Iain Buckland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Producer Guide

Food & Drink Producer Guide 2021/22 Edition scotlandsfooddrinkcounty.com Food & Drink Producer Guide 2021/22 Welcome to East Lothian, Scotland’s Food and Drink County East Lothian has a wonderfully diverse food and drink offering and this guide will help you discover the very best produce from the region. It has never been easier to shop local and support our producers. Whether you are a business wanting to connect to our members or a visitor wishing to find out more about the county’s variety of food and drink produce, this guide will help you to make easy contact. We have listed our members’ social channels and websites to make it easy for you to connect with producers from the region. There is also a map that pinpoints all of our producers and while you can’t visit them all in person, we hope that the map inspires you to think about where your food and drink comes from. And whether you are a local or a visitor, we would encourage you to explore. We hope you enjoy learning about East Lothian’s wonderful producers and that the directory encourages you to #SupportLocal Eat. Drink. Shop. East Lothian. Our Members Drinks - Alcoholic Spices, Preserves & Dry Belhaven Brewery 4 Black & Gold 23 Buck & Birch 5 Edinburgh Preserves 26 Fidra Gin 6 Hoods Scottish Honey 27 Glenkinchie Distillery 7 Mungoswells Malt & Milling 28 Hurly Burly Brewery 8 PureMalt Products 29 Leith Liqueur Company 9 RealFoodSource 30 NB Distillery 10 Spice Pots 31 Thistly Cross Cider 11 The Spice Witch 32 Winton Brewery 12 Chilled Drinks - Non Alcoholic Anderson’s Quality Butcher 33 Brodie Melrose Drysdale & Co 13 Belhaven Lobster 34 Brose Oats 14 Belhaven Smokehouse 35 By Julia 15 The Brand Family Larder 36 Purely Scottish 16 Clark Brothers 37 Steampunk Coffee 17 East Lothian Deli Box 38 Findlay’s of Portobello 39 Bakery & Sweet James Dickson & Son 40 Bostock Bakery 18 JK Thomson 41 The Chocolate Stag 19 John Gilmour Butchers 42 Chocolate Tree 20 WM Logan 43 Dunbar Community Bakery 21 Yester Farm Dairies 44 The Premium Bakery 22 Frozen Member’s Map 24 Di Rollo Ice Cream 45 S. -

Your Wedding Day at Buchan Braes Hotel

Your Wedding Day at Buchan Braes Hotel On behalf of all the staff we would like to congratulate you on your upcoming wedding. Set in the former RAF camp, in the village of Boddam, the building has been totally transformed throughout into a contemporary stylish hotel featuring décor and furnishings. The Ballroom has direct access to the landscaped garden which overlooks Stirling Hill, making Buchan Braes Hotel the ideal venue for a romantic wedding. Our Wedding Team is at your disposal to offer advice on every aspect of your day. A wedding is unique and a special occasion for everyone involved. We take pride in individually tailoring all your wedding arrangements to fulfill your dreams. From the ceremony to the wedding reception, our professional staff take great pride and satisfaction in helping you make your wedding day very special. Buchan Braes has 44 Executive Bedrooms and 3 Suites. Each hotel room has been decorated with luxury and comfort in mind and includes all the modern facilities and luxury expected of a 4 star hotel. Your guests can be accommodated at specially reduced rates, should they wish to stay overnight. Our Wedding Team will be delighted to discuss the preferential rates applicable to your wedding in more detail. In order to appreciate what Buchan Braes Hotel has to offer, we would like to invite you to visit the hotel and experience firsthand the four star facilities. We would be delighted to make an appointment at a time suitable to yourself to show you around and discuss your requirements in more detail. -

