Progress Towards Regional Integration in West Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Circular Economy in Africa-EU Cooperation

Circular Economy in Africa-EU Cooperation Country Report Senegal Written by November - 2020 EUROPEAN COMMISSION Directorate-General for Environment Directorate F – Global Sustainable Development Unit F2 - Bilateral & Regional Environmental Cooperation Contact: Gaëtan Ducroux E-mail: [email protected] European Commission B-1049 Brussels EUROPEAN COMMISSION Circular Economy in Africa-EU Cooperation Country Report Senegal Authors: Bonnaire, S.M.; Jagot, J.; Spinazzé, C.; Potgieter, J.E.; Rajput, J.; Hemkhaus, M.; Ahlers, J.; Koehler, J.; Van Hummelen, S. & McGovern, M. Acknowledgements We acknowledge the valuable contribution of several co-workers from within the four participating institutions, as well as the feedback received from DG Environment and other DG’s of the European Commission as well as the Members of the EU delegation to Senegal. Preferred citation Bonnaire, S.M.; Jagot, J.; Spinazzé, C. (2020) Circular economy in the Africa-EU cooperation - Country report for Senegal. Country report under EC Contract ENV.F.2./ETU/2018/004 Project: “ “Circular Economy in Africa-Eu cooperation”, Trinomics B.V., ACEN, adelphi Consult GmbH and Cambridge Econometrics Ltd. In association with: LEGAL NOTICE This document has been prepared for the European Commission however it reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://www.europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2020 PDF ISBN 978-92-76-26828-4 doi:10.2779/042060 KH-06-20-056-EN-N © European Union, 2020 The Commission’s reuse policy is implemented by Commission Decision 2011/833/EU of 12 December 2011 on the reuse of Commission documents (OJ L 330, 14.12.2011, p. -

Pdg Groupe Crestone

Bimestriel d’informations du Port Autonome de Dakar N°24 Avril - Mai 2019 JOURNÉES PORTUAIRES ET MARITIMES Aboubacar Sedikh BEYE : « la réussite de la vision stratégique demande l’accompagnement de tous » MONSIEUR SOURAKHATA TIRERA PDG GROUPE CRESTONE « En 2018 il y a eu 480.000 conteneurs en provenance de YIWU dont 13000 pour le Sénégal » « Appui aux fédérations sportives, Le PAD reçoit une délégation de Salon International de le PAD en modèle » la ville YIWU en Chine l’Agriculture de paris (sia) 2019 "Support to the sport organiza- DAP (Dakar Autonomous Port) « Le PAD toujours au tions, PAD (Dakar Autonomous welcomes a delegation from rendez-vous » Port) as a model’’ Yiwu city in China “ PAD is always present” Sommaire Contents EDITO : ............................................................. 4-5 EDITOR’S LETTER : ....................................................... 4-5 la santé par le sport Health through sport TELEX : ................................................................... 6 TELEX : .......................................................................................... 6 Appui à la politique sportive A support to the sport policy ACTUALITES : ............................................7...18 CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS : .............................7...18 - Visite au port de Dakar - A Visit at the port of Dakar by the des autorités de la ville de Yiwu authorities of Yiwu town - 1ére Edition des Journées Portuaires - First Edition of naval and port days (NPD) et Maritimes (J.P.M) - Participation of the port to the -

Senegal Country Development Cooperation Strategy Original Dates: April 2, 2012 – April 2, 2017 Extended Through: April 2, 2019 Extended On: May 4, 2017

