World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nd Drrm C Upd Date

NDRRMC UPDATE Sitrep No. 15 re: Effects of Tropical Depression “AGATON” Releasing Officer: USEC EDUARDO D. DEL ROSARIO Executive Director, NDRRMC DATE : 19 January 2014, 6:00 AM Sources: PAGASA, OCDRCs V,VII, IX, X, XI, CARAGA, DPWH, PCG, MIAA, AFP, PRC, DOH and DSWD I. SITUATION OVERVIEW: Tropical Depression "AGATON" has moved southeastward while maintaining its strength. PAGASA Track as of 2 AM, 19 January 2014 Satellite Picture at 4:32 AM., 19 January 2014 Location of Center: 166 km East of Hinatuan, Surigao del Sur (as of 4:00 a.m.) Coordinates: 8.0°N 127.8°E Strength: Maximum sustained winds of 55 kph near the center Movement: Forecast to move South Southwest at 5 kph Monday morninng: 145 km Southeast of Hinatuan, Surigao del Sur Tuesday morninng: Forecast 87 km Southeast of Davao City Positions/Outlook: Wednesday morning: 190 km Southwest of Davao City or at 75 km West of General Santos City Areas Having Public Storm Warning Signal PSWS # Mindanao Signal No. 1 Surigao del Norte (30-60 kph winds may be expected in at Siargao Is. least 36 hours) Surigao del Sur Dinagat Province Agusan del Norte Agusan del Sur Davao Oriental Compostela Valley Estimated rainfall amount is from 5 - 15 mm per hour (moderate - heavy) within the 300 km diameter of the Tropical Depression Tropical Depression "AGATON" will bring moderate to occasionally heavy rains and thunderstorms over Visayas Sea travel is risky over the seaboards of Luzon and Visayas. The public and the disaster risk reduction and management councils concerned are advised to take appropriate actions II. -

Bridges Across Oceans: Initial Impact Assessment of the Philippines Nautical Highway System and Lessons for Southeast Asia

Bridges across Oceans Initial Impact Assessment of the Philippines Nautical Highway System and Lessons for Southeast Asia April 2010 0 2010 Asian Development Bank All rights reserved. Published 2010. Printed in the Philippines ISBN 978-971-561-896-0 Publication Stock No. RPT101731 Cataloging-In-Publication Data Bridges across Oceans: Initial Impact Assessment of the Philippines Nautical Highway System and Lessons for Southeast Asia. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Asian Development Bank, 2010. 1. Transport Infrastructure. 2. Southeast Asia. I. Asian Development Bank. The views expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ADB encourages printing or copying information exclusively for personal and noncommercial use with proper acknowledgment of ADB. Users are restricted from reselling, redistributing, or creating derivative works for commercial purposes without the express, written consent of ADB. Note: In this report, “$” refers to US dollars. 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 -

Directory of Participants 11Th CBMS National Conference

Directory of Participants 11th CBMS National Conference "Transforming Communities through More Responsive National and Local Budgets" 2-4 February 2015 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Academe Dr. Tereso Tullao, Jr. Director-DLSU-AKI Dr. Marideth Bravo De La Salle University-AKI Associate Professor University of the Philippines-SURP Tel No: (632) 920-6854 Fax: (632) 920-1637 Ms. Nelca Leila Villarin E-Mail: [email protected] Social Action Minister for Adult Formation and Advocacy De La Salle Zobel School Mr. Gladstone Cuarteros Tel No: (02) 771-3579 LJPC National Coordinator E-Mail: [email protected] De La Salle Philippines Tel No: 7212000 local 608 Fax: 7248411 E-Mail: [email protected] Batangas Ms. Reanrose Dragon Mr. Warren Joseph Dollente CIO National Programs Coordinator De La Salle- Lipa De La Salle Philippines Tel No: 756-5555 loc 317 Fax: 757-3083 Tel No: 7212000 loc. 611 Fax: 7260946 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Camarines Sur Brother Jose Mari Jimenez President and Sector Leader Mr. Albino Morino De La Salle Philippines DEPED DISTRICT SUPERVISOR DEPED-Caramoan, Camarines Sur E-Mail: [email protected] Dr. Dina Magnaye Assistant Professor University of the Philippines-SURP Cavite Tel No: (632) 920-6854 Fax: (632) 920-1637 E-Mail: [email protected] Page 1 of 78 Directory of Participants 11th CBMS National Conference "Transforming Communities through More Responsive National and Local Budgets" 2-4 February 2015 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Ms. Rosario Pareja Mr. Edward Balinario Faculty De La Salle University-Dasmarinas Tel No: 046-481-1900 Fax: 046-481-1939 E-Mail: [email protected] Mr. -

