Housing Supply

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Model Scheme for the Establishment of Community Councils in Scotland

MODEL SCHEME FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT OF COMMUNITY COUNCILS IN SCOTLAND 1. Introduction Community Councils were first established in Scotland following the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973. Thereafter, the Local Government etc. (Scotland) Act, 1994, which produced the current system of unitary local authorities, made provision for the continuation of community councils. Under the legislation, every local community in Scotland is entitled to petition their local authority to establish a community council in their area. The Model Scheme for Community Councils in Scotland is designed to enable the establishment of community councils across Scotland and to provide a common minimum basic framework governing their creation and operation. 2. Statutory Purposes The statutory purposes of the community councils established under the Model Scheme are set out in Section 51 (2) of the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973, as follows: - ‘’In addition to any other purpose which a community council may pursue, the general purpose of a community council shall be to ascertain, co-ordinate and express to the local authorities for its area, and to public authorities, the views of the community which it represents, in relation to matters for which those authorities are responsible, and to take such action in the interests of that community as appears to it to be expedient and practicable’’ 3. The Role and Responsibilities of Community Councils The general purpose of community councils is to act as a voice for their local area. This will involve them articulating the views and concerns of local people in their area on a wide range of issues of public concern and make representations to their local authority, other public sector bodies and private agencies on matters within their sphere of interest. -

Braehead & Broomridge Heritage Trail

Xpert Xplorer This leaflet is intended to help you explore Stirling Key Heritage Trails and enjoy Stirling as a “Walkable City”. Braehead & Broomridge ROUTE - 2.1 miles / 3.4km (approx. 40 minutes at an average walking pace) Heritage Trail Bus Stop The trails on the map allow you to enjoy and plan circular Heritage Trail routes. The pink core paths are additional routes to enjoy Park at Crawford Hall and walk past the community Start of Xplorer Trail Railway Line the area. garden. Turn left along Millhall Road and safely Railway Station Core Path (city centre) Visit travelinescotland.com to help you plan your cross the railway at the gates. journey to, in and around Stirling. Interpretation Board Battlefield Follow the road until it bends sharply to the left; at that point turn right down the path. Head straight Parking Church on to the miners’ path (NOT the path marked for Fallin / NCN 76) and keep going until you come to the Bannockburn and pass under the bridge 1 2 3 which carries the railway above you. Be careful, the boardwalk under the bridge can flood after heavy Welcome to the rain. At the top of the ramp you should turn to your left Visit walkit.com to help you plan your way around Braehead & Broomridge and walk until you come to some steps. Be careful, Stirling on foot. Heritage Trail at the top of the steps is the main road. Remember to follow the Scottish Outdoor Access Code while exploring the Stirling Heritage Trails. Cross over the road and continue down the steps then follow the path by the burn until you reach a Braehead stretches from the city centre to the junction at the edge of Balquhidderock Wood. -

SCOTTISH RECORD SOCIETY. C J^-'Chceq ~Ojud Capita 6Jxs$ of Yecurrd§> Ylt £93 J

tw mm* w • •• «•* m«! Bin • \: . v ;#, / (SCOTTISH RECORD SOCIETY. C J^-'ChceQ ~oJud Capita 6jXS$ Of Yecurrd§> Ylt £93 J SrwlmCj fcomininanotj THE Commissariot IRecorfc of Stirling, REGISTER OF TESTAMENTS 1 607- 1 800. EDITED BY FRANCIS J. GRANT, W.S., ROTHESAY HERALD AND LYON CLERK. EDINBURGH : PRINTED FOR THE SOCIETY BY JAMES SKINNER & COMPANY. 1904. EDINBURGH : PRINTED BY JAMES SKINNER AND COMPANY. HfoO PREFACE. The Commissariot of Stirling included the following Parishes in Stirling- shire, viz. : —Airth, Bothkennar, Denny, Dunipace, Falkirk, Gargunnock, Kilsyth, Larbert, part of Lecropt, part of Logie, Muiravonside, Polmont, St. Ninian's, Slamannan, and Stirling; in Clackmannanshire, Alloa, Alva, and Dollar in Muckhart in Clackmannan, ; Kinross-shire, j Fifeshire, Carnock, Saline, and Torryburn. During the Commonwealth, Testa- ments of the Parishes of Baldernock, Buchanan, Killearn, New Kilpatrick, and Campsie are also to be found. The Register of Testaments is contained in twelve volumes, comprising the following periods : — I. i v Preface. Honds of Caution, 1648 to 1820. Inventories, 1641 to 181 7. Latter Wills and Testaments, 1645 to 1705. Deeds, 1622 to 1797. Extract Register Deeds, 1659 to 1805. Protests, 1705 to 1744- Petitions, 1700 to 1827. Processes, 1614 to 1823. Processes of Curatorial Inventories, 1786 to 1823. Miscellaneous Papers, 1 Bundle. When a date is given in brackets it is the actual date of confirmation, the other is the date at which the Testament will be found. When a number in brackets precedes the date it is that of the Testament in the volume. C0mmtssariot Jformrit %\\t d ^tirlitt0. REGISTER OF TESTAMENTS, 1607-1800. Abercrombie, Christian, in Carsie. -

