A Simple and Reliable Method for Attaching Radio-Transmitters To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Article Appeared in a Journal Published by Elsevier. the Attached Copy Is Furnished to the Author for Internal Non-Commerci

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/authorsrights Author's personal copy Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 71 (2014) 149–156 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A multi-locus molecular phylogeny for Australia’s iconic Jacky Dragon (Agamidae: Amphibolurus muricatus): Phylogeographic structure along the Great Dividing Range of south-eastern Australia ⇑ Mitzy Pepper a, , Marco D. Barquero b, Martin J. Whiting b, J. Scott Keogh a a Division of Evolution, Ecology and Genetics, Research School of Biology, The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia b Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia article info abstract Article history: Jacky dragons (Amphibolurus muricatus) are ubiquitous in south-eastern Australia and were one of the Received 25 June 2013 -

Reproductive Ecology of the Mountain Dragon, Rankin/A (Tympanocryptis) Diemensis (Reptilia: Squamata: Agamidae) in Tasmania

Papers and Proceedings ofthe Royal Society of Tasmania, Volume 139, 2005 23 REPRODUCTIVE ECOLOGY OF THE MOUNTAIN DRAGON, RANKIN/A (TYMPANOCRYPTIS) DIEMENSIS (REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: AGAMIDAE) IN TASMANIA by Jemina Stuart-Smith, Roy Swain and Andrew Welling (with three tables and two text-figures) Stuart-Smith, J., Swain, R. & Welling, A. 2005 (16:xii): Reproductive ecology of the Mountain Dragon, Rankinia (Tympanocryptis) diemensis (Reptilia: Squamata: Agamidae) in Tasmania. Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 139: 23-28. https://doi.org/10.26749/rstpp.139.23 ISSN 0080-4703. School of Zoology, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 5, Tasmania, 7001 Australia.(J.S-S.*, R.S., AW). *Author for correspondence. The mountain dragon, Rankinia (Tympanocryptis) diemensis (Gray, 1841), is the only member of the Agamidae in Tasmania. It occurs in some of the coldest regions occupied by any dragon in Australia, and is found in a variety of habitats ranging from coastal heath to alpine scrub. This paper examines the reproductive ecology of R. diemensis in the most southerly range of its distribution, providing baseline data on timing of reproductive events, reproductive cycles, nesting behaviour and ovipositioning, clutch characteristics and incubation conditions. Winter torpor lasts approximately seven months with males emerging in early September and spermatogenesis occurring from September-November. Females emerge later, with vitcllogenesis occurring from September-December. Gravid females may be found between October and January, but females are non-vitcllogenic from late December until the following season. The firstclutch is typically laid from October-December, with a variable clutch size (2-11 eggs). Females store sperm and a second clutch may be laid fiveweeks after the first. -

Australian Capital Territory & Yass Valley Reptiles

Australian Capital Territory & Yass Valley Reptiles Geoff Robertson 4 June 2017 Turtle (1-2 species) Lizard Gecko (2) Legless lizard (4-5) Dragon (6) Gonna (2) Skink (32-35) Egernia group - chunky (9) Eugongylus group - striped (9-10) Sphenomorphus group - red (14) Snakes Blind (1) Total species = 57-66 Python (1?) Elapid (9-12) Murray (short-neck) turtle (above left) Emydura macquarii Eastern long-neck turtle (above right) Chelodina longicollis Lizards Monitors (goannas) Dragons Skinks Geckos Measuring length lizards & snakes: Legless TL - total length. lizards SVL - tip of the nose (snout) to vent. Dragons Physignathus lesueurii, Australia: 11 genera, 70 species. SVL 245 mm ACT/Yass: 5 genera, 6 species Common: Pogona barbata, Water dragon (top), Aust: 1 SVL 250 mm species. Eastern bearded dragon (bottom), Aust: 6 species. Jacky lizard or tree dragon. Three similar dragons Jacky (top), Nobbi (middle) and Mountain (bottom). SVL is Jacky - 120mm Nobbi - 84mm Mountain - 82mm However, all dragons (including water & bearded ) look similar when young. Photos top to bottom - Amphibolurus mutinous and A. nobbi, & Rankina diemensis. by Warren Saunders, John Wombey and Roger Farrow. Grassland earless dragon Eight earless dragon species in Australia. GED found in some natural grassland sites, climbs tussock grasses otherwise a ground dweller. Unlike other dragons, Tail slight/curls. Populations - ACT & southern Monaro. GED thought extinct, re-discovered, crashed in drought, captive breeding, future? Tympanocryptis pinguicolla. SVL 55mm. Bottom photo: Margaret Ning. Jacky dragon Bearded dragon Water dragon Nobbi dragon Mountain dragon Grassland earless dragon Gecko Australia: 18 genera & 111 species ACT/Yass: 2 species Stone gecko (right) Marble gecko (below) Diplodactylus vittatus, SVL 50mm Photo John Wombey Christinus marmaratus, SVL 70mm Photo Margaret Ning Legless lizards Related to geckos Australia: 7 genera & 38 species ACT/Yass: 2 genera & 5 species Unlike snakes: Lialis burtonis, SVL170mm Photo John Wombey • Large fleshy tongue (cf forked). -

