¬タワI'm Gonna Get Me a Loosie¬タン Understanding Single Cigarette

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tobacco Roads: an Exploration of the Meaning and Situatedness of Smoking

Tobacco Roads: An Exploration of the Meaning and Situatedness of Smoking among Homeless Adult Males in Winnipeg by Michelle Bobowski A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of University of Manitoba In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF NURSING Faculty of Nursing University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba Copyright © 2012 by Michelle Bobowski i ABSTRACT Homeless individuals are some of the most marginalized Canadians and most likely to use tobacco daily. The transient nature of homeless smokers contributes to marginalization within health care as well as tobacco control strategies. The purpose of this study was to describe acquisition and smoking behaviors of homeless individuals as a first step in developing essential research evidence to inform tobacco control strategies relevant to this vulnerable population. This ethnographic study investigated the everyday reality of 15 male homeless individuals living in the Salvation Army Shelter in Winnipeg. Tobacco use was explored against their environmental and social contexts, homeless smokers used an informal street-based economy for acquisition, and smoking behaviors were high risk for infectious diseases with sharing and smoking discarded cigarettes. Tobacco control strategies that consider homeless individuals have the potential to reduce morbidity and mortality along with diminishing inequitable health burdens with this population. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am heartily thankful to my supervisor, Dr. Annette Schultz, whose encouragement, guidance and support has taken me from my first tobacco class in 2007 to this final level of writing. Dr. Schultz you have enabled me to develop an understanding of Tobacco Control and have fostered my passion for knowing more and more about the topic of smoking. -

Open Veldheer Dissertation-Final-3

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School School of Behavioral Sciences and Education WHAT HAVE LOW INCOME SMOKERS LEARNED FROM A LIFETIME OF EXPOSURE TO PUBLIC HEALTH PEDAGOGY? A NARRATIVE INQURY A Dissertation in Lifelong Learning and Adult Education by Susan J. Veldheer © 2018 Susan J. Veldheer Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education May 2018 ii The dissertation of Susan J. Veldheer was reviewed and approved* by the following: Robin Redmon Wright Associate Professor of Lifelong Learning and Adult Education Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Karin Sprow Forté Assistant Professor of Teaching, Lifelong Learning, and Adult Education Jonathan Foulds Professor of Public Health Sciences and Psychiatry Eugene J. Lengerich Professor of Public Health Sciences Elizabeth J. Tisdell Professor-In-Charge, Lifelong Learning and Adult Education *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. iii ABSTRACT Though the prevalence of smoking continues to decline overall each year, in segments of the population, such as those with low income or low education levels, the prevalence of smoking is almost double that of the general population. The slower rates of decline in these groups are possibly due to the unexpected ways that public health messages are received, understood, and assimilated into the lives of individuals in these groups. This qualitative study used narrative inquiry methods to understand what 15 low income smokers with less than a bachelor’s degree have learned from a lifetime of exposure to public health pedagogical messages and how this learning may have contributed to their smoking behavior. This study was informed by critical theory which assumes that power and influence within society are unequally distributed, and experiential learning and public pedagogy which consider what people learn from public sites. -

Crime, Class, and Labour in David Simon's Baltimore

"From here to the rest of the world": Crime, class, and labour in David Simon's Baltimore. Sheamus Sweeney B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) This thesis is submitted to Dublin City University for the award of Ph.D in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. August 2013 School of Communications Supervisors: Prof. Helena Sheehan and Dr. Pat Brereton I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Ph.D is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: ___________________________________ (Candidate) ID No.: _55139426____ Date: _______________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Literature review and methodology 17 Chapter One: Stand around and watch: David Simon and the 42 "cop shop" narrative. Chapter Two: "Let the roughness show": From death on the 64 streets to a half-life on screen. Chapter Three: "Don't give the viewer the satisfaction": 86 Investigating the social order in Homicide. Chapter Four: Wasteland of the free: Images of labour in the 122 alternative economy. Chapter Five: The Wire: Introducing the other America. 157 Chapter Six: Baltimore Utopia? The limits of reform in the 186 war on labour and the war on drugs. Chapter Seven: There is no alternative: Unencumbered capitalism 216 and the war on drugs. -

