14 Leafy Spurge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Revised February 24, 2017 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org C ur Alleghany rit Ashe Northampton Gates C uc Surry am k Stokes P d Rockingham Caswell Person Vance Warren a e P s n Hertford e qu Chowan r Granville q ot ui a Mountains Watauga Halifax m nk an Wilkes Yadkin s Mitchell Avery Forsyth Orange Guilford Franklin Bertie Alamance Durham Nash Yancey Alexander Madison Caldwell Davie Edgecombe Washington Tyrrell Iredell Martin Dare Burke Davidson Wake McDowell Randolph Chatham Wilson Buncombe Catawba Rowan Beaufort Haywood Pitt Swain Hyde Lee Lincoln Greene Rutherford Johnston Graham Henderson Jackson Cabarrus Montgomery Harnett Cleveland Wayne Polk Gaston Stanly Cherokee Macon Transylvania Lenoir Mecklenburg Moore Clay Pamlico Hoke Union d Cumberland Jones Anson on Sampson hm Duplin ic Craven Piedmont R nd tla Onslow Carteret co S Robeson Bladen Pender Sandhills Columbus New Hanover Tidewater Coastal Plain Brunswick THE COUNTIES AND PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF NORTH CAROLINA Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org This list is dynamic and is revised frequently as new data become available. New species are added to the list, and others are dropped from the list as appropriate. -

Euphorbia Telephioides (Euphorbiaceae)

Genetic diversity within a threatened, endemic North American species, Euphorbia telephioides (Euphorbiaceae) Dorset W. Trapnell, J. L. Hamrick & Vivian Negrón-Ortiz Conservation Genetics ISSN 1566-0621 Conserv Genet DOI 10.1007/s10592-012-0323-4 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer Science+Business Media B.V.. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your work, please use the accepted author’s version for posting to your own website or your institution’s repository. You may further deposit the accepted author’s version on a funder’s repository at a funder’s request, provided it is not made publicly available until 12 months after publication. 1 23 Author's personal copy Conserv Genet DOI 10.1007/s10592-012-0323-4 RESEARCH ARTICLE Genetic diversity within a threatened, endemic North American species, Euphorbia telephioides (Euphorbiaceae) Dorset W. Trapnell • J. L. Hamrick • Vivian Negro´n-Ortiz Received: 23 September 2011 / Accepted: 20 January 2012 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2012 Abstract The southeastern United States and Florida which it occurs, Gulf (0.084), Franklin (0.059) and Bay support an unusually large number of endemic plant spe- Counties (0.033), were also quite low. Peripheral popula- cies, many of which are threatened by anthropogenic tions did not generally have reduced genetic variation habitat disturbance. As conservation measures are under- although there was significant isolation by distance. Rare- taken and recovery plans designed, a factor that must be faction analysis showed a non-significant relationship taken into consideration is the genetic composition of the between allelic richness and actual population sizes. -

Invasive Species: a Challenge to the Environment, Economy, and Society

Invasive Species: A challenge to the environment, economy, and society 2016 Manitoba Envirothon 2016 MANITOBA ENVIROTHON STUDY GUIDE 2 Acknowledgments The primary author, Manitoba Forestry Association, and Manitoba Envirothon would like to thank all the contributors and editors to the 2016 theme document. Specifically, I would like to thank Robert Gigliotti for all his feedback, editing, and endless support. Thanks to the theme test writing subcommittee, Kyla Maslaniec, Lee Hrenchuk, Amie Peterson, Jennifer Bryson, and Lindsey Andronak, for all their case studies, feedback, editing, and advice. I would like to thank Jacqueline Montieth for her assistance with theme learning objectives and comments on the document. I would like to thank the Ontario Envirothon team (S. Dabrowski, R. Van Zeumeren, J. McFarlane, and J. Shaddock) for the preparation of their document, as it provided a great launch point for the Manitoba and resources on invasive species management. Finally, I would like to thank Barbara Fuller, for all her organization, advice, editing, contributions, and assistance in the preparation of this document. Olwyn Friesen, BSc (hons), MSc PhD Student, University of Otago January 2016 2016 MANITOBA ENVIROTHON STUDY GUIDE 3 Forward to Advisors The 2016 North American Envirothon theme is Invasive Species: A challenge to the environment, economy, and society. Using the key objectives and theme statement provided by the North American Envirothon and the Ontario Envirothon, the Manitoba Envirothon (a core program of Think Trees – Manitoba Forestry Association) developed a set of learning outcomes in the Manitoba context for the theme. This document provides Manitoba Envirothon participants with information on the 2016 theme. -

Are All Flea Beetles the Same?

