Rewriting the Rules: Chinaʼs New Economic Power, and Its Effect on Global Governance Decisions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluation of Public Financial Management Reform in Burkina Faso 2001–2010 Final Country Case Study Report

Evaluation of Public Financial Management Reform Evaluation Public of Financial Management Reform 2012:10 Joint Evaluation in Burkina Faso, 2001–2010 Final Country Case Study Report Andrew Lawson Where and why do Public Financial Management (PFM) reforms succeed? Where and how does donor support to Mailan Chiche PFM reform contribute most effectively to results? To answer these questions, an evaluation of PFM reforms has Idrissa Ouedraogo been carried out, primarily based on country studies of Burkina Faso, Ghana and Malawi. An international quantitative study and a literature review were also undertaken. This report presents the findings of the study in Burkina Faso The findings from the three country studies are summarised in a separate synthesis report, concluding that results tend to be good when there is a strong commitment at both political and technical levels, when reform designs and implementation models are well tailored to the context and when strong, government-led coordina- Evaluation of Public tion arrangements are in place to monitor and guide reforms. Donor funding for PFM reform has been effective in those countries where the context and mechanisms were right for success, and where external funding was focused on the Government’s own reform programme. The Financial Management Reform willingness of some Governments to fund PFM reforms directly shows that external funding may not be the deciding factor, however. Donor pressure to develop comprehensive PFM reform plans has been a positive influence in countries receiving Budget Support, but attempts to overtly influence either the pace or the content of in Burkina Faso, 2001–2010 PFM reforms were found to be ineffective and often counter-productive. -

Circular Economy in Africa-EU Cooperation

Circular Economy in Africa-EU Cooperation Country Report Senegal Written by November - 2020 EUROPEAN COMMISSION Directorate-General for Environment Directorate F – Global Sustainable Development Unit F2 - Bilateral & Regional Environmental Cooperation Contact: Gaëtan Ducroux E-mail: [email protected] European Commission B-1049 Brussels EUROPEAN COMMISSION Circular Economy in Africa-EU Cooperation Country Report Senegal Authors: Bonnaire, S.M.; Jagot, J.; Spinazzé, C.; Potgieter, J.E.; Rajput, J.; Hemkhaus, M.; Ahlers, J.; Koehler, J.; Van Hummelen, S. & McGovern, M. Acknowledgements We acknowledge the valuable contribution of several co-workers from within the four participating institutions, as well as the feedback received from DG Environment and other DG’s of the European Commission as well as the Members of the EU delegation to Senegal. Preferred citation Bonnaire, S.M.; Jagot, J.; Spinazzé, C. (2020) Circular economy in the Africa-EU cooperation - Country report for Senegal. Country report under EC Contract ENV.F.2./ETU/2018/004 Project: “ “Circular Economy in Africa-Eu cooperation”, Trinomics B.V., ACEN, adelphi Consult GmbH and Cambridge Econometrics Ltd. In association with: LEGAL NOTICE This document has been prepared for the European Commission however it reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://www.europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2020 PDF ISBN 978-92-76-26828-4 doi:10.2779/042060 KH-06-20-056-EN-N © European Union, 2020 The Commission’s reuse policy is implemented by Commission Decision 2011/833/EU of 12 December 2011 on the reuse of Commission documents (OJ L 330, 14.12.2011, p. -

