Harvesting Near Bettyhill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caithness, Sutherland & Easter Ross Planning

THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL Agenda Item CAITHNESS, SUTHERLAND & EASTER ROSS PLANNING Report No APPLICATIONS AND REVIEW COMMITTEE – 17 March 2009 07/00448/FULSU Construction and operation of onshore wind development comprising 2 wind turbines (installed capacity 5MW), access track and infrastructure, switchgear control building, anemometer mast and temporary control compound at land on Skelpick Estate 3 km east south east of Bettyhill Report by Area Planning and Building Standards Manager SUMMARY The application is in detail for the erection of a 2 turbine windfarm on land to the east south east of Bettyhill. The turbines have a maximum hub height of 80m and a maximum height to blade tip of 120m, with an individual output of between 2 – 2.5 MW. In addition a 70m anemometer mast is proposed, with up to 2.9km of access tracks. The site does not lie within any areas designated for their natural heritage interests but does lie close to the: • Caithness and Sutherland Peatlands Special Area of Conservation (SAC) • Caithness and Sutherland Peatlands Special Protection Area (SPA) • Caithness and Sutherland Peatlands RAMSAR site • Lochan Buidhe Mires Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) • Armadale Gorge Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) • Kyle of Tongue National Scenic Area (NSA) Three Community Councils have been consulted on the application. Melvich and Tongue Community Councils have not objected, but Bettyhill, Strathnaver and Altnaharra Community Council has objected. There are 46 timeous letters of representation from members of the public, with 8 non- timeous. The application has been advertised as it has been accompanied by an Environmental Statement (ES), being a development which is classified as ‘an EIA development’ as defined by the Environmental Impact Assessment Regulations. -

Bettyhill Café and Tourist Information Centre Business Plan 2018

Bettyhill Café and Tourist Information Centre Business Plan 2018 1 | P a g e Executive Summary The Bettyhill Café and Tourist Information Centre is a full-service restaurant/cafe located at the east end of Bettyhill on the A836 adjacent to Strathnaver Museum. The restaurant features a full menu of moderately priced "comfort" food The Bettyhill Café and Tourist Information Centre (TIC) is owned by the Highland Council leased to and operated by Bob and Lindsay Boyle. Strathnaver Museum are undertaking an asset transfer to bring the facility into community ownership as part of the redevelopment of the Strathnaver Museum as a heritage hub for North West Sutherland. This plan offers an opportunity to review our vision and strategic focus, establishing the locality as an informative heritage hub for the gateway to north west Sutherland and beyond including the old province of Strathnaver, Mackay Country and to further benefit from the extremely successful NC500 route. 1 | P a g e Our Aims To successfully complete an asset transfer for a peppercorn sum from the Highland Council and bring the facility into community ownership under the jurisdiction of Strathnaver Museum. To secure technical services to draw appropriate plans for internal rearranging where necessary; to internally redevelop the interior of the building and have the appropriate works carried out. Seek funding to carry out the alterations and alleviate the potential flooding concern. Architecturally, the Café and Tourist Information Centre has not been designed for the current use and has been casually reformed to serve the purpose. To secure a local based franchise operation to continue to provide and develop catering services. -

Caithness and Sutherland Proposed Local Development Plan Committee Version November, 2015

Caithness and Sutherland Proposed Local Development Plan Committee Version November, 2015 Proposed CaSPlan The Highland Council Foreword Foreword Foreword to be added after PDI committee meeting The Highland Council Proposed CaSPlan About this Proposed Plan About this Proposed Plan The Caithness and Sutherland Local Development Plan (CaSPlan) is the second of three new area local development plans that, along with the Highland-wide Local Development Plan (HwLDP) and Supplementary Guidance, will form the Highland Council’s Development Plan that guides future development in Highland. The Plan covers the area shown on the Strategy Map on page 3). CaSPlan focuses on where development should and should not occur in the Caithness and Sutherland area over the next 10-20 years. Along the north coast the Pilot Marine Spatial Plan for the Pentland Firth and Orkney Waters will also influence what happens in the area. This Proposed Plan is the third stage in the plan preparation process. It has been approved by the Council as its settled view on where and how growth should be delivered in Caithness and Sutherland. However, it is a consultation document which means you can tell us what you think about it. It will be of particular interest to people who live, work or invest in the Caithness and Sutherland area. In preparing this Proposed Plan, the Highland Council have held various consultations. These included the development of a North Highland Onshore Vision to support growth of the marine renewables sector, Charrettes in Wick and Thurso to prepare whole-town visions and a Call for Sites and Ideas, all followed by a Main Issues Report and Additional Sites and Issues consultation. -

