More Than Music: American Punk Rock, 1980-1985

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Endurance News Issue 59

ENDURANCE July 2008 : Issue 059 NEWSThe endurance athlete’s comprehensive knowledge resource since 1992 The Safety of Stevia Bill Misner, Ph.D. & Steve Born Pg 2 Welcome We recently received the following Unsafe or very poorly tested and not Pg 4 From The Saddle Of Steve Born email… worth any risk.” Here is there specific Pg 8 Product Spotlight : Anti-Fatigue Caps analysis: “Small amounts are probably I’ve been a long time user of Hammer safe. High doses fed to rats reduced Pg 10 Pre-Workout/Race Fueling (originally E-CAPS) products. One of sperm production and increased cell Pg 11 Phytoestrogens from Soy Protein the reasons I like them so much is that proliferation in their testicles, which they don’t include artificial ingredients. could cause infertility or other problems. Pg 12 Junior Development Cycling I try not to consume anything that Stevia can be sold in the United States Pg 14 Salt Stains might be harmful to my health. I’m only as a dietary supplement, but several also a subscriber to Nutrition Action Pg 15 Hammer Partners companies are reportedly developing a Health Letter put out by the Center stevia-derived sweetener and plan to Pg 16 Back Pain for Science in the Public Interest, seek approval for the FDA to use it in Pg 17 2008 Events and have considered their publication foods.” reliable for many years. Their latest Pg 18 Getting Faster As You Get Older issue has a guide to food additives. They Pg 20 Muscle Soreness / Weight Gain rated stevia: “Everyone Should Avoid. -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers

Catalog 10 Flyers + Boo-hooray May 2021 22 eldridge boo-hooray.com New york ny Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers Boo-Hooray is proud to present our tenth antiquarian catalog, exploring the ephemeral nature of the flyer. We love marginal scraps of paper that become important artifacts of historical import decades later. In this catalog of flyers, we celebrate phenomenal throwaway pieces of paper in music, art, poetry, film, and activism. Readers will find rare flyers for underground films by Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, and Andy Warhol; incredible early hip-hop flyers designed by Buddy Esquire and others; and punk artifacts of Crass, the Sex Pistols, the Clash, and the underground Austin scene. Also included are scarce protest flyers and examples of mutual aid in the 20th Century, such as a flyer from Angela Davis speaking in Harlem only months after being found not guilty for the kidnapping and murder of a judge, and a remarkably illustrated flyer from a free nursery in the Lower East Side. For over a decade, Boo-Hooray has been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections and look forward to inviting you back to our gallery in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Catalog prepared by Evan Neuhausen, Archivist & Rare Book Cataloger and Daylon Orr, Executive Director & Rare Book Specialist; with Beth Rudig, Director of Archives. Photography by Evan, Beth and Daylon. -

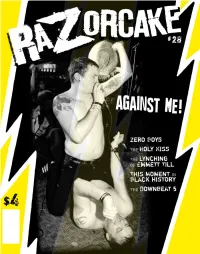

Razorcake Issue #82 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California not-for-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS. -

At Thirty-Three, My Anger Hasn't Subsided. It's Gotten

t thirty-three, my anger hasn’t subsided. It’s gotten And to all this, I don’t have a real answer. I don’t think I’m naïve. I deeper. It’s more like magma keeping me warm instead of lava don’t think I’m expecting too much, but it’s hard not to feel shat upon by AAshooting haphazardly all over the place. It’s managed. You see, the world-at-large every step of the way. There are a couple of things that I’ve been able to channel the balled-fist, I’m hitting-walls-and-breaking- temper my anger. First off, when we were doing our math, I got another knuckles anger into something of a long-burning fuse. Oh, I’m angry, but number: sixty-four. That’s how many folks help out Razorcake in some I’m probably one of the calmest angry people you’re likely to meet. I take way, shape, or form on a regular basis. Damn, that’s awesome. Sixty- all of my “fuck yous” and edit. I take my “you’ve got to be fucking kid- four people, without whom this zine would just be a hair-brained ding me”s and take pictures and write. I seek revenge by working my ass scheme. off. Anger, coupled with belief, is a powerful motivator. The second element is a little harder to explain. Recently, I was in an What do I have to be angry about? I don’t think it’s obvious, but we do adjacent town, South Pasadena. -

