Dr Simon Sandall – University of Winchester Folklore, Collective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forest-Of-Campus-Bus-Travel-1920.Pdf

Stagecoach Routes Continued Gloucestershire College 746 From Huntley, Mitcheldean & Drybrook Boxbush Manor House 07:51 Cinderford GlosCol 16:35 Travel to our Forest of Dean Campus Huntley White Horse 08:00 Drybrook Cross 16:43 Huntley Sawmill 08:02 Mitcheldean Dunstone Place 16:51 2019/20 Mitcheldean Lamb 08:12 Huntley Red Lion 17:02 Bus Timetables and Pricing Information Mitcheldean Dean Magna School 08:15 Churcham Bulley Lane 17:06 Drybrook Cross 08:25 Gloucester Transport Hub 17:20 Cinderford GlosCol 08:40 Michaels Travel Route Michaels Travel ROUTE 1—St Briavels AM PM St Briavels, playing fields bus stop 07:55 17:00 Clearwell, Village Hall 08:02 16:53 Sling Crossroads 08:07 16:48 Bream School 08:15 16:40 Parkend, The Woodman Inn 08:20 16:35 Cinderford Campus, Gloscol 08:35 16:20 Passes for this route must be bought in advance from Student Services. A full year pass costs £500. This can be paid via cash/card in Student Services. You can also set up a Direct Debit. A £100 deposit will be taken to secure the bus pass, We are pleased to announce that for the 2019/20 Academic Year, Stagecoach have agreed and then 8 monthly payments (October-May) of £50. to cover the majority of the routes from the Forest Of Dean and surrounding areas to our Forest of Dean Campus in Cinderford. Questions? This means that our students will benefit from the generous discounted rates that students can access with Stagecoach. If you have any queries or questions regarding transport to the Cinderford Campus or the funding available, please contact Student Services. -

Wales East of England London South West North East Yorkshire East

Berwick Wooler Alnwick Bellingham North East Newcastle Central The Sill at Hadrian’s Wall Edmundbyers Alston Ninebanks Skiddaw Keswick Hawse End Dufton Borrowdale Langdon Beck Buttermere Helvellyn Ennerdale Patterdale Grasmere Whitby Black Sail Langdale Hawes Boggle Hole Honister Hause Ambleside Osmotherley Dalby Forest Wasdale Hall Windermere Grinton Lodge Scarborough Eskdale Ingleton Helmsley Coniston Coppermines Coniston Holly How Kettlewell Yorkshire Hawkshead Slaidburn Malham York Haworth Beverley Friary Mankinholes North West Liverpool Central Manchester Castleton Losehill Hall Liverpool Albert Dock Edale Hathersage Conwy Rowen Ravenstor Eyam Idwal Cottage Snowdon Llanberis Sheen Sherwood Forest Wells-next-the-Sea Snowdon Ranger Betws-y-Coed Youlgreave Snowdon Bryn Gwynant Snowdon Pen-y-Pass Hartington Hall Hunstanton Alstonefield Sheringham Ilam Hall East Midlands Ironbridge Coalbrookdale Kings Thurlby All Stretton National Forest Ironbridge Coalport Borth Bridges Wilderhope Manor East of England Clun Mill Heart of England Wales Leominster Cambridge Blaxhall Poppit Sands Kington Stratford-upon-Avon Pwll Deri Newport Pembrokeshire Llangattock Milton Keynes St David's Llanddeusant Wye Valley London Broad Haven Brecon Beacons Oxford Brecon Beacons Danywenallt London Lee Valley London Central Manorbier St Briavels Castle Cotswolds Oxford St Rhossili St Pancras Port Eynon Streatley Jordans Thameside Gower Bristol Cardiff Central Earl's Court St Paul's Medway Bath Canterbury South East Tanners Hatch Cheddar Holmbury St Mary Minehead Cholderton Exford Street Elmscott Truleigh Hill Littlehampton Okehampton Bracken Tor South West Boscastle New Forest South Downs Lulworth Cove Brighton Tintagel Beer Totland Okehampton Eastbourne Litton Cheney Swanage Brighstone Treyarnon Bay Dartmoor Perranporth Portland Eden Project Portreath Boswinger Penzance Land's End Coverack Lizard. -