Nelson Et Al No Highlight-1 Edit Changes

1 Receiver psychology and the design of the deceptive caudal luring signal of the death 2 adder 3 Ximena J. Nelsona,b* Daniel T. Garnettc, 1 Christopher S. Evansb, 2 4 5 aSchool of Biological Sciences, University of Canterbury 6 bCentre for the Integrative Study of Animal Behaviour, Macquarie University 7 cDepartment of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University 8 Received 6 July 2009 9 Initial acceptance 4 September 2009 10 Final acceptance 30 November 2009 11 MS. number: 09-00453R 12 13 *Correspondence: X. J. Nelson, School of Biological Sciences, University of Canterbury, 14 Private Bag 4800, Christchurch, New Zealand. 15 E-mail address: [email protected] (X. J. Nelson). 16 1D. T. Garnett is at the Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, 17 NSW 2109 Australia. 18 2C. S. Evans is at the Centre for the Integrative Study of Animal Behaviour, Macquarie 19 University, Sydney, NSW 2109 Australia. 20 1 21 Signal design can reflect the sensory properties of receivers. The death adder, Acanthophis 22 antarcticus, attracts prey by wriggling the distal portion of its tail (caudal luring). To 23 understand the design of this deceptive signal, we explored perceptual processes in a 24 representative prey species: the Jacky dragon, Amphibolurus muricatus. We used 3D 25 animations of fast and slow death adder luring movements against different backgrounds, to 26 test the hypothesis that caudal luring mimics salient aspects of invertebrate prey. Moving 27 stimuli elicited predatory responses, especially against a conspicuous background. To identify 28 putative models for caudal luring, we used an optic flow algorithm to extract velocity values 29 from video sequences of 61 moving invertebrates caught in lizard territories, and compared 30 these to the velocity values of death adder movements. -

Wollongong Campus Fauna Species List

FACTSHEET Wollongong Campus Fauna Species List The Wollongong Campus landscape provides habitat for a diverse range of animals. Animals that are known or potentially occur on campus are listed below. Key: # Introduced species, * Listed as a Vulnerable or threatened species in NSW, C- common, E - exotic, Res- resident, Br - breeds at UOW, M - migratory, V – visitor, P – potentially occurs onsite AMPHIBIANS Bleating tree frog Litoria dentate Res Eastern dwarf tree frog Litoria fallax Res Eastern froglet Crinia signifera C, Res Leaf green tree frog Litoria nudidigita Res Peron’s tree frog Litoria peronei Res Striped marsh frog Limnodynastes peronei Res Tyler’s tree frog Litoria tyleri Res Verreaux’s tree frog Litoria verreauxi Res REPTILES Common garden skink Lampropholis guichenoti C, Res Diamond python Morelia spilota Res Eastern blue tongue lizard Tilliqua scincoides C, Res Eastern long - necked turtle Chelondina longicollis Res Eastern small - eyed snake Cryptophis nigrescens Res Eastern tiger snake Notechis scutatus Res (escarpment) Eastern water dragon Physignathus lesurerii C, Res Eastern water skink Eulamprus quoyii C, Res Jacky dragon Amphibolurus muricatus Res Golden crowned snake Cacophis squamulosus Res Macquarie turtle Emydura macquarii Res Marsh (swamp) snake Hemiaspis signata Res Mustard bellied snake Drysdalia rhodogaster V Red - bellied black snake Pseudechis porphriacus Res Sheoak skink Cyclodomorphus michaeli Res Three - toed skink Saiphos equalis Res Weasel skink Saproscincus mustelinus Res MAMMALS Bush rat Rattus fuscipes -

