Warning at Pearl Harbour: Leslie Grogan and the Tracking of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1941: World War II Context U.S

1941: World War II Context U.S. fascists opposed President Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) from the start. In 1933, “America’s richest businessmen were in a panic. Roosevelt intended to conduct a massive redistribution of wealth…[and it] had to be stopped at all costs. The answer was a military coup…secretly financed and organized by leading officers of the Morgan and du Pont empires.” A top Wall Street conspirator, Gerald MacGuire, said: “We need a fascist government in this country…to save the nation from the communists who want to tear it down and wreck all that we have built.”36 The Committee on Un-American Activities said: “Sworn testimony showed that the plotters represented no- table families — Rockefeller, Mellon, Pew, Pitcairn, Hutton and great enterprises — Morgan, Dupont, Remington, Ana- conda, Bethlehem, Goodyear, GMC, Swift, Sun.”37 FDR also faced “isolationist” sentiments from such millionaires, who shared Hitler’s hatred of communism and had financed Hitler’s rise to power, as George Herbert Walker and Prescott Bush, predecessors of the current presi- dent.38 William R.Hearst, newspaper magnate and mid- wife of the war with Spain, actually employed Hitler, Mus- On December 8, 1941, the day after the solini and Goering as writers. He met Hitler in 1934 and bombing of Pearl Harbour, President used Readers’ Digest and his 33 newspapers to support fas- Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the U.S. cism and to oppose America’s entry into the war.39 declaration of war on Japan. Japan is put into the wrong and makes the first bad move — overt move.”42 In Day of Deceit: The Truth about FDR and Pearl Harbor, Robert Stinnett notes: “On November 15, 1941,.. -

Matson Foundation 2014 Manifest

MATSON FOUNDATION 2014 MANIFEST THE 2014 REPORT OF THE CHARITABLE SUPPORT AND COMMUNITY ACTIVITIES OF MATSON, INC. AND ITS SUBSIDIARIES IN HAWAII, THE PACIFIC, AND ON THE U.S. MAINLAND. MESSAGE FROM THE CEO One of Matson’s core values is to contribute positively to Matson Foundation 2014 Leadership the communities in which we work and live. It is a value our employees have generously demonstrated throughout Pacific Committee our long, rich history, and one characterized by community Chair, Gary Nakamatsu, Vice President, Hawaii Sales service and outreach. Whether in Hilo, Hawaii or Oakland, Vic Angoco Jr., Senior Vice President, Pacific California or Savannah, Georgia, our employees have guided Russell Chin, District Manager, Hawaii Island Jocelyn Chagami, Manager, Industrial Engineering our corporate giving efforts to a diverse range of causes. Matt Cox, President & Chief Executive Officer While we were able to show our support in 2014 for 646 Len Isotoff, Director, Pacific Region Sales organizations that reflect the broad geographic presence of Ku’uhaku Park, Vice President, Government & Community Relations our employees, being a Hawaii-based corporation which has Bernadette Valencia, General Manager, Guam and Micronesia served the Islands for over 130 years, most of our giving was Staff: Linda Howe, [email protected] - directed to this state. In total, we contributed $1.8 million Ka Ipu ‘Aina Program Staff: Keahi Birch in cash and $140,000 of in-kind support. This includes two Adahi I ‘Tano Program Staff (Guam): Gloria Perez special environmental partnership programs in Hawaii and Guam, Ka Ipu ‘A- ina and Adahi I Tano’, respectively. Since its Mainland Committee inception in 2001, Ka Ipu ‘A- ina has generated over 1,000 Chair, David Hoppes, Senior Vice President, Ocean Services environmental clean-up projects in Hawaii and contributed Patrick Ono, Sales Manager, Pacific Northwest* Gregory Chu, Manager, Freight Operations, Pacific Northwest** over $1 million to Hawaii’s charities. -

