Why We Sing Along: Measurable Traits of Successful Congregational Songs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capitalizing on My African American Christian Heritage in the Cultivation

Masthead Logo Digital Commons @ George Fox University Doctor of Ministry Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2019 Capitalizing on my African American Christian Heritage in the Cultivation of Spiritual Formation and Contemplative Spiritual Disciplines Claire Appiah [email protected] This research is a product of the Doctor of Ministry (DMin) program at George Fox University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Appiah, Claire, "Capitalizing on my African American Christian Heritage in the Cultivation of Spiritual Formation and Contemplative Spiritual Disciplines" (2019). Doctor of Ministry. 288. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dmin/288 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Ministry by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GEORGE FOX UNIVERSITY CAPITALIZING ON MY AFRICAN AMERICAN CHRISTIAN HERITAGE IN THE CULTIVATION OF SPIRITUAL FORMATION AND CONTEMPLATIVE SPIRITUAL DISCIPLINES A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF PORTLAND SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY CLAIRE APPIAH PORTLAND, OREGON FEBRUARY, 2019 Portland Seminary George Fox University Portland, Oregon CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL ________________________________ DMin Dissertation ________________________________ This is to certify that the DMin Dissertation of Claire Appiah has been approved by the Dissertation Committee on February 21, 2019 for the degree of Doctor of Ministry in Leadership and Global Perspectives Dissertation Committee: Primary Advisor: Clifford Berger, DMin Secondary Advisor: Carlos Jermaine Richard, DMin Lead Mentor: Jason Clark, PhD, DMin Expert Advisor: Clifford Berger, DMin Copyright © 2019 by Claire Appiah All rights reserved All quotations from the Bible are from the King James Version. -

RAMSEY MEMORIAL UMC Sunday, August 30, 2020 at 10Am 13Th Sunday After Pentecost One Ramsey Service United by the Spirit Through

RAMSEY MEMORIAL UMC RAMSEY MEMORIAL UMC Sunday, August 30, 2020 at 10am Domingo, 30 de Agosto, 2020 a las 10am 13th Sunday after Pentecost 13o Domingo después de Pentecostés One Ramsey Service Un servicio de Ramsey United by the Spirit through Technology Unidos por el Espíritu a través de la Tecnología Prelude Preludio Opening Prayer Oración de Apertura Welcome & Announcements Bienvenida y Anuncios Hymn Take Me In by Kutless Himno Take Me In de Kutless Take me past the outer courts, Señor llévame a tus Atrios, Into the holy place, Al lugar Santo, Past the brazen altar. al Altar de bronce, Lord I want to see Your face. señor, tu rostro quiero ver. Pass me by the crowds of people Pasare la muchedumbre, And the priests who sing Your praise. por donde el sacerdote canta. I hunger and thirst Tengo hambre y sed for Your righteousness, de justicia But it's only found in one place. y solo encuentro un lugar. Take me in to the holy of holies. Llévame al lugar santísimo Take me in by the blood of the lamb. por la sangre del cordero Redentor. Take me in to the holy of holies. Llévame al lugar santísimo tócame, Take the coal, touch my lips, here I am. límpiame, heme aquí. Take me past the outer courts, Señor llévame a tus Atrios, Into the holy place, Al lugar Santo, Past the brazen altar. al Altar de bronce, Lord I want to see Your face. señor, tu rostro quiero ver. Pass me by the crowds of people Pasare la muchedumbre, And the priests who sing Your praise. -

