Controlling Pocket Gopher Damage to Conifer Seedlings D.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. EPA, Pesticide Product Label, 0.5% STRYCHNINE MILO for HAND

Jl.l!l€' 23, 1997 Dr. Alan V. Tasker Acting Leader, rata Support Teaill Tec.'mical and Sciemtific Services USDA/AHflS/BBEP Unit ISO ) 4700 River Foad Rivcreale, ND 20737 Dear Dr. Tasker, Subject: 0.5% Str.fclmine Mlo rex Ha.'ld Baiting fucket C,ophers EPA Registratirn No. 56228-19 Your Slil;;nissions of Septemb€r 23, 19%, and June 2, 1997 ~Je nave reviewed ,YOUr sl.ibmi~sicn of Sept€T."'~r 19, 1996:. ThE' cnongp--s in tl"le inert ingredients a'ld t..'1e revised basic and alte..."7late Confidential StatC1"~nts of Forl'1Ula (CSFs) ;;.r8 acceptable. He 1=1<: fort-l;;.rd to receiving the product chemistry data on the nc-w formulation. Your letter of SepteJl'J::>er 23, 19%, imicates thClt some of these studies ~Jere underway at that tire. The proposed revis20 label stibIcJ tted 00 June 2, 1997, is J:-.asically ) acceptC!ble, but the change identified l.-elow must be made. 1. In the "NOI'E TO PHYSICIAN", change "CI\UrION," to "NOrrcp.:" so as not to conflict with the label's required signal Nord "I'i"lNGFR". 8u.1:'mit one r:::q:y of the fin.-J.l printed label before releasing this prcrluct for shipment. :;;~x¥~~ COP~ E William H. JacObs BEST AVA'LAB\.. i\cting Product 1<1a.'l8.ger 14 Insecticide-Rodenticide Branch Reo.istration Division (7505C) :::::, ~.. ..w·-1······ _.. ._-j.. ......w. ··1· "~'~"·Tm--I··· ·1· ............ ·····1· _............. DATE ~ •......••.•....... .........•..••.• ....... ~ ..•....... ..........................................................................................- ....... EPA Form 1320-102-70) OFFICIAL FILE COpy r.. PRECAUTIONARY STATEMENTS 0.5% STRYCHNINE r~1.0 HAZARDS TO HUMANS AND FOR HAND BAITING STORAGE AND DISPOSAL I -, DOMESTIC ANIMALS Do not contaminate water, food, or POCKET GOPHERS feed by storage or disposal. -

Controlling Pocket Gopher Damage to Conifer Seedlings D.S

FOREST PROTECTION EC 1255 • Revised May 2003 $2.50 Controlling Pocket Gopher Damage to Conifer Seedlings D.S. deCalesta, K. Asman, and N. Allen Contents ocket gophers (or just plain Gopher habits and habitat.............. 1 P “gophers”) damage conifer seed- Control program ........................... 2 lings on thousands of Identifying the pest ......................2 acres in Washington, Assessing the need for treatment ...3 Idaho, and Oregon Damage control techniques ...........3 annually. They invade clearcuts and Applying controls .......................... 7 clip (cut off) roots or Figure 1.—Typical Oregon pocket gopher. Christmas tree plantations .............7 girdle (remove bark from) the bases of conifer seedlings and saplings, causing significant economic losses. Forest plantations ........................ 7 This publication will help you design a program to reduce or eliminate Summary .................................... 8 gopher damage to seedlings and saplings in your forest plantation or Christmas tree farm. Sources of supply ......................... 8 First, we describe pocket gophers, their habits, and habitats. Then we For further information .................. 8 discuss procedures for controlling pocket gopher damages—control techniques, their effectiveness and hazard(s) to the environment, and their use under a variety of tree-growing situations. Gopher habits and habitat Three species of pocket gopher can damage conifer seedlings. The two smaller ones, the northern pocket gopher and the Mazama pocket gopher, are 5 to 9 inches long and brown with some white beneath the chin and belly. The northern gopher is found east of the Cascade Mountains in Oregon and Washington and in Idaho; the Mazama lives in Oregon and Washington west of the Cascades. David S. deCalesta, former Exten- The Camas pocket gopher is similar looking, but larger (10 to 12 inches) sion wildlife specialist, and Kim than the two others. -