Ramblers Routes Ramblers Routes Britain’S Best Walks from the Experts Britain’S Best Walks from the Experts Central England

Ramblers Routes Ramblers Routes Britain’s best walks from the experts Britain’s best walks from the experts Central England Central England 07/02/2013 11:14 07 Broadway, Worcestershire 08 Newland, Gloucestershire l Distance 9km/5½ miles l Time 3½hrs l Type Hill l Distance 12km/7½ miles l Time 3hrs l Type Country and woodland NAVIGATION LEVEL FITNESS LEVEL NAVIGATION LEVEL FITNESS LEVEL walk magazine spring 2013 spring magazine walk walk magazine spring 2013 spring magazine walk Plan your walk Plan your walk l Birmingham l Worcester Brecon l NEWLAND BROADWAY l Hereford GWENT Gloucester l P WORCS Cardiff GLOS l l l Gloucester Bristol GLOS Bristol l l Swindon HY: FIONA BARLTRO HY: HY: NEIL COATES HY: P P WHERE: Circular walk from WHERE: Circular walk in the Broadway via St Eadburgha’s Wye Valley and Forest of PHOTOGRA Church and Broadway Tower. Dean, south of Monmouth. PHOTOGRA START/END: Broadway, war START/END: Redbrook, Broadway has been dubbed the 1. START The first part of this For centuries, the Forest of Dean take the steeper option ahead-L, memorial by the Green, Gloucestershire (SO536099). jewel of the Cotswolds, and it walk follows the well-signed was exploited for its coal, iron ore commencing a long, steady climb near the bottom of High TERRAIN: Field and does indeed epitomise this most Cotswold Way National Trail and ochre. Some of the wealth through woods. In time this levels Street (SP096375). woodland tracks, paths and attractive of quintessentially southwards. Very near the war created found its way into local beside the small concreted cap of TERRAIN: Field paths and quiet lanes, with two steady English regions. -

St Briavels Our Future in Our Hands

St Br1avels Our Future an our hands St Briavels ,l Parish Council Contents. ,., Introduction. .) 2 High Priority Actions. 4 2. 1 Crime & Security. 4 2.2 Transport. 5 ? ,., -·-' Environment. 6 2.4 Services. 7 2.5 Senior Citizens. 9 2.6 Under I s·s. 10 ,., .) The Results. 11 3. 1 Crime & Security. 11 3.2 Transport. 15 ,., ,., .) ..) Environment. 22 3.4 Services. 30 3.5 Senior Citizen Section. 40 3.6 Under 18's Section. 43 s Our Futu e 1n our hands. Introduction. Tn 200../ with the help ofthe SI Briavels Parish Council and the Gloucestershire Rural Community Council a group was.formed with the intention ofdrawing up a plan.for the Parish ofSt Briavels. The group was made up ofsix people.from the parish and two representatives.from the St Briavels Parish Council. In order lo help with lhe planning process a grant was applied.for andwas succes~fully obtained. This grant comprised approximately£../, 000 from the Countryside Agencyproviding that there was £1,000 donated in kind.from volunteers and £500.fi'·om the St Briavels Parish Council. The plan was intended to highlight all the areas that the parishioners were concerned about or would like to see changed in the parish. Tn order to.findout what the people thought o.fthe parish a question- 11aire was sent out to eve1y house and several meetings were held. The results o.fthe questionnaire and the meetings are shown in section 3. Now we have a plan, we have to put it into action and that s where you come in. -

Stowe Court Barns Stowe Hill (North Side) St Briavels Gloucestershire Archaeological Evaluation