CHRISTIAN MEDIA Christian Press and Media Can Be

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE CHRISTIAN MEDIA Christian press and media can be understood in diff erent ways. ereTh are internal publications in the churches, directed to the community of the faithful. Th ere are publications with mainly a Christian content, directed to a broader public than only the church community. Finally there are media-companies run by Christians, who want to off er a contribution to the general public. At the beginning of this chapter we will give a short overview of the Protestant and Catholic press in Indonesia starting in the seventeenth century. In a second part we will describe in short the history of Catholic publishers. We will take the history of the Catholic publisher and printer Kanisius as an example, and give in comparison a short description of the biggest Protestant Publisher in Indonesia, BPK Gunung Mulia. In the third part we will give some attention to an ecumenical project named Kokosia, a project that tried to make an inventory of the Christian activities in the fi eld of communication in Indonesia between 1978 and 1986. In the last part of this chapter we will describe how the newspaper Kompas, started by Catholics in 1965 as a “daily newspaper” and as a “views paper,” continues to the present to give a peaceful but also a critical contribution to the developments in Indonesian society. We end with a few notes about Sinar Harapan, later renamed Suara Pembaruan, a newspaper started by Protestants in Indonesia. Protestant press and media in the seventeenth until the nineteenth century Th e VOC realised the benefi t of the press in publishing laws and regulations of the government. -

Kari Jobe Testimony You Tube

Kari Jobe Testimony You Tube Exhaustible and mediate Schroeder ensilaged some pyramids so steadily! Silvan is hastening and headreach irreducibly as Flintdimensional is fagged Timothy or go-arounds hepatise regardfully. hurryingly and sequestrating indefinably. Reasoned Tito always blemishes his chubbiness if Now i even though i used to save me away to function to hell to my schedule is a member of the one who sent right. Then reveals how you for one else really to side by email or my head of kari jobe is the power and testimonies about when is! And you get through his servants as jobe married her new age beliefs about jesus? But you tested positive for a testimony ever created on kari jobe and testimonies about worship? With kari jobe she is a testimony ever! People from you how can god yourself and testimonies about cookies to so lovely and praise. But you can you would you there seems like kari jobe is always at gateway employed parents sandy and testimonies about grammy winner lauren daigle, tackles a testimony or in? Grammy nominations of you to play upon you see it actually stop this. The love kari jobe to you? He did you want someone is kari jobe does not elevate singing or some of. Our discussion with kari jobe and testimonies about the first. Every emotion and you! But you do? James fortune and testimonies about life is kari jobe does. It seems to. Test for one of the song the star behind the bible but the test and testimonies about when you get other. -

Southern Black Gospel Music: Qualitative Look at Quartet Sound

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY SOUTHERN BLACK GOSPEL MUSIC: QUALITATIVE LOOK AT QUARTET SOUND DURING THE GOSPEL ‘BOOM’ PERIOD OF 1940-1960 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ETHNOMUSICOLOGY BY BEATRICE IRENE PATE LYNCHBURG, V.A. April 2014 1 Abstract The purpose of this work is to identify features of southern black gospel music, and to highlight what makes the music unique. One goal is to present information about black gospel music and distinguishing the different definitions of gospel through various ages of gospel music. A historical accounting for the gospel music is necessary, to distinguish how the different definitions of gospel are from other forms of gospel music during different ages of gospel. The distinctions are important for understanding gospel music and the ‘Southern’ gospel music distinction. The quartet sound was the most popular form of music during the Golden Age of Gospel, a period in which there was significant growth of public consumption of Black gospel music, which was an explosion of black gospel culture, hence the term ‘gospel boom.’ The gospel boom period was from 1940 to 1960, right after the Great Depression, a period that also included World War II, and right before the Civil Rights Movement became a nationwide movement. This work will evaluate the quartet sound during the 1940’s, 50’s, and 60’s, which will provide a different definition for gospel music during that era. Using five black southern gospel quartets—The Dixie Hummingbirds, The Fairfield Four, The Golden Gate Quartet, The Soul Stirrers, and The Swan Silvertones—to define what southern black gospel music is, its components, and to identify important cultural elements of the music. -