Benton County Prairie Species Habitat Conservation Plan

BENTON COUNTY PRAIRIE SPECIES HABITAT CONSERVATION PLAN DECEMBER 2010 For more information, please contact: Benton County Natural Areas & Parks Department 360 SW Avery Ave. Corvallis, Oregon 97333-1192 Phone: 541.766.6871 - Fax: 541.766.6891 http://www.co.benton.or.us/parks/hcp This document was prepared for Benton County by staff at the Institute for Applied Ecology: Tom Kaye Carolyn Menke Michelle Michaud Rachel Schwindt Lori Wisehart The Institute for Applied Ecology is a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization whose mission is to conserve native ecosystems through restoration, research, and education. P.O. Box 2855 Corvallis, OR 97339-2855 (541) 753-3099 www.appliedeco.org Suggested Citation: Benton County. 2010. Prairie Species Habitat Conservation Plan. 160 pp plus appendices. www.co.benton.or.us/parks/hcp Front cover photos, top to bottom: Kincaid’s lupine, photo by Tom Kaye Nelson’s checkermallow, photo by Tom Kaye Fender’s blue butterfly, photo by Cheryl Schultz Peacock larkspur, photo by Lori Wisehart Bradshaw’s lomatium, photo by Tom Kaye Taylor’s checkerspot, photo by Dana Ross Willamette daisy, photo by Tom Kaye Benton County Prairie Species HCP Preamble The Benton County Prairie Species Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) was initiated to bring Benton County’s activities on its own lands into compliance with the Federal and State Endangered Species Acts. Federal law requires a non-federal landowner who wishes to conduct activities that may harm (“take”) threatened or endangered wildlife on their land to obtain an incidental take permit from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. State law requires a non-federal public landowner who wishes to conduct activities that may harm threatened or endangered plants to obtain a permit from the Oregon Department of Agriculture. -

Wkhnol2ai96auyxaaa3wmnh8

Copies of this publication may be obtained from the Washington office of the Arctic Institute of North America, 1530 P Street, N. W., Washington 5, D. C. Price 75 cents postpaid. JV s-i — v^rcrt c~a -£*> MUS. MP. 70QL • • • . Li i AUG 11 1960 Vernacular Nameb harvard for North American Mammals North of Mexico %;si. I Jr. /**. /( ^ ^no tfjzjnhesuie/r Museum of Natural History University of Kansas University of Kansas museum of natural history EDITOR: E. RAYMOND HALL Miscellaneous Publication No. 14, pp. 1-16 Published June 19, 1957 Ml/S. ROMP. ZOOU ! SAkY AUG 11 1960 HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRINTED BY FERD VOILAND. JR.. STATE PRINTER TOPEKA. KANSAS 1957 26-8513 VERNACULAR NAMES FOR NORTH AMERICAN MAMMALS NORTH OF MEXICO A committee of The American Society of Mammalogists was formed prior to 1954 to propose vernacular (common) names for American mammals. In 1954, the committee consisted of Donald F. Hoffmeister, Chairman, William H. Burt, W. Robert Eadie, E. Raymond Hall, and Ralph S. Palmer. Correspondence between the chairman (Hoffmeister) and mem- bers of the committee enabled him to prepare, as of January 4, 1954, a list of vernacular names. He circulated this list to members of the committee. On June 16, 1954, the committee met at the Annual Meeting of the Society, (1) decided to propose vernacular names for species, (2) decided not to propose names for subspecies, (3) decided to deal only with the species that occurred north of Mexico, (4) selected many names, and (5) failed to select names for some species. On the basis of the partial list that resulted from the meeting in 1954, the Chairman of the Committee on Nomenclature (Hall), answered inquiries in 1955 and 1956 from several members concern- ing vernacular names. -

Revised Checklist of North American Mammals North of Mexico, 1986 J

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Mammalogy Papers: University of Nebraska State Museum, University of Nebraska State Museum 12-12-1986 Revised Checklist of North American Mammals North of Mexico, 1986 J. Knox Jones Jr. Texas Tech University Dilford C. Carter Texas Tech University Hugh H. Genoways University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Robert S. Hoffmann University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dale W. Rice National Museum of Natural History See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museummammalogy Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Other Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Jones, J. Knox Jr.; Carter, Dilford C.; Genoways, Hugh H.; Hoffmann, Robert S.; Rice, Dale W.; and Jones, Clyde, "Revised Checklist of North American Mammals North of Mexico, 1986" (1986). Mammalogy Papers: University of Nebraska State Museum. 266. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museummammalogy/266 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Museum, University of Nebraska State at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mammalogy Papers: University of Nebraska State Museum by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors J. Knox Jones Jr., Dilford C. Carter, Hugh H. Genoways, Robert S. Hoffmann, Dale W. Rice, and Clyde Jones This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museummammalogy/ 266 Jones, Carter, Genoways, Hoffmann, Rice & Jones, Occasional Papers of the Museum of Texas Tech University (December 12, 1986) number 107. U.S. -

