction in Causing

Variable impact of late-Quaternary megafaunal SPECIAL FEATURE extinction in causing ecological state shifts in North and South America Anthony D. Barnoskya,b,c,1, Emily L. Lindseya,b, Natalia A. Villavicencioa,b, Enrique Bostelmannd,2, Elizabeth A. Hadlye, James Wanketf, and Charles R. Marshalla,b aDepartment of Integrative Biology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720; bMuseum of Paleontology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720; cMuseum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720; dRed Paleontológica U-Chile, Laboratoria de Ontogenia, Departamento de Biología, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Chile, Chile; eDepartment of Biology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305; and fDepartment of Geography, California State University, Sacramento, CA 95819 Edited by John W. Terborgh, Duke University, Durham, NC, and approved August 5, 2015 (received for review March 16, 2015) Loss of megafauna, an aspect of defaunation, can precipitate many megafauna loss, and if so, what does this loss imply for the future ecological changes over short time scales. We examine whether of ecosystems at risk for losing their megafauna today? megafauna loss can also explain features of lasting ecological state shifts that occurred as the Pleistocene gave way to the Holocene. We Approach compare ecological impacts of late-Quaternary megafauna extinction The late-Quaternary impact of losing 70–80% of the megafauna in five American regions: southwestern Patagonia, the Pampas, genera in the Americas (19) would be expected to trigger biotic northeastern United States, northwestern United States, and Berin- transitions that would be recognizable in the fossil record in at gia. We find that major ecological state shifts were consistent with least two respects. -

New Dinoflagellate Cyst and Acritarch Taxa from the Pliocene and Pleistocene of the Eastern North Atlantic (DSDP Site 610)

Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 6 (1): 101–117 Issued 22 February 2008 doi:10.1017/S1477201907002167 Printed in the United Kingdom C The Natural History Museum New dinoflagellate cyst and acritarch taxa from the Pliocene and Pleistocene of the eastern North Atlantic (DSDP Site 610) Stijn De Schepper∗ Cambridge Quaternary, Department of Geography, University of Cambridge, Downing Place, Cambridge CB2 3EN, United Kingdom Martin J. Head† Department of Earth Sciences, Brock University, 500 Glenridge Avenue, St. Catharines, Ontario L2S 3A1, Canada SYNOPSIS A palynological study of Pliocene and Pleistocene deposits from DSDP Hole 610A in the eastern North Atlantic has revealed the presence of several new organic-walled dinoflagellate cyst taxa. Impagidinium cantabrigiense sp. nov. first appeared in the latest Pliocene, within an inter- val characterised by a paucity of new dinoflagellate cyst species. Operculodinium? eirikianum var. crebrum var. nov. is mostly restricted to a narrow interval near the Mammoth Subchron within the Plio- cene (Piacenzian Stage) and may be a morphological adaptation to the changing climate at that time. An unusual morphotype of Melitasphaeridium choanophorum (Deflandre & Cookson, 1955) Harland & Hill, 1979 characterised by a perforated cyst wall is also documented. In addition, the stratigraphic utility of small acritarchs in the late Cenozoic of the northern North Atlantic region is emphasised and three stratigraphically restricted acritarchs Cymatiosphaera latisepta sp. nov., Lavradosphaera crista gen. et sp. nov. -

The Gelasian Stage (Upper Pliocene): a New Unit of the Global Standard Chronostratigraphic Scale

82 by D. Rio1, R. Sprovieri2, D. Castradori3, and E. Di Stefano2 The Gelasian Stage (Upper Pliocene): A new unit of the global standard chronostratigraphic scale 1 Department of Geology, Paleontology and Geophysics , University of Padova, Italy 2 Department of Geology and Geodesy, University of Palermo, Italy 3 AGIP, Laboratori Bolgiano, via Maritano 26, 20097 San Donato M., Italy The Gelasian has been formally accepted as third (and Of course, this consideration alone does not imply that a new uppermost) subdivision of the Pliocene Series, thus rep- stage should be defined to represent the discovered gap. However, the top of the Piacenzian stratotype falls in a critical point of the evo- resenting the Upper Pliocene. The Global Standard lution of Earth climatic system (i.e. close to the final build-up of the Stratotype-section and Point for the Gelasian is located Northern Hemisphere Glaciation), which is characterized by plenty in the Monte S. Nicola section (near Gela, Sicily, Italy). of signals (magnetostratigraphic, biostratigraphic, etc; see further on) with a worldwide correlation potential. Therefore, Rio et al. (1991, 1994) argued against the practice of extending the Piacenzian Stage up to the Pliocene-Pleistocene boundary and proposed the Introduction introduction of a new stage (initially “unnamed” in Rio et al., 1991), the Gelasian, in the Global Standard Chronostratigraphic Scale. This short report announces the formal ratification of the Gelasian Stage as the uppermost subdivision of the Pliocene Series, which is now subdivided into three stages (Lower, Middle, and Upper). Fur- The Gelasian Stage thermore, the Global Standard Stratotype-section and Point (GSSP) of the Gelasian is briefly presented and discussed. -