Pdg Groupe Crestone

Bimestriel d’informations du Port Autonome de Dakar N°24 Avril - Mai 2019 JOURNÉES PORTUAIRES ET MARITIMES Aboubacar Sedikh BEYE : « la réussite de la vision stratégique demande l’accompagnement de tous » MONSIEUR SOURAKHATA TIRERA PDG GROUPE CRESTONE « En 2018 il y a eu 480.000 conteneurs en provenance de YIWU dont 13000 pour le Sénégal » « Appui aux fédérations sportives, Le PAD reçoit une délégation de Salon International de le PAD en modèle » la ville YIWU en Chine l’Agriculture de paris (sia) 2019 "Support to the sport organiza- DAP (Dakar Autonomous Port) « Le PAD toujours au tions, PAD (Dakar Autonomous welcomes a delegation from rendez-vous » Port) as a model’’ Yiwu city in China “ PAD is always present” Sommaire Contents EDITO : ............................................................. 4-5 EDITOR’S LETTER : ....................................................... 4-5 la santé par le sport Health through sport TELEX : ................................................................... 6 TELEX : .......................................................................................... 6 Appui à la politique sportive A support to the sport policy ACTUALITES : ............................................7...18 CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS : .............................7...18 - Visite au port de Dakar - A Visit at the port of Dakar by the des autorités de la ville de Yiwu authorities of Yiwu town - 1ére Edition des Journées Portuaires - First Edition of naval and port days (NPD) et Maritimes (J.P.M) - Participation of the port to the -

Senegal Country Development Cooperation Strategy Original Dates: April 2, 2012 – April 2, 2017 Extended Through: April 2, 2019 Extended On: May 4, 2017

SENEGAL COUNTRY DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION STRATEGY ORIGINAL DATES: APRIL 2, 2012 – APRIL 2, 2017 EXTENDED THROUGH: APRIL 2, 2019 EXTENDED ON: MAY 4, 2017 May 2017 This publication was produced by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by USAID/Senegal. SENEGAL COUNTRY DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION STRATEGY ORIGINAL DATES: APRIL 2, 2012 – APRIL 2, 2017 EXTENDED THROUGH: APRIL 2, 2019 EXTENDED ON: MAY 4, 2017 1 CONTENTS CONTENTS ................................................................................................................................................. 2 ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................................................ 3 1. DEVELOPMENT CONTEXT, CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES ....................................... 5 2. USAID/SENEGAL DEVELOPMENT OBJECTIVES ........................................................................ 10 3. MONITORING, EVALUATION AND LEARNING ........................................................................ 39 ANNEX A. M&E TABLE .......................................................................................................................... 43 2 ACRONYMS Abbreviations and acronyms have been kept to a minimum in the text of this document. Where abbreviations or acronyms have been used, they are accompanied by their full expression the first time they appear, unless they are commonly used and generally understood abbreviations such as NGO, kg., etc. However, in order to -

Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso 2016 Country Review http://www.countrywatch.com Table of Contents Chapter 1 1 Country Overview 1 Country Overview 2 Key Data 3 Burkina Faso 4 Africa 5 Chapter 2 7 Political Overview 7 History 8 Political Conditions 9 Political Risk Index 38 Political Stability 52 Freedom Rankings 68 Human Rights 80 Government Functions 82 Government Structure 84 Principal Government Officials 95 Leader Biography 105 Leader Biography 105 Foreign Relations 117 National Security 120 Defense Forces 123 Chapter 3 125 Economic Overview 125 Economic Overview 126 Nominal GDP and Components 128 Population and GDP Per Capita 130 Real GDP and Inflation 131 Government Spending and Taxation 132 Money Supply, Interest Rates and Unemployment 133 Foreign Trade and the Exchange Rate 134 Data in US Dollars 135 Energy Consumption and Production Standard Units 136 Energy Consumption and Production QUADS 138 World Energy Price Summary 139 CO2 Emissions 140 Agriculture Consumption and Production 141 World Agriculture Pricing Summary 143 Metals Consumption and Production 144 World Metals Pricing Summary 146 Economic Performance Index 147 Chapter 4 159 Investment Overview 159 Foreign Investment Climate 160 Foreign Investment Index 162 Corruption Perceptions Index 175 Competitiveness Ranking 187 Taxation 196 Stock Market 196 Partner Links 197 Chapter 5 198 Social Overview 198 People 199 Human Development Index 203 Life Satisfaction Index 206 Happy Planet Index 218 Status of Women 227 Global Gender Gap Index 229 Culture and Arts 239 Etiquette 240 Travel Information -