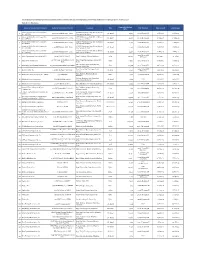

COC Main Grid (As of 18 June 2021)

List of Generation Companies and Generation Facilities with Certificates of Compliance/Provisional Authorities to Operate (as of 18 June 2021) Main Grid - Mindanao Nameplate Rating Name of Generation Company Name of Generation Facility Location Type COC Number Date Issued Date Expiry (kW) Agusan del Norte Electric Cooperative, ANECO Warehouse, Brgy. Bit-os, Butuan 1 2.208 MW Modular DPP - Unit 1 Oil-Based 2,208 18-05-M-00157M 18-May-18 17-May-23 Inc. (ANECO) City, Agusan del Norte Agusan del Norte Electric Cooperative, ANECO Warehouse, Brgy. Bit-os, Butuan 2 2.208 MW Modular DPP - Unit 2 Oil-Based 2,208 18-05-M-00158M 18-May-18 17-May-23 Inc. (ANECO) City, Agusan del Norte Agusan del Norte Electric Cooperative, ANECO Warehouse, Brgy. Bit-os, Butuan 3 2.208 MW Modular DPP - Unit 3 Oil-Based 2,208 18-05-M-00159M 18-May-18 17-May-23 Inc. (ANECO) City, Agusan del Norte Agusan del Norte Electric Cooperative, ANECO Warehouse, Brgy. Bit-os, Butuan 4 2.208 MW Modular DPP - Unit 4 Oil-Based 2,208 18-05-M-00160M 18-May-18 17-May-23 Inc. (ANECO) City, Agusan del Norte Agusan del Norte Electric Cooperative, ANECO Warehouse, Brgy. Bit-os, Butuan 5 2.208 MW Modular DPP - Unit 4 Oil-Based 2,208 18-05-M-00161M 18-May-18 17-May-23 Inc. (ANECO) City, Agusan del Norte 17-08-M-00130M 6 Asian Greenenergy Corporation (AGC) 10.49 MWp DC Solar PP Brgy. Labuagon, Kibawe, Bukidnon Solar 10,490 08-Aug-17 13-Jul-21 (FIT-COC) 8.0 MW Asiga Hydroelectric Power Brgy. -

III IV V Davao Davao Cebu City Cebu City Cebu City Cebu City 0 75

Earthquake Yellow Shaking Alert M 6.5, MINDANAO, PHILIPPINES Origin Time: Fri 2017-02-10 14:03:43 UTC (14:03:43 local) PAGER o o Location: 9.91 N 125.45 E Depth: 15 km Version 7 Created: 6 weeks, 6 days after earthquake Estimated Fatalities Yellow alert for shaking-related fatalities Estimated Economic Losses and economic losses. Some casualties and damage are possible and the impact should be relatively localized. Past yellow alerts 49% have required a local or regional level 37% 37% 27% 21% response. 13% 12% 3% 1% Estimated economic losses are less than 1 100 10,000 1% of GDP of the Philippines. 1 100 10,000 10 1,000 100,000 10 1,000 100,000 Fatalities USD (Millions) Estimated Population Exposed to Earthquake Shaking ESTIMATED POPULATION - -* 24,489k* 15,873k 528k 124k 61k 71k 0 0 EXPOSURE (k = x1000) ESTIMATED MODIFIED MERCALLI INTENSITY PERCEIVED SHAKING Not felt Weak Light Moderate Strong Very Strong Severe Violent Extreme Resistant none none none V. Light Light Moderate Moderate/Heavy Heavy V. Heavy POTENTIAL Structures DAMAGE Vulnerable Structures none none none Light Moderate Moderate/Heavy Heavy V. Heavy V. Heavy *Estimated exposure only includes population within the map area. Population Exposure population per ~1 sq. km from Landscan Structures: Overall, the population in this region resides in structures that are a mix of vulnerable and 123°E 125°E 127°E earthquake resistant construction. Historical Earthquakes (with MMI levels): Date Dist. Mag. Max Shaking (UTC) (km) MMI(#) Deaths CatbaloganCatbalogan IIIIIIIII 1986-08-19 -