British Family Names

cs 25o/ £22, Cornrll IBniwwitg |fta*g BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Hcnrti W~ Sage 1891 A.+.xas.Q7- B^llll^_ DATE DUE ,•-? AUG 1 5 1944 !Hak 1 3 1^46 Dec? '47T Jan 5' 48 ft e Univeral, CS2501 .B23 " v Llb«"y Brit mii!Sm?nS,£& ori8'" and m 3 1924 olin 029 805 771 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924029805771 BRITISH FAMILY NAMES. : BRITISH FAMILY NAMES ftbetr ©riain ano fIDeaning, Lists of Scandinavian, Frisian, Anglo-Saxon, and Norman Names. HENRY BARBER, M.D. (Clerk), "*• AUTHOR OF : ' FURNESS AND CARTMEL NOTES,' THE CISTERCIAN ABBEY OF MAULBRONN,' ( SOME QUEER NAMES,' ' THE SHRINE OF ST. BONIFACE AT FULDA,' 'POPULAR AMUSEMENTS IN GERMANY,' ETC. ' "What's in a name ? —Romeo and yuliet. ' I believe now, there is some secret power and virtue in a name.' Burton's Anatomy ofMelancholy. LONDON ELLIOT STOCK, 62, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. 1894. 4136 CONTENTS. Preface - vii Books Consulted - ix Introduction i British Surnames - 3 nicknames 7 clan or tribal names 8 place-names - ii official names 12 trade names 12 christian names 1 foreign names 1 foundling names 1 Lists of Ancient Patronymics : old norse personal names 1 frisian personal and family names 3 names of persons entered in domesday book as HOLDING LANDS temp. KING ED. CONFR. 37 names of tenants in chief in domesday book 5 names of under-tenants of lands at the time of the domesday survey 56 Norman Names 66 Alphabetical List of British Surnames 78 Appendix 233 PREFACE. -

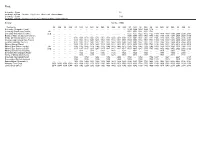

Cowie 54 Via Bridge of Allan

First University - Cowie 54 via Bridge of Allan - Cornton - City Centre - Braehead - Bannockburn University - Cowie 54A via Bridge of Allan - Cornton - City Centre - Whins of Milton - Bannockburn Sunday Ref.No.: 26BM Service No 54 54A 54 54A 54 54A 54 54A 54 54A 54 54A 54 54A 54 54A 54 54A 54 54 54A 54 54A 54 54A 54 University (Alexander Court) .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... 15141544161416441714 .... .... .... .... .... .... .... University (MacRobert Centre) Arr .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... 15211551162116511721 .... .... .... .... .... .... .... University (MacRobert Centre) Dep .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... 152515551625165517251800183019001930200020302100 Bridge of Allan (St Saviours Church) .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... 153016001630170017301805183519051935200520352105 Bridge Of Allan (at Lyon Crescent) .... .... .... .... 1031110111311201123113011331140114311501153116011631170117311806183619061936200620362106 Cornton (opp Cornton Vale Prison) .... .... .... .... 1034110411341204123413041334140414341504153416041634170417341809183919091939200920392109 Cornton (Johnston Avenue) .... .... .... .... 1037110711371207123713071337140714371507153716071637170717371812184219121942201220422112 Stirling (Murray Place) .... .... .... .... 1043111311431213124313131343141314431513154316131643171317431818184819181948201820482118 Stirling (Bus Station Lay By) Arr .... .... .... .... 1045111511451215124513151345141514451515154516151645171517451820185019201950202020502120 -