2015 3Rd Quarter

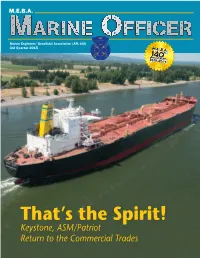

M.E.B.A. Marine Engineers’ Beneficial Association (AFL-CIO) 3rd Quarter 2015 That’s the Spirit! Keystone, ASM/Patriot Return to the Commercial Trades Faces around the Fleet Another day on the MAERSK ATLANTA, cutting out a fuel pump in the Red Sea. From left to right are 1st A/E Bob Walker, C/E Mike Ryan, 3rd A/E Clay Fulk and 2nd A/E Gary Triguerio. C/E Tim Burchfield had just enough time to smile for shutterbug Erin Bertram (Houston Branch Agent) before getting back to overseeing important operations onboard the MAERSK DENVER. The vessel is a Former Alaska Marine Highway System engineer and dispatcher Gene containership managed by Maersk Line, Ltd that is Christian took this great shot of the M/V KENNICOTT at Vigor Industrial's enrolled in the Maritime Security Program. Ketchikan, Alaska yard. The EL FARO sinking (ex-NORTHERN LIGHTS, ex-SS PUERTO RICO) was breaking news as this issue went to press. M.E.B.A. members past and present share the grief of this tragedy with our fellow mariners and their families at the AMO and SIU. On the Cover: M.E.B.A. contracted companies Keystone Shipping and ASM/Patriot recently made their returns into the commercial trades after years of exclusively managing Government ships. Keystone took over operation of the SEAKAY SPIRIT and ASM/Patriot is managing the molasses/sugar transport vessel MOKU PAHU. Marine Officer The Marine Officer (ISSN No. 10759069) is Periodicals Postage Paid at The Marine Engineers’ Beneficial Association (M.E.B.A.) published quarterly by District No. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 San Francisco, California * Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at San Francisco, CA, 1893-1953. M1410. 429 rolls. Boll Contents 1 May 1, 1893, CITY OF PUBLA-February 7, 1896, GAELIC 2 March 4, 1896, AUSTRALIA-October 2, 1898, SAN BLAS 3 October 26, 1898, ACAPULAN-October 1, 1899, INVERCAULA 4 November 1, 1899, CITY OF PUBLA-October 31, 1900, CURACAO 5 October 31, 1900, CURACAO-December 23, 1901, CITY OF PUEBLO 6 December 23, 1901, CITY OF PUEBLO-December 8, 1902, SIERRA 7 December 11, 1902, ACAPULCO-June 8, 1903, KOREA 8 June 8, 1903, KOREA-October 26, 1903, RAMSES 9 October 28, 1903, PERU-November 25, 1903, HONG KONG MARU 10 November 25, 1903, HONG KONG MARU-April 25, 1904, SONOMA 11 May 2, 1904, MELANOPE-August 31, 1904, ACAPULCO 12 August 3, 1904, LINDFIELD-December 17, 1904, MONGOLIA 13 December 17, 1904, MONGOLIA-May 24, 1905, MONGOLIA 14 May 25, 1905, CITY OF PANAMA-October 23, 1905, SIBERIA 15 October 23, 1905, SIBERIA-January 31, 1906, CHINA 16 January 31, 1906, CHINA-May 5, 1906, SAN JUAN 17 May 7, 1906, DORIC-September 2, 1906, ACAPULCO 18 September 2, 1906, ACAPULCO-November 8, 1906, KOREA Roll Contents Roll Contents 19 November 8, 1906, KOREA-Feburay 26, 1907, 56 April 11, 1912, TENYO MARU-May 28, 1912, CITY MONGOLIA OF SYDNEY 20 March 3, 1907, CURACAO-June 7, 1907, COPTIC 57 May 28, 1912, CITY OF SYDNEY-July 11, 1912, 21 May 11, 1907, COPTIC-August 31, 1907, SONOMA MANUKA 22 September 1, 1907, MELVILLE DOLLAR-October 58 July 11, 1912, MANUKA-August -