E-1274 Are All Phyllotreata cruciferae Flea Beetles Crucifer Flea Beetle Versus the Same? Leafy Spurge Flea Beetles Denise L. Olson Assistant Professor, Entomology Dept. Janet J. Knodel Extension Crop Protection Specialist, NCREC, NDSU Aphthona lacertosa “FLEA BEETLE” is a common name describing many species of beetles that use their enlarged hind legs to jump quickly when disturbed. The adults feed on the leaves of their host plants. Heavily fed-on leaves have a shot-hole appearance. The larvae (wormlike immature stage) usually feed on the roots of the same host plants as adults. Common flea beetles that occur in North Dakota include the Flea beetles crucifer flea beetle (Phyllotreata cruciferae) and the leafy spurge have enlarged flea beetles (Aphthona species). The crucifer flea beetle is a hind legs that non-native insect pest that accidentally was introduced into they use to jump North America during the 1920s. Phyllotreata cruciferae now quickly when can be found across southern Canada and the northern Great disturbed. Plains states of the United States. The leafy spurge flea beetles are non-native biological control agents and were introduced for spurge control beginning in the mid-1980s. These biological control agents have been released in the south-central prov- inces of Canada and in the Upper Great Plains and Midwest Crucifer flea beetle is states of the United States. Although P. cruciferae and Aphthona an exotic insect pest. species are both known as flea beetles and do look similar, they differ in their description, life cycle and preference of host plants. Leafy spurge flea beetle species are introduced biological control North Dakota State University, Fargo, North Dakota 58105 agents. -

CDA Leafy Spurge Brochure

Frequently Asked Questions About the Palisade Insectary Mission Statement How do I get Aphthona beetles? You can call the Colorado Department of We are striving to develop new, effective Agriculture Insectary in Palisade at (970) ways to control non-native species of plants 464-7916 or toll free at (866) 324-2963 and and insects that have invaded Colorado. get on the request list. We are doing this through the use of biological controls which are natural, non- When are the insects available? toxic, and environmentally friendly. We collect and distribute adult beetles in June and July. The Leafy Spurge Program In Palisade How long will it take for them to control my leafy spurge? The Insectary has been working on leafy Biological Control You can usually see some damage at the spurge bio-control since 1988. Root feeding point of release the following year, but it flea beetles are readily available for release of typically takes three to ten years to get in early summer. Three other insect species widespread control. have been released and populations are growing with the potential for future Leafy Spurge What else do the beetles feed on? distribution. All of the leafy spurge feeding The beetles will feed on leafy spurge and insects are maintained in field colonies. cypress spurge. They were held in Additional research is underway to explore quarantine and tested to ensure they would the potential use of soilborne plant not feed on other plants before they were pathogens as biocontrol agents. imported and released in North America What makes the best release site? A warm dry location with moderate leafy spurge growth is best. -

Petition for the Release of Aphthona Cyparissiae Against Leafy Spurge in the United States1