Scottish Menus

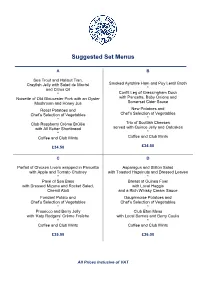

Suggested Set Menus A B Sea Trout and Halibut Tian, Crayfish Jelly with Salad de Maché Smoked Ayrshire Ham and Puy Lentil Broth and Citrus Oil * * Confit Leg of Gressingham Duck Noisette of Old Gloucester Pork with an Oyster with Pancetta, Baby Onions and Somerset Cider Sauce Mushroom and Honey Jus Roast Potatoes and New Potatoes and Chef’s Selection of Vegetables Chef’s Selection of Vegetables * * Club Raspberry Crème Brûlée Trio of Scottish Cheeses with All Butter Shortbread served with Quince Jelly and Oatcakes * * Coffee and Club Mints Coffee and Club Mints £34.50 £34.50 C D Parfait of Chicken Livers wrapped in Pancetta Asparagus and Stilton Salad with Apple and Tomato Chutney with Toasted Hazelnuts and Dressed Leaves * * Pavé of Sea Bass Breast of Guinea Fowl with Dressed Mizuna and Rocket Salad, with Local Haggis Chervil Aïoli and a Rich Whisky Cream Sauce Fondant Potato and Dauphinoise Potatoes and Chef’s Selection of Vegetables Chef’s Selection of Vegetables * * Prosecco and Berry Jelly Club Eton Mess with ‘Katy Rodgers’ Crème Fraîche with Local Berries and Berry Coulis * * Coffee and Club Mints Coffee and Club Mints £35.00 £36.00 All Prices Inclusive of VAT Suggested Set Menus E F Confit of Duck, Guinea Fowl and Apricot Rosettes of Loch Fyne Salmon, Terrine, Pea Shoot and Frissée Salad Lilliput Capers, Lemon and Olive Dressing * * Escalope of Seared Veal, Portobello Mushroom Tournedos of Border Beef Fillet, and Sherry Cream with Garden Herbs Fricasée of Woodland Mushrooms and Arran Mustard Château Potatoes and Chef’s Selection -

Dinner Menus

Accommodation, Conferences and Events DINNER MENUS If you are looking for a unique guest experience, our team of professional caterers will strive to deliver the exceptional service you expect from the University of St Andrews. Our staff take pride in delivery of each individual event, be it a continental breakfast for twelve people, a wedding breakfast for fifty to a gala dinner for three hundred. With a passion for flair, the catering and events team will work with you to create the menu you desire to complement any theme or goals, or you can choose from our range of specifically designed options to suit your event. Whatever your choice, the calibre of food and service provided will be delivered with a personal investment from each of our team members to ensure that your event is special and memorable. DINNER MENU Dinner selector STARTER Sweet potato and coconut soup Curry oil drizzle (v) £5.00 Marinated vine-ripened tomato and baby mozzarella salad Basil infused oil (v) £6.00 Pickled pear salad Walnut soil and blue cheese (v) £5.75 Classic chicken liver pâté Fruit chutney and smoked Scottish oatcake £5.95 Gin-cured salmon Soda bread, lime and tonic aioli £6.50 Haggis, neeps and tatties Malt whisky sauce £5.50 Pan seared scallop Pea purée and pancetta oil £6.75 All prices are inclusive of VAT Food allergens and intolerances: If you have a food allergen or intolerance, prior to placing your order, please highlight this with us and we can guide you through our menu. University of St Andrews t: +44 (0) 1334 463000 e: [email protected] w: ace.st-andrews.ac.uk The University of St Andrews is a charity registered in Scotland, No: SC013532. -

A Dinner at the Governor's Palace, 10 September 1770

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1998 A Dinner at the Governor's Palace, 10 September 1770 Mollie C. Malone College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Malone, Mollie C., "A Dinner at the Governor's Palace, 10 September 1770" (1998). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626149. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-0rxz-9w15 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A DINNER AT THE GOVERNOR'S PALACE, 10 SEPTEMBER 1770 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of American Studies The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Mollie C. Malone 1998 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 'JYIQMajl C ^STIclU ilx^ Mollie Malone Approved, December 1998 P* Ofifr* * Barbara (farson Grey/Gundakerirevn Patricia Gibbs Colonial Williamsburg Foundation TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv ABSTRACT V INTRODUCTION 2 HISTORIOGRAPHY 5 A DINNER AT THE GOVERNOR’S PALACE, 10 SEPTEMBER 1770 17 CONCLUSION 45 APPENDIX 47 BIBLIOGRAPHY 73 i i i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to thank Professor Barbara Carson, under whose guidance this paper was completed, for her "no-nonsense" style and supportive advising throughout the project. -