SENEGAL COUNTRY DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION STRATEGY ORIGINAL DATES: APRIL 2, 2012 – APRIL 2, 2017 EXTENDED THROUGH: APRIL 2, 2019 EXTENDED ON: MAY 4, 2017 May 2017 This publication was produced by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by USAID/Senegal. SENEGAL COUNTRY DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION STRATEGY ORIGINAL DATES: APRIL 2, 2012 – APRIL 2, 2017 EXTENDED THROUGH: APRIL 2, 2019 EXTENDED ON: MAY 4, 2017 1 CONTENTS CONTENTS ................................................................................................................................................. 2 ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................................................ 3 1. DEVELOPMENT CONTEXT, CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES ....................................... 5 2. USAID/SENEGAL DEVELOPMENT OBJECTIVES ........................................................................ 10 3. MONITORING, EVALUATION AND LEARNING ........................................................................ 39 ANNEX A. M&E TABLE .......................................................................................................................... 43 2 ACRONYMS Abbreviations and acronyms have been kept to a minimum in the text of this document. Where abbreviations or acronyms have been used, they are accompanied by their full expression the first time they appear, unless they are commonly used and generally understood abbreviations such as NGO, kg., etc. However, in order to -

The Club of Ports Friends

THE CLUB OF PORTS FRIENDS Mr. Jean-Louis Osso Mr. Peder Sondergaard Mr. Alberto Bengue Chairman of the Board CEO Africa/Middle-East Administrator Autonomous Port of Pointe-Noire APM Terminals Port of Luanda, Angola Congo Mr. Pottengal Mukundan Mrs. Mariam Aweis Jama Mr. Youssef Imghi Director Minister of Ports & Marine Director General International Maritime Bureau Transports, Somalia Tanger Med Engineering, Morocco Mr. Arjuna Ranatunga Mr. Ahmed Bin Ali Al Mohannadi Mr. Peter Brady Minister of Ports & Shipping Director General Director General Sri Lanka General Authority of Customs Maritime Authority, Jamaica Qatar Mr. Dakuku Peterside Mr. Paul Graaf Mr. Pierre Reteno Ndiaye Director General & CEO Director Europe, Middle East Chairman Nigerian Maritime Administration Office des Ports et Rades and Africa & Safety Agency Lloyd’s Register du Gabon Mr. Hanounaye Gounoko Mrs. Aicha Dabar Guelleh Mr. Omran Radhi Thani President MP & Chairperson Committee on General Director National Port Authority Foreign Affairs, National National Port Authority Cameroon Assembly, Djibouti Iraq Mr. Mircea Ciopraga Mr. Stefaan Depypere Mr. Alhaji Worroh Jalloh Secretary General, Transport Director Executive Director, Sierra Corridor Europe-Caucasus-Asia DG Maritime Affairs & Fisheries Leone Maritime Intergovernmental Commission European Commission Administration Mr. Thomas Schmid Mr. Gichiri Ndua Mr. Jianhua Zhong Special Representative for African Director Africa Managing Director Affairs Ministry of Foreign Affairs Airbus Defense & Space Kenya Ports Authority P.R.China (EADS) Mr. Walter Semianiw Mrs. Fatoumata Cisse Mr. Silvio Ferrando Commander of Canada Command Director General International Business Manager Ministry of National Defence, Canada Société Navale Guinéenne Port Authority of Genoa, Italy Mr. Gordan Grlic-Radman Mr. Serge Marigliano Mrs. -

Rewriting the Rules: Chinaʼs New Economic Power, and Its Effect on Global Governance Decisions

Rewriting the Rules: Chinaʼs New Economic Power, and its Effect on Global Governance Decisions Dorothy J. Heebner A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN March 25, 2011 Advised by Professor Barbara Koremenos TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract" 4 Acknowledgments" 5 Index of Acronyms" 6 Introduction" 8 CHAPTER 1: A HISTORY OF INFLUENCE THROUGH ECONOMIC POWER" 14 A history of economic power! 15 Influence through economic power! 18 China"s rise to prominence! 28 China"s Rules! 33 CHAPTER 2: A POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC HISTORY OF THE SIX CASE COUNTRIES" 38 Case study selection! 38 Case Study History! 41 Angola! 43 Sudan! 48 South Africa! 49 Burkina Faso! 51 Senegal! 51 Nigeria! 51 CHAPTER 3: CHINA!S INVOLVEMENT" 62 CHAPTER FOUR-CHINA!S EFFECT" 72 Economic Decisionmaking Changes: Media Reporting! 74 2 South Africa! 75 Angola! 79 Sudan! 85 Nigeria! 88 Senegal! 95 Burkina Faso! 97 Ideological Policy Changes: Human Rights Respect! 97 South Africa! 104 Angola! 106 Sudan! 108 Nigeria! 111 Senegal! 112 Burkina Faso! 115 A Confounding Factor: The Endogeneity Problem! 117 CONCLUSION" 119 Appendix" 122 Data table! 122 Exports and Imports! 122 Aid! 124 Foreign Direct Investment and Use of IMF Credit! 126 3 Abstract ! The domestic policy of any country cannot be explained without accounting for economic ties with the rest of the world. Countries trade with each other, seek aid from other countries and institutions, provide and accept foreign investment, and interact economically in other ways to gain economic utility. -