The Use of Aluminum Phosphide in Wildlife Damage Management

Human Health and Ecological Risk Assessment for the Use of Wildlife Damage Management Methods by USDA-APHIS-Wildlife Services Chapter IX The Use of Aluminum Phosphide in Wildlife Damage Management July 2017 Peer Reviewed Final March 2020 THE USE OF ALUMINUM PHOSPHIDE IN WILDLIFE DAMAGE MANAGEMENT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Aluminum phosphide is a fumigant used by USDA-APHIS-Wildlife Services (WS) to control various burrowing rodents and moles. Formulations for burrow treatments are in 3-g tablets or 600-mg pellets containing about 56% active ingredient. WS applicators place the tablets or pellets into the target species’ burrow and seal the burrow entrance with soil. Aluminum phosphide reacts with moisture in burrows to release phosphine gas, which is the toxin in the fumigant. WS applicators used aluminum phosphide to take 19 species of rodents and moles between FY11 and FY15 and treated an annual average of including prairie dogs, ground squirrels, pocket gophers, voles, and moles. WS annually averaged the known take of 54,095 target rodents and an estimated 2,333 vertebrate nontarget species with aluminum phosphide in 9 states. An average of 58,329 burrows was treated with the primary target species being black-tailed and Gunnison’s prairie dogs. APHIS evaluated the human health and ecological risk of aluminum phosphide under the WS use pattern for rodent and mole control. Although phosphine gas is toxic to humans, the risk to human health is low because inhalation exposure is slight for the underground applications. WS applicators wear proper personal protective equipment according to the pesticide label requirements, which reduces their exposure to aluminum phosphide and phosphine gas, and lowers the risk to their health. -

American Beaver American Beaver Pocket Mouse Family

American Beaver • Castor canadensis • 3-4’, tail 11-21”, 35-66 lbs. • Solid dark brown, underneath slightly lighter • Broad, flat, scaly tail • Wide flat head w/small eyes, ears • Extremely large orange incisors • Hind feet webbed • Second nail (someLmes first as well), split for grooming • Second largest rodent aer capybara • Inhabits any fresh water w/ woods nearby • Diet of bark/cambium of willow, birch, aspen, alder • Also herbaceous pond vegetaon American Beaver • Lodges massive piles of mud and sLcks • Create pile first, then chew underwater entrance tunnel and den • Away from bank insLll water, aached to bank in flowing water • Internal lower ledge allows drainage before entering main den • Males may have separate bank burrow • LiUers typically 4 • Begin gnawing before 1 month • Sexually mature at 2 y/o and disperse • Build dams to create ponds • ProtecLon from predators • Maintained for years and generaons Pocket Mouse Family • Great Basin Pocket Mouse* • Perognathus parvus • 6-8”, tail 3.5-4.5”, 7-24g • Pale yellowish brown back w/darker side stripe separang back from white undersides • Bi-colored tail ~2/3 body length • Long hind foot • Arid habitats w/sandy soils • Diet of seeds - cheatgrass, wheat, thistle, wild mustards • Also caterpillars, insects • Tunnel dens deeper in winter • Will plug 3’ at entrance before torpor • Don’t drink water • From food and metabolism • LiUle Pocket mouse • Perognathus longimembris • Dark kangaroo mouse • Microdipodops megacephalus 1 Kangaroo Rats (Pocket Mouse Family) • Ord’s Kangaroo Rat* • Dipodomys -

Facts About Washington's Moles

Moles Though moles are the bane of many lawn owners, they make a significant positive contribution to the health of the landscape. Their extensive tunneling and mound building mixes soil nutrients and improves soil aeration and drainage. Moles also eat many lawn and garden pests, including cranefly larvae and slugs. Moles spend almost their entire lives underground and have Figure 1. Moles have broad front feet, the toes of much in common with pocket gophers—small weak eyes, which terminate in stout claws faced outward for small hips for turning around in tight places, and velvety fur digging. The Pacific or coast mole is shown here. that is reversible to make backing up easy. Moles also have (From Christensen and Larrison, Mammals of Washington: broad front feet, the toes of which terminate in stout claws A Pictorial Introduction.) faced outward for digging (Fig. 1). (The Chehalis Indian word for mole translates into “hands turned backward.”) However, moles are predators of worms and grubs, while gophers are herbivores. (See comparison of their scull shapes in Figure 2.) Three species of moles occur in the Washington. Curiously, moles occur on only a few of the islands in Puget Sound. At a total length of 8 to 9 inches, the slate black Townsend mole (Scapanus townsendii), is the largest mole species in North America. It occurs in meadows, fields, pastures, lawns, and golf courses west of the Cascade mountains. The Pacific mole (Scapanus orarius, Fig. 1), also known as the coast mole, is similar in appearance to the Townsend mole, and ranges from 6 to 7 inches in total length. -