Reprinted with permission from: USDA-ARS, March 19, 1986, unpublished. Petition for the release of Aphthona cyparissiae against leafy spurge in the 1 United States ROBERT W. PEMBERTON Part I TO: Dr. R. Bovey, Dept. of Range Science USDA/ARS/SR Texas A&M University College Station, TX 77843 U.S.A. Enclosed are the results of the research on the flea beetle Aphthona cyparissiae (Chrysomelidae). This petition is composed of two parts. The first is the report “Aph- thona cyparissiae (Kock) and A. flava Guill. (Coleopera: Chrysomelidae): Two candi- dates for the biological control of cypress and leafy spurge in North America” by G. Sommer and E. Maw which the Working Group reviewed on Canada’s behalf. Copies of this report should be in the Working Group’s files. This research, which was done at the Commonwealth Institute of Biological Control’s Delémont, Switzerland lab, showed A. cyparissiae to be specific to the genus Euphorbia of the Euphorbiaceae. This result agrees with the literature and field records for A. cyparissiae, which recorded it from: Euphorbia cyparissias, E. esula, E. peplus, E. seguieriana, and E. virgata. The Sommer and Maw report also included information on A. cyparissiae’s taxonomic position, life history, laboratory biology, mortality factors, feeding effects on the host plants, the Harris scoring system, as well as a brief description of the target plant – leafy spurge (Euphorbia esula complex), a serious pest of the rangelands of the Great Plains of North America. Based on this research, the Working Group gave permission to release A. cyparissiae in Canada and to import it into the USDA’s Biological Control of Weeds Quarantine in Al- bany, California, for additional testing. -

An Evaluation of the Wetland and Upland Habitats And

AN EVALUATION OF THE WETLAND AND UPLAND HABITATS AND ASSOCIATED WILDLIFE RESOURCES IN SOUTHERN CANAAN VALLEY CANAAN VALLEY TASK FORCE SUBMl'l*IED BY: EDWIN D. MICHAEL, PH.D. PROFESSOR OF WILDLIFEMANAGEI\fENT DIVISION OF FORESTRY WEST VIRGINIA UNIVERSITY MORGANTOWN, WV 26506 December 1993 TABLB OP' CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION 6 OBJECTIVES 6 PROCEDURES 6 THE STUDY AREA Canaan Valley .... ..... 7 Southern Canaan Valley .... 8 Development and Land Use 8 Existing Environment Hydrology ........ 9 Plant Communities .... 11 1. Northern hardwoods . 11 2. Conifers ... 11 3. Aspen groves . 11 4. Alder thickets 12 5. Ecotone 12 6. Shrub savannah 12 7. Spiraea 13 8. Krummholz 13 9. Bogs ..... 13 10. Beaver ponds 13 11. Agriculture . l4 Vegetation of Southern Canaan Valley Wetlands 14 Rare and Endangered Plant Species 16 Vertebrate Animals 16 1. Fishes .. 16 2. Amphibians 18 3. Reptiles 19 4. Birds 20 5. Mammals 24 Rare and Endangered Animal Species 25 Game Animals 27 Cultural Values 28 Aesthetic Values 31 1. Landform contrast 31 2. Land-use contrast 31 3. Wetland-type diversity 32 4. Internal wetland contrast 32 5. Wetland size ... 32 6. Landform diversity .... 32 DISCUSSION Streams 32 Springs and Spring Seeps 34 Lakes . 35 Wetland Habitats 35 ii Wildlife 36 Management Potential 38 Off-road Vehicle Use 42 Fragmentation . 42 Cultural Values 44 Educational Values SIGNIFICANCE OF THE AREA OF CONCERN FOR FULFILLMENT OF THE CANAAN VALLEY NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE 1979 EIS OBJECTIVES 46 CONCLUSIONS .. 47 LITERATURE CITED 52 TABLES 54 FIGURES 88 iii LIST OF TABLES 1. Property ownerships of Canaan Valley ... ..... 8 2. -