Threepenny Guide & Directory for Stirling, Bridge of Allan

Threepenny STIRLINC/BRIDCE Of ALLAN, Dunblane, DouNE, Si niniansjcBannockbiirn STIRLING. BRiiCE cf ALLAN sDUNBLANt STIRLING DAVID MILLER * SOW. ^ BAK&H STREE T >0A PATERSON & SONS' LONDON AND PARIS PIASOFOBTE, EARMOMM, ASD MFSIC S A L K S. The Largest Stock of Instruments in Scotland for Sale or Hire. PubUshers of the Celebrated GUINEA EDITION of the SCOTCH SONGS. SECOND-HAND PIANOFOKTES AND HARMONIUMS. PATERSON & SONS Have always on hand a Selection of COTTAGE, SQUARE, AND SEMI-GEAND PIANOFOKTES, SLIGHTLY USED. THE PATENT SIMPLEX PIANETTE, In Rosewood or Walnut, EIGHTEEN GUINEAS. This Wonderful Little Cottage Piano has a good touch, and stands well in Tune. FuU Compass (6i Octv.) HARMONIUMS BY ALEXANDRE, EVANS, and DEBAIN, From 6 to 85 GUINEAS. A Large Selection, both New and Segond-Hand. PATERSON 8c SONS, 27 GEORGE STREET, EDINBURGH; 152 BUCHANAN STREET, GLASGOW; 17 PRINCES STREET, PERTH. National Library Of S^^^^^^^^^^ -k ^^^^^ i^fc^^*^^ TO THE HONOURABLE THE OF THE ^v- Zey /Ma Digitized by the Internet Arciiive in 2010 witii funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/threepennyguided1866dire .. ... insriDExi- - Address, . Stirling, Stirling Castle, Back Walk, . Cemetery, . Ladies' Eock, Hospitals, Drummond's Tract Depot, Post-Office, . Stirling General Directory, Street Directory, Academies and Schools, Places of Worship, Sacramental Fast-Days, . Stirling Young Men's Christain Association, Trades and Professions Directory, Stirling Town Council, &c., Commissioners of Police, Sheriflf Court, Small Debt Court, Commissary Court, Justices of the Peace, Stirling Castle Officials, High School, School of Arts, Faculty of Writers, Parochial Board, Excise Office, Gas-Light Company, ... Water-Works, Athenseum Subscription Eeading-Eooru, Macfarlane Free Library, Newspapers, . -

Gazetteer of Selected Scottish Battlefields

Scotland’s Historic Fields of Conflict Gazetteer: page 1 GAZETTEER OF SELECTED SCOTTISH BATTLEFIELDS LIST OF CONTENTS ABERDEEN II ............................................................................................................. 4 ALFORD ...................................................................................................................... 9 ANCRUM MOOR...................................................................................................... 19 AULDEARN .............................................................................................................. 26 BANNOCKBURN ..................................................................................................... 34 BOTHWELL BRIDGE .............................................................................................. 59 BRUNANBURH ........................................................................................................ 64 DRUMCLOG ............................................................................................................. 66 DUNBAR II................................................................................................................ 71 DUPPLIN MOOR ...................................................................................................... 79 FALKIRK I ................................................................................................................ 87 FALKIRK II .............................................................................................................. -

Sc427 Review of Polling Districts and Polling Places

THIS REPORT RELATES STIRLING COUNCIL TO ITEM ON THE AGENDA STIRLING COUNCIL CHIEF EXECUTIVE 14 SEPTEMBER 2006 NOT EXEMPT REVIEW OF POLLING DISTRICTS AND POLLING PLACES 1 PURPOSE 1.1 To seek approval of the polling districts and polling places detailed in Appendix 1 to the report. 2 SUMMARY 2.1 The Local Government elections in May 2007 will be conducted on the basis of new multi-member wards. On 28 April 2005 the Council considered the Local Government Boundary Commission’s proposals for the division of the Stirling Local Government Area into 7 multi-member wards as part of its statutory review of election boundaries. The Council agreed with the Boundary Commission’s proposals subject to a few minor amendments put forward on the basis of local knowledge. Following a lengthy consultation process the Stirling (Electoral Arrangements) Order 2006 was approved by the Scottish Ministers and came into force on 14 July 2006. 2.2 The Council is required to designate polling districts and polling places for each parliamentary constituency or part thereof situated in the Council’s area and for the wards within each Council area. The new polling districts and polling places need to be confirmed to allow the register of electors to be prepared and published for the combined election next year. 2.3 In formulating the proposals for polling districts and polling places, Officers have tried to provide all electors with reasonable and practicable facilities for voting. The Council is asked to approve the proposed polling districts and polling places, which will form the polling scheme for the Local Government Area. -

