Music Issues Conversations: Native Strategies: N (Enter) S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

California Noise: Tinkering with Hardcore and Heavy Metal in Southern California Steve Waksman

ABSTRACT Tinkering has long figured prominently in the history of the electric guitar. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, two guitarists based in the burgeoning Southern California hard rock scene adapted technological tinkering to their musical endeavors. Edward Van Halen, lead guitarist for Van Halen, became the most celebrated rock guitar virtuoso of the 1980s, but was just as noted amongst guitar aficionados for his tinkering with the electric guitar, designing his own instruments out of the remains of guitars that he had dismembered in his own workshop. Greg Ginn, guitarist for Black Flag, ran his own amateur radio supply shop before forming the band, and named his noted independent record label, SST, after the solid state transistors that he used in his own tinkering. This paper explores the ways in which music-based tinkering played a part in the construction of virtuosity around the figure of Van Halen, and the definition of artistic ‘independence’ for the more confrontational Black Flag. It further posits that tinkering in popular music cuts across musical genres, and joins music to broader cultural currents around technology, such as technological enthusiasm, the do-it-yourself (DIY) ethos, and the use of technology for the purposes of fortifying masculinity. Keywords do-it-yourself, electric guitar, masculinity, popular music, technology, sound California Noise: Tinkering with Hardcore and Heavy Metal in Southern California Steve Waksman Tinkering has long been a part of the history of the electric guitar. Indeed, much of the work of electric guitar design, from refinements in body shape to alterations in electronics, could be loosely classified as tinkering. -

Mahogany Rush, Seattle Center Coliseum

CONCERTS 1) KISS w/ Cheap Trick, Seattle Center Coliseum, 8/12/77, $8.00 2) Aerosmith w/ Mahogany Rush, Seattle Center Coliseum,, 4/19/78, $8.50 3) Angel w/ The Godz, Paramount NW, 5/14/78, $5.00 4) Blue Oyster Cult w/ UFO & British Lions, Hec Edmondson Pavilion, 8/22/78, $8.00 5) Black Sabbath w/ Van Halen, Seattle Center Arena, 9/23/78, $7.50 6) 10CC w/ Reggie Knighton, Paramount NW, 10/22/78, $3.50 7) Rush w/ Pat Travers, Seattle Center Coliseum, 11/7/78, $8.00 8) Queen, Seattle Center Coliseum, 12/12/78, $8.00 9) Heart w/ Head East & Rail, Seattle Center Coliseum, 12/31/78, $10.50 10) Alice Cooper w/ The Babys, Seattle Center Coliseum, 4/3/79, $9.00 11) Jethro Tull w/ UK, Seattle Center Coliseum, 4/10/79, $9.50 12) Supertramp, Seattle Center Coliseum, 4/18/79, $9.00 13) Yes, Seattle Center Coliseum, 5/8/79, $10.50 14) Bad Company w/ Carillo, Seattle Center Coliseum, 5/30/79, $9.00 15) Triumph w/ Ronnie Lee Band (local), Paramount NW, 6/2/79, $6.50 16) New England w/ Bighorn (local), Paramount NW, 6/9/79, $3.00 17) Kansas w/ La Roux, Seattle Center Coliseum, 6/12/79, $9.00 18) Cheap Trick w/ Prism, Hec Edmondson Pavilion, 8/2/79, $8.50 19) The Kinks w/ The Heaters (local), Paramount NW, 8/29/79, $8.50 20) The Cars w/ Nick Gilder, Hec Edmondson Pavilion, 9/21/79, $9.00 21) Judas Priest w/ Point Blank, Seattle Center Coliseum, 10/17/79, Free – KZOK giveaway 22) The Dishrags w/ The Look & The Macs Band (local), Masonic Temple, 11/15/79, $4.00 23) KISS w/ The Rockets, Seattle Center Coliseum, 11/21/79, $10.25 24) Styx w/ The Babys, Seattle -