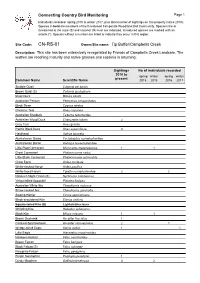

CN-RS-01 Owner/Site Name: Tip Buffer/Campbells Creek

Connecting Country Bird Monitoring Page 1 Individuals recorded spring 2015 to winter 2017, plus total number of sightings on this property (since 2010). Species in bold are members of the threatened Temperate Woodland Bird Community. Species rare or threatened at the state (S) and national (N) level are indicated. Introduced species are marked with an asterix (*). Species without a number are listed to indicate they occur in this region. Site Code: CN-RS-01 Owner/Site name: Tip Buffer/Campbells Creek Description: This site has been extensively revegetated by Friends of Campbells Creek Landcare. The wattles are reaching maturity and native grasses and cassinia is returning. Sightings No of individuals recorded 2010 to spring winter spring winter present Common Name Scientific Name 2015 2016 2016 2017 Stubble Quail Coturnix pectoralis Brown Quail (S) Coturnix ypsilophora Musk Duck Biziura lobata Australian Pelican Pelecanus conspicillatus Black Swan Cygnus atratus Chestnut Teal Anas castanea Australian Shelduck Tadorna tadornoides Australian Wood Duck Chenonetta jubata 2 Grey Teal Anas gracilis Pacific Black Duck Anas superciliosa 3 Hardhead Aythya australis Australasian Grebe Tachybaptus novaehollandiae Australasian Darter Anhinga novaehollandiae Little Pied Cormorant Microcarbo melanoleucos 1 1 Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo Little Black Cormorant Phalacrocorax sulcirostris Great Egret Ardea modesta White-necked Heron Ardea pacifica White-faced Heron Egretta novaehollandiae 2 2 Nankeen Night-Heron (S) Nycticorax caledonicus Yellow-billed -

Technique for Measuring Speed and Visual Motion Sensitivity in Lizards

Psicológica (2008), 29, 133-151. Technique for measuring speed and visual motion sensitivity in lizards Kevin L. Woo* and Darren Burke Macquarie University (Australia) Testing sensory characteristics on herpetological species has been difficult due to a range of properties related to physiology, responsiveness, performance ability, and the type of reinforcer used. Using the Jacky lizard as a model, we outline a successfully established procedure in which to test the visual sensitivity to motion characteristics. We incorporated modifications to traditional operant paradigms by using three video playback systems to deliver random-dot kinematogram motion stimuli coupled with salient computer-animated secondary reinforcers representative of biologically important appetitive stimuli. This procedure has the capacity to test other visual aspects in lizards as well as other non- human species using video playback and computer-animation techniques as experimental tools. Psychophysical studies that investigate the visual systems in various taxa are often challenging and require tedious trial-and-error testing before establishing a successful procedure (Ozlak & Wickens, 1999; Feldman & Balch, 2004). Some protocols have already been established for successful replication on similar taxa, or can provide a basis in which to test the sensory system in completely different species. However, not all available procedures are applicable to every species. Researchers must then develop a new method using basic conditioning paradigms. Limitations are also governed by the way in which the species is motivated to respond. These problematic features can be a function of the biological nature of the * Kevin L. Woo was supported by the Centre for the Integrative Study of Animal Behaviour postgraduate award, and the Australian Research Council. -

Use of Backpack Radio-Transmitters on Lizards of the Genus Aspidocelis (Squamata: Teiidae)