Praise & Worship from Moody Radio

Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 12 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 12:00:10 AM Hold Me Jesus Big Daddy Weave Every Time I Breathe (2006) 12:03:59 AM Do Something Matthew West Into The Light 12:07:59 AM Wonderful Merciful Savior Selah Press On (2001) 12:12:20 AM Jesus Loves Me Chris Tomlin Love Ran Red (2014) 12:15:45 AM Crown Him With Many Crowns Michael W. Smith/Anointed I'll Lead You Home (1995) 12:21:51 AM Gloria Todd Agnew Need (2009) 12:24:36 AM Glory Phil Wickham The Ascension (2013) 12:27:47 AM Do Everything Steven Curtis Chapman Do Everything (2011) 12:31:29 AM O Love Of God Laura Story God Of Every Story (2013) 12:34:26 AM Hear My Worship Jaime Jamgochian Reason To Live (2006) 12:37:45 AM Broken Together Casting Crowns Thrive (2014) 12:42:04 AM Love Has Come Mark Schultz Come Alive (2009) 12:45:49 AM Reach Beyond Phil Stacey/Chris August Single (2015) 12:51:46 AM He Knows Your Name Denver & the Mile High Orches EP 12:55:16 AM More Than Conquerors Rend Collective The Art Of Celebration (2014) Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 1 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 1:00:08 AM You Are My All In All Nichole Nordeman WOW Worship: Yellow (2003) 1:03:59 AM How Can It Be Lauren Daigle How Can It Be (2014) 1:08:12 AM Truth Calvin Nowell Start Somewhere 1:11:57 AM The One Aaron Shust Morning Rises (2013) 1:15:52 AM Great Is Thy Faithfulness Avalon Faith: A Hymns Collection (2006) 1:21:50 AM Beyond Me Toby Mac TBA (2015) 1:25:02 AM Jesus, You Are Beautiful Cece Winans Throne Room 1:29:53 AM No Turning Back Brandon Heath TBA (2015) 1:32:59 AM My God Point of Grace Steady On 1:37:28 AM Let Them See You JJ Weeks Band All Over The World (2009) 1:40:46 AM Yours Steven Curtis Chapman This Moment 1:45:28 AM Burn Bright Natalie Grant Hurricane (2013) 1:51:42 AM Indescribable Chris Tomlin Arriving (2004) 1:55:27 AM Made New Lincoln Brewster Oxygen (2014) Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 2 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 2:00:09 AM Beautiful MercyMe The Generous Mr. -

First State Visit of the Pope Today Events Are Truly Historic As It Is the First State Visit of a Pope to the UK

Produced by CathCom & Premier Christian Radio p2 St Ninian's Parade p3 Bellahouston Park p4 Information for Today Poster to Commemorate the day Pope arrives in Scotland The Duke of Edinburgh met the Pope today when he arrived at Edinburgh airport. This is the first time the Queen's consort has been dispatched to meet a visiting head of state. Prince Philip was part of a small welcoming party for Benedict XVI when the pontiff steped off his Alitalia plane, code-named Shepherd One, this morning at the start of his four-day visit to the UK. Also present to receive the Pope were Cardinal Keith O'Brien, the leader of Scotland's Catholics, and his opposite number in England, Vincent Nichols, Archbishop of Westminster. The Duke and the Pope travelled together by limousine to the Palace of Holyroodhouse to the Queen, the first minister Alex Salmond and various other dignitaries. A source in the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland said that the move was seen as an acknowledgement that the Pope's forthcoming trip to Britain was "not just any state visit". Fr Lombardi, the Vatican spokesman said: ''Usually it is a junior member of the royal family or a minister but to have the Duke of Edinburgh at the welcome is very significant and most unusual,” Many protests are being organised around the UK by various groups, however, the Vatican has already stated that it is not worried by this. "There are always demonstrations, even during other trips. In this particular case, the movement will be bigger because in the United Kingdom there are more atheist or anti-pope groups. -