Dawn Wirth Punk Ephemera Collection LSC.2377

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8tq67pb No online items Finding aid for the Dawn Wirth punk ephemera collection LSC.2377 Finding aid prepared by Kelly Besser, 2020. UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated 2020 May 12. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding aid for the Dawn Wirth LSC.2377 1 punk ephemera collection LSC.2377 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Dawn Wirth punk ephemera collection Creator: Wirth, Dawn, 1960- Identifier/Call Number: LSC.2377 Physical Description: .2 Linear Feet(1 box) Date (inclusive): 1977-2008, bulk 1977-1978 Abstract: Dawn Wirth bought her first camera in 1976, a Canon FTb, with the money she earned from working at the Hanna-Barbera animation studio. She enrolled in a high-school photography class and began taking photos of bands. While still in high school, Wirth captured on film, the beginnings of an underground LA punk scene. She photographed bands such as The Germs, The Screamers, The Bags, The Mumps, The Zeros and The Weirdos in and around The Masque and The Whiskey a Go-Go in Hollywood, California. The day of her high school graduation, Wirth took all of her savings and flew to the United Kingdom where she lived for the next six months and took color photographs of The Clash before they came to America. Dawn Wirth's photographs have been seen in the pages of fanzines such as Flipside, Sniffin' Glue and Gen X and featured in the Vexing: Female Voices from East LA Punk exhibition at Claremont Museum of Art and at DRKRM. -

Boo-Hooray Catalog #8: Music Boo-Hooray Catalog #8

Boo-Hooray Catalog #8: Music Boo-Hooray Catalog #8 Music Boo-Hooray is proud to present our eighth antiquarian catalog, dedicated to music artifacts and ephemera. Included in the catalog is unique artwork by Tomata Du Plenty of The Screamers, several incredible items documenting music fan culture including handmade sleeves for jazz 45s, and rare paste-ups from reggae’s entrance into North America. Readers will also find the handmade press kit for the early Björk band, KUKL, several incredible hip-hop posters, and much more. For over a decade, we have been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections and look forward to inviting you back to our gallery in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Catalog prepared by Evan Neuhausen, Archivist & Rare Book Cataloger and Daylon Orr, Executive Director & Rare Book Specialist; with Beth Rudig, Director of Archives. Photography by Ben Papaleo, Evan, and Daylon. Layout by Evan. Please direct all inquiries to Daylon ([email protected]). Terms: Usual. Not onerous. All items subject to prior sale. Payment may be made via check, credit card, wire transfer or PayPal. Institutions may be billed accordingly. Shipping is additional and will be billed at cost. Returns will be accepted for any reason within a week of receipt. Please provide advance notice of the return. Table of Contents 31. [Patti Smith] Hey Joe (Version) b/w Piss Factory .................. -

America's Hardcore.Indd 278-279 5/20/10 9:28:57 PM Our First Show at an Amherst Youth Center

our first show at an Amherst youth center. Scott Helland’s brother Eric’s band Mace played; they became The Outpatients. Our first Boston show was with DYS, The Mighty COs and The AMERICA’S HARDCORE FU’s. It was very intense for us. We were so intimidated. Future generations will fuck up again THE OUTPATIENTS got started in 1982 by Deep Wound bassist Scott Helland At least we can try and change the one we’re in and his older brother Eric “Vis” Helland, guitarist/vocalist of Mace — a 1980-82 — Deep Wound, “Deep Wound” Metal group that played like Motörhead but dug Black Flag (a rare blend back then). The Outpatients opened for bands like EAST COAST Black Flag, Hüsker Dü and SSD. Flipside called ’em “one of the most brutalizing live bands In 1980, over-with small cities and run-down mill towns across the Northeast from the period.” 1983’s gnarly Basement Tape teemed with bored kids with nothing to do. Punk of any kind earned a cultural demo included credits that read: “Play loud in death sentence in the land of stiff upper-lipped Yanks. That cultural isolation math class.” became the impetus for a few notable local Hardcore scenes. CANCEROUS GROWTH started in 1982 in drummer Charlie Infection’s Burlington, WESTERN MASSACHUSETTS MA bedroom, and quickly spread across New had an active early-80s scene of England. They played on a few comps then 100 or so inspired kids. Western made 1985’s Late For The Grave LP in late 1984 Mass bands — Deep Wound, at Boston’s Radiobeat Studios (with producer The Outpatients, Pajama Slave Steve Barry). -