Rural Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Project

Completion Report Project Number: 27013 Loan Numbers: 1440/1441 July 2006 Philippines: Rural Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Project CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit – peso (P) At Appraisal At Project Completion 30 April 1996 8 July 2004 P1.00 = $0.0382 $0.0178 $1.00 = P26.18 P56.20 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BME – benefit monitoring and evaluation BWSA – barangay waterworks and sanitation association DILG – Department of the Interior and Local Government DOF – Department of Finance DOH – Department of Health DPWH – Department of Public Works and Highways EA – executing agency EIRR – economic internal rate of return HHE – health and hygiene education IA – implementing agency LGU – local government unit MWT – municipal water sanitation team NGO – nongovernment organization O&M – operation and maintenance PCR – project completion review PMO – project management office PWT – provincial water sanitation team SRA – sector reform agenda WQS – water quality and surveillance WSS – water sanitation and supply GLOSSARY barangay – the smallest political unit into which cities and municipalities in the Philippines are divided. It is the basic unit of the Philippine political system. It consists of less than 1,000 inhabitants residing within the territorial limit of a city or municipality and administered by a set of elective officials, headed by a barangay chairman (punong barangay). NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government and its agencies ends on 31 December. (ii) In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. Vice President C. Lawrence Greenwood, Jr., Operations Group 2 Director General R. Nag, Southeast Asia Department (SERD) Director S. Lateef, Social Sectors Division, SERD Team leader P. van Klaveren, Urban Development Specialist, SERD Team member R. -

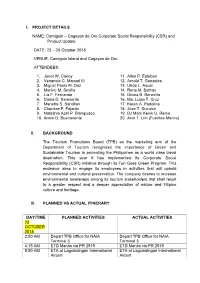

Camiguin CSR Terminal Report

I. PROJECT DETAILS NAME: Camiguin – Cagayan de Oro Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Product Update DATE: 23 – 26 October 2015 VENUE: Camiguin Island and Cagayan de Oro ATTENDEES: 1. Janet W. Canoy 11. Allan P. Esteban 2. Venancio C. Manuel III 12. Arnold T. Gonzales 3. Miguel Paolo M. Daz 13. Uhde L. Asual 4. Marivic M. Sevilla 14. Rene M. Bathan 5. Lia F. Fernando 15. Divina B. Beronilla 6. Diana D. Sarmiento 16. Ma. Luisa T. Cruz 7. Marietta S. Santillan 17. Karen A. Padolina 8. Charisse F. Fajardo 18. Jose T. Ducusin 9. Natashia April P. Blanquisco 19. BJ Mark Kevin U. Remo 10. Annie D. Buenavente 20. Ariel T. Lim (Fuentes Manila) II. BACKGROUND The Tourism Promotions Board (TPB) as the marketing arm of the Department of Tourism recognizes the importance of Green and Sustainable Tourism in promoting the Philippines as a world class travel destination. This year it has implemented its Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiative through its Fun Goes Green Program. This endeavor aims to engage its employees in activities that will uphold environmental and cultural preservation. The company desires to increase environmental awareness among its tourism stakeholders that shall result to a greater respect and a deeper appreciation of nature and Filipino culture and heritage. III. PLANNED VS ACTUAL ITINERARY DAY/TIME PLANNED ACTIVITIES ACTUAL ACTIVITIES 23 OCTOBER 2015 2:00 AM Depart TPB Office for NAIA Depart TPB Office for NAIA Terminal 3 Terminal 3 4:15 AM ETD Manila via PR 2519 ETD Manila via PR 2519 5:50 AM ETA at Laguindingan International ETA at Laguindingan International Airport Airport DAY/TIME PLANNED ACTIVITIES ACTUAL ACTIVITIES 6:00 AM – Proceed to Divine Mercy Shrine, Proceed to Divine Mercy Shrine, 7:00 AM PSB Ulaliman, El Salvador City, PSB Ulaliman, El Salvador City, Misamis Oriental. -

The Project for Study on Improvement of Bridges Through Disaster Mitigating Measures for Large Scale Earthquakes in the Republic of the Philippines

THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS (DPWH) THE PROJECT FOR STUDY ON IMPROVEMENT OF BRIDGES THROUGH DISASTER MITIGATING MEASURES FOR LARGE SCALE EARTHQUAKES IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES FINAL REPORT MAIN TEXT [1/2] DECEMBER 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) CTI ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD CHODAI CO., LTD. NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD. EI JR(先) 13-261(2) Exchange Rate used in the Report is: PHP 1.00 = JPY 2.222 US$ 1.00 = JPY 97.229 = PHP 43.756 (Average Value in August 2013, Central Bank of the Philippines) LOCATION MAP OF STUDY BRIDGES (PACKAGE B : WITHIN METRO MANILA) i LOCATION MAP OF STUDY BRIDGES (PACKAGE C : OUTSIDE METRO MANILA) ii B01 Delpan Bridge B02 Jones Bridge B03 Mc Arthur Bridge B04 Quezon Bridge B05 Ayala Bridge B06 Nagtahan Bridge B07 Pandacan Bridge B08 Lambingan Bridge B09 Makati-Mandaluyong Bridge B10 Guadalupe Bridge Photos of Package B Bridges (1/2) iii B11 C-5 Bridge B12 Bambang Bridge B13-1 Vargas Bridge (1 & 2) B14 Rosario Bridge B15 Marcos Bridge B16 Marikina Bridge B17 San Jose Bridge Photos of Package B Bridges (2/2) iv C01 Badiwan Bridge C02 Buntun Bridge C03 Lucban Bridge C04 Magapit Bridge C05 Sicsican Bridge C06 Bamban Bridge C07 1st Mandaue-Mactan Bridge C08 Marcelo Fernan Bridge C09 Palanit Bridge C10 Jibatang Bridge Photos of Package C Bridges (1/2) v C11 Mawo Bridge C12 Biliran Bridge C13 San Juanico Bridge C14 Lilo-an Bridge C15 Wawa Bridge C16 2nd Magsaysay Bridge Photos of Package C Bridges (2/2) vi vii Perspective View of Lambingan Bridge (1/2) viii Perspective View of Lambingan Bridge (2/2) ix Perspective View of Guadalupe Bridge x Perspective View of Palanit Bridge xi Perspective View of Mawo Bridge (1/2) xii Perspective View of Mawo Bridge (2/2) xiii Perspective View of Wawa Bridge TABLE OF CONTENTS Location Map Photos Perspective View Table of Contents List of Figures & Tables Abbreviations Main Text Appendices MAIN TEXT PART 1 GENERAL CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... -

1 375 a Parcel of Residential Land with Improvements

ITEM AREA INDICATIVE PROPERTY DESCRIPTION LOCATION NO. (sq.m.) PRICE (Php) Along J. Martin St., Martin Subdivision, A parcel of residential land with improvements 1 375 Bantug, Science City of Muñoz, Nueva 3,709,000.00 covered by TCT No. 050-2014002897 1/ 4/ Ecija A residential land covered by TCT No. T-148739 Along Dike Road (Reyes St.), Brgy. 2 1,168 2,953,000.00 1/ Poblacion, Plaridel, Bulacan A parcel of commercial lot with improvements 3 1,041 Brgy. Gulod Labac, Batangas City 16,000,000.00 covered by TCT no. 052-2016001027 1/ One (1) unit Filter Press, Brand/Model/Made: Philippine Ceramics Plant Putsan, Tiwi, 4 N/A 264,000.00 INTECO by Oshina Iron Works Albay Two (2) parcels of residential land covered by Yago Subdivision, Brgy. Murtha, San 5 480 68,000.00 TCT Nos. T-5954 & T-5955 7/ Jose, Occidental Mindoro A parcel of residential land with improvements Brgy. Carmay East, Rosales, 6 270 3,915,000.00 covered by TCT No. T-78231 4/ Pangasinan An agricultural land covered by TCT No. T- 7 6,537 Brgy. Lantap, Bagabag, Nueva Vizcaya 654,000.00 105490 1/ 5/ 15/ A parcel of agricultural land with improvements 8 6,667 Brgy. San Jose, Ormoc City, Leyte 3,995,000.00 covered by TCT No. 39518 2/ 4/ Two (2) parcels of commercial/agricultural land New Villa Cecilia Resort, Brgy. Malao- 9 15,157 with improvements covered by TCT Nos. T- 19,995,000.00 a, Tayabas City, Quezon 370618 & T-370619 2/ 4/ A parcel of residential land with improvement Along Advincula & Carsadang Bago 10 216 1,600,000.00 covered by TCT No. -

REGION 10 Address: Baloy, Cagayan De Oro City Office Number: (088) 855 4501 Email: [email protected] Regional Director: John Robert R