INSTITUTIONAL RESILIENCE and INFORMALITY the Case of Land Rights Mechanisms in Greater Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso

INSTITUTIONAL RESILIENCE AND INFORMALITY The Case of Land Rights Mechanisms in Greater Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Julie Touber Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Julie Touber All rights reserved ABSTRACT INSTITUTIONAL RESILIENCE AND INFORMALITY The Case of Land Rights Mechanisms in Greater Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Julie Touber Land informality, or the absence of clear property rights, has been identified as a strong cause for lower economic development performance. In Africa, despite the presence of a formal institutional setting of property rights and established laws, the practice of land rights has favored a persistent informal institutional regime. This dissertation addresses the reasons for the persistence of land informality in the presence of formal laws in the case of Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso. Using process tracing, I dissect the processes of land conflict resolutions within the formal and informal institutions in order to pinpoint reasons for such prolong informality. I identify a very coherent and organized institutional set within the customary institutions, and the ambiguous relationship these institutions have with formal institutions. The inability of the formal institutions to resolve the informality issue is not the result of incompetence; it is the result of survival mechanisms from both the informal and formal institutions. Informality is the effect of the layered institutional setting and persists because of the resilience of survival mechanisms. TABLE OF CONTENT List of Figures iv List of Tables v Introduction 2 PART 1: FRAMING THE THEORETICAL AND METHODOLOGICAL CONTEXT 8 Chapter 1: The Reading Frames Debunking Concepts of Tradition and Modernity in the African Context 9 1.1. -

Burkina Faso

Co-funded by the Internal Security Fund of the European Union LET4CAP Law Enforcement Training for Capacity Building BURKINA FASO Downloadable Country Booklet DL. 2.5 (Version 1.2) 1 Dissemination level: PU Let4Cap Grant Contract no.: HOME/ 2015/ISFP/AG/LETX/8753 Start date: 01/11/2016 Duration: 33 months Dissemination Level PU: Public X PP: Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission) RE: Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission) Revision history Rev. Date Author Notes 1.0 18/05/2018 Ce.S.I. Overall structure and first draft 1.1 25/06/2018 Ce.S.I. Second draft 1.2 30/11/2018 Ce.S.I. Final version LET4CAP_WorkpackageNumber 2 Deliverable_2.5 VER WorkpackageNumber 2 Deliverable 2.5 Deliverable Downloadable country booklets VER 1.2 2 BURKINA FASO Country Information Package 3 This Country Information Package has been prepared by Alessandra Giada Dibenedetto – Marco Di Liddo – Francesca Manenti – Lorenzo Marinone Ce.S.I. – Centre for International Studies Within the framework of LET4CAP and with the financial support to the Internal Security Fund of the EU LET4CAP aims to contribute to more consistent and efficient assistance in law enforcement capacity building to third countries. The Project consists in the design and provision of training interventions drawn on the experience of the partners and fine-tuned after a piloting and consolidation phase. © 2018 by LET4CAP…. All rights reserved. 4 Table of contents 1. Country Profile 1.1 Country in Brief 1.2 Modern and Contemporary History of Burkina Faso 1.3 Geography 1.4 Territorial and Administrative Units 1.5 Population 1.6 Ethnic Groups, Languages, Religion 1.7 Health 1.8 Education and Literacy 1.9 Country Economy 2. -