Page 1 DBA BORO STREET ZIPCODE NEW YORK INSTITUTE

NYCFoodInspectionInBrooklynAndManhattan Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results DBA BORO STREET ZIPCODE ISLAND CZ CAFE Brooklyn FRANKLIN AVENUE 11238 LA TRANQUILITE Brooklyn AVENUE L 11236 RESTAURANT INC BAKER'S PIZZA + Manhattan 10 AVENUE 10019 ESPRESSO CHECKERS Manhattan WEST 125 STREET 10027 CHEFS CLUB BY FOOD & Manhattan LAFAYETTE STREET 10012 WINE GREAT N.Y. Manhattan BOWERY 10013 NOODLETOWN TACO BELL Brooklyn FLATBUSH AVENUE 11226 TACO BELL Brooklyn FLATBUSH AVENUE 11226 CROWN FRIED CHICKEN Brooklyn LIVONIA AVENUE 11212 THE BAGEL FACTORY Brooklyn 5 AVENUE 11215 GHOROA RESTAURANT Brooklyn MCDONALD AVENUE 11218 SAXON & PAROLE Manhattan BOWERY 10012 GEE WHIZ Manhattan GREENWICH STREET 10007 STICKY'S FINGER JOINT Manhattan EAST 23 STREET 10010 810 DELI & CAFE Manhattan 7 AVENUE 10019 810 DELI & CAFE Manhattan 7 AVENUE 10019 SEABREEZE FOOD Brooklyn RALPH AVENUE 11236 BENJAMIN STEAK HOUSE Manhattan EAST 41 STREET 10017 Page 1 of 546 09/29/2021 NYCFoodInspectionInBrooklynAndManhattan Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results CUISINE DESCRIPTION INSPECTION DATE Caribbean 06/16/2017 Caribbean 03/07/2019 Pizza 11/02/2018 Hamburgers 08/29/2019 French 12/05/2018 Chinese 08/01/2018 Tex-Mex 01/16/2018 Tex-Mex 01/16/2018 Chicken 08/31/2018 Bagels/Pretzels 05/30/2017 Bangladeshi 08/07/2019 American 05/17/2018 American 07/30/2019 American 08/30/2021 American 08/10/2021 American 08/10/2021 Caribbean 03/22/2018 Steakhouse 08/02/2019 Page 2 of 546 09/29/2021 NYCFoodInspectionInBrooklynAndManhattan Based on DOHMH New -

Newsletter Easter 2003

Newsletter from the Section for the Arts of Eurythmy, Speech and Music Easter 2003 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface . 2 Obituaries Stage Forum May Vera Leroi (Gunna Gusevski) . 42 Lea van der Pals (Cara Groot, Christoph Graf, Merce Cunningham – the path of a dancer today Werner Barfod, Ruth Dubach) . 42 (Werner Barfod) . 2 Margarete Proskauer (Werner Barfod) . 45 Impressions of the performance Coming and Going In Erinnerung an Hildegard Bittorf – Kliegel (Helmut Kohlhepp) . 3 (Catherine Meier, Charlotte de Roguin) . 45 Articles Announcements Study on the first steps in eurythmy Events organised by the Section . 46 by Lory (Maier-)Smits, (Elisabeth Day) . 4 Eurythmy . 46 The Impulses of Movement of the Human Ether-Body Speech . 51 – Part III (Rosemaria Bock) . 6 Music . 53 Eurythmy as an Instrument for Crossing the Threshold Puppetry . 53 consciously – to the fourth, fifth and sixth dimensions (Dr Sabine Sebastian) . 9 Biographical report The Speech-Sound in Eurythmy and the Forms of the Soul-Body (Thomas Göbel) . 12 From Marie Savitch’s life (Eva Lunde) . 53 Can we open up afresh the sources of the art of eurythmy? A work report (Anne Hildebrandt-Dekker) . 15 Book Reviews/Publications Hygienic Eurythmy for Spiritual Practitioners (Minke de Vos) . 19 Die Bedeutung der Holzplastik Rudolf Steiners für Voices of the Angels (Michael Schlesinger) . 25 die anthroposophische Kunst unter besonderer From I O A to I A O in the Foundation Stone Verse Berücksichtigung von Musik und Eurythmie (Helga Steiner) . 25 by Sophia-Imme Atwood . 54 “What is Eurythmy?”—Finding a Healing Basis for New publications from Verlag am Goetheanum . 54 this Communal Search (Mark Ebersole) . -