I Heard That One a Lot, Y'know, When I Was Six, Seven, Eight Years Old. of Course, Every Kid Learns That Pattern and Tries

“OK! Let’s give it to ’em right now!” screamed Jack Ely of the Kingsmen into this microphone at the start of the guitar solo for “Louie Louie.” With its simple song structure, three-chord attack and forbidden teenage appeal, this single song inspired legions of kids in garages across America to pick up guitars and ROCK. “Louie Louie” has become a touchstone in the evolution of rock’n’roll, and with over 1500 recorded cover versions to date, its influence on teenage culture and the future DIY punk underground can’t be underestimated. Ely’s vocals were so rough and unintelligible that some more puritanical listeners interpreted the lyrics as being obscene and complained. This rumor led several radio stations to ban the song and the FBI even launched an investigation. All of this only fueled the popularity of the song, which rocketed up the charts in late 1963, imprinting this grunge ur-message onto successive generations of youth, by way of the Sonics, Stooges, MC5, New York Dolls, Patti Smith, The Clash, Black Flag, and others, all of whom amplified and rebroadcast its powerful sonic meme with their own recorded versions. NEUMANN U-47 MICROPHONE, CA. 1961 “There was this great record, ‘Louie Louie,’ by a band “I was in seventh grade and ritually would watch Hugh from the Pacific Northwest called The Kingsmen. I bought Downs and Barbara Walters with my mother on the Today their album and it was a great influence on me because Show. The Who did sort of an early lip synch video of they were a real professional band, y’know?” ‘I Can See For Miles’ and then they interviewed Townshend – Wayne Kramer, MC5 and Daltrey. -

Bbbwinsaugust Roundtables for Reform and the Evangelical Immigration Table Radio Ads News Clips Aug

BBBwinsAugust Roundtables for Reform and the Evangelical Immigration Table Radio Ads News Clips Aug. 1, 2013 – Sept. 12, 2013 September 12, 2013 TO: Interested Parties FROM: Ali Noorani, National Immigration Forum Action Fund RE: #BBBWinsAugust Impact Report In December of 2012 the National Immigration Forum Action Fund launched Bibles, Badges and Business for Immigration Reform, a network of thousands of local conservative faith, law enforcement and business leaders. Over the course of the August recess, our goal was to provide conservative support for Republican members of Congress by attending Town Halls, convening Roundtables for Reform and engaging local media. The verdict is in: Bibles, Badges and Business won the August recess. Working with a wide range of faith, law enforcement and business allies, over the course of the 5-week recess, the Bibles, Badges and Business for Immigration Reform network: Convened over 40 Roundtables for Reform in key congressional districts. Held 5 statewide telephonic press conferences in critical states. Organized 148 local faith, business and law enforcement leaders to headline the 40 events. Recruited conservative leaders to attend over 65 Town Halls. Generated 371 news stories, 80% of which were local headlines. Earned over 1,000 visits to our dedicated recess website, www.BBBwinsAugust.com. Generated over 1,000 tweets using the dedicated hashtag #BBBwinsAugust Reached over 1,150,000 people via Twitter and Facebook Roundtables for Reform Over the course of the August recess, the Bibles, Badges and Business for Immigration Reform network held 40 Roundtables for Reform in key congressional districts across the Southeast, South, Midwest and West. -

Punk Passage: California and Beyond, 1977-1981 Photographs by Ruby Ray Mining Denver’S Underground Rock Photography: Seldom Seen Scenes in Local Music