Fleasn and Lice from Pocket Gophers,Thomomys, in Oregon

John O, whitaker,Jr. Department of Life Sciences Indiana StateUniversity Terre Haute, Indiarn 47809 Chris Maset USDI Bureau of Land Managemeot Forestry SciencesLaboratory 3200 Jefferson\Vay Corvallis,Oregon 97331 anq Robert E. Lewis Departmenr of Entomology Iovra State University of Science lo,v/a State University of Science and Technology Ames, Iowa 50011 EctoparasiticMites (ExcludingGhiggers), Fleasn and Lice from Pocket Gophers,Thomomys, in Oregon Abslract Four of the five sDc{iesof pocket eoohers that occur io Oreqon were examined for ecto@rasites: thesetheseincluded:included: (11( 1) CarriasC-amaspocketiocket gopher,Tbo*ony balbiz,o-r*s,(2) Townseod pocket goprer,7.goprer, 7. tountewli.tountewli,tottn:ewli- (1)(1\ Mazama pocketoocket s(gopher,pc:rlter- T.7. mazama, andaod (4(4) ) northernnortiemrern 1rccket1rcckeroocket gopher.eooher.gophe\ T.Z ,albo;des.,alpo;d.es. Although the Botta pocleir gopher,sooher- T. buttae., occursoca'jfs in southwesterosouthwestertr Oreeon.Oregon, oone was includedi in this study. Major ectoparasites wete Ardrolaelabs geamlts and, Geornldoectts oregonat oi T. b*lbbar*s; E.binon,ystas tbonanv, Hdenosdmat*s on'ycbom,ydit, and Geomtdoecas idahoensis on T. toun- endi; Haenoganarzs reidi, Geinydoecn thomomyi; Androlaelips geonzls, aod, Foxella ignota recrla on T. nazama; Geomytloetu thornon tt, Ecbinon";yswsthomorny, Echinonlssa: longicbelae (?), and Foxella ignata rec k onT. tdlPa;.des. lntloduclion Five species of pocket gophers occur in Oregon, all in the gerts Tbomamys; tltey include the Camaspocket gopher,7. bulbiaorut, Townsendpocket gopher,7. ,ou&sendi (listed as 7. u.m.btin*s by Hall 1981), Mazama pocket gopher, T, ,zltzdnw, northetn pocket gopher, T. talpoid,el and Botta pocket gopher, T, bortae. -

Appendix C Wildlife Supplement

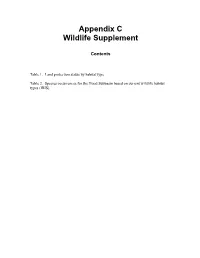

Appendix C Wildlife Supplement Contents Table 1. Land protection status by habitat type Table 2. Species occurrences for the Hood Subbasin based on current wildlife habitat types (IBIS) Table 1. Land Protection Status by habitat type using GIS data layers provided by the Northwest Habitat Institute for the subbasin planning effort. Total Acres subject to discrepancies in input data layers. Metadata link is at www.nwhi.org/ibis/mapping/gisdata/docs/crb/crb_lsstatus_meta.htm. Analysis Area Habitat Protection Status Acres Columbia River Tributaries 63022 Agriculture, pasture and mixed environs 2382 Low 6 Medium 4 None 2372 Montane mixed conifer forest 3653 High 813 Low 2660 Medium 89 None 91 Open water - lakes, rivers, streams 152 High 48 Low 43 Medium 26 None 35 Ponderosa pine forest and woodlands 2 High 2 Urban and mixed environs 1280 Low 126 None 1154 Westside lowlands conifer-hardwood forest 55553 High 31236 Low 17977 Medium 1226 None 5114 Hood River Basin 217492 Agriculture, pasture and mixed environs 33400 Low 152 None 33248 Alpine grassland and shrublands 4469 High 3386 Low 1083 Eastside (interior) grasslands 1538 Low 169 None 1369 Eastside (interior) mixed conifer forest 23194 Low 8252 None 14942 Herbaceous wetlands 197 High 56 Low 141 Montane coniferous wetlands 116 Low 99 None 16 Montane mixed conifer forest 47895 High 14560 Low 33061 None 274 Open water - lakes, rivers, streams 523 High 250 Low 217 None 55 Ponderosa pine forest and woodlands 4739 High 13 Low 1341 None 3385 Subalpine parkland 4394 High 2883 Low 1511 Urban and mixed environs 763 None 763 Westside lowlands conifer-hardwood forest 95388 High 2357 Low 51835 None 41196 Westside oak and dry Douglas-fir forest and woo 876 Low 240 None 636 Subbasin Species Occurrences Generated by IBIS on 10/21/2003 11:09:13 AM. -

Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife

Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Wildlife Control Operator Training Manual Revised March 31, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 1 Page # Introduction 5 Wildlife “Damage” and Wildlife “Nuisance” 5 Part 2 History 8 Definitions 9 Rules and Regulations 11 Part 3 Business Practices 13 Part 4 Methods of Control 15 Relocation of Wildlife 16 Handling of Sick or Injured Wildlife 17 Wildlife That Has Injured a Person 17 Euthanasia 18 Transportation 19 Disposal of Wildlife 20 Migratory Birds 20 Diseases (transmission, symptoms, human health) 20 Part 5 Liabilities 26 Record Keeping and Reporting Requirements 26 Live Animals and Sale of Animals 26 Complaints 27 Cancellation or Non-Renewal of Permit 27 Part 6 Best Management Practices 29 Traps 30 Bodygrip Traps 30 Foothold Traps 30 Box Traps 31 Snares 31 Specialty Traps 32 Trap Sets 33 Bait and Lures 33 Equipment 33 Trap Maintenance and Safety 34 Releasing Nontarget Wildlife 34 2 Resources 36 Part 7 Species: Bats 38 Beaver 47 Coyote 49 Eastern Cottontail 52 Eastern Gray Squirrel 54 Eastern Fox Squirrel 56 Western (Silver) Gray Squirrel 58 Gray Fox 60 Red Fox 62 Mountain Beaver 64 Muskrat 66 Nutria 68 Opossum 70 Porcupine 72 Raccoon 74 Striped Skunk 77 Oregon Species List 79 Part 8 Acknowledgements 83 References and Resources 83 3 Part 1 Introduction Wildlife “Damage” and Wildlife “ Nuisance” 4 Introduction As Oregon becomes more urbanized, wildlife control operators are playing an increasingly important role in wildlife management. The continued development and urbanization of forest and farmlands is increasing the chance for conflicts between humans and wildlife. -

EFED Response To

UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY WASHINGTON, D.C. 20460 OFFICE OF PREVENTION, PESTICIDES AND TOXIC SUBSTANCES September 7, 2004 Memorandum Subject: EFED Response to USDA/APHIS’ “Partner Review Comments: Preliminary Analysis of Rodenticide Bait Use and Potential Risks of Nine Rodenticides to Birds and Nontarget Mammals: A Comparative Approach (June 9, 2004)” To: Laura Parsons, Team Leader Kelly White Reregistration Branch 1 Special Review and Reregistration Division From: William Erickson, Biologist Environmental Risk Branch 2 Environmental Fate and Effects Division Through: Tom Bailey, Branch Chief Environmental Risk Branch 2 Environmental Fate and Effects Division Attached are EFED’s comments on APHIS’ review of the comparative rodenticide risk assessment dated June 9, 2004. We have inserted EFED’s response after each APHIS comment that pertains to the comparative risk assessment (comment 6 relates to BEAD’s benefits assessment). Some of these issues were addressed in EFED’s response to registrants’ comments during the 30-day “errors-only” comment period in 2001 and comments submitted during the 120-day “public-comments” period from January to May of 2003. The present submission also includes a copy of APHIS’ comments from March 31, 2003, and they request that comments 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9 be addressed. EFED addressed those comments in our July 17, 2004 “Response to Public Comments on EFED's Risk Assessment: "Potential Risks of Nine Rodenticides to Birds and Nontarget Mammals: a Comparative Approach", dated December 19, 2002", and we reiterate our response to those comments as well. We have also attached a table of many zinc phosphide use sites, methods of application, application rates and number of applications permitted, although many product labels do not provide that information.