I General Area of South Quee

Organisation Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Address Line3 City / town County DUNDAS PARKS GOLFGENERAL CLUB- AREA IN CLUBHOUSE OF AT MAIN RECEPTION SOUTH QUEENSFERRYWest Lothian ON PAVILLION WALL,KING 100M EDWARD FROM PARK 3G PITCH LOCKERBIE Dumfriesshire ROBERTSON CONSTRUCTION-NINEWELLS DRIVE NINEWELLS HOSPITAL*** DUNDEE Angus CCL HOUSE- ON WALLBURNSIDE BETWEEN PLACE AG PETERS & MACKAY BROS GARAGE TROON Ayrshire ON BUS SHELTERBATTERY BESIDE THE ROAD ALBERT HOTEL NORTH QUEENSFERRYFife INVERKEITHIN ADJACENT TO #5959 PEEL PEEL ROAD ROAD . NORTH OF ENT TO TRAIN STATION THORNTONHALL GLASGOW AT MAIN RECEPTION1-3 STATION ROAD STRATHAVEN Lanarkshire INSIDE RED TELEPHONEPERTH ROADBOX GILMERTON CRIEFFPerthshire LADYBANK YOUTHBEECHES CLUB- ON OUTSIDE WALL LADYBANK CUPARFife ATR EQUIPMENTUNNAMED SOLUTIONS ROAD (TAMALA)- IN WORKSHOP OFFICE WHITECAIRNS ABERDEENAberdeenshire OUTSIDE DREGHORNDREGHORN LOAN HALL LOAN Edinburgh METAFLAKE LTD UNITSTATION 2- ON ROAD WALL AT ENTRANCE GATE ANSTRUTHER Fife Premier Store 2, New Road Kennoway Leven Fife REDGATES HOLIDAYKIRKOSWALD PARK- TO LHSROAD OF RECEPTION DOOR MAIDENS GIRVANAyrshire COUNCIL OFFICES-4 NEWTOWN ON EXT WALL STREET BETWEEN TWO ENTRANCE DOORS DUNS Berwickshire AT MAIN RECEPTIONQUEENS OF AYRSHIRE DRIVE ATHLETICS ARENA KILMARNOCK Ayrshire FIFE CONSTABULARY68 PIPELAND ST ANDREWS ROAD POLICE STATION- AT RECEPTION St Andrews Fife W J & W LANG LTD-1 SEEDHILL IN 1ST AID ROOM Paisley Renfrewshire MONTRAVE HALL-58 TO LEVEN RHS OFROAD BUILDING LUNDIN LINKS LEVENFife MIGDALE SMOLTDORNOCH LTD- ON WALL ROAD AT -