Other Contributions Miscellaneous Notes Use of backpack radio-transmitters on lizards of the genus Aspidocelis (Squamata: Teiidae) Radio-transmitters are used widely in field studies when tracking animals under natural conditions, especially when the spatial or temporal location of individuals provides information for behavioral studies and the weight of the transmitters has minimal adverse effects on their behavior. Radio telemetry has been used in ecological studies in lizards (e.g., Richmond, 1998; Warner et al., 2006; García-Bastida et al., 2012) and various methods have been proposed for securing the radio-transmitters (e.g., Fisher and Mut, 1995; Goodman, 2005; Goodman et al., 2009); not all methods, however, are suitable for the different sizes, shapes, or habits of the lizards under study. Lizards of the genus Aspidoscelis are slender, highly active, and agile, so the use of external equipment that is too heavy can compromise their activity and survival. For example, species in this genus usually seek refuge among rocks and holes in the ground, and the addition of an object strapped to their body might limit their mobility to enter or leave the shelters. Moreover, during annual periods of inactivity these lizards become fossorial in their habits, and therefore require the use of some lightweight material for attaching an external transmitter. Herein we describe a simple, inexpensive, and lightweight material that can be used for attaching an external radio-transmitter for telemetry field studies on lizards. This method involves a modification of that proposed by Gerner (2008) for the gecko Phelsuma guentheri, and is based on the use of a simple backpack, of low cost and high reliability, in which light-weight material is used. -

Incorporated

THE AUSTRALIAN SOCIETY OF HERPETOLOGISTS INCORPORATED NEWSLETTER 49 Published 29 September 2014 2 Letter from the editor I trust you found yourselves securely amused in the ever capable hands of that respectably amiable Professor Keogh and saucy Dr Mitzy during the 2014 ASH conference. The 2014 AGM was the first meeting I have missed since I attended my first ASH at 21 years old in Healesville Victoria. A time of a young and impressionable heart left seduced by Rick Shines, well… shine I suppose, a top a bald and knowledgeable head, awed by the insurmountable yet witty detail of Glenn Shea's trivia (not to mention that beard) and left speechless by the ever inappropriate, wildly handsome and ridiculously witty Mr Clemann. I welcome the newbys to a society that holds a unique place in Australian science. Where the brains and ideas of some of Australia's top scientists are corrupted by their inner herpetological brawn, where copious quantities of beer often leave even the most innocent of professors busting out the most quality of limbo attempts, break dance moves... or just plain naked. Where Conrad Hoskin becomes a lake Ayer dragon to avoid courtship rituals, where the obscure snores of Matthew Greenlees leave phylogenetists confused with analogous evolutionary traits, and where Mark Hutchinson’s intimate relationship with every single lizard in the entire country including coastal fringes and off shore islands, puts everyone to shame and anyone left to sleep. It is with deep regret and sheer delight that I could not join you this year, for my inner black mumma has met with my chameleon calling to leave my big island home and travel west to Madagascar where I am set up, working part time for University of Newcastle and part time for a local organisation called Madagasikara Voakajy for an indeterminate period. -

Grand Australia Part I: New South Wales & the Northern Territory September 28–October 14, 2019

GRAND AUSTRALIA PART I: NEW SOUTH WALES & THE NORTHERN TERRITORY SEPTEMBER 28–OCTOBER 14, 2019 A knock out Rose-crowned Fruit-Dove we found in Darwin perched out unusually brazenly. LEADERS: DION HOBCROFT AND JANENE LUFF LIST COMPILED BY: DION HOBCROFT VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM Our Australia tours have become so popular that we ran two VENT departures this year around the continent. The first was led by great birding friend and outstanding leader Max Breckenridge, well assisted by Barry Zimmer, one of our most highly regarded leaders. Janene and I led the second departure starting a week later. As usual, we started in Sydney at a comfortable hotel close to city attractions like the Opera House, Botanic Gardens, Art Gallery, and various museums. This included some good birding sites like Sydney Olympic Park some five miles west of the city. This young male Superb Lyrebird came walking past us in rainforest at Royal National Park. Our tour began with great cool weather, and in the park we were soon amongst the attractions with nesting Tawny Frogmouth a good start. There were plenty of waterbirds including Black Swan, Chestnut Teal, Hardhead, Australasian Darter, four species of cormorants, and three species of large rails (swamphen, moorhen, and coot). On the tidal lagoon, good numbers of Red-necked Avocets mingled about with a small flock of recently arrived migrant Sharp-tailed Sandpipers, while a dapper pair of adult Red-kneed Dotterels was very handy. Participants were somewhat “gobsmacked” by colorful Galahs, Rainbow Lorikeets, raucous Sulphur-crested Cockatoos, and their smaller cousin the Little Corella. -