Exhibitions: Punk Passage: California and Beyond, 1977-1981 Photographs by Ruby Ray Mining Denver’s Underground Rock Photography: seldom seen scenes in local music. Group show curated by Cinthea Fiss Dates: March 29–May 12, 2012 Public Reception: Thursday, March 29, 6-9 pm. Featuring live music by Fritz Fox of The Mutants. Members’ Preview Reception 5-6 pm. Organized by: Rupert Jenkins & Richard Peterson Place: Colorado Photographic Arts Center, 445 South Saulsbury Street, Lakewood, CO 80226 Hours: TU–SA 12–5.30 pm Events: Music Scene: Presentations and Critiques by Ruby Ray, Richard Peterson, and Cinthea Fiss Date: Saturday March 31, 1-4.30 pm. Place: CPAC Cost: $10/5 presentations only; $25/15 with portfolio critique Punk Passage: California and Beyond, 1977-1981 will be shown at CPAC alongside Mining Denver’s Underground Rock Photography: seldom seen scenes in local music, an exhibition of new Denver music photography curated by Cinthea Fiss. Both exhibitions are presented in collaboration with Search & Destroy, a series of citywide exhibitions, concerts and events in Denver exploring punk’s historical and ongoing relationship to visual art, coordinated around the exhibition Bruce Conner and the Primal Scene of Punk Rock at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver. Partner institutions include Art-Plant, Carmen Wiedenhoeft Gallery, Colorado Photographic Arts Center, Gildar Gallery, Hi-Dive, Lion's Lair, Museum of Contemporary Art Denver and Underground Music Showcase. Mining Denver Rock Photography artists: [email protected], John Schoenwalter, Jason Bye, Brenda LaBier, Spike Photography Exhibition celebrates San Francisco’s explosive Punk Scene of the late 70s In 1977, punk broke through the world psyche like a jackhammer. -

Punk Record Labels and the Struggle for Autonomy 08 047 (01) FM.Qxd 2/4/08 3:31 PM Page Ii

08_047 (01) FM.qxd 2/4/08 3:31 PM Page i Punk Record Labels and the Struggle for Autonomy 08_047 (01) FM.qxd 2/4/08 3:31 PM Page ii Critical Media Studies Series Editor Andrew Calabrese, University of Colorado This series covers a broad range of critical research and theory about media in the modern world. It includes work about the changing structures of the media, focusing particularly on work about the political and economic forces and social relations which shape and are shaped by media institutions, struc- tural changes in policy formation and enforcement, technological transfor- mations in the means of communication, and the relationships of all these to public and private cultures worldwide. Historical research about the media and intellectual histories pertaining to media research and theory are partic- ularly welcome. Emphasizing the role of social and political theory for in- forming and shaping research about communications media, Critical Media Studies addresses the politics of media institutions at national, subnational, and transnational levels. The series is also interested in short, synthetic texts on key thinkers and concepts in critical media studies. Titles in the series Governing European Communications: From Unification to Coordination by Maria Michalis Knowledge Workers in the Information Society edited by Catherine McKercher and Vincent Mosco Punk Record Labels and the Struggle for Autonomy: The Emergence of DIY by Alan O’Connor 08_047 (01) FM.qxd 2/4/08 3:31 PM Page iii Punk Record Labels and the Struggle for Autonomy The Emergence of DIY Alan O’Connor LEXINGTON BOOKS A division of ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. -