Fast-Tracking Transformation

AFRICA’S PORTS: FAST-TRACKING TRANSFORMATION The modernisation of Africa’s port sector has yielded some spectacular results, with a number of global champions – such as Tanger Med, Port Said and Djibouti – emerging on the scene. What should public and private decision-makers do to speed up the process even more? October 2020 Foreword Frédéric Maury - AFRICA CEO FORUM Amaury de Féligonde - OKAN PARTNERS Following on the success of the 2019 African logistics processes, digitalisation and container terminals just sector report, “Time for Revolution”, the AFRICA CEO as other types of terminals (bulk, roll-on/roll-off, FORUM (which today has established itself as the etc.). In 2019, the new Tanger Med 2 terminal opened largest international conference dedicated to Africa’s in Morocco. Major infrastructure projects are in the private sector), in partnership with Okan (an Africa- process of being completed in sub-Saharan Africa, focused strategy consulting and financial advisory including TC2 in Abidjan (1.5 million TEU), Lekki in firm), has decided to repeat the experience, centring Nigeria (up to 2.7 million TEU over time) and MPS2 in its attention on ports this year. Tema (3.5 million TEU over time). In fact, the port sector has a special significance in Africa since more than 80% of the continent’s trade Through an in-depth study of these cases and passes through ports. The modernisation of port the multiple challenges that hinder change in this infrastructure assets is a fundamental component strategic sector, the AFRICA CEO FORUM and Okan of Africa’s transformation, competitiveness, have come up with the six recommendations below. -

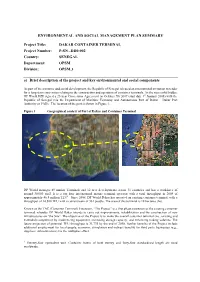

SENEGAL Department: OPSM Division: OPSM.3 A) Brief Description of the Project and Key Environmental and Social Components

ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN SUMMARY Project Title: DAKAR CONTAINER TERMINAL Project Number: P-SN –DD0-002 Country: SENEGAL Department: OPSM Division: OPSM.3 a) Brief description of the project and key environmental and social components As part of its economic and social development, the Republic of Senegal released an international invitation to tender for a long-term concession relating to the construction and operation of container terminals. As the successful bidder, DP World FZE signed a 25-year Concession Agreement on October 7th 2007 (start date 1st January 2008) with the Republic of Senegal (via the Department of Maritime Economy and Autonomous Port of Dakar – Dakar Port Authority or PAD). The location of the port is shown in Figure 1. Figure 1 Geographical context of Port of Dakar and Container Terminal DP World manages 49 marine Terminals and 12 new developments across 31 countries and has a workforce of around 30,000 staff. It is a top four international marine terminal operator with a total throughput in 2008 of approximately 46.8 million TEU1. Since 2008, DP World Dakar has operated an existing container terminal, with a throughput of 14,500 TEU with a current team of 361 people. The area of this terminal is 18 hectares (ha). Known as the TAC (Container Terminal) Extension, “The Project” is a first phase extension of the existing container terminal, whereby DP World Dakar intends to carry out improvements, rehabilitation and the construction of new infrastructures on “the Site”. The objective of the Project is to make the overall container terminal (i.e., existing and extended) competitive by modernizing equipment, increasing storage capacity, and enhancing trading volumes. -