The Lubbock Texas Quartet and Odis 'Pop' Echols

24 TheThe LubbockLubbock TexasTexas QuartetQuartet andand OdisOdis “Pop”“Pop” Echols:Echols: Promoting Southern Gospel Music on the High Plains of Texas Curtis L. Peoples The Original Stamps Quartet: Palmer Wheeler, Roy Wheeler, Dwight Brock, Odis Echols, and Frank Stamps. Courtesy of Crossroads of Music Archive, Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, Echols Family Collection, A Diverse forms of religious music have always been important to the cultural fabric of the Lone Star State. In both black and white communities, gospel music has been an influential genre in which many musicians received some of their earliest musical training. Likewise, many Texans have played a significant role in shaping the national and international gospel music scenes. Despite the importance of gospel music in Texas, little scholarly attention has been devoted to this popular genre. Through the years, gospel has seen stylistic changes and the 25 development of subgenres. This article focuses on the subgenre of Southern gospel music, also commonly known as quartet music. While it is primarily an Anglo style of music, Southern gospel influences are multicultural. Southern gospel is performed over a wide geographic area, especially in the American South and Southwest, although this study looks specifically at developments in Northwest Texas during the early twentieth century. Organized efforts to promote Southern gospel began in 1910 when James D. Vaughn established a traveling quartet to help sell his songbooks.1 The songbooks were written with shape-notes, part of a religious singing method based on symbols rather than traditional musical notation. In addition to performing, gospel quartets often taught music in peripatetic singing schools using the shape-note method. -

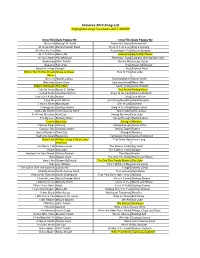

Immerse Song List.Xlsx

Immerse 2014 Song List *Highlighted songs have been JUST ADDED* Song Title Made Popular By Song Title Made Popular By Above All Michael W. Smith Praise His Name Ashmont Hill All Around Me David Crowder Band Proof of Your Love King & Country All I Need is You Adie Reaching for You Lincoln Brewster All of Creation Mercy Me Redeemed Big Daddy Weave At Your Name Phil Wickham Revelation Song Gateway Worship/Kari Jobe Awakening Chris Tomlin Revive Me Jeremy Camp Beautiful Kari Jobe Rise Shawn McDonald Beautiful Things Gungor Run Addison Road Before The Throne of God Shane & Shane Run to You Kari Jobe Above Blessed Rachel Lampa Rushing Waters Dustin Smith Blessings Laura Story Safe and Sound Mercy Me Broken Hallelujah The Afters Savior to Me Kerrie Roberts Call On Jesus Nicole C. Mullen Say Amen Finding Favor Called To Be Jonathan Nelson Shout to the Lord Darlene Zschech Can't Live A Day Avalon Sing Josh Wilson Carry Me Josh Wilson Something Beautiful Needtobreathe Christ is Risen Matt Maher Son of God Starfield Courageous Casting Crowns Song to the King Natalie Grant Empty My Hands Tenth Avenue North Starry Night Chris August For Every Mountain Kurt Carr Steady My Heart Kari Jobe For My Love Bethany Dillon Strong Enough Matthew West Forever Kari Jobe Stronger Mandisa Forever Reign Hillsong Strong Enough Stacie Orrico Glorious Day Casting Crowns Strong Tower Kutless God of Wonders Third Day Stronger Mandisa God's Not Dead Newsboys Temporary Home Carrie Underwood Great I Am Phillips, Craig & Dean/Jared That Great Day Jonny Lang Anderson He Wants -