Cancer Council Victoria Submission Consultation on the Proposal For

Cancer Council Victoria Cancer Council Victoria Submission Consultation on the proposal for standardised tobacco packaging and the implementation of Article 5.3 of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control June 2015 Declaration: We do not have any direct or indirect links to, or receive funding from, the tobacco industry. Contact: Kylie Lindorff, Manager, Tobacco Control Policy, Cancer Council Victoria. Email: [email protected] Cancer Council Victoria Contents Summary ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 About Cancer Council Victoria .................................................................................................................. 7 1.2 Plain packaging as part of a comprehensive tobacco control regime in Australia .................................... 7 2. Research post implementation of plain packaging in Australia ................................................................. 8 2.1 Industry responses to plain packaging ...................................................................................................... 8 2.2 Industry arguments about unintended consequences .............................................................................. 8 (a) Product retrieval time and retailer impact ......................................................................................... -

Vacation Delectation

GRANT’ ® S JAMES GRANT EDITOR Vacation delectation To the readers of Grant’s: The attached anthology of recent you, but also for your friends—and co-workers,Grant’s pieces clients, is notclassmates, only for shipmates, brothers-in-law and maids-of-honor, too. Please pass it along, with our compliments, to any and all prospective members of the greater Grant’s family. We resume publication with the issue dated Sept. 3. Sincerely yours, James Grant Subscribe today and save! Fax or mail the form below, go to www.grantspub.com/subscribe or call 212-809-7994. Yes, I want to subscribe. Enclosed is my payment (check or credit card). Offer good until Dec. 15, 2010 I understand I may cancel at any time for a prorated refund on the remainder of my subscription. On the Web: Offer code: SB2010 o 1 year (24 issues) $910 U.S. /$950 Foreign This offer: $850 U.S./$890 Foreign—a $60 discount Questions? Call 212-809-7994. Fax your order: 212-809-8492 o 2 years (48 issues) 50 ISSUES for $1,660 U.S./$1,700 Foreign. We will add two free issues (an additional $140 value) onto the end of Name _________________________________________________________________ your 2-year subscription. Best value yet! Company _____________________________________________________________ o Check enclosed* Address _______________________________________________________________ *Payment to be made in U.S. funds drawn upon a U.S. bank made out to Grant’s. _________________________________________________________________________ # __________________________________________________________________ -