Stowe Court Barns Stowe Hill (North Side) St Briavels Gloucestershire Archaeological Evaluation for The Crown Estate CA Project: 3999 CA Report: 12307 October 2012 Stowe Court Barns Stowe Hill (North Side) St Briavels Gloucestershire Archaeological Evaluation CA Project: 3999 CA Report: 12307 prepared by Charlotte Haines, Project Supervisor date 22 October 2012 checked by Cliff Bateman, Project Manager date 06 November 2012 Gail Stoten, Principal Consultant approved by date 07 November 2012 issue 01 This report is confidential to the client. Cotswold Archaeology accepts no responsibility or liability to any third party to whom this report, or any part of it, is made known. Any such party relies upon this report entirely at their own risk. No part of this report may be reproduced by any means without permission. © Cotswold Archaeology Building 11, Kemble Enterprise Park, Kemble, Cirencester, Gloucestershire, GL7 6BQ t. 01285 771022 f. 01285 771033 e. [email protected] © Cotswold Archaeology Stowe Court Barns, Stowe Hill (North Side), St Briavels, Gloucestershire: Archaeological Evaluation CONTENTS SUMMARY........................................................................................................................ 2 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 3 2. RESULTS (FIGS 2-14) ........................................................................................ 6 3. DISCUSSION...................................................................................................... -

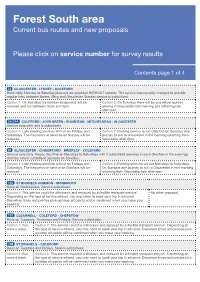

Forest South Area Current Bus Routes and New Proposals

Forest South area Current bus routes and new proposals Please click on service number for survey results Contents page 1 of 4 23 GLOUCESTER - LYDNEY - COLEFORD Runs daily. Monday to Saturday journeys are provided WITHOUT subsidy. The service was recently changed to provide regular links between Bream, Sling and Gloucester. Sunday service is subsidised. Option 1: On Sundays the number of journeys will be Option 2: On Sundays there will be one return journey reduced and run between 10am and 4pm. arriving in Gloucester mid morning and returning late afternoon. 24/24A COLEFORD - JOYS GREEN - RUARDEAN - MITCHELDEAN - GLOUCESTER Service runs daily and is subsidised. Option 1: Late evening services will run on Fridays and Option 2: Evening service to run daily but on Sundays one Saturdays. The frequency of services on Sunday will be journey to run to Gloucester in the morning returning from reduced. Gloucester after 4pm. 31 GLOUCESTER - CINDERFORD - BRIERLEY - COLEFORD Service runs daily. Hourly day time on Mondays to Saturdays with 2 subsidised journeys in each direction in the evenings and four return subsidised journeys on Sundays. Option 1: Late evening services will run on Fridays and Option 2: Evening services will run Mondays to Saturdays. Saturdays. The frequency of service on Sundays will be On Sundays one journey to run to Gloucester in mid morning reduced. returning from Gloucester late afternoon. 705 ST BRIAVELS COMMON - MONMOUTH Runs on Wednesdays. Service subsidised. Option 1: This service could be withdrawn and replaced by a flexible transport service*. No other proposal. Depending on the type of service offered, you may need to book your trip in advance. -

