Science in the Yukon: Advancing a Vision for Evidence-Based Decision Making by Aynslie E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VIU ASP 2018-19 Proposal-Feb9

Vancouver Island University Aboriginal Service Plan 2018/19 – 2020/21 Submitted by the Office of Aboriginal Education and Engagement February 2018 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Letter from the President ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Acknowledgement of Traditional Territory/Territories .................................................................................................. 6 Situational Context .......................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Institutional Commitment ............................................................................................................................................................ 9 Engagement ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 10 a. Description of Aboriginal Student Engagement .................................................................................................................................... 10 b. Description of External Partner Engagement ....................................................................................................................................... -

Participating Universities and Colleges: Acadia University Algoma University Algonquin College Ambrose University Assiniboine C

Participating universities and colleges: Acadia University Cégep de Thetford Algoma University Cégep de Trois-Rivières Algonquin College Cégep de Victoriaville Ambrose University Cégep du Vieux Montréal Assiniboine Community College Cégep régional de Lanaudière à Joliette Bishop’s University Centennial College Booth University College Centre d'études collégiales de Montmagny Brandon University Champlain College Saint-Lambert Brescia University College Collège Ahuntsic Brock University Collège d’Alma Cambrian College Collège André-Grasset Camosun College Collège Bart Canadian Mennonite University Collège de Bois-de-Boulogne Canadore College Collège Boréal Cape Breton University Collège Ellis Capilano University Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf Carleton University Collège Laflèche Carlton Trail College Collège LaSalle Cégep de l’Abitibi-Témiscamingue Collège de Maisonneuve Cégep de Baie-Comeau Collège Montmorency Cégep de Chicoutimi College of the North Atlantic Cégep de Drummondville Collège O’Sullivan de Montréal Cégep Édouard-Montpetit Collège O’Sullivan de Québec Cégep de la Gaspésie et des Îles College of the Rockies Cégep Gérald-Godin Collège TAV Cégep de Granby Collège Universel Gatineau Cégep Heritage College Collégial du Séminaire de Sherbrooke Cégep de Jonquière Columbia Bible College Cégep de Lévis Concordia University Cégep Marie-Victorin Concordia University of Edmonton Cégep de Matane Conestoga College Cégep de l’Outaouais Confederation College Cégep La Pocatière Crandall University Cégep de Rivière-du-Loup Cumberland College Cégep Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu Dalhousie University Cégep de Saint-Jérôme Dalhousie University Agricultural Campus Cégep de Sainte-Foy Douglas College Cégep de St-Félicien Dumont Technical Institute Cégep de Sept-Îles Durham College Cégep de Shawinigan École nationale d’administration publique Cégep de Sorel-Tracy (ENAP) Cégep St-Hyacinthe École de technologie supérieure (ÉTS) Cégep St-Laurent Fanshawe College of Applied Arts and Cégep St. -

List of Universities and Institutions Represented by Edu World International Surat

List of universities and institutions represented by Edu World International Surat USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, UK, Ireland, Germany, France, Sweden, Netherlands, Austria, Denmark, Finland, Italy, Hungary, Switzerland, Spain, Lithuania, Cyprus, Poland, Czech Republic, Dubai, Malaysia, Mauritius, Malta, Japan and Vietnam. USA Sr. Name No. 1 Arizona State University, Phoenix, Arizona 2 University of California, Riverside, California (Graduate Business Programs and UCR Extension) 3 Virginia Tech Language and Culture Institute, Blacksburg, Virginia (Only UG Pathways) 4 University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 5 Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (UG Gateways, College of Engg- MS only and IEP) 6 University of Delaware, Newark, Delaware (Only UG) 7 George Mason University, Fairfax County, Virginia 8 Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado 9 Duke University, Durham, North Carolina (Master of International Development Policy) 10 Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 11 University of Illinois at Chicago, Illinois 12 Northeastern University, Boston, Massachusetts -D`Amore-McKim School of Business, The College of Professional Studies (CPS) 13 University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida 14 The University of Alabama Tuscaloosa, Alabama 15 Auburn University, Alabama 16 University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah (Only UG) 17 University of Cincinnati, Ohio (Only UG – Pathway and Direct entry) 18 Ohio University, Athens, Ohio (Master of Financial Economics; All UG Programs) 19 University of South Carolina, Columbia, -

University-Indigenous Relations: a Policy Assessment Framework in Four Dimensions in Partial Fulfilment of the Graduate Certificate in Indigenous Nationhood