Fnh Journal Vol 17

CORRIGENDA FN&H Volume 17 P54—with apologies—the Bold Heading BOOK NOTES/REVIEWS should not precede the article THE NORTHERN EMERALD but follow it above HERITAGE WOOD. the Forth Naturalist Volume 17 Historian 3 Mineral Resource Collecting at the Alva Silver Mines - Brian Jackson 5 The Weather of 1993 - S. J. Harrison 13 Alpine Foxtail (Alopecurus Trin.) in the Ochils - R. W. M. Corner 15 Woodlands for the Community - Alastair Seaman 22 Environmental History - an emergent discipline 23 Forth Area Bird Report 1993 - C. J. Henty 54 The Northern Emerald: an Addition to the Forth Valley Dragonfly Fauna - John T. Knowler and John Mitchell: Hermitage Wood: Symposium 55 Mountain Hares in the Ochil Hills - Alex Tewnion 63 Clackmannan River Corridors Survey - Cathy Tilbrook 67 Book Reviews and Notes (Naturalist) 69 Norway: Author/Reviewers Addresses 70 New Light on Robert Louis Stevenson - Louis Stott 74 R. L. Stevenson and France; Stevenson Essays of Local Interest 75 Bridge of Allan: a Heritage of Music; and its Museum Hall - Gavin Millar and George McVicar 89 Blairlogie: a Short History of Central Scotland's First Conservation village - Alastair Maxwell-Irving 94 Trial of Francis Buchanan 1746 - George Thomson 95 People of the Forth (3) Part 2: David Bruce: Medical Scientist, Soldier, Naturalist - G. F. Follett 103 The Ancient Bridge of Stirling: a New Survey - R. Page 111 Launching Forth: The River - Alloa to Stirling - David Angus 119 Archaeology Notes - Lorna Main and Editor 121 Book Reviews and Notes (Historical) 2 Forth Naturalist and Historian, volume 17 Published by the Forth Naturalist and Historian, a University/Central Regional Council collaboration, and an approved charity. -

Review of Polling Districts and Polling Places

THIS REPORT RELATES STIRLING COUNCIL TO ITEM 8 ON THE AGENDA STIRLING COUNCIL CIVIC SERVICES 8 October 1998 NOT EXEMPT REVIEW OF POLLING DISTRICTS AND POLLING PLACES 1 PURPOSE 1.1 To seek approval of the polling places and polling districts detailed in the polling scheme attached as Appendix 1. 2 SUMMARY 2.1 Stirling Council is required to divide its local government area into polling districts and to designate the polling places for those polling districts. On 5 March 1998 the Council considered the Boundary Commission’s proposals for the division of the Stirling Local Government Area into 22 electoral wards as part of the statutory review of electoral boundaries. The Commission has recently published its final recommendations for the Stirling Council area which are the subject of a separate report on the Agenda. 2.2 The Secretary of State has indicated that the Local Government elections and the elections to the Scottish Parliament will take place on 6 May 1999, with the local elections conducted on the basis of the new electoral wards. As a result, new polling districts and polling places for the new wards require to be confirmed to allow the 1999 draft register of electors to be prepared and subsequently published. 2.3 On 25 June 1998, the Council considered a report outlining the preliminary work undertaken by Officers in looking at the location, suitability and availability of premises within the new electoral wards which could serve as polling places. The proposed polling places were approved in principle to assist the process of drafting polling districts. -

2018 – 2021 Business Plan

2018 – 2021 Business Plan Contents 1. Reference data 2. Executive Summary 3. About Stirling Community Enterprise 3.1 Our vision 3.2 Our mission 3.3 Our services 3.4 Service standards 3.5 Employer partners 3.6 Our learners 3.7 Commercial contracts 4. Our people 4.1 Our staff 4.2 Governance 5. The impact of welfare reform 5.1 Welfare Reform Bill (2012) 5.2 Supporting those with disabilities and learning needs 5.3 Accommodation 5.4 Universal Credit 6. Marketing and communications 7. Financial overview 7.1 Our 3 year cash flow 7.2 Company reserve policy 7.3 Financial risk 7.4 Business support review 8. Kildean Employability and Enterprise Hub 9. Measuring Impact 10. Raploch Urban Regeneration Company 2006 – 2015 11. History of Stirling Community Enterprise 12. References 13. Appendices Appendix 1: SCE Provision 2017-18 Appendix 2: SCE Outcomes and Objectives Appendix 3: SCE Residency Breakdown 2016 Appendix 4: Raploch Site Map SCE 2018 - 2021 2 1. Reference data Stirling Community Enterprise 146 Drip Road Stirling FK8 1RW 01786 472885 SQA Centre Number: 3010430 Website : www.stirlingcommunityenterprise.co.uk Facebook : www.facebook.com/StirlingCommunityEnterprise Stirling Community Enterprise Limited (SCE) Registered address as above Company Registration No 301672 Raploch Urban Regeneration Company Ltd (RURC) Registered address as above Scottish Charity No SC037372 Company Registration No SC303300 SCE 2018 - 2021 3 2. Executive summary Tackling inequalities that exist in terms of poverty, education, employment, income, health and wellbeing in Stirling is not only pivotal to improving the opportunities and life experiences that people can have but it is critical to improving Stirling’s future economic success.