Hot & Cold Fork Buffets

HOT & COLD FORK BUFFETS Option 1- Cold fork buffet- £14.00 + vat - 2 cold platters, 3 salads and 1 sweet Option 2 - £15.50 + VAT - 1 Main Course (+ 1 Vegetarian Option), 1 Sweet Option 3 - £22.00 + VAT - 2 Main Course (+ 1 Vegetarian Option), 2 Salads, 2 Sweets Add a cold platter and 2 salads to your menu for £5.25 + VAT per person. Makes a perfect starter. COLD PLATTERS Cold meat cuts (Ayrshire ham, Cajun spiced chicken fillet and pastrami Platter of smoked Scottish seafood) Scottish cheese platter with chutney and Arran oaties (Supplement £4 pp & vat) Duo of Scottish salmon platter (poached and teriyaki glazed) Moroccan spice roasted Mediterranean vegetables platter MAINS Collops of chicken with Stornoway black pudding, Arran mustard mash potatoes and seasonal greens Baked seafood pie topped with parmesan mash, served with steamed buttered greens Tuscan style lamb casserole with tomato, borlotti beans and rosemary with pan fried polenta Roast courgette and aubergine lasagne with roasted Cajun spiced sweet potato wedges Jamaican jerk spice rubbed pork loin with spiced cous cous and honey and lime roasted carrots. Chicken, peppers and chorizo casserole in smoked paprika cream with roasted Mediterranean vegetables and braised rice Balsamic glazed salmon fillets with steamed greens and baby potatoes with rosemary, olive oil and sea salt Haggis, neeps and tatties, served with a whisky sauce Braised mini beef olives with sausage stuffing in sage and onions gravy with creamed potatoes All prices exclusive of VAT. Menus may be subject to change -

We're A' Jock Tamson's Bairns

Some hae meat and canna eat, BIG DISHES SIDES Selkirk and some wad eat that want it, Frying Scotsman burger £12.95 Poke o' ChipS £3.45 Buffalo Farm beef burger, haggis fritter, onion rings. whisky cream sauce & but we hae meat and we can eat, chunky chips Grace and sae the Lord be thankit. Onion Girders & Irn Bru Mayo £2.95 But 'n' Ben Burger £12.45 Buffalo Farm beef burger, Isle of Mull cheddar, lettuce & tomato & chunky chips Roasted Roots £2.95 Moving Munros (v)(vg) £12.95 Hoose Salad £3.45 Wee Plates Mooless vegan burger, vegan haggis fritter, tomato chutney, pickles, vegan cheese, vegan bun & chunky chips Mashed Tatties £2.95 Soup of the day (v) £4.45 Oor Famous Steak Pie £13.95 Served piping hot with fresh baked sourdough bread & butter Steak braised long and slow, encased in hand rolled golden pastry served with Champit Tatties £2.95 roasted roots & chunky chips or mash Cullen skink £8.95 Baked Beans £2.95 Traditional North East smoked haddock & tattie soup, served in its own bread Clan Mac £11.95 bowl Macaroni & three cheese sauce with Isle of Mull, Arron smoked cheddar & Fresh Baked Sourdough Bread & Butter £2.95 Parmesan served with garlic sourdough bread Haggis Tower £4.95 £13.95 FREEDOM FRIES £6.95 Haggis, neeps and tatties with a whisky sauce Piper's Fish Supper Haggis crumbs, whisky sauce, fried crispy onions & crispy bacon bits Battered Peterhead haddock with chunky chips, chippy sauce & pickled onion Trio of Scottishness £5.95 £4.95 Haggis, Stornoway black pudding & white pudding, breaded baws, served with Sausage & Mash -