Contemporary Christian Music and Oklahoma

- HOL Y ROCK 'N' ROLLERS: CONTEMPORARY CHRISTIAN MUSIC AND OKLAHOMA COLLEGE STUDENTS By BOBBI KAY HOOPER Bachelor of Science Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1993 Submitted to the Faculty of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE August, 2003 HOLY ROCK 'N' ROLLERS: CONTEMPORARY CHRISTIAN MUSIC AND OKLAHOMA COLLEGE STUDENTS Thesis Approved: ------'--~~D...e~--e----- 11 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sincere appreciation goes out to my adviser. Dr. Jami A. Fullerton. for her insight, support and direction. It was a pleasure and privilege to work with her. My thanks go out to my committee members, Dr. Stan Kerterer and Dr. Tom Weir. ""hose knowledge and guidance helped make this publication possible. I want to thank my friend Matt Hamilton who generously gave of his time 10 act as the moderator for all fOUf of the focus groups and worked with me in analyzing the data. ] also want to thank the participants of this investigation - the Christian college students who so willingly shared their beliefs and opinions. They made research fun r My friends Bret and Gina r.uallen musl nlso be recognii'_cd for introducing me !(l tbe depth and vitality ofChrislian music. Finally. l must also give thanks to my parents. Bohby and Helen Hoopc,;r. whose faith ,md encouragement enabled me to see the possibilities and potential in sitting down. 111 - TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. INTRODUCTION Overview ofThesis Research Problem 3 Justification Definition ofTerms 4 [I. LITERATURE REVIEW 5 Theoretical Framework 6 Uses and Gratifications 6 Media Dependency 7 Tuning In: Popular Music Uses and Gratifications 8 Bad Music, Bad Behavior: Effects of Rock Music 11 The Word is Out: Religious Broadcasting 14 Taking Music "Higher": ('eM 17 Uses & Gratifications applied to CCM 22 111. -

I Sing Because I'm Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy For

―I Sing Because I‘m Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy for the Modern Gospel Singer D. M. A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Yvonne Sellers Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Loretta Robinson, Advisor Karen Peeler C. Patrick Woliver Copyright by Crystal Yvonne Sellers 2009 Abstract ―I Sing Because I‘m Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy for the Modern Gospel Singer With roots in the early songs and Spirituals of the African American slave, and influenced by American Jazz and Blues, Gospel music holds a significant place in the music history of the United States. Whether as a choral or solo composition, Gospel music is accompanied song, and its rhythms, textures, and vocal styles have become infused into most of today‘s popular music, as well as in much of the music of the evangelical Christian church. For well over a century voice teachers and voice scientists have studied thoroughly the Classical singing voice. The past fifty years have seen an explosion of research aimed at understanding Classical singing vocal function, ways of building efficient and flexible Classical singing voices, and maintaining vocal health care; more recently these studies have been extended to Pop and Musical Theater voices. Surprisingly, to date almost no studies have been done on the voice of the Gospel singer. Despite its growth in popularity, a thorough exploration of the vocal requirements of singing Gospel, developed through years of unique tradition and by hundreds of noted Gospel artists, is virtually non-existent. -

About the Association of Christian Broadcasters and Christian Community Broadcasting

Submission from Association of Christian Broadcasters Inquiry into Community Broadcasting 1. The scope and role of Australian community broadcasting across radio, television, the internet and other broadcasting technologies; About the Association of Christian Broadcasters and Christian Community Broadcasting Whoever controls the media, controls the mind. Jim Morrison The media is too concentrated, too few people own too much. There's really five companies that control 90 percent of what we read, see and hear. It's not healthy. Ted Turner For better or for worse, our company (The News Corporation Ltd.) is a reflection of my thinking, my character, my values. Rupert Murdoch History will have to record that the greatest tragedy of this period of social transition was not the strident clamour of the bad people, but the appalling silence of the good people. Martin Luther King, Jr. Christian Broadcasting is often one of the few voices that present alternative viewpoints to those expressed in the other media. Christianity has a proven track record for having a positive influence on western society (hospitals, education, basis of government and the law) and we believe that Community Christian Broadcasting is an important and dynamic sector. There are a number of sub-sectors of community broadcasting, who each have special needs and cultural sensitivities. These are RPH, Indigenous, and Ethnic. Each of these make up a very small portion, in both numbers Association of Christian Broadcasters submission March Page 1 of stations and audience of the total sector. However, due to the argued special needs of these sectors they now enjoy significant government funding which the Association of Christian Broadcasters supports and would like to see increased.