Formal Ratification of the Subdivision of the Holocene Series/ Epoch

Article 1 by Mike Walker1*, Martin J. Head 2, Max Berkelhammer3, Svante Björck4, Hai Cheng5, Les Cwynar6, David Fisher7, Vasilios Gkinis8, Antony Long9, John Lowe10, Rewi Newnham11, Sune Olander Rasmussen8, and Harvey Weiss12 Formal ratification of the subdivision of the Holocene Series/ Epoch (Quaternary System/Period): two new Global Boundary Stratotype Sections and Points (GSSPs) and three new stages/ subseries 1 School of Archaeology, History and Anthropology, Trinity Saint David, University of Wales, Lampeter, Wales SA48 7EJ, UK; Department of Geography and Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth University, Aberystwyth, Wales SY23 3DB, UK; *Corresponding author, E-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Earth Sciences, Brock University, 1812 Sir Isaac Brock Way, St. Catharines, Ontario LS2 3A1, Canada 3 Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Illinois, Chicago, Illinois 60607, USA 4 GeoBiosphere Science Centre, Quaternary Sciences, Lund University, Sölveg 12, SE-22362, Lund, Sweden 5 Institute of Global Change, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xian, Shaanxi 710049, China; Department of Earth Sciences, University of Minne- sota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA 6 Department of Biology, University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, New Brunswick E3B 5A3, Canada 7 Department of Earth Sciences, University of Ottawa, Ottawa K1N 615, Canada 8 Centre for Ice and Climate, The Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, Julian Maries Vej 30, DK-2100, Copenhagen, Denmark 9 Department of Geography, Durham University, Durham DH1 3LE, UK 10 -

GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE V

GSA GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE v. 4.0 CENOZOIC MESOZOIC PALEOZOIC PRECAMBRIAN MAGNETIC MAGNETIC BDY. AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE PICKS AGE . N PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE EON ERA PERIOD AGES (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) HIST HIST. ANOM. (Ma) ANOM. CHRON. CHRO HOLOCENE 1 C1 QUATER- 0.01 30 C30 66.0 541 CALABRIAN NARY PLEISTOCENE* 1.8 31 C31 MAASTRICHTIAN 252 2 C2 GELASIAN 70 CHANGHSINGIAN EDIACARAN 2.6 Lopin- 254 32 C32 72.1 635 2A C2A PIACENZIAN WUCHIAPINGIAN PLIOCENE 3.6 gian 33 260 260 3 ZANCLEAN CAPITANIAN NEOPRO- 5 C3 CAMPANIAN Guada- 265 750 CRYOGENIAN 5.3 80 C33 WORDIAN TEROZOIC 3A MESSINIAN LATE lupian 269 C3A 83.6 ROADIAN 272 850 7.2 SANTONIAN 4 KUNGURIAN C4 86.3 279 TONIAN CONIACIAN 280 4A Cisura- C4A TORTONIAN 90 89.8 1000 1000 PERMIAN ARTINSKIAN 10 5 TURONIAN lian C5 93.9 290 SAKMARIAN STENIAN 11.6 CENOMANIAN 296 SERRAVALLIAN 34 C34 ASSELIAN 299 5A 100 100 300 GZHELIAN 1200 C5A 13.8 LATE 304 KASIMOVIAN 307 1250 MESOPRO- 15 LANGHIAN ECTASIAN 5B C5B ALBIAN MIDDLE MOSCOVIAN 16.0 TEROZOIC 5C C5C 110 VANIAN 315 PENNSYL- 1400 EARLY 5D C5D MIOCENE 113 320 BASHKIRIAN 323 5E C5E NEOGENE BURDIGALIAN SERPUKHOVIAN 1500 CALYMMIAN 6 C6 APTIAN LATE 20 120 331 6A C6A 20.4 EARLY 1600 M0r 126 6B C6B AQUITANIAN M1 340 MIDDLE VISEAN MISSIS- M3 BARREMIAN SIPPIAN STATHERIAN C6C 23.0 6C 130 M5 CRETACEOUS 131 347 1750 HAUTERIVIAN 7 C7 CARBONIFEROUS EARLY TOURNAISIAN 1800 M10 134 25 7A C7A 359 8 C8 CHATTIAN VALANGINIAN M12 360 140 M14 139 FAMENNIAN OROSIRIAN 9 C9 M16 28.1 M18 BERRIASIAN 2000 PROTEROZOIC 10 C10 LATE -