University of Victoria University-Indigenous Relations: A Policy Assessment Framework in Four Dimensions In partial fulfilment of the Graduate Certificate in Indigenous Nationhood Peter R Elson PhD 8-23-2019 Dedication and Supervision Dedication This paper is dedicated to my older brother Nick Elson (1943-2017) who continues to be interested in my work and George Larivière, age eight, one of the more than 6,000 Indigenous children who did not survive residential school Supervision: Dr Jeff Corntassel, Associate Professor, Faculty of Arts, Indigenous Studies Dr John Burrows, Professor, Faculty of Law, Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Law 1 Table of Contents Dedication and Supervision ....................................................................................................... 1 Summary and Key findings........................................................................................................ 5 Introduction and Background ................................................................................................. 10 Project Purpose ......................................................................................................................... 12 Policy assessment variables .................................................................................................. 13 Methodology .............................................................................................................................. 14 Limitations ................................................................................................................................ -

Yesterday's Gone

Yesterday’s Gone: Exploring possible futures of Canada’s labour market in a post-COVID world February 2021 February YESTERDAY’S GONE 1 Table of Contents 1 Introduction 2 Methodology 3 State of Canada’s Labour Market in 2020 4 Future Trends 5 Conclusion YESTERDAY’S GONE 2 Introduction YESTERDAY’S GONE 3 Introduction We’re living in uncertain and strange times, making it especially Yesterday’s Gone is part of a broader initiative, Employment in 2030: challenging to plan for the next year, never mind the next decade. Action Labs, which seeks to support the design of policies and And yet it is critical in our current economic climate that we under- programs to help workers gain the skills and abilities they need to be stand the breadth of potential changes ahead, to better prepare resilient in the next decade. This project explores how COVID-19 workers for the future of Canada’s labour market. Yesterday’s Gone might impact the trends, foundational skills, and abilities that were outlines 8 megatrends and 34 related meso trends that have the identified in the Forecast of Canadian Occupational Growth (FCOG), potential to impact employment in Canada by 2030. The goal of this launched by the Brookfield Institute for Innovation + Entrepreneurship research is to explore these technological, social, economic, (BII+E) in May 2020. Fundamentally, this project seeks to translate environmental, and political changes, including those influenced by future-looking labour market information, including from the FCOG COVID-19, to inform the design of skill demand programs and policy and this report, into action by co-creating novel, regionally relevant responses. -

The University of Canada North, 1970-1985

LAKEHEAD UNIVERSITY THE UNIVERSITY THAT WASN'T: THE UNIVERSITY OF CANADA NORTH, 1970 - 1985 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF ARTS AND SCIENCE IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY © AMANDA GRAHAM doi: 10.13140/2.1.3043.2320 (issued by ResearchGate, 20 December 2014 WHITEHORSE, YUKON SUBMITTED FEBRUARY 1994 COMPLETED APRIL 1994 DEGREE GRANTED 23 NOVEMBER 1994 PDF version May 2000 Note that the page numbers in the PDF version of this document do not correspond to the submitted version of this thesis. Citations of this document should be to the PDF Edition, 2000. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to acknowledge the assistance of Yukon College, of the Dean of Academic Studies, Mr. Aron Senkpiel, and of Lakehead University Centre for Northern Studies for supporting this project, and of the Northern Sciences Training Program for grants that permitted travel to Inuvik and Yellowknife to examine archival materials and personal files of some of those involved and to conduct interviews. The author would also like to acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Ernest Epp, Lakehead University, Department of History and Dr. Brent Slobodin, Yukon College, for their comments on earlier drafts of this thesis. She would especially like to thank Dr. W. R. Morrison for his guidance and for putting up with her odd ideas and interpretations these last few years. Thanks are also due to Garth Graham (Ottawa), Richard Rohmer (Toronto), Arnold Edinburgh (Toronto), Dick Hill (Inuvik), Nellie Cournoyea (Yellowknife), Ron Veale (Whitehorse), W. Peter Adams (Peterborough), John Hoyt (Whitehorse), Frank Fingland (Whitehorse), Renée Alford (Whitehorse), YTG Department of Education and Julie Cruikshank (Vancouver) among others for sharing their files and/or their recollections of their UCN participation. -