St. Joseph Bay Native Species List

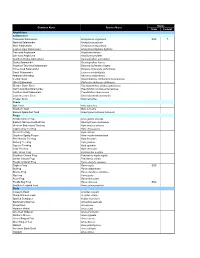

Status Common Name Species Name State Federal Amphibians Salamanders Flatwoods Salamander Ambystoma cingulatum SSC T Marbled Salamander Ambystoma opacum Mole Salamander Ambystoma talpoideum Eastern Tiger Salamander Ambystoma tigrinum tigrinum Two-toed Amphiuma Amphiuma means One-toed Amphiuma Amphiuma pholeter Southern Dusky Salamander Desmognathus auriculatus Dusky Salamander Desmognathus fuscus Southern Two-lined Salamander Eurycea bislineata cirrigera Three-lined Salamander Eurycea longicauda guttolineata Dwarf Salamander Eurycea quadridigitata Alabama Waterdog Necturus alabamensis Central Newt Notophthalmus viridescens louisianensis Slimy Salamander Plethodon glutinosus glutinosus Slender Dwarf Siren Pseudobranchus striatus spheniscus Gulf Coast Mud Salamander Pseudotriton montanus flavissimus Southern Red Salamander Pseudotriton ruber vioscai Eastern Lesser Siren Siren intermedia intermedia Greater Siren Siren lacertina Toads Oak Toad Bufo quercicus Southern Toad Bufo terrestris Eastern Spadefoot Toad Scaphiopus holbrooki holbrooki Frogs Florida Cricket Frog Acris gryllus dorsalis Eastern Narrow-mouthed Frog Gastrophryne carolinensis Western Bird-voiced Treefrog Hyla avivoca avivoca Cope's Gray Treefrog Hyla chrysoscelis Green Treefrog Hyla cinerea Southern Spring Peeper Hyla crucifer bartramiana Pine Woods Treefrog Hyla femoralis Barking Treefrog Hyla gratiosa Squirrel Treefrog Hyla squirella Gray Treefrog Hyla versicolor Little Grass Frog Limnaoedus ocularis Southern Chorus Frog Pseudacris nigrita nigrita Ornate Chorus Frog Pseudacris -

Integrated Noxious Weed Management Plan: US Air Force Academy and Farish Recreation Area, El Paso County, CO

Integrated Noxious Weed Management Plan US Air Force Academy and Farish Recreation Area August 2015 CNHP’s mission is to preserve the natural diversity of life by contributing the essential scientific foundation that leads to lasting conservation of Colorado's biological wealth. Colorado Natural Heritage Program Warner College of Natural Resources Colorado State University 1475 Campus Delivery Fort Collins, CO 80523 (970) 491-7331 Report Prepared for: United States Air Force Academy Department of Natural Resources Recommended Citation: Smith, P., S. S. Panjabi, and J. Handwerk. 2015. Integrated Noxious Weed Management Plan: US Air Force Academy and Farish Recreation Area, El Paso County, CO. Colorado Natural Heritage Program, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado. Front Cover: Documenting weeds at the US Air Force Academy. Photos courtesy of the Colorado Natural Heritage Program © Integrated Noxious Weed Management Plan US Air Force Academy and Farish Recreation Area El Paso County, CO Pam Smith, Susan Spackman Panjabi, and Jill Handwerk Colorado Natural Heritage Program Warner College of Natural Resources Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado 80523 August 2015 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Various federal, state, and local laws, ordinances, orders, and policies require land managers to control noxious weeds. The purpose of this plan is to provide a guide to manage, in the most efficient and effective manner, the noxious weeds on the US Air Force Academy (Academy) and Farish Recreation Area (Farish) over the next 10 years (through 2025), in accordance with their respective integrated natural resources management plans. This plan pertains to the “natural” portions of the Academy and excludes highly developed areas, such as around buildings, recreation fields, and lawns. -

Post-Hoc Evaluation of the Efficacy of Aphthona Iacertosa at Le Spurge Bi0conri:Ol Release Sites Abstract

DENSïN AND EFFICACY OF THE FLEA BEETLE APHTHONA UCERTûSA (ROSENHAUER), AN INTRODUCED BIOCONTROL AGENT FORLEAEV SPURGE, IN ALBERTA Andrea Ruth Kalischuk B. Sc., University of Lethbridge, 1997 A Thesis Submitted to the Council on Graduate Studies of the University of Lethbridge in Partial FuifiUment of the Requiremeats for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE LETHBRlDGE, ALBERTA MAY 2001 "~ndreaKalischuk, 200 1 uisiaons and Acqursitians et "iBib iographic Senricas se- biWographiques The author has granteâ a non- L'auteur a accordé une Licence non exclusive licence aüowing the exclusive permettant h la National LiTbrary of Canada to BibliotheqUe nationaie du Canada de reproduce, lm, distribute or sel1 reproduire, pr8teq distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownershrp of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts hmit Ni la thèse ni des substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimes reproduced without the author's ou antrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. DEDICATION " Yow reason and your passion are the mdder and the sails ofyour seafnring soul. Ifeitheryour sails or your rudder be broken, you can but toss and drif or else be held at a standrtill in mid-seas. For reason, ruling alone, is a force confining; and pasion, unattended, ir a flame that burns to ifsown destruction." (Kahlil Gibran, 1923) To my mother - thanks for mendimg the hysin my rudder and sails. -