Coppers Green, the Common, St Briavels

Coppers Green, The Common, St Briavels Local Independent Professional Coppers Green, The Common, St Briavels, Lydney, Gloucestershire GL15 6SP. A charming extended stone built cottage with grounds in excess of half an acre, peacefully set within rolling countryside, enjoying superb far-reaching views over the Wye Valley, with close proximity to the old market towns of Chepstow and Monmouth. Entrance Hall Living Room with Exposed Stone Fireplace Conservatory Kitchen Utility Room Entrance porch to kitchen Study Cloakroom/Storage Inner Hall into additional rooms Master Bedroom with En-suite Shower Room Four further Bedrooms one with En-Suite Shower Room Family Bathroom Gated access to Sweeping Driveway Front Garden laid to lawn with paved Patio area Vegetable garden Rear lawned garden Outside WC Detached Double Garage Separate Stone Built Workshop Oil fired Central Heating Flexible accommodation that could provide self- contained accommodation Additional Land available by Separate Negotiation Situation: An opportunity to acquire a residential property in an accessible location in close proximity to the vibrant communities of Brockweir and St Briavels villages’, whilst the larger centres of Coleford, Lydney and Chepstow are all within convenient driving distance. At Chepstow, there is access via the M48 to the M4 motorway to Bristol, London and the M5 interchange to the West Country via the Severn Bridge; Newport, Cardiff and South Wales also via the M48/M4 or A48. At Lydney, the A48 leads to Gloucester with access to the M5, and access via Monmouth to the M50/M5. Agent’s Introduction: Coppers Green offers a rural yet accessible location, having been extended it provides spacious, flexible family accommodation with open views across the Wye Valley countryside. -

105. Forest of Dean and Lower Wye Area Profile: Supporting Documents

National Character 105. Forest of Dean and Lower Wye Area profile: Supporting documents www.gov.uk/natural-england 1 National Character 105. Forest of Dean and Lower Wye Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment White Paper1, Biodiversity 20202 and the European Landscape Convention3, we are revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas (NCAs). These are areas that share similar landscape characteristics, and which follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good decision-making framework for the natural environment. NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform theirdecision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The informationthey contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a landscape scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage broader partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will also help to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features that shape our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each area’s characteristics and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental Opportunity (SEOs) are suggested, which draw on this integrated information. The SEOs offer guidance on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. 1 The Natural Choice: Securing the Value of Nature, Defra NCA profiles are working documents which draw on current evidence and (2011; URL: www.official-documents.gov.uk/document/cm80/8082/8082.pdf) 2 knowledge. -

Keynote - Settlement Hierarchy

Keynote - Settlement Hierarchy Forest of Dean District Council: July 2011 (Core Document 15) Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 Regional Context 4 3 Local Context 5 4 Why is a Settlement Hierarchy needed? 7 4.1 The purpose of a Settlement Hierarchy 7 4.2 What are Settlements? 7 4.3 The role of the planning system 7 4.4 The Current Situation 8 5 National Policy 9 6 Methodology 10 6.1 Baseline 10 6.2 Settlement Services Table 11 7 Results 14 7.1 Settlement Hierarchy Map 14 7.2 Market Towns 16 7.2.1 Lydney 18 7.2.2 Cinderford 19 7.2.3 Coleford 20 7.2.4 Newent 22 7.3 Other Settlements 23 8 Conclusion 27 9 Appendix A: Policy Background 28 10 Appendix B: Comparative Matrix of Services & Facilities in the Forest of Dean Settlements 30 Forest of Dean District Council: July 2011 (Core Document 15) Keynote - Settlement Hierarchy Introduction 1 1 Introduction 1.1 The Local Development Framework (LDF) must carefully consider the way in which the settlements in the District relate one to another. The policies in the Core Strategy use these relationships and the general hierarchy of settlements. 1.2 The role of this paper is therefore to; Explain the role of national policy in the hierarchy Provide background evidence for a settlement hierarchy as used in the LDF 1.3 An understanding of the settlement hierarchy is important as the Local Development Framework (LDF) must set out a clear order of preference for the location of development. This needs to be robust, not just for the short term in the context of limited or no housing supply, but in the longer term when development requirements change. -