1962 November Engineers News

OPERATING ENGINEERS LOCI( 3 ~63T o ' .. Vol. 21 - No. 11 SANFRA~CISCO, ~AliFORN!~ . ~151 November1 1962 LE ·.·. Know Your . Friends greem~l1t on _And Your Enemies On.T o Trusts ;rwo ·trust instruni.ents for union-management' joint ad· ministration of Novel;llber 6 is Election Pay-,-a day that is fringe benefits negotiated by Operating En. gineers to e very American of voting age, but particularly Local 3 in the last industry agreement were· agreed upon in October. ' · ._. to men:tbers of Ope•rating Engineers Local 3. · The • -/ trust in~truments wen~ for the Operating Engineers · Voting~takirig a perso~al hand in the selection of the · Apprentice & J o urn e y m an ' · . men who w_ill ·make our laws an:d administer them on the . Training Fund and -for Health trust documents, Local 3 Bus. val~ ious levels of gov~minent-is a privilege· our~· aricestors· & Welfare benefits for pensioned Mgr. Al Clem commented: "The - -· fought: for. and thaC we . ~hould trel(lsure. But for most of Engineers. Negotiating Committee's discus- ·the . electorate. it's · simply that, a free man's privilege; not . · Agreement on the two trusts sions with the employers were an obligati_on. · . · . came well in advance_of January cordial and cooperative. We are - For members o{ Local 3, P,owev~r, _ lt's some•thing more 1, WB3, de~dlines which provided gratified that our members will ) han that; it comes cl(!?~r· t.9 b~, ing .<rb!ndiilg obligation. - that if union and employer .nego- be able to ·get the penefit of .· _If you'r~-::~dtpi- 1se f~y ti1i{ 'statement;· it might be in tiators couldn't acrree on either these trusts without delay and or der .::to"'ask:. -

Day of Deceit: the Truth About Fdr and Pearl Harbor Free

FREE DAY OF DECEIT: THE TRUTH ABOUT FDR AND PEARL HARBOR PDF Robert B. Stinnett | 399 pages | 08 May 2001 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9780743201292 | English | New York, United States [Day of Deceit: The Truth About FDR and Pearl Harbor] | By Robert B. New York: The Free Press,pages. Americans have always been fascinated Day of Deceit: The Truth about Fdr and Pearl Harbor conspiracy theories. At the top of our pantheon of paranoia are the myriad hypotheses surrounding the assassination of President John F. Close behind are the continuing arguments that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt deliberately provoked and allowed the destruction of the US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, in order to galvanize a reluctant American public into supporting national participation in World War II. This lingering suspicion is partly responsible for the recent drive to exonerate the commanders at Pearl Harbor, Admiral Husband Kimmel and Lieutenant General Walter Short, for their responsibility in the disaster on 7 December The latest book expounding this well-worn theory is Robert B. He has done some admirable and dogged primary research, filing innumerable requests under the Freedom of Information Act and spending many long hours searching in archives, and he demonstrates a journalist's knack for presenting a sensational story. The end result is an apparently damning indictment of FDR and his Cabinet, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, many naval officers above and below Admiral Kimmel, and the military intelligence community. Unfortunately the author failed to do much basic secondary Author: Dr. Conrad Crane. Date: Spring From: Parameters Vol. Publisher: U. Army War College. -