His Eyes Looked Like Eggs, with the Yolks Broken Open, With

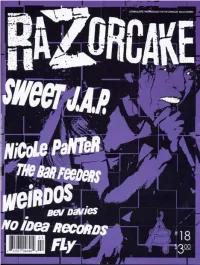

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 #18 www.razorcake.com picked off the road, and sewn back on. If he didn’t move with such is eyes looked like eggs, with the yolks broken open, with authority, it’d’ve been easy to mistake him as broken. bits of blood pulsing through them. Before he even opened His voice caught me off guard. It was soft, resonant. “What’re HHup his grease stained tennis bag, I knew that there was you looking for?” nothing I’d want to buy from him. He unzipped the bag. Inside, “Foot pegs.” I didn’t have to give him the make and model. He there were ten or fifteen carburetors. Obviously freshly stolen, the knew from the connecting bolt I held out. rubber fuel lines cut raggedly and gas leaking out. “Got ‘em. Don’t haggle with me. You got the cash?” I placed “No. I’m just looking for foot pegs.” the money in his hand. “Man, you could really help me out. Sure you don’t want an “That’s what I like. Cash can’t bounce. Follow me.” upgrade? There’s some nice ones in here.” We weaved through dusty corridors, the halls strategically There were some very expensive pieces of metal, highly mined with Doberman shit. To the untrained eye, the place looked polished, winking at me. I could almost hear the death threats their in shambles. No care was taken to preserve the carpet. Inside-facing previous owners’ bellowed into empty parking lots. windows were smashed out. He bent down, opened a drawer with a “No. -

Richard Duardo Interviewed by Karen Mary Davalos on November 5, 8, and 12, 2007

CSRC ORAL HISTORIES SERIES NO. 9, NOVEMBER 2013 RICHARD DUARDO INTERVIEWED BY KAREN MARY DAVALOS ON NOVEMBER 5, 8, AND 12, 2007 Richard Duardo was born in East Los Angeles and is a graduate of UCLA. His serigraphs have been shown internationally and are represented in notable public and private collections, including the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. He is a recipient of an Artist of the Year award from the California Arts Commission. In 1978 he established Hecho en Aztlán, a fine art print studio, followed by Aztlán Multiples, Multiples Fine Art, Future Perfect, Art & Commerce, and his present studio, Modern Multiples, Inc. He has printed the work of more than 300 artists. Duardo lives in Los Angeles. Karen Mary Davalos is chair and professor of Chicana/o studies at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. Her research interests encompass representational practices, including art exhibition and collection; vernacular performance; spirituality; feminist scholarship and epistemologies; and oral history. Among her publications are Yolanda M. López (UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, 2008); “The Mexican Museum of San Francisco: A Brief History with an Interpretive Analysis,” in The Mexican Museum of San Francisco Papers, 1971–2006 (UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, 2010); and Exhibiting Mestizaje: Mexican (American) Museums in the Diaspora (University of New Mexico Press, 2001). This interview was conducted as part of the L.A. Xicano project. Preferred citation: Richard Duardo, interview with Karen Mary Davalos, November 5, 8, and 12, 2007, Los Angeles, California. CSRC Oral Histories Series, no. 9. Los Angeles: UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, 2013. -

Postmodernism and Punk Subculture: Cultures of Authenticity and Deconstruction

The Communication Review, 7:305–327, 2004 Copyright © Taylor & Francis Inc. ISSN: 1071-4421 print DOI: 10.1080/10714420490492238 Postmodernism and Punk Subculture: Cultures of Authenticity and Deconstruction RYAN MOORE Department of Sociology University of Kansas This paper examines punk subcultures as a response to “the condition of postmodernity,” defined here as a crisis of meaning caused by the commodi- fication of everyday life. Punk musicians and subcultures have responded to this crisis in one of two ways. Like other forms of “plank parody” associated with postmodernism, the “culture of deconstruction” expresses nihilism, ironic cynicism, and the purposelessness experienced by young poeple. On the other hand, the “culture of authenticity” seeks to establish a network of underground media as an expression of artistic sincerity and independence from the allegedly corrupting influences of commerce. Although these cultures are in some ways diametrically opposed, they have represented competing tendencies within punk since the 1970s, and I argue that they are both reactions to the same crisis of postmodern society. During the past quarter century, artists, architects, and academics have written and spoken at length about “postmodernism” as manifest in aesthetics, episte- mology, and politics. In philosophy and the social sciences, postmodernism is said to characterize the exhaustion of totalizing metanarratives and substitute localized, self-reflexive, and contingent analyses for the search for objective, uni- versal truth (Best & Kellner, 1991; Clifford & Marcus, 1986; Habermas, 1987; Lyotard, 1984; Rosenau, 1992). In the art world, postmodern style is defined by hybridity and intertextuality, by its license to (re)create using recycled objects and images from the past while locating the residue of previously authored texts within the modern and “original” (Jameson, 1991).