REGION 10 Address: Baloy, Cagayan de Oro City Office Number: (088) 855 4501 Email: [email protected] Regional Director: John Robert R. Hermano Mobile Number: 0966-6213219 Asst. Regional Director: Rafael V Marasigan Mobile Number: 0917-1482007 Provincial Office : BUKIDNON Address : Capitol Site, Malaybalay, Bukidnon Office Number : (088) 813 3823 Email Address : [email protected] Provincial Manager : Leo V. Damole Mobile Number : 0977-7441377 Buying Station : GID Aglayan Location : Warehouse Supervisor : Joyce Sale Mobile Number : 0917-1150193 Service Areas : Malaybalay, Cabanglasan, Sumilao and Impsug-ong Buying Station : GID Valencia Location : Warehouse Supervisor : Rhodnalyn Manlawe Mobile Number : 0935-9700852 Service Areas : Valencia, San Fernando and Quezon Buying Station : GID Kalilangan Location : Warehouse Supervisor : Catherine Torregosa Mobile Number : 0965-1929002 Service Areas : Kalilangan Buying Station : GID Wao Location : Warehouse Supervisor : Catherine Torregosa Mobile Number : 0965-1929002 Service Areas : Wao, and Banisilan, North Cotabato Buying Station : GID Musuan Location : Warehouse Supervisor : John Ver Chua Mobile Number : 0975-1195809 Service Areas : Musuan, Quezon, Valencia, Maramag Buying Station : GID Maramag Location : Warehouse Supervisor : Rodrigo Tobias Mobile Number : 0917-7190363 Service Areas : Pangantucan, Kibawe, Don Carlos, Maramag, Kitaotao, Kibawe, Damulog Provincial Office : CAMIGUIN Address : Govt. Center, Lakas, Mambajao Office Number : (088) 387 0053 Email Address : [email protected] -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BUKIDNON

2010 Census of Population and Housing Bukidnon Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BUKIDNON 1,299,192 BAUNGON 32,868 Balintad 660 Buenavista 1,072 Danatag 2,585 Kalilangan 883 Lacolac 685 Langaon 1,044 Liboran 3,094 Lingating 4,726 Mabuhay 1,628 Mabunga 1,162 Nicdao 1,938 Imbatug (Pob.) 5,231 Pualas 2,065 Salimbalan 2,915 San Vicente 2,143 San Miguel 1,037 DAMULOG 25,538 Aludas 471 Angga-an 1,320 Tangkulan (Jose Rizal) 2,040 Kinapat 550 Kiraon 586 Kitingting 726 Lagandang 1,060 Macapari 1,255 Maican 989 Migcawayan 1,389 New Compostela 1,066 Old Damulog 1,546 Omonay 4,549 Poblacion (New Damulog) 4,349 Pocopoco 880 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Bukidnon Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Sampagar 2,019 San Isidro 743 DANGCAGAN 22,448 Barongcot 2,006 Bugwak 596 Dolorosa 1,015 Kapalaran 1,458 Kianggat 1,527 Lourdes 749 Macarthur 802 Miaray 3,268 Migcuya 1,075 New Visayas 977 Osmeña 1,383 Poblacion 5,782 Sagbayan 1,019 San Vicente 791 DON CARLOS 64,334 Cabadiangan 460 Bocboc 2,668 Buyot 1,038 Calaocalao 2,720 Don Carlos Norte 5,889 Embayao 1,099 Kalubihon 1,207 Kasigkot 1,193 Kawilihan 1,053 Kiara 2,684 Kibatang 2,147 Mahayahay 833 Manlamonay 1,556 Maraymaray 3,593 Mauswagon 1,081 Minsalagan 817 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and Housing Bukidnon Total Population by Province, -

2007 Census of Population

ISSN 0117-1453 2007 Census of Population Report No. 2-26J Volume I Demographic and Housing Characteristics CAMIGUIN Republic of the Philippines National Statistics Office Manila CITATION: National Statistics Office, 2007 Census of Population, Report No. 2 – 26J Demographic and Housing Characteristics, CAMIGUIN, February 2011 ISSN 0117-1453 2007 Census of Population Report No. 2-26J Volume I Demographic and Housing Characteristics CAMIGUIN REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT BENIGNO S. AQUINO III NATIONAL STATISTICAL COORDINATION BOARD Honorable Cayetano W. Paderanga Jr. Chairperson NATIONAL STATISTICS OFFICE Carmelita N. Ericta Administrator Paula Monina G. Collado Deputy Administrator Socorro D. Abejo Director III, Household Statistics Department ISSN 0117-1453 FOREWORD The 2007 Census of Population (POPCEN 2007) Report No. 2 is one of the several publications prepared by the National Statistics Office (NSO) to disseminate the results of the POPCEN 2007. This report provides updated data on the characteristics of the population and their housing units at the national, regional, provincial, and city/municipal levels. Specifically, this report presents the profile of the population with respect to age, sex, marital status, education and school attendance, place of school, overseas workers, usual occupation, and place of work. The report also contains housing data on construction materials of the roof and outer walls, and tenure status of the lot. The results of the POPCEN 2007 are useful data sources of government planners, policy makers, educators, administrators, and community leaders in crafting the country’s social and economic development plans and programs. The NSO acknowledges all the government agencies as well as private entities which have extended their invaluable assistance and support to make this undertaking successful.