Arabs Threaten to Blow up Where

V" A > A O E FORTY WEDNESDAY, JU N E 10/ 1970 ilanrljpatifr Ettaninn il|fralii Most Manchester Stores Open Until 9 O ’clock About Town Average Daily Net Preee Ron On Sunday 14 people becanje Weiss To Pursue mamben of Omter Oon8:re- Q1 For The Week Ended gntlonal CSnirch. They are Mrs. K V ^ June 6, 1070 The Weather NelUe F, Allinaon, 114 Orcep Case Mt. Purchase Moatly fair, mild tosUght with ^I'ectors last night instructed Town 1 5 ,9 0 3 lows 60 to 60. Tomorrow partly Albert J. IMachene HI. 87 Sum- Kobeii; Weiss to meet with owners of Case sunny, humid; ohande o< thun- /} V-»V\ A mar St.; Peter Raymond Mo- ^loimtain and other interested agencies to decide wheth- lUancheoter— A City of Village Charm ■WnrtMwons fate In the day. High quln, 87 Foater St.; Mr. and er the town should apply for'a new federal oiien-spaces about 90. Mra. Kenneth R. Mnness, 262 grant to acquii"e the land. ------ — ------------ --- - VOL. LXXXIX, NO. 214 (TWENTY-FOUR PAGES—^TWO SECinONS) Kue Ridge Dr.; Mrs. Sara K. Last nights’ vote on a motion priority, the town’s share of the MANCHESTER. CONN., THURSDAY, JUNE 11, 1970 Robinson. 181A Downey Dr.; by Director William FitzGerald r„st was estimated at $128,000. h (ClMstfled Adverttslng on Boge St) PRICE TEN CENTS Mrs. Alice Scagel, 170 Charter who strongly supported the ac- The federal government also Oak St.; Mrs. Harriet C. Sliney, qulsition. came after the direc- requires that there be an ” lndl- 851 Summit St.; Mr. -

Razorcake Issue

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 #19 www.razorcake.com ight around the time we were wrapping up this issue, Todd hours on the subject and brought in visual aids: rare and and I went to West Hollywood to see the Swedish band impossible-to-find records that only I and four other people have RRRandy play. We stood around outside the club, waiting for or ancient punk zines that have moved with me through a dozen the show to start. While we were doing this, two young women apartments. Instead, I just mumbled, “It’s pretty important. I do a came up to us and asked if they could interview us for a project. punk magazine with him.” And I pointed my thumb at Todd. They looked to be about high-school age, and I guess it was for a About an hour and a half later, Randy took the stage. They class project, so we said, “Sure, we’ll do it.” launched into “Dirty Tricks,” ripped right through it, and started I don’t think they had any idea what Razorcake is, or that “Addicts of Communication” without a pause for breath. It was Todd and I are two of the founders of it. unreal. They were so tight, so perfectly in time with each other that They interviewed me first and asked me some basic their songs sounded as immaculate as the recordings. On top of questions: who’s your favorite band? How many shows do you go that, thought, they were going nuts. Jumping around, dancing like to a month? That kind of thing. -

Bad Rhetoric: Towards a Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2012 Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Utley, Michael, "Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy" (2012). All Theses. 1465. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1465 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BAD RHETORIC: TOWARDS A PUNK ROCK PEDAGOGY A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Professional Communication by Michael M. Utley August 2012 Accepted by: Dr. Jan Rune Holmevik, Committee Chair Dr. Cynthia Haynes Dr. Scot Barnett TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction ..........................................................................................................................4 Theory ................................................................................................................................32 The Bad Brains: Rhetoric, Rage & Rastafarianism in Early 1980s Hardcore Punk ..........67 Rise Above: Black Flag and the Foundation of Punk Rock’s DIY Ethos .........................93 Conclusion .......................................................................................................................109 -