FDR and Pearl Harbor (Free Press, 2000), 258-260

CONFRONT THE ISSUE Almost as soon as the attacks occurred, conspiracy theorists began claiming that President Roosevelt had FDR AND prior knowledge of the assault on Pearl Harbor. Others have claimed he tricked the Japanese into starting a war with the United States as a “back door” way to go to war with Japan’s ally, Nazi Germany. However, PEARL after nearly 65 years, no document or credible witness has been discovered that prove either claim. Most HARBOR scholars view Pearl Harbor as the consequence of missed clues, intelligence errors, and overconfidence. The causes behind the Japanese attack are complex and date back to the 1930s, when Japan undertook a military/colonial expansion in China—culminating in a full-scale invasion in 1937. America opposed this expansion and used a variety of methods to try to deter Japan. During the late 1930s, FDR began providing limited support to the Chinese government. In 1940, Roosevelt moved the Pacific fleet to the naval base at Pearl Harbor as a show of American power. He also attempted to address growing tensions with Japan through diplomacy. When Japan seized southern French Indo-China in July 1941, Roosevelt responded by freezing Japanese Scroll down to view assets in the United States and ending sales of oil to Japan. Japan’s military depended upon American oil. select documents Japan then had to decide between settling the crisis through diplomacy or by striking deep into Southeast from the FDR Library Asia to acquire alternative sources of oil, an action that was certain to meet American opposition. and excerpts from the historical debate. -

Quiet Heroes Cover.Qxd

UNITED STATES CRYPTOLOGIC HISTORY Series IV World War II Volume 7 The Quiet Heroes of the Southwest Pacific Theater: An Oral History of the Men and Women of CBB and FRUMEL Sharon A. Maneki CENTER FOR CRYPTOLOGIC HISTORY NATIONAL SECURITY AGENCY Reprinted 2007 This monograph is a product of the National Security Agency history program. Its contents and conclusions are those of the author, based on original research, and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Security Agency. Please address divergent opinion or additional detail to the Center for Cryptologic History (EC). Page ii Table of Contents Foreword . v Preface . vii Acknowledgments . xii An Introduction to the Central Bureau Story . .1 Chapter 1: The Challenge of Reaching Australia . .3 Escaping from the Philippines: A View from the Navy . .3 Escaping from the Philippines: A View from the Army . .5 Traveling from Stateside . .7 Chapter 2: Challenges at Central Bureau Field Sections . .11 Mastering Japanese Intercept . .12 The Paradox of Life at a Field Site . .13 On the Move in New Guinea . .16 An American Perspective on Traffic Analysis . .18 Chapter 3: Cryptanalysts at Work in Central Bureau . .23 The Key to Success Was Teamwork . .25 The Joy of Discovery . .30 Putting Our Cryptanalytic Skills to the Test at Central Bureau 1942-1945 .34 Developing the Clues to Solve the Cryptanalytic Puzzle . .37 Chapter 4: Central Bureau: A Complete Signals Intelligence Agency . .39 The Trials and Tribulations of an IBM Operator . .39 Supporting Central Bureau’s Information Needs . .41 A Central Bureau J-Boy . .42 A Bizarre Experiment . -

Did Roosevelt Know About the Attack on Pearl Harbor Prior to December 7, 1941?

Did Roosevelt know about the attack on Pearl Harbor prior to December 7, 1941? Vallarie Larson Shaw Middle School Extended Controversial Issue Discussion Lesson Plan 0 Lesson Title: The Pearl Harbor Controversy Author Name: Vallarie Larson Contact Information: [email protected] Appropriate for Grade Level: 8-12 US History Standard(s)/Applicable CCSS(s): H1.[6-8].11 Explain the effects of WWI and WWII on social and cultural life in Nevada and the United States. H.4.[6-8].8 Discuss the effects of World War II on American economic and political policies. CCSS:Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources. CCSS:Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of the source distinct from prior knowledge or opinions. CCSS: Analyze the relationship between a primary and secondary source on the same topic. Discussion Questions: Did Roosevelt know about the attack on Pearl Harbor prior to December 7, 1941? Lesson Grabber: 1. Students should answer and write on the Pearl Harbor Scenario worksheet. Students can then share answers with class or small groups. 2. Show students clip from WWII documentary of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Clip shows the confusion and miscommunication that took place prior to the attack. Clip can be accessed from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nt13c3olXkU Engagement Strategy: Structured Academic Controversy. 1. Show the video “The Pearl Harbor Controversy” Video can be accessed in segments from You Tube or ordered from the History Channel. You Tube: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9yBd-gZvvsk http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HESlrW-tYSA&feature=relmfu http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yI23uHg0QFI&feature=relmfu The video is from the History Channel and examines some of the evidence of the controversy surrounding the Pearl Harbor attack. -