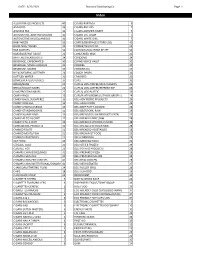

3/22/2021 Standard Distributing Co. Page 1 ALLIGATOR ICE

DATE: 3/22/2021 Standard Distributing Co. Page 1 Index ALLIGATOR ICE PRODUCTS 40 CIGARS-PARTAGA 6 ANTACIDS 33 CIGARS-PHILLIES 7 ARIZONA TEA 31 CIGARS-SWISHER SWEET 7 AUTOMOTIVE-ADDITIVES/FLUIDS 35 CIGARS-U.S. CIGAR 7 AUTOMOTIVE-MISCELLANEOUS 36 CIGARS-WHITE OWL 7 BABY NEEDS 33 COFFEE/BEVERAGE (STORE USE) 40 BAND AIDS/ SWABS 33 COFFEE/TEA/COCOA 23 BAR SUPPLIES 34 COLD/SINUS/ALLERGY RELIEF 33 BARBEQUE/HOT SAUCE 22 CONDENSED MILK 23 BATTERIES/FLASHLIGHTS 34 CONDOMS 34 BEVERAGE, CARBONATED 30 CONVENIENCE VALET 32 BEVERAGE, MISCELLANEOUS 31 COOKIES 20 BEVERAGE, MIXERS 30 COOKING OIL 23 BLEACH/FABRIC SOFTENER 24 COUGH DROPS 33 BOTTLED WATER 31 CRACKERS 20 BOWLS/PLATES/UTENSILS 37 CUPS 36 BREAD/BUNS 27 CUPS & LIDS-COFFEE/JAVA CLASSICS 36 BREAD/DOUGH MIXES 22 CUPS & LIDS-COFFEE/REFRESH EXP 36 CAKE/FROSTING MIXES 22 CUPS & LIDS-PLASTIC 36 CANDY-BAGS 15 CUPS/PLATES/BOWLS/UTENSILS(RESELL) 24 CANDY-BAGS, SUGARFREE 16 DELI-ADV PIERRE PRODUCTS 29 CANDY-KING SIZE 12 DELI-ASIAN FOOD 29 CANDY-MISCELLANEOUS 13 DELI-BEEF PATTY,COOKED 28 CANDY-STANDARD BARS 11 DELI-BEEF/PORK, RAW 28 CANDY-XLARGE BARS 13 DELI-BREAD/DOUGH PRODUCTS FRZN 29 CANDY-45 TO 10 CENT 12 DELI-BREADED BEEF,RAW 28 CANDY-5 TO 2 CENT 12 DELI-BREADED CHICKEN,COOKED 28 CANNABIDIOL PRODUCTS 32 DELI-BREADED CHICKEN,RAW 28 CANNED FRUITS 21 DELI-BREADED VEGETABLES 28 CANNED MEATS/FISH 21 DELI-BREAKFAST FOOD 29 CANNED VEGETABLES 21 DELI-CORNDOGS 29 CAT FOOD 23 DELI-MEXICAN FOOD 29 CEREALS, COLD 23 DELI-OTHER FROZEN 29 CEREALS, HOT 23 DELI-POTATO PRODUCTS 28 CHAMPS CHKN BOXES/BAGS 41 DELI-PREPARED -

Tobacco 21 White Paper Mar.2019.Pdf

Tobacco 21 in Michigan: New Evidence and Policy Considerations March 2019 Contributors: Holly Jarmana, David Mendeza, Rafael Mezaa, Alex Libera,b, Karalyn Kiesslinga, Charley Willisona, Sarah Wanga, Megan Robertsc, Elizabeth Kleinc, Tammy Changa, Leia Gua, Cliff Douglasa,b Affiliations: aUniversity of Michigan; bAmerican Cancer Society; cOhio State University DOI: 2027.42/148298 Overview In this white paper, the team of authors seeks to accomplish three primary goals. In Sections 1 and 2 they communicate what a Tobacco 21 policy is and illustrate the environment in which a Tobacco 21 policy is trying to be introduced in the state of Michigan. In Sections 3 through 5 they share the findings of the UM IHPI Tobacco 21 Policy Sprint, which introduces fresh research and ideas into the Tobacco 21 policy debate to help educate and inform all of those who want to learn more about the potential consequences and requirements of Tobacco 21 policy in Michigan. For those interested in learning more about the methods behind the 3 research projects, please see Appendix 1 in this paper. Finally, in Section 6 the authors provide recommendations to the audience of readers in the state of Michigan and beyond regarding how they believe an effective, equitable, and just Tobacco 21 policy should be constructed, implemented and enforced. Acknowledgements This report would not exist without the generosity of our interviewees, who contributed their time and shared their experiences freely. We thank each of them for their contributions. Our thanks also go to the staff at the Institute of Healthcare Policy and Innovation and our colleagues at the University of Michigan School of Public Health for their support and encouragement during the project, and to our colleagues around the state who volunteered to read and comment on the report prior to publication. -