Yukon Mining and Exploration Directory 2021-2022

2021–22 PM41599072 Midnight Sun Drilling Inc. THE BEST OF ** 50 years In Business, serving the North since 1970 ** THE YUKON delivered to your doorstep BINGO TEA CEREMONY ICKY ART Drilling services for the Mining, Municipal, Diamond, & Environmental Industries A favourite Friday pastime A -year-old Japanese tradition Turning scraps into beauty GWITCHIN FIDDLER Ben Charlie is on air HIDDEN NO MORE ® SHOES OFF Black and Asian Yukon history Cabin etiquette you need to know YUKONNORTH of ORDINARY ® ORDINARY YUKONNORTH of DOG CITY OF FOXESPOWERED Feel the pull of bikejoring, skijoring, and canicross The O cial In ight Magazine of PLUS Vol. 15 Issue 1 Spring 2021 TAKING THE PLUNGE www.NorthofOrdinary.com CAN. $6.95 l U.S. $4.95 Jumping into a frigid lake for a cause PM41599072 Display until May 1, 20 21 YUKON North of Ordinary l SPRING 2021 1 The O cial In ight Magazine of plus Vol. 15 Issue 2 Summer 2021 www.NorthofOrdinary.com BERINGIA CAN. $6.95 l U.S. $4.95 What the Blackstone River 1 Ordinary l Summer 2021 reveals about an ancient landscapeYUKON North of PM41599072 21 Display until Aug. 1, 20 ! Subscribe today DRILLING IN N P: 867.633.2626 F: 867.633.2628 Subscribe online: [email protected] www.midnightsundrilling.com northofordinary.com/subscribe C. Mailing Address: #413-108 Elliott Street Whitehorse, Y.T. Y1A 6C4 .midnightsundrilling.com MIDNIGHTwww SU Shop Address: #6 Chadburn Cres. WHITEHORSE Y. T. 2 Yukon MINING & EXPLORATION Directory 2021-22 Yukon MINING & EXPLORATION Directory 2021-22 3 CONTENTS 6 President’s Message 8 Yukon Chamber of Mines Board of Directors 14 Operating in a Pandamic Why we should care about mining in the Yukon 18 Placer Mining Keeping a community going 20 A Day with Angela Kiriak Q&A: An interview with the Alkan Air Ltd. -

Chamber Meeting Day 23

Yukon Legislative Assembly Number 23 3rd Session 34th Legislature HANSARD Thursday, November 14, 2019 — 1:00 p.m. Speaker: The Honourable Nils Clarke YUKON LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY 2019 Fall Sitting SPEAKER — Hon. Nils Clarke, MLA, Riverdale North DEPUTY SPEAKER and CHAIR OF COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE — Don Hutton, MLA, Mayo-Tatchun DEPUTY CHAIR OF COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE — Ted Adel, MLA, Copperbelt North CABINET MINISTERS NAME CONSTITUENCY PORTFOLIO Hon. Sandy Silver Klondike Premier Minister of the Executive Council Office; Finance Hon. Ranj Pillai Porter Creek South Deputy Premier Minister of Energy, Mines and Resources; Economic Development; Minister responsible for the Yukon Development Corporation and the Yukon Energy Corporation Hon. Tracy-Anne McPhee Riverdale South Government House Leader Minister of Education; Justice Hon. John Streicker Mount Lorne-Southern Lakes Minister of Community Services; Minister responsible for the French Language Services Directorate; Yukon Liquor Corporation and the Yukon Lottery Commission Hon. Pauline Frost Vuntut Gwitchin Minister of Health and Social Services; Environment; Minister responsible for the Yukon Housing Corporation Hon. Richard Mostyn Whitehorse West Minister of Highways and Public Works; the Public Service Commission Hon. Jeanie Dendys Mountainview Minister of Tourism and Culture; Minister responsible for the Workers’ Compensation Health and Safety Board; Women’s Directorate GOVERNMENT PRIVATE MEMBERS Yukon Liberal Party Ted Adel Copperbelt North Paolo Gallina Porter Creek Centre Don Hutton -

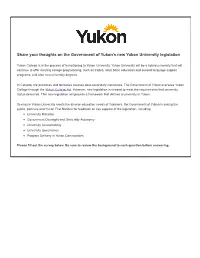

Share Your Thoughts on the Government of Yukon's New Yukon

Share your thoughts on the Government of Yukon’s new Yukon University legislation Yukon College is in the process of transitioning to Yukon University. Yukon University will be a hybrid university that will continue to offer existing college programming, such as trades, adult basic education and second language support programs, and also new university degrees. In Canada, the provinces and territories oversee post-secondary institutions. The Government of Yukon oversees Yukon College through the Yukon College Act. However, new legislation is needed to meet the requirements that university status demands. This new legislation will provide a framework that defines a university in Yukon. To ensure Yukon University meets the diverse education needs of Yukoners, the Government of Yukon is asking the public, partners and Yukon First Nations for feedback on key aspects of the legislation, including: University Mandate Government Oversight and University Autonomy University Accountability University Governance Program Delivery in Yukon Communities Please fill out the survey below. Be sure to review the background to each question before answering. Mandate for Yukon University A piece of legislation normally begins with a description of its intended purpose. This is often referred to as the Objects and Purpose of the legislation. In university legislation, the Objects and Purpose section establishes the university’s mandate. This mandate informs the types of educational programs it will offer. The Objects and Purpose below are being considered -