FRENCH LEGAL ASPECTS of PORT MANAGEMENT Report by the UNCTAD S

Distr. GENERAL UNCTAD/SHIP/639 11 February 1993 ENGLISH Original: FRENCH LEGAL ASPECTS OF PORT MANAGEMENT Report by the UNCTAD secretariat GE.93-50421 (E) -2- CONTENTS Page FOREWORD ............................... 8 INTRODUCTION ........... ................. 10 CHAPTER I. THE SOURCES OF LAW AND THE NATURE OF PORT LAW ..... 12 The legal system in force in the statute-law countries and in the French-speaking countries in particular ... 12 I. The sources of internal law ............ 12 A. The laws and regulations ........... 12 (a) The hierarchy of laws and regulations . 13 (b) Specific laws and regulations concerning port activities ............. 13 (c) Laws and regulations not specific to port activities ................ 16 B. Jurisprudence ................. 16 C. Doctrine ................... 16 II. The sources of international law ......... 16 III. The nature of port law .............. 17 A. Relations governed by public law ....... 17 B. Relations governed by private law ....... 18 C. Relations governed by public and private law . 19 D. Importance of the distinction between legal regimes .................... 19 The common-law system ...... ........... 19 A. British constitutional law .......... 19 B. The organization of the courts in the United Kingdom ................ 20 (a) In civil matters ............. 20 (b) In criminal matters ........... 20 -3- CONTENTS (continued) Page (c) In administrative matters ........ 21 (d) Administrative law in the United Kingdom . 21 Conclusion............ ........... 22 CHAPTER II. INSTITUTIONAL ASPECTS: THE LEGAL REGIME OF PORTS . 23 I. The concept of a seaport II. The legal regime of seaport management ...... 25 A. Ports under centralized management ...... 27 B. Ports under decentralized management and autonomous ports ............... 28 (a) Decentralization with regard to ports . 28 (b) The regime of the autonomous seaport authority ............... -

Global Local Forum 2013

Global local forum 2013 Le dialogue des territoires La revue Global local forum est consacrée aux nouvelles approches territoriales du développement. Issue des travaux du Global local forum, des contributions de GlGloobalbal locallocal fforumorum ses membres, d’experts internationaux et de praticiens des politiques territoriales, elle rassemble des points de vue, analyses et illustrations concrètes sur les formes LeLe dialogue dialogue desdes territoiresterritoires innovantes de développement des territoires. Le dossier central de cette édition 2013 a pour thème la coopération transfrontalière. Facteur d’intégration régionale, levier pour le développement et la paix, la coopération transfrontalière est un sujet central et ne concerne pas seulement la périphérie des Etats ou les seules populations frontalières. Sur tous les continents, elle est au service du développement et de l’intégration régionale dans le dialogue des territoires. Elle permet concrètement l’exploitation en commun 2013 des ressources, la gestion partenariale de services accessibles sans discrimination d’appartenance nationale et la circulation des personnes. Dans le cadre de la coopération décentralisée entre pouvoirs locaux du Nord et La coopération transfrontalière du Sud que promeut Global local forum, les élus et responsables territoriaux mettent en partage leurs expériences et les enseignements réussis de coopération transfrontalière. Afrique, Amérique latine, Asie du Sud-Est ou Europe, partout en Le dialogue des territoires levier pour le développement et la paix -