Economic Analysis of Strathy North Wind Farm

Economic Analysis of Strathy North Wind Farm A report to SSE Renewables January 2020 Contents 1. Executive Summary 1 2. Introduction 3 3. Economic Impact of Strathy North Wind Farm 6 4. Community Benefit 18 5. Appendix A – Consultations 23 6. Appendix B – Economic Impact Methodology 24 Economic Analysis of Strathy North Wind Farm 1. Executive Summary The development, construction and operation of Strathy North Wind Farm has generated substantial local and national impacts and will continue to do so throughout its operational lifetime and beyond. Strathy North Wind Farm, which is based in the north of Scotland, near Strathy in North Sutherland, was developed and built at a cost of £113 million (DEVEX/CAPEX). Operational expenditure (OPEX) and decommissioning costs over its 25-year lifetime are expected to be £121 million. The expected total expenditure (TOTEX) is £234 million. During the development and construction of Strathy North Wind Farm, it was estimated that companies and organisations in Scotland secured contracts worth £59.4 million. The area is expected to secure £100.6 million in OPEX contracts over the wind farm’s operational lifetime (£4.0 million annually). Overall the expenditure, including decommissioning, secured in Scotland is expected to be £165.0 million, or 73% of TOTEX. Highland is expected to secure £21.9 million in DEVEX/CAPEX contracts and £51.5 million in OPEX contracts (£2.1 million annually). Overall, Highland is expected to secure contracts worth £77.0 million, or 33% of TOTEX. Of this, £25.6 million, equivalent to 11% of TOTEX is expected to be secure in Caithness and North Sutherland. -

The Scottish Highlanders and the Land Laws: John Stuart Blackie

The Scottish Highlanders and the Land Laws: An Historico-Economical Enquiry by John Stuart Blackie, F.R.S.E. Emeritus Professor of Greek in the University of Edinburgh London: Chapman and Hall Limited 1885 CHAPTER I. The Scottish Highlanders. “The Highlands of Scotland,” said that grand specimen of the Celto-Scandinavian race, the late Dr. Norman Macleod, “ like many greater things in the world, may be said to be well known, and yet unknown.”1 The Highlands indeed is a peculiar country, and the Highlanders, like the ancient Jews, a peculiar people; and like the Jews also in certain quarters a despised people, though we owe our religion to the Hebrews, and not the least part of our national glory arid European prestige to the Celts of the Scottish Highlands. This ignorance and misprision arose from several causes; primarily, and at first principally, from the remoteness of the situation in days when distances were not counted by steam, and when the country, now perhaps the most accessible of any mountainous district in Europe, was, like most parts of modern Greece, traversed only by rough pony-paths over the protruding bare bones of the mountain. In Dr. Johnson’s day, to have penetrated the Argyllshire Highlands as far west as the sacred settlement of St. Columba was accounted a notable adventure scarcely less worthy of record than the perilous passage of our great Scottish traveller Bruce from the Red Sea through the great Nubian Desert to the Nile; and the account of his visit to those unknown regions remains to this day a monument of his sturdy Saxon energy, likely to be read with increasing interest by a great army of summer perambulators long after his famous dictionary shall have been forgotten, or relegated as a curiosity to the back shelves of a philological library. -

247 Torrisdale, Skerray, Sutherland Kw14 7Th Grid Reference Nc 679 616

THE WEST DEANERY, EWAN, HARRIS & Co., CASTLE STREET, SOLICITORS, NOTARIES, ESTATE AGENTS DORNOCH, SUTHERLAND IV25 3SN Alan D. Ewan Tel: (01862) 810686 Stephen D. Lennon Fax: (01862) 811020 Associate E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.ewan-harris.co.uk Legal Post: LP1-Dornoch 247 TORRISDALE, SKERRAY, SUTHERLAND KW14 7TH GRID REFERENCE NC 679 616 View from Croft For sale by private treaty and assignation of tenancy, the croft tenancy of Torrisdale, Skerray, on the north coast of Sutherland. The croft extends to 3.45acres with a share in common grazings which amounts to 74.37acres. There is presently no house upon the croft but a grant may be available to construct such a house and for agricultural improvements. Enquiries should be made through the Rural Payments Inspections Directorate, Crofters Commission and other responsible authorities. The croft entrance scheme is available in the area and again enquiries should be made to the Crofters Commission in that regard by potential purchasers. Potential purchasers should also note that croft assignations must be approved by the Crofters Commission. The Landlord is Sutherland Estate and the rent for the Croft and Common Grazings is currently £26 per year but may be subject to a review in the future. Any potential purchaser would have to obtain their own Planning Permission and Building Warrant in respect of construction of any dwelling house or any other structure requiring such Consents in respect of the property. Entry: By arrangement Viewings: Strictly by appointment through the Subscribers. Price: Offers over £16,000 in Scots Legal Form are invited. -