Case Study: Bridging the Gap

Case Study: Bridging the Gap The realities for communities, to deliver community-funded broadband improvements within budget and time? Is the commitment to communities driving UK Superfast broadband achievable? Or are the barriers of funding, red tape, monopolies, and delivery, just too difficult for most of us to overcome? Supporting Delivery of Gigabit Broadband The Hewelsfield and Brockweir parish is located in the West of the Forest of Dean District in the English county of Gloucestershire. Hewelsfield Broadband Group Hewelsfield Broadband Group was set up by residents to campaign for better broadband within the area. The existing infrastructure situation has resulted in substantial issues with broadband stability and performance; to compound matters with fixed broadband, the mobile network provides inadequate network coverage. Community Action The local residents have worked together to identify potential solutions to resolve the network issues. This included gaining local support, liaising with landowners Brockweir Bridge, River Wye, Western Border Hewelsfield and Brockweir Parish and finally contacting BT Openreach for a quote to install the infrastructure to deliver decent broadband (Circa £150k). Fastershire were approach, and have planned to roll out Gigabit Broadband to the area; this was not deemed to be rapid enough for the frustrated local community. Local Challenges Geography The parish is made up of a steep valley spreading up from the Wye at Bigsweir to a broader open rolling farmland where Hewelsfield is located. The local area is rural with two small village centres; there is a low population density and properties tend to be spread apart. Existing Infrastructure The local infrastructure is inadequate to provide the necessary broadband performance. -

Wye Valley Management 2004 Appendix

Wye Valley Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Management Plan 2004-2009 Appendix 1 ‘WYE VALLEY VIEWS’ RESPONSES The feedback and comments from the 14 public For the analysis the individual comments on the meetings and returned 132 Wye Valley View forms were grouped together into categories – questionnaires were entered into a detailed landscape, wildlife, peace & tranquillity, transport, database. While these responses cannot be access, internal (JAC) and other. The summary considered as a statistically valid sample of the table below shows the number of comments made resident or visiting population (25,000 population under each topic and expresses this as a or 2.5M visitors respectively) they do provide percentage of the total comments made on each some useful qualitative information. Numerical of the main ‘questions’. It can be seen that the analysis of the results is difficult due to the majority of comments were concerned with individual and qualitative and multiple nature of landscape (47%) and access (22%), with the comments made. For example on one form surprisingly, only 6% on wildlife. there could be comments on a range of issues in response to each question. The main questions considered here from the questionnaire are: 1) What do you consider to be the best features of the AONB? 2) What features would you most like to see conserved? 3) What features would you most like to see enhanced? 4) What other issues would you like to raise? Photo: AONB Unit Internal Landscape Wildlife Peace/ Transport Access Other Total JAC tranquillity -

The Wye Valley House

Broadleaf 65 19/9/05 8:46 am Page 32 NO 6 A WALK IN THE WOODS 1 L of farm and follow path past front of 5 3 ⁄2 MILES The Wye Valley house. Climb over fence and, keeping After white houses on R, bear L, derelict building on R, cross Offa’s Dyke passing seat. Follow this ancient footpath to go down R side of field. (For undulating path and go over stile to 1 1 3 ⁄2 OR 6 ⁄2 MILES thin meadow owned and managed shortcut, turn R at waymarker to rejoin leave woodland and follow edge of 2 OR 4 HOURS by the Woodland Trust.The tree-lined main route back along Offa’s Dyke meadow (spot the cowslips in spring). MODERATE (WITH STEEP SECTIONS) avenue continues past Coxbury Grove footpath.) Pass through broken wall by Follow path up through scrub at end and over stile. Continue on, crossing 3 on L, a steep grass field also owned by large pollarded tree, go down to stile more stiles, to enter Woodland Trust the Trust. and continue down through trees.Turn L property at the edge of Cadora 1 START along track at waymarker post. Woods. Leave this recently thinned From the Bell Inn, turn R before zebra 3 1 MILE If it is relatively dry underfoot, bear R woodland via the kissing gate and crossing, past Lavender Cottage on R. In wet weather, follow the track as it at five-bar gate and go through gap cross top edge of field, heading Follow Offa’s Dyke signpost up 67 bends to L (ignoring gate into woodland down into Cadora Grove (Woodland towards farmhouse.