The Club of Ports Friends

THE CLUB OF PORTS FRIENDS Mr. Jean-Louis Osso Mr. Peder Sondergaard Mr. Alberto Bengue Chairman of the Board CEO Africa/Middle-East Administrator Autonomous Port of Pointe-Noire APM Terminals Port of Luanda, Angola Congo Mr. Pottengal Mukundan Mrs. Mariam Aweis Jama Mr. Youssef Imghi Director Minister of Ports & Marine Director General International Maritime Bureau Transports, Somalia Tanger Med Engineering, Morocco Mr. Arjuna Ranatunga Mr. Ahmed Bin Ali Al Mohannadi Mr. Peter Brady Minister of Ports & Shipping Director General Director General Sri Lanka General Authority of Customs Maritime Authority, Jamaica Qatar Mr. Dakuku Peterside Mr. Paul Graaf Mr. Pierre Reteno Ndiaye Director General & CEO Director Europe, Middle East Chairman Nigerian Maritime Administration Office des Ports et Rades and Africa & Safety Agency Lloyd’s Register du Gabon Mr. Hanounaye Gounoko Mrs. Aicha Dabar Guelleh Mr. Omran Radhi Thani President MP & Chairperson Committee on General Director National Port Authority Foreign Affairs, National National Port Authority Cameroon Assembly, Djibouti Iraq Mr. Mircea Ciopraga Mr. Stefaan Depypere Mr. Alhaji Worroh Jalloh Secretary General, Transport Director Executive Director, Sierra Corridor Europe-Caucasus-Asia DG Maritime Affairs & Fisheries Leone Maritime Intergovernmental Commission European Commission Administration Mr. Thomas Schmid Mr. Gichiri Ndua Mr. Jianhua Zhong Special Representative for African Director Africa Managing Director Affairs Ministry of Foreign Affairs Airbus Defense & Space Kenya Ports Authority P.R.China (EADS) Mr. Walter Semianiw Mrs. Fatoumata Cisse Mr. Silvio Ferrando Commander of Canada Command Director General International Business Manager Ministry of National Defence, Canada Société Navale Guinéenne Port Authority of Genoa, Italy Mr. Gordan Grlic-Radman Mr. Serge Marigliano Mrs. -

Progress Towards Regional Integration in West Africa

ECA-WA 2015 An assessment of progress towards regional integration in the ECOWAS Sub-Regional Office Economic Community for West Africa of West African States ECA-WA/NREC/2015/03 Original text: French AN ASSESSMENT OF PROGRESS TOWARDS REGIONAL INTEGRATION IN THE ECONOMIC COMMUNITY OF WEST AFRICAN STATES SINCE ITS INCEPTION MAY 2015 1 ECA-WA 2015 An assessment of progress towards regional integration in the ECOWAS CONTENT LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................................................ 5 LIST OF CHARTS ........................................................................................................................ 6 LIST OF BOXES ........................................................................................................................... 6 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS............................................................................................ 7 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................... 10 FOREWORD .............................................................................................................................. 11 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ 14 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 19 I. RATIONALE FOR REGIONAL INTEGRATION IN -

Blaise Compaoré

Blaise Compaoré Burkina Faso, Presidente de la junta militar (1987-1991) y de la República (1991-2014) Duración del mandato: 15 de Octubre de 1987 - de de Nacimiento: Ziniaré, provincia de Oubritenga, región de Plateau-Central, 03 de Febrero de 1951 Partido político: Congreso por la Democracia y el Progreso (CDP) Profesión : Militar Resumen En Burkina Faso, un masivo y fulminante levantamiento popular puso término el último día de octubre de 2014 a la larga presidencia de Blaise Compaoré, en el poder desde 1987. La revuelta de los airados ciudadanos burkineses, saldada con la renuncia y fuga del dirigente, y la toma del Ejecutivo por el Ejército bajo la promesa de una transición consensuada con los partidos de la oposición, tuvo como espoleta el intento abusivo por Compaoré de, repitiendo la maniobra estrenada en 2000, enmendar la Constitución para poder optar a un nuevo mandato electoral, que habría de ser el quinto consecutivo tras los ganados en las urnas en 1991, 1998, 2005 y 2010. Sin embargo, la súbita Primavera Burkinesa, expresión de un malestar general incubado por largo tiempo en este país subsaheliano hundido en los rankings mundiales de desarrollo humano, se estaba gestando al menos desde las protestas de 2011. Con la caída de Compaoré, autócrata de maneras gentiles y discurso benigno que dosificaba la represión de los detractores más molestos (muerte del periodista Norbert Zongo en 1998) y que cultivaba con destreza la respetabilidad internacional, desaparece uno de los más veteranos e intrigantes hombres fuertes del continente negro, en su caso aliado privilegiado de Francia y Estados Unidos, así como "buen alumno" del FMI y el Banco Mundial. -