2019/20 VIEWBOOK YOURSELF HERE HÄN Nëkhwëtrʼënohʼąy Häjit Shò Trʼìnląy

ADMISSIONS / PROGRAMS / ON & OFF CAMPUS / STUDENT LIFE SEE 2019/20 VIEWBOOK YOURSELF HERE HÄN Nëkhwëtrʼënohʼąy häjit shò trʼìnląy. MY STORY | STUDENT PROFILE We are happy to see (all of) you. DENENIZE BASIL KASKA LUTSEL K’E DENE FIRST NATION CITIZEN, RENEWABLE RESOURCES MANAGEMENT STUDENT Dahgátsʼenehtān yéh gutie. It's good to see (all of) you. “I am studying at Yukon College because I want to make a difference in my community. My motivation to keep NORTHERN TUTCHONE studying is to make my grandparents proud. They Dàyę yésóotsʼenindhän, dàkhwätsʼenèʼin yū. believed in me and gave me the encouragement We are happy to see (all of) you. I needed to believe in myself.” SOUTHERN TUTCHONE Denenize Basil is a citizen of the Lutsel k’e Dene First Nation in the Northwest Territories. His future goal is to become a renewable resource officer or conservation ` officer for his First Nation or for the territorial government. Dene has assisted Yukon Dákwänīʼį yū shäw ghànīddhän. College’s Industrial Research Chair in Northern Energy Innovation with Energy Literacy We are happy to see (all of) you. and Demand-Side Management projects, as well as supporting the Northern Climate ExChange with the Chu äyì ätl’et (The Water in Me) project. TAGISH Dahtsʼenehʼįh sùkùsen. It's good to see (all of) you. GWICH'IN Nakhwanyàaʼin geenjit shòh ìidìlii. We are happy to see (all of) you. UPPER TANANA Nohtsʼenehʼįį tsinʼįį choh tsʼeninthän. We are happy to see (all of) you. TLINGIT It’s good to see you. Yakʼê ixhwsatìní. It's good to see you. We would like to thank Yukon First Nations people for welcoming the Yukon College community onto their traditional territories to share educational experiences. -

Join Us at Yukonu

Join us at YukonU Help shape the future of post-secondary in the North, by joining the supportive and collaborative team of staff, faculty and researchers at Yukon University. There has never been a more exciting time to be here. We have just become Yukon University ― the first university north of 60 in Canada. Through this transition, we continue to lead the way in place-based education and northern-focused research and scholarship. We are rooted in the close connections we have to the communities we serve, and to the 14 Yukon First Nations upon whose land we operate. Programs such as our Indigenous Governance Degree and Yukon First Nation core competency were developed in partnership with these nations. Yukon University will move towards the future without losing sight of its past. We offer a place and a pathway for every learner. This means our programs were developed with community members and tailored to their learning needs. And, it means that we excel at offering a wide range of programs, including university preparation, skills and vocational training certificates and diplomas, and degree and post-graduate programs. We connect with diverse learners in many locations through our network of 12 vibrant community campuses. Each campus offers its own unique programming while also being tied into our shared programming. On average, Yukon University serves 1,300 full- and part-time credit students, and more than 4,700 non- credit students each year. The student body includes 150 full-time international students. The place we call home Yukon is home to more caribou than people and more mountains than buildings. -

CIBC Future Heroes Bursary 2020 Program Guidelines

CIBC Future Heroes Bursary 2020 Program Guidelines Background In recognition of the legacy of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, CIBC is investing $500,000 over two years in the education of tomorrow’s healthcare professionals. The CIBC Future Heroes Bursary Program will inspire and support the next generation in their ambition of having a career in healthcare. Number, value and duration of bursaries For the 2020/2021 academic year, one hundred and fifty (150) entrance bursaries will be available to students entering into their first year of a first degree, be it a bachelor or diploma, at eligible Canadian universities and colleges. Please see the list of eligible programs and institutions below. Each scholarship will be valued at $2,500 CAD for a one-year award. Eligibility Eligible applicants must: Be accepted into full-time studies in the first year of a first degree, be it a bachelor or diploma, in the 2020/2021 academic year; Be attending an eligible institution, as identified in the list below; Be enrolled in an eligible program, as identified in the list below; Be a Canadian citizen or permanent resident; Have a minimum cumulative average of 70% (or equivalent) over the last 3 terms of available marks*. Non-academic courses such as career or personal development related courses will not be considered. *Universities Canada’s policy on calculation of average has been developed in consultation with university and college admissions and financial aid officers from across the country. There is enormous diversity amongst the applicants for this scholarship program. The applicants come from different geographical regions and have reached various levels of studies.