2018 Tobacco Grantees

CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE TOBACCO GRANT PROGRAM 2018-2019 I I I - ALAMEDA COUNTY - APPLICANT AWARD SUMMARY OF AWARD ' Alameda Police Department $357,695 The Alameda Police Department's Crime Prevention Unit will increase student awareness of the risks of tobacco products and eliminate flavored tobacco sales by hiring a new school resource officer to conduct school presentations and install vaping sensors in schools. ' Piedmont Police Department $391,599 The Piedmont Police Department will hire a school resource officer to conduct student and parent education classes on the harms of tobacco use and conduct tobacco enforcement. - San Leandro Police Department $91,424 The San Leandro Police Department will develop and post no smoking signage. The police department will also develop a webpage about tobacco control laws, conduct outreach sessions with schools that do not currently have a school resource officer, and provide presentations to Youth Action Committee meetings. ' BUTTE COUNTY ' APPLICANT AWARD SUMMARY OF AWARD Butte County Office of Education $1,638,459 The Butte County Office of Education will reduce access to tobacco products to youth, reduce youth exposure to secondhand smoke and nicotine, increase awareness of tobacco and emerging products, enhance overall safety and security of schools by enforcing tobacco-related retail license laws through annual operations, install smoke and vapor detectors in high schools, provide training to sworn personnel and school staff on tobacco-related issues, conduct tobacco-related forums to parents and community, and provide nicotine experimentation and addiction identification and intervention to community. Chico Unified School District $1,225,179 The Chico Unified School District will provide monitoring, enforcement, education and outreach to reduce and eventually eliminate the use of tobacco by school-aged youth by increasing campus supervision, installing smoke and vapor detectors, and providing monthly trainings on tobacco- related issues to sworn personnel, staff, students and parents. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 116 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 116 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 166 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 27, 2020 No. 39 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was into law, calling it ‘‘a new kind of na- RECOGNIZING THE 176TH ANNIVER- called to order by the Speaker pro tem- tional park.’’ Today, nearly 40 years SARY OF DOMINICAN REPUBLIC pore (Mr. CUELLAR). later, our Nation touts 55 National Her- INDEPENDENCE f itage Areas across the country. The SPEAKER pro tempore. The I am proud of the 12 National Herit- Chair recognizes the gentleman from DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO age Areas in Pennsylvania, more than New York (Mr. ESPAILLAT) for 5 min- TEMPORE any other State in the Nation. Na- utes. The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- tional Heritage Areas in Pennsylvania Mr. ESPAILLAT. Mr. Speaker, today fore the House the following commu- span 57 of our 67 counties, and these is February 27, and we celebrate the nication from the Speaker: areas are truly an economic develop- 176th anniversary of independence of ment powerhouse. the Dominican Republic, which gained WASHINGTON, DC, In 2014, tourists spent an estimated $2 February 27, 2020. billion worth of goods and services dur- its independence in 1844 from the Re- I hereby appoint the Honorable HENRY ing their travels to Pennsylvania’s Na- public of Haiti. CUELLAR to act as Speaker pro tempore on Led by Juan Pablo Duarte, Sanchez, tional Heritage Areas. That is $2 bil- this day. -

June 28, 2021 the Council of the District of Columbia John A. Wilson

June 28, 2021 The Council of the District of Columbia John A. Wilson Building 1350 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, DC 20004 Dear Chairman Mendelson and Councilmembers: The undersigned civil rights, civil liberties, and free market organizations write to express our deep concerns regarding the Flavored Tobacco Product Prohibition Amendment Act of 2021 (B24-0020). Currently under consideration by the City Council, it would prohibit the sale and distribution of all “flavored” tobacco products. While no doubt well-intentioned, this proposal raises serious concerns that many of the undersigned groups have previously expressed toward similar proposals.1 Policies that amount to a prohibition for adults have serious implications for racial equity, in terms of both criminal and health justice. Such a ban will trigger law enforcement action, which disproportionately impacts people of color. Furthermore, by prioritizing criminalization over harm reduction and conflating all tobacco products—regardless of their relative risks and potential benefits—it may exacerbate longstanding health disparities in the District. For these reasons, we urge you to reject the current proposal and seek an alternative means of protecting the health and welfare of District residents of all ages. Eric Garner, who was killed by New York Police officers using excessive force, was initially approached for alleged selling “loosie” cigarettes. In 2020, a Rancho Cordova police officer was caught on video brutally beating 14-year-old Elijah Tufono for allegedly purchasing a Swisher cigar underage.2 Just this month, four teenagers were beaten, tasered, and arrested for vaping in Ocean City, Maryland, after violating a ban on smoking or vaping on the boardwalk.3 While we understand the Council’s well-intentioned desire to discourage youth initiation of nicotine use and promote public health, this prohibitionist approach will serve as another point of law enforcement contact in over-policed communities.