Big Black Pigpile Mp3, Flac, Wma

Big Black Pigpile mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Pigpile Country: US Released: 1992 Style: Industrial, Noise MP3 version RAR size: 1119 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1815 mb WMA version RAR size: 1934 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 569 Other Formats: MMF VOX ADX MP2 XM MP4 AIFF Tracklist A1 Fists Of Love A2 L Dopa A3 Passing Complexion A4 Dead Billy A5 Cables A6 Bad Penny B1 Pavement Saw B2 Kerosene B3 Steelworker B4 Pigeon Kill B5 Fish Fry B6 Jordan, Minnesota Companies, etc. Record Company – Southern Studios Ltd. Pressed By – MPO Recorded At – Hammersmith Clarendon Notes Recorded at the Hammersmith Clarendon, London, England in Summer 1987. White label in plain white sleeve with New Release letter from Southern Studios, London which has typed tracklist Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Runout Etchings Side A): MPO TG 81 A1 "A Dearth of Jon Spencer or What?" Matrix / Runout (Runout Etchings Side B): MPO TG 81 B1 "Please Increase Playback Volume 2db" Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year TG81 Big Black Pigpile (LP, Album) Touch And Go TG81 US 1992 TG81 Big Black Pigpile (LP, Album, TP) Touch And Go TG81 US 1992 TG81C Big Black Pigpile (Cass) Touch And Go TG81C US 1992 TG81 Big Black Pigpile (LP, Album, RP) Touch And Go TG81 US Unknown SENTO YU-1 Big Black Pigpile (CD, Album) Sento SENTO YU-1 Japan 1992 Related Music albums to Pigpile by Big Black Clash, The - (White Man) In Hammersmith Palais Alexander O'Neal - Live At The Hammersmith Apollo - London Balaam And The Angel - Live At The Clarendon Venom - Fuckin' Hell At Hammersmith The Human League - London Hammersmith Palais 22.5.80 Killing Joke - Live At The Hammersmith Apollo 16.10.2010 Volume 1 Motörhead - No Sleep 'Til Hammersmith Danzig - Die Die My Darling Big Black - Songs About Fucking Venom - Live In Hammersmith Odeon London 08.10.85. -

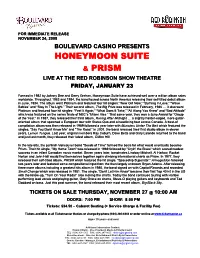

Honeymoon Suite & Prism

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NOVEMBER 24, 2008 BOULEVARD CASINO PRESENTS HONEYMOON SUITE & PRISM LIVE AT THE RED ROBINSON SHOW THEATRE FRIDAY, JANUARY 23 Formed in 1982 by Johnny Dee and Derry Grehan, Honeymoon Suite have achieved well over a million album sales worldwide. Throughout 1983 and 1984, the band toured across North America releasing their self-titled debut album in June, 1984. The album went Platinum and featured four hit singles: “New Girl Now,” “Burning In Love,” “Wave Babies” and “Stay In The Light.” Their second album, The Big Prize was released in February, 1986 … it also went Platinum and featured four hit singles: “Feel It Again,” “What Does It Take,” “All Along You Knew” and “Bad Attitude” which was featured on the series finale of NBC’s “Miami Vice.” That same year, they won a Juno Award for “Group of the Year.” In 1987, they released their third album, Racing After Midnight … a slightly harder-edged, more guitar- oriented album that spawned a European tour with Status Quo and a headlining tour across Canada. A best-of compilation album was then released in 1989 followed a year later with Monsters Under The Bed which featured the singles, “Say You Don’t Know Me” and “The Road.” In 2001, the band released their first studio album in eleven years, Lemon Tongue. Last year, original members Ray Coburn, Dave Betts and Gary Lalonde returned to the band and just last month, they released their latest album, Clifton Hill. In the late 60s, the punkish Vancouver band "Seeds of Time" formed the basis for what would eventually become Prism. -