Late Quaternary Changes in Climate

SE9900016 Tecnmcai neport TR-98-13 Late Quaternary changes in climate Karin Holmgren and Wibjorn Karien Department of Physical Geography Stockholm University December 1998 Svensk Kambranslehantering AB Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Co Box 5864 SE-102 40 Stockholm Sweden Tel 08-459 84 00 +46 8 459 84 00 Fax 08-661 57 19 +46 8 661 57 19 30- 07 Late Quaternary changes in climate Karin Holmgren and Wibjorn Karlen Department of Physical Geography, Stockholm University December 1998 Keywords: Pleistocene, Holocene, climate change, glaciation, inter-glacial, rapid fluctuations, synchrony, forcing factor, feed-back. This report concerns a study which was conducted for SKB. The conclusions and viewpoints presented in the report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily coincide with those of the client. Information on SKB technical reports fromi 977-1978 {TR 121), 1979 (TR 79-28), 1980 (TR 80-26), 1981 (TR81-17), 1982 (TR 82-28), 1983 (TR 83-77), 1984 (TR 85-01), 1985 (TR 85-20), 1986 (TR 86-31), 1987 (TR 87-33), 1988 (TR 88-32), 1989 (TR 89-40), 1990 (TR 90-46), 1991 (TR 91-64), 1992 (TR 92-46), 1993 (TR 93-34), 1994 (TR 94-33), 1995 (TR 95-37) and 1996 (TR 96-25) is available through SKB. Abstract This review concerns the Quaternary climate (last two million years) with an emphasis on the last 200 000 years. The present state of art in this field is described and evaluated. The review builds on a thorough examination of classic and recent literature (up to October 1998) comprising more than 200 scientific papers. -

2.11 Paleontological Resources

2.11 Paleontological Resources 2.11 Paleontological Resources This section discusses existing conditions and potential impacts to paleontological resources resulting from implementation of the proposed project. The analysis is based on a review of existing paleontological resources; technical data; and applicable laws, regulations, and guidelines, and identifies measures to mitigate impacts to paleontological resources. Comments received in response to the Notice of Preparation (NOP) did not pertain to paleontological resources. A copy of the NOP and comment letters received in response to the NOP is included in Appendix A of this EIR. 2.11.1 Existing Conditions Paleontological resources are the remains and/or traces of prehistoric life, exclusive of remains from human activities, and include the localities where fossils were collected and the sedimentary rock formations from which they were obtained/derived. The defining character of fossils is their geologic age. Fossils or fossil deposits are generally regarded as older than 10,000 years, the generally accepted temporal boundary marking the end of the last Late Pleistocene glacial event and the beginning of the current period of climatic amelioration of the Holocene (County of San Diego 2009). A unique paleontological resource is any fossil or assemblage of fossils, or paleontological resource site or formation that meets any one of the following criteria (County of San Diego 2009): The best example of its kind locally or regionally; Illustrates a paleontological or evolutionary principle -

Mid-Pliocene Onset of Quaternary-Style Climates Mid-Pliocene Shifts in Ocean Overturning M

Clim. Past Discuss., 5, 251–285, 2009 www.clim-past-discuss.net/5/251/2009/ Climate of the Past CPD © Author(s) 2009. This work is distributed under Discussions 5, 251–285, 2009 the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Climate of the Past Discussions is the access reviewed discussion forum of Climate of the Past Mid-Pliocene onset of Quaternary-style climates Mid-Pliocene shifts in ocean overturning M. Sarnthein et al. circulation and the onset of ∗ Title Page Quaternary-style climates Abstract Introduction M. Sarnthein1,2, M. Prange3, A. Schmittner4, B. Schneider1, and M. Weinelt1 Conclusions References 1Institute for Geosciences, University of Kiel, 24098 Kiel, Germany Tables Figures 2Institute for Geology and Paleontology, University of Innsbruck, 6020, Austria 3 MARUM Center for Marine Environmental Sciences and Faculty of Geosciences, J I University of Bremen, 28334 Bremen, Germany 4College of Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University, J I Corvallis OR 97331-5503, USA Back Close Received: 11 December 2008 – Accepted: 11 December 2008 – Published: 26 January 2009 Full Screen / Esc Correspondence to: M. Sarnthein ([email protected]) Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. Printer-friendly Version Interactive Discussion ∗Invited contribution by M. Sarnthein, EGU Milutin Milankovic Medal winner 2006 251 Abstract CPD A major tipping point of Earth’s history occurred during the mid-Pliocene: the onset of major Northern Hemisphere Glaciation (NHG) and pronounced, Quaternary-style 5, 251–285, 2009 cycles of glacial-to-interglacial climates, that contrast with more uniform climates over 5 most of the preceding Cenozoic, that and continue until today.