Fast-Tracking Transformation

AFRICA’S PORTS: FAST-TRACKING TRANSFORMATION The modernisation of Africa’s port sector has yielded some spectacular results, with a number of global champions – such as Tanger Med, Port Said and Djibouti – emerging on the scene. What should public and private decision-makers do to speed up the process even more? October 2020 Foreword Frédéric Maury - AFRICA CEO FORUM Amaury de Féligonde - OKAN PARTNERS Following on the success of the 2019 African logistics processes, digitalisation and container terminals just sector report, “Time for Revolution”, the AFRICA CEO as other types of terminals (bulk, roll-on/roll-off, FORUM (which today has established itself as the etc.). In 2019, the new Tanger Med 2 terminal opened largest international conference dedicated to Africa’s in Morocco. Major infrastructure projects are in the private sector), in partnership with Okan (an Africa- process of being completed in sub-Saharan Africa, focused strategy consulting and financial advisory including TC2 in Abidjan (1.5 million TEU), Lekki in firm), has decided to repeat the experience, centring Nigeria (up to 2.7 million TEU over time) and MPS2 in its attention on ports this year. Tema (3.5 million TEU over time). In fact, the port sector has a special significance in Africa since more than 80% of the continent’s trade Through an in-depth study of these cases and passes through ports. The modernisation of port the multiple challenges that hinder change in this infrastructure assets is a fundamental component strategic sector, the AFRICA CEO FORUM and Okan of Africa’s transformation, competitiveness, have come up with the six recommendations below. -

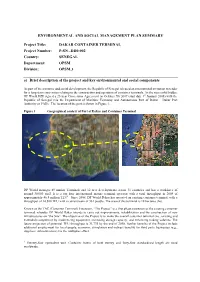

SENEGAL Department: OPSM Division: OPSM.3 A) Brief Description of the Project and Key Environmental and Social Components

ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN SUMMARY Project Title: DAKAR CONTAINER TERMINAL Project Number: P-SN –DD0-002 Country: SENEGAL Department: OPSM Division: OPSM.3 a) Brief description of the project and key environmental and social components As part of its economic and social development, the Republic of Senegal released an international invitation to tender for a long-term concession relating to the construction and operation of container terminals. As the successful bidder, DP World FZE signed a 25-year Concession Agreement on October 7th 2007 (start date 1st January 2008) with the Republic of Senegal (via the Department of Maritime Economy and Autonomous Port of Dakar – Dakar Port Authority or PAD). The location of the port is shown in Figure 1. Figure 1 Geographical context of Port of Dakar and Container Terminal DP World manages 49 marine Terminals and 12 new developments across 31 countries and has a workforce of around 30,000 staff. It is a top four international marine terminal operator with a total throughput in 2008 of approximately 46.8 million TEU1. Since 2008, DP World Dakar has operated an existing container terminal, with a throughput of 14,500 TEU with a current team of 361 people. The area of this terminal is 18 hectares (ha). Known as the TAC (Container Terminal) Extension, “The Project” is a first phase extension of the existing container terminal, whereby DP World Dakar intends to carry out improvements, rehabilitation and the construction of new infrastructures on “the Site”. The objective of the Project is to make the overall container terminal (i.e., existing and extended) competitive by modernizing equipment, increasing storage capacity, and enhancing trading volumes.