Appetizers- -Sandwiches- -Soup & Salad- -Stone Classics

The Stone of Accord 4951 North Reserve Street, Missoula, MT 59808 406-830-3210 -SANDWICHES- -STONE CLASSICS- www.seankellys.com/Stone Of Accord served with a pickle and choice of fresh-cut fries, add a dinner salad or cup of soup for 2.95 pub chips, rice pilaf, vegetable, champs, soup, din- ner salad HORSERADISH GORGONZOLA STEAK 8 oz sirloin steak, horseradish gorgonzola butter, REUBEN served with champs, vegetable, and soda bread 23.95 -SOUP & SALAD- house slow-cooked corned beef, sauerkraut, Swiss -APPETIZERS- cheese, and 1000 island dressing on thick grilled light FISH & CHIPS dressings : balsamic soy, sesame ginger, garlic CRISPY IRISH EGGROLLS rye 11.95 beer-battered cod, pub chips or fries gorgonzola, honey red vinaigrette, asiago garlic, 1000 coleslaw, tartar sauce, lemon 7.95/12.95 shredded corned beef, cabbage and Asian spices, island, or ranch add: chicken 3– /shrimp 5 EMERALD ISLE CHICKEN SANDWICH served with spicy peanut sauce 9.95 grilled chicken, Dubliner cheese, ham, whiskey onions SHEPHERD’S PIE SOUP o’DAY CHEESY CHIPS and Sriracha aioli served deluxe on a Kaiser roll 121.95 ground chuck, mushrooms and vegetables in a rich ask your server: 3.95 cup/ 5.95 bowl gravy, baked with champs and melted cheddar 12.95 the Stone’s pub chips tossed with asiago and CAJUN CHICKEN SANDWICH gorgonzola cheeses and baked, then topped with DINNER SALAD 2.95 blackened chicken and Sriracha aioli served MOM’S MEATLOAF garlic gorgonzola dressing and scallions 7.95/12.95 deluxe on a Kaiser roll 10.95 house perfected meatloaf topped with sautéed -

Dam Event Room

Dam Event Room As you may or may not know, we are actually boat people. We have been running the passenger boat in De Pere since 2015 and the one in Appleton since 2018. We love bringing people to the water!! That is the reason we started the Bistro, to be able to do just that, all year around. Our years of planning events on the boats bring a bit of a different way to run events. We do whatever it takes to help you have the best event that you can possibly have and know that you will enjoy it just that much more because you held it by the river! Part of that enjoyment comes from us making sure that the process is as stress-free as possible. As if you were simply holding the gathering in your favorite aunt’s house, (or on her boat) - very comfortable and easy. That being said, have no fear, because your aunt is a wonderful chef! Our kitchen crew will create the culinary experience that you envision, or even better. We are blessed to have them on our team! Now, we bet you would like some information! Hopefully, we answer most of your questions below. Dam Room Accommodations: · Newly renovated gathering place in the historic Atlas Mill along the Fox River in Appleton, WI · Wonderful views of the rushing water just below the dam, bringing you the sights and sounds of the river like no other place in the area! · Local, custom built, reclaimed maple and steel dining tables · Padded, sturdy non-folding wood chairs · Depending on group size, access to hand crafted pottery · Capacity for 2021 is 55. -

Food Truck Event & Wedding Offering Brunch

Food Truck Event & Wedding Offering Scottish Street Food Brunch £6 per person Crumpets, Scottish rarebit topping Whiskey & vanilla porridge, heather honey Granola, organic full fat yoghurt, compote £8 per person Scrambled eggs, smoked salmon, sourdough toast Tattie scone, poached egg, lemon hollandaise Edinburgh Food Social, 11 Blackfriars Street, EH11NB 0131 5562350 [email protected] Breakfast sourdough sarnie, streaky bacon, mushroom, fried egg Brunch tuck box – Streaky bacon or Portobello roll, breakfast muffin, seasonal fruit, orange juice - £9.50 per guest All Day Food Priced individually per guest, choice of two options for event Soup & Sourdough - Scotch Broth, Partan bree, or onion & cider - £5 Croque McMonsieur, seasonal slaw - £7 Lobster & crab brioche, fries - £14 Sourdough toasties – Cheddar & chorizo, goats cheese & walnut pesto, roast squash & butterbean hummus £7 Braised organic blade of beef Stovies - £10 Seasonal vegetable & herb stew - £9 Scotch Pie, neeps & tatties, gravy - £13 Edinburgh Food Social, 11 Blackfriars Street, EH11NB 0131 5562350 [email protected] Sausages, rumbledethumps, mustard and cider sauce - £11 Beef and pork chilli, nachos, sour cream, guacamole £12 Seasonal vegetable curry, pilau rice, naan - £10 Arbroath smoky, sea shore veg, herb risotto - £14 Scottish mussels & fries – white wine & cream or chilli, ginger & coconut - £10 Supper snack box – Scotch egg, slaw, seasonal salad, cranachan and shortbread - £10 Sweet Things £5 per guest, choice of two options for event Raspberry Cranachan Scones, jam & clotted cream Lemon posset, vanilla shortbread Walnut & almond brownies Edinburgh Food Social, 11 Blackfriars Street, EH11NB 0131 5562350 [email protected] . -