Sex Determination in Reptiles

Chapter 1 Sex Determination in Reptiles Daniel A. Warner Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA of most organisms is determined by genetic factors located SUMMARY on sex-specific chromosomes. The sex-determining mechanisms (SDMs) of reptiles are remarkably diverse, ranging from systems that are under complete Research has since revealed far greater diversity in sex- genetic control to those that are highly dependent upon temper- determining mechanisms (SDMs). Karyological studies atures that embryos experience during development. Because have revealed a variety of sex-specific chromosomal reptiles exhibit a remarkable diversity of SDMs, this group arrangements (e.g., male vs. female heterogamety (Mittwoch, provides excellent models for addressing critical questions about 1996)). In many species, heteromorphic sex chromosomes the proximate mechanisms of sex determination, as well as its do not exist, but instead sex-determining factors lie on ecology and evolution. The goal of this chapter is to integrate autosomes. In other organisms, sex is determined by the studies from different disciplines (e.g., ecology, evolution, phys- ratio of X chromosomes to autosomes or the ploidy level iology, molecular biology) to broadly summarize the current of the zygote (Cook, 2002). During the latter half of the understanding of reptilian sex determination. This chapter is 20th century, the ubiquity of these genetic systems was divided into six topics that cover the (1) diversity of reptilian challenged by studies that demonstrate a role of environ- SDMs, (2) taxonomic distribution of SDMs, (3) molecular and physiological mechanisms underlying sex determination, mental factors in the sex-determination process. Indeed, in (4) timing of sex determination during embryogenesis, (5) many species, environmental conditions experienced ecology and evolution of reptilian SDMs, and (6) current gaps in during embryogenesis (rather than genotypic factors) our understanding of this field and where future research should be trigger the developmental cascade that eventually leads to directed. -

Agamidae: Amphibolurus Muricatus): Phylogeographic Structure Along the Great Dividing Range of South-Eastern Australia ⇑ Mitzy Pepper A, , Marco D

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 71 (2014) 149–156 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A multi-locus molecular phylogeny for Australia’s iconic Jacky Dragon (Agamidae: Amphibolurus muricatus): Phylogeographic structure along the Great Dividing Range of south-eastern Australia ⇑ Mitzy Pepper a, , Marco D. Barquero b, Martin J. Whiting b, J. Scott Keogh a a Division of Evolution, Ecology and Genetics, Research School of Biology, The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia b Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia article info abstract Article history: Jacky dragons (Amphibolurus muricatus) are ubiquitous in south-eastern Australia and were one of the Received 25 June 2013 first Australian reptiles to be formally described. Because they are so common, Jacky dragons are widely Revised 14 November 2013 used as a model system for research in evolutionary biology and ecology. In addition, their distribution Accepted 20 November 2013 along the Great Dividing Range of eastern Australia provides an opportunity to examine the influence Available online 6 December 2013 of past biogeographical processes, particularly the expansion and contraction of forest habitats, on the diversification of this iconic agamid lizard. We generated sequence data for two mitochondrial and three Keywords: nuclear DNA loci (4251base pairs) for 62 Jacky dragons sampled from throughout their distribution. Phy- Great Dividing Range logenetic analyses based on maximum likelihood and Bayesian species-tree methods revealed five geo- Phylogeography Reptile graphically structured clades separated by up to 6% mitochondrial and 0.7% nuclear sequence Agamidae divergence. We also quantified body proportion variation within and between these genetic clades for Eastern Australia more than 500 specimens and found no evidence of any significant differentiation in body proportions ⁄BEAST across their range.