New DNA Markers Reveal Presence of Aphthona Species (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) Believed to Have Failed to Establish After Release Into Leafy Spurge

Biological Control 49 (2009) 1–5 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Control journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ybcon New DNA markers reveal presence of Aphthona species (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) believed to have failed to establish after release into leafy spurge R. Roehrdanz a,*, D. Olson b,1, G. Fauske b, R. Bourchier c, A. Cortilet d, S. Sears a a Biosciences Research Laboratory, Red River Valley Agricultural Research Center, Agricultural Research Service, US Department of Agriculture, 1605 Albrecht Blvd, Fargo, ND 58105, United States b Department of Entomology, North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND, United States c Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Lethbridge, AB, Canada d Agricultural Resources Management and Development Division - Weed Integrated Pest Management Unit, Minnesota Department of Agriculture, St. Paul, MN, United States article info abstract Article history: Six species of Aphthona flea beetles from Europe have been introduced in North America for the purpose Received 28 September 2007 of controlling a noxious weed, leafy spurge (Euphorbia esula). In the years following the releases, five of Accepted 10 December 2008 the species have been recorded as being established at various locations. There is no evidence that the Available online 31 December 2008 sixth species ever became established. A molecular marker key that can identify the DNA of the five established species is described. The key relies on restriction site differences found in PCR amplicons Keywords: of a portion of the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase I gene. Three restriction enzymes are required to Flea beetles separate the immature specimens which are not visually separable. Adults which can be quickly sepa- Leafy spurge rated into the two black species and three brown species require only two restriction enzymes to resolve Euphorbia esula Aphthona the species. -

(Leafy Spurge), on a Native Plant Euphorbia Robusta

Non-target impacts of Aphthona nigriscutis, a biological control agent for Euphorbia esula (leafy spurge), on a native plant Euphorbia robusta John L. Baker, Nancy A.P. Webber and Kim K. Johnson1 Summary Aphthona nigriscutis Foudras, a biological control agent for Euphorbia esula L. (leafy spurge), has been established in Fremont County, Wyoming since 1992. Near one A. nigriscutis release site, a mixed stand of E. esula and a native plant, Euphorbia robusta Engelm., was discovered in 1998. During July of 1999, A. nigriscutis was observed feeding on both E. esula and E. robusta. A total of 31 E. robusta plants were located and marked on about 1.5 ha of land that had an E. esula ground-cover of over 50%. Eighty-seven percent of the E. robusta plants showed adult feeding damage. There was 36% mortality for plants with heavy feeding, 12% mortality for plants with light feeding, and no mortality for plants with no feeding. By August of 2002, the E. esula ground-cover had declined to less than 6% and the E. robusta had increased to 542 plants of which only 14 plants (2.6%) showed any feeding damage. For the four-year period, the E. esula ground-cover was inversely correlated to E. robusta density and posi- tively correlated to A. nigriscutis feeding damage, showing that as E. esula density declines so does Aphthona nigriscutis feeding on E. robusta. Keywords: Aphthona, density, Euphorbia, mortality, non-target impacts. Introduction established populations. These sites were monitored annually to assess the establishment of the bioagents. A parcel of land 4.8 km (3 miles) south-west of Lander, There was a strong contrast between the Majdic land Fremont County, Wyoming has been infested with and the Christiansen properties where the insects were Euphorbia esula (leafy spurge) for over 30 years.