Trade-Watch Africa Issue 61 | June 2016

TRADE-WATCH AFRICA ISSUE 61 | JUNE 2016 ARE YOU READY? IMO CONTAINER WEIGHT RULES COME INTO FORCE JULY 1ST Full Story On Page 5 AFRICATRADE-WATCH ISSUE 61 | JUNE 2016 Contents 03 | African Group News Are You Ready? IMO Container Weight Rules Come Into Force July 1st / CMA CGM Unveils Online VGM Submission Platform; Free, Easy To Use & Highly Visible / CMA CGM Strengthens FEMEX Service / CMA CGM Your Expert In Project Shipments / CMA CGM HO Hosts Dakar Port Delegation / Staff Decorated By The Ivorian Minister of Employment / CMA CGM Malawi Holds Customer Reception /CMA CGM Namibia Gets New Managing Director 09 | Pan Africa Special Africa Hub To Deliver Multibillion-Dollar Infrastructure Projects / International Freight Forwarders Group Focuses On African Logistics / ACP Leaders Summit Reviews Expiry Of Cotonou Agreement In 2020 / Investec To Manage US$670 Million Infrastructure Fund / AfDB Annual Meeting Sees New Transformation Agenda 13 | Western Africa Regional: Countries Bid As Hubs In China’s Billion-Dollar Silk Road Plan Angola: Weak Maritime Traffic Reduces Revenues At Lobito Port Benin: Terex Delivers Ten Reach Stackers To Cotonou Port Cameroon: Interim EPA - August Takeoff / Doula Port To Get 3rd Crane Cote d’Ivoire: Attracts US$15.4 Billion In Development Funding Ghana: Ghana Deepening Trade Relations With The Swiss Chamber / Ghana Targeting Trade With Russia / Single Window System To Save US$200 Million Annually / Takoradi Port Sees Rising Vessel Numbers / Tema Port Opens Bigger Capacity Bulk Cargo Jetty / GPHA To Relocate Container -

Project for Urban Master Plan of Dakar and Neighboring Area for 2035 Final Report Volume. I

No. Ministry of Urban Renewal, Japan International Cooperation Housing and Living Environment Agency (JICA) Republic of Senegal Project for Urban Master Plan of Dakar and Neighboring Area for 2035 Final Report Volume. I January 2016 Implemented by: RECS International Inc. Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. PACET Corp. CTI Engineering International Co., Ltd. Asia Air Survey Co., Ltd. EI JR 16-002 Ministry of Urban Renewal, Japan International Cooperation Housing and Living Environment Agency (JICA) Republic of Senegal Project for Urban Master Plan of Dakar and Neighboring Area for 2035 Final Report Volume. I January 2016 Implemented by: RECS International Inc. Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. PACET Corp. CTI Engineering International Co., Ltd. Asia Air Survey Co., Ltd. Currency Equivalents (average Interbank rates between May and July, 2015) US$1.00= FCFA 594.04 €1.00= FCFA 659.95 Source: Banque Centrale des Etats de l'Afrique de l'Ouest (BCEAO) Rate Project for Urban Master Plan of Dakar and Neighboring Area for 2035 Final Report: Volume. I Table of Contents Volume. I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Objectives ............................................................................................................................. 1-3 1.3 Study Area ............................................................................................................................ -

Informal Sector in Francophone Africa Public Disclosure Authorized Firm Size, Productivity, and Institutions

AFRICA DEVELOPMENT FORUM Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The Informal Sector in Francophone Africa Public Disclosure Authorized Firm Size, Productivity, and Institutions Nancy Benjamin and Ahmadou Aly Mbaye with Ibrahima Thione Diop, Stephen S. Golub, Dominique Haughton, and Birahim Bouna Niang Public Disclosure Authorized The Informal Sector in Francophone Africa The Informal Sector in Francophone Africa Firm Size, Productivity, and Institutions Nancy Benjamin and Ahmadou Aly Mbaye with Ibrahima Thione Diop, Stephen S. Golub, Dominique Haughton, and Birahim Bouna Niang A copublication of the Agence Française de Développement and the World Bank © 2012 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / Th e World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 15 14 13 12 Th is work is a product of the staff of Th e World Bank with external contributions. Note that Th e World Bank and the Agence Française de Développement do not necessarily own each component of the content included in the work. Th e World Bank and the Agence Française de Développement therefore do not war- rant that the use of the content contained in the work will not infringe on the rights of third parties. Th e risk of claims resulting from such infringement rests solely with you. Th e fi ndings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily refl ect the views of Th e World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, the governments they represent, or the Agence Française de Développement. Th e World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work.