What's up the Rosedale Newsletter

What’sWhat’s UpUp The Rosedale Newsletter January 2019 special New Year’s message from planning some entertaining events dur- chair Stephen Leibbrandt to all the ing its tenure till the AGM in July. We are A Rosedale Service Centre mem- always open to suggestions so, do pass bers in particular and readers in general: on any good ideas you might have. I can be contacted at 082 95 95 911. Food for thought: we’re nearly a fifth of the way through the 21st century and, Besides the social activities we will as we enter 2019, I’d like to wish you as be involved in we’re remain aware of the well as your nearest and dearest only needs of the military veterans that the good things with special emphasis on SA Legion supports and it is with great staying healthy. pleasure that I can report that the tak- The world is moving at a very fast ings for Poppy Day reached the record pace – what with Twitter, Instagram etc. figure of R105,000 which, in essence, – but, at Rosedale, we take the view means 100+ military veterans will be that we’re here to have fun and if it’s at a on the receiving end of the Legion’s wel- slower rate, then so be it. Which means, fare. You’ll agree that’s a great way to dear readers, that the committee is kick off the New Year! FUNCTIONS AND EVENTS THINKING OF YOU Whether it is in celebratory style (birthdays and an- That’s Entertainment niversaries) or maybe you’ve been poorly (sick or even hospitalised), he little ones from Odette Leach’s perhaps there’s some consolation in Kay-Dee Educare Centre enter- knowing that you’re very much in our Ttained the residents on Thursday thoughts, in particular to Jenny Jewell 6 December to a festive and her family on the passing of Syd season song-and-dance on 28 December. -

My European Recipe Book

My European Recipe Book Recipes collected by students and teachers during the COMENIUS-Project “Common Roots – Common Future” in the years 2010 - 2012 In the years 2010 – 2012 the following schools worked together in the COMENIUS-Project “COMMON ROOTS – COMMON FUTURE” - Heilig-Harthandelsinstituut Waregem, Belgium - SOU Ekzarh Antim I Kazanlak, Bulgaria - Urspringschule Schelklingen, Germany - Xantus Janos Kettannyelvu Idegenforgalmi Kozepiskola es Szakkepzo Iskola Budapest, Hungary - Fjölbrautaskolinn I Breidholti Reykjavik, Iceland - Sykkylven vidaregaaende skule Sykkylven, Norway - Wallace Hall Academy Thornhill, Scotland <a href="http://de.fotolia.com/id/24737519" title="" alt="">WoGi</a> - Fotolia.com © WoGi - Fotolia.com ~ 1 ~ During the project meetings in the participating countries the students and teachers were cooking typical meals from their country or region, they exchanged the recipes and we decided to put all these family recipes together to a recipe book. As the recipes are based on different measurements and temperature scales we have added conversion tables for your (and our) help. At the end of the recipe book you will find a vocabulary list with the most common ingredients for the recipes in the languages used in the countries involved in the project. For the order of recipes we decided to begin with starters and soups being followed by various main courses and desserts. Finally we have added a chapter about typical cookies and cakes. We learned during the project work, that making cookies yourself is not common in many of the countries involved in this project, but nevertheless many nice cookies recipes exist – we wanted to give them some space here and we hope that you will try out some of them! We have added a DVD which shows the making of some of the dishes during the meetings and also contains the recipes.