Compound AABA Form and Style Distinction in Heavy Metal *

Compound AABA Form and Style Distinction in Heavy Metal * Stephen S. Hudson NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: hps://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.21.27.1/mto.21.27.1.hudson.php KEYWORDS: Heavy Metal, Formenlehre, Form Perception, Embodied Cognition, Corpus Study, Musical Meaning, Genre ABSTRACT: This article presents a new framework for analyzing compound AABA form in heavy metal music, inspired by normative theories of form in the Formenlehre tradition. A corpus study shows that a particular riff-based version of compound AABA, with a specific style of buildup intro (Aas 2015) and other characteristic features, is normative in mainstream styles of the metal genre. Within this norm, individual artists have their own strategies (Meyer 1989) for manifesting compound AABA form. These strategies afford stylistic distinctions between bands, so that differences in form can be said to signify aesthetic posing or social positioning—a different kind of signification than the programmatic or semantic communication that has been the focus of most existing music theory research in areas like topic theory or musical semiotics. This article concludes with an exploration of how these different formal strategies embody different qualities of physical movement or feelings of motion, arguing that in making stylistic distinctions and identifying with a particular subgenre or style, we imagine that these distinct ways of moving correlate with (sub)genre rhetoric and the physical stances of imagined communities of fans (Anderson 1983, Hill 2016). Received January 2020 Volume 27, Number 1, March 2021 Copyright © 2021 Society for Music Theory “Your favorite songs all sound the same — and that’s okay . -

Download Internet Service Channel Lineup

INTERNET CHANNEL GUIDE DJ AND INTERRUPTION-FREE CHANNELS Exclusive to SiriusXM Music for Business Customers 02 Top 40 Hits Top 40 Hits 28 Adult Alternative Adult Alternative 66 Smooth Jazz Smooth & Contemporary Jazz 06 ’60s Pop Hits ’60s Pop Hits 30 Eclectic Rock Eclectic Rock 67 Classic Jazz Classic Jazz 07 ’70s Pop Hits Classic ’70s Hits/Oldies 32 Mellow Rock Mellow Rock 68 New Age New Age 08 ’80s Pop Hits Pop Hits of the ’80s 34 ’90s Alternative Grunge and ’90s Alternative Rock 70 Love Songs Favorite Adult Love Songs 09 ’90s Pop Hits ’90s Pop Hits 36 Alt Rock Alt Rock 703 Oldies Party Party Songs from the ’50s & ’60s 10 Pop 2000 Hits Pop 2000 Hits 48 R&B Hits R&B Hits from the ’80s, ’90s & Today 704 ’70s/’80s Pop ’70s & ’80s Super Party Hits 14 Acoustic Rock Acoustic Rock 49 Classic Soul & Motown Classic Soul & Motown 705 ’80s/’90s Pop ’80s & ’90s Party Hits 15 Pop Mix Modern Pop Mix Modern 51 Modern Dance Hits Current Dance Seasonal/Holiday 16 Pop Mix Bright Pop Mix Bright 53 Smooth Electronic Smooth Electronic 709 Seasonal/Holiday Music Channel 25 Rock Hits ’70s & ’80s ’70s & ’80s Classic Rock 56 New Country Today’s New Country 763 Latin Pop Hits Contemporary Latin Pop and Ballads 26 Classic Rock Hits ’60s & ’70s Classic Rock 58 Country Hits ’80s & ’90s ’80s & ’90s Country Hits 789 A Taste of Italy Italian Blend POP HIP-HOP 750 Cinemagic Movie Soundtracks & More 751 Krishna Das Yoga Radio Chant/Sacred/Spiritual Music 03 Venus Pop Music You Can Move to 43 Backspin Classic Hip-Hop XL 782 Holiday Traditions Traditional Holiday Music