The Battle Over Pearl Harbor: the Controversy Surrounding the Japanese Attack, 1941-1994

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1995 The Battle Over Pearl Harbor: The Controversy Surrounding the Japanese Attack, 1941-1994 Robert Seifert Hamblet College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hamblet, Robert Seifert, "The Battle Over Pearl Harbor: The Controversy Surrounding the Japanese Attack, 1941-1994" (1995). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625993. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-5zq1-1y76 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BATTLE OVER PEARL HARBOR The Controversy Surrounding the Japanese Attack, 1941-1994 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Robert S. Hamblet 1995 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts '-{H JxijsJr 1. Author Approved, November 1995 d(P — -> Edward P. CrapoII Edward E. Pratt TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS......................................................................iv ABSTRACT..............................................................................................v -

Robert B. Stinnett Miscellaneous Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3c603258 No online items Inventory of the Robert B. Stinnett miscellaneous papers Finding aid prepared by Jessica Lemieux and Chloe Pfendler Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2008, 2014, 2021 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Inventory of the Robert B. 63006 1 Stinnett miscellaneous papers Title: Robert B. Stinnett miscellaneous papers Date (inclusive): 1941-2015 Collection Number: 63006 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 120 manuscript boxes, 1 oversize box(49.0 Linear Feet) Abstract: Memoranda and photographs depicting the aircraft carrier San Jacinto, naval personnel, prisoner of war camps, life at sea, scenes of battle, naval artillery, Tokyo, and the Pacific Islands during World War II. Correspondence, interviews, and facsimiles of intelligence reports, dispatches, ciphers and other records related to research on the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Creator: Stinnett, Robert B. Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access Box 4 restricted. The remainder of the collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1963. Additional material acquired in 2020. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Robert B. Stinnett miscellaneous papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Biographical Note Robert B. Stinnett was born March 31, 1924 in Oakland, California. During World War II, he served in the United States Navy as a photographer in the Pacific. -

Royal Air Force Historical Society Journal 28

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 28 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Photographs credited to MAP have been reproduced by kind permission of Military Aircraft Photographs. Copies of these, and of many others, may be obtained via http://www.mar.co.uk Copyright 2003: Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 2003 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361-4231 Typeset by Creative Associates 115 Magdalen Road Oxford OX4 1RS Printed by Advance Book Printing Unit 9 Northmoor Park Church Road Mothmoor OX29 5UH 3 CONTENTS A NEW LOOK AT ‘THE WIZARD WAR’ by Dr Alfred Price 15 100 GROUP - ‘CONFOUND AND…’ by AVM Jack Furner 24 100 GROUP - FIGHTER OPERATIONS by Martin Streetly 33 D-DAY AND AFTER by Dr Alfred Price 43 MORNING DISCUSSION PERIOD 51 EW IN THE EARLY POST-WAR YEARS – LINCOLNS TO 58 VALIANTS by Wg Cdr ‘Jeff’ Jefford EW DURING THE V-FORCE ERA by Wg Cdr Rod Powell 70 RAF EW TRAINING 1945-1966 by Martin Streetly 86 RAF EW TRAINING 1966-94 by Wg Cdr Dick Turpin 88 SOME THOUGHTS ON PLATFORM PROTECTION SINCE 92 THE GULF WAR by Flt Lt Larry Williams AFTERNOON DISCUSSION PERIOD 104 SERGEANTS THREE – RECOLLECTIONS OF No