95 Kirtomy.Indd

Young Young Robertson Robertson & Co. solicitors • estate agents & Co. 95 KirtoMY, BettYHILL, THURSO 29 TRAILL STREET THURSO KW14 8EG tel: 01847 896177 Superb opportunity to purchase this delightful two bedroom property with extensions, fax: 01847 896358 detached bothy and various outbuildings. Situated in an elevated location enjoying [email protected] wonderful sea and coastal views across the valley the property benefits from solid fuel youngrob.co.uk central heating and predominantly uPVC double glazing. An idyllic Highland retreat, the property has been lovingly restored throughout and boasts fine views from all of the windows with the living room appreciating panoramic views. There is a contemporary 21 BRIDGE STREET fitted galley kitchen that leads off the snug/dining area which has a cosy multi-fuel stove. WICK KW1 4AJ There is a large modern bathroom off the main hallway with large shower bath and two tel: 01955 605151 fitted hand basins. Upstairs are two double bedrooms off the landing. Outside is ample off fax: 01955 602200 road parking, attractive garden grounds with raised flower beds, a pond, timber shed, bike [email protected] store, kennels and a large stable. An attractive stone detached bothy would be ideal for youngrob.co.uk conversion into a study or additional living accommodation subject to suitable planning consents. Only a short drive from Bettyhill the area is popular with nature lovers, fishers, walkers, beach-goers or for simple relaxation viewing is highly recommended. caithnessproperty.co.uk f FIXED PRICE £150,000 Hallway Postcode Glazed uPVC front door. Tiled flooring. Under stairs storage KW14 7TB cupboards. -

Fearchar Lighiche and the Traditional Medicines of the North

FEARCHAR LIGHICHE AND THE TRADITIONAL MEDICINES OF THE NORTH Mary Beith FEARCHAR BEATON: LEGEND & REALITY On the 5 March 1823, one John Kelly sent a letter from Skye to South Queensferry summarising three traditional Highland stories, the second of which related to: Farquaar Bethune called in Gaelic Farquhar Leich [correctly: Fearchar Lighiche, Fearchar the Healer] which signifies the curer of every kind of diseases, and which knowledge he received from a book printed in red in which had descended in heritable succesion and is now in the posession of Kenneth Bethunne ... of Waterstane [Waterstein) in Glendale, and which they contain both secret and sacred;- what instructions are contained therein are descriptive of the virtues of certain herbs in particular which he denied having any equal, nor being produced by any other country by Skye, it has been examined by Botanists from London and elsewhere and its non-affinity to any other confirmed. He was gifted with prophecy, and held conf[ erence] with the Brutal [natural] creation in that was quite a prodigy. This is only an outline of him. What Kelly lacked in grammar and spelling is irrelevant; what is pertinent is that his remarks about Fearchar Lighiche neatly encapsulate the tangle of fact, legend and mystery in which the old Highland healers, official and unofficial alike, were held in awe by their contemporaries and subsequent generations. The Fearchar of Kelly's note would have been a Beaton of Husabost in Skye, a notable family of hereditary, trained physicians who practised in the island from the 15th to the early 18th century, several of whom where named Fearchar. -

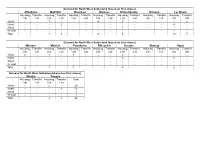

Demand for North West Sutherland (Based on First Choice) Altnaharra

Demand for North West Sutherland (based on first choice) Altnaharra Bettyhill Drumbeg Durness Kinlochbervie Kylesku Lochinver Housing Transfer Housing Transfer Housing Transfer Housing Transfer Housing Transfer Housing Transfer Housing Transfer List List List List List List List List List List List List List List 1 bed - - 1 - - - 4 - 3 - - - 7 5 2 bed - - - 2 - - - - - - - - 4 - 3 bed - - - - - - - - 1 - - - - - 4+ bed - - - - - - - - - - - - 1 - Total - - 1 2 - - 4 - 4 - - - 12 5 Demand for North West Sutherland (based on first choice) Melness Melvich Portskerra Rhiconich Scourie Skerray Stoer Housing Transfer Housing Transfer Housing Transfer Housing Transfer Housing Transfer Housing Transfer Housing Transfer List List List List List List List List List List List List List List 1 bed 2 - 1 - 1 - - - 2 - - - - - 2 bed - - - - - - - - 3 - - - 2 - 3 bed - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4+ bed - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Total 2 - 1 - 1 - - - 5 - - - 2 - Demand for North West Sutherland (based on first choice) Strathy Tongue Housing Transfer Housing Transfer Total List List List List 1 bed - - 2 - 28 2 bed - - - 1 12 3 bed - - - - 1 4+ bed - - - - 1 Total - - 2 1 42 Demand for North West Sutherland (using all choices) Altnaharra Bettyhill Drumbeg Durness Kinlochbervie Kylesku Lochinver Housing Transfer Housing Transfer Housing Transfer Housing Transfer Housing Transfer Housing Transfer Housing Transfer List List List List List List List List List List List List List List 1 bed 1 1 7 3 1 - 8 - 5 2 2 1 13 8 2 bed - - 1 2 3 - 1 - 1 - - - 7 1 3 -

Highland Health Board

NHS Highland Board 31 May 2016 Item 4.9 UPDATE ON MAJOR SERVICE REDESIGN PROJECTS Report by Gill McVicar, Director of Operations (North and West), Georgia Haire, Deputy Director of Operations (South and Mid) and Maimie Thompson (Head of PR and Engagement) on behalf of Deborah Jones, Director of Strategic Commissioning, Planning and Performance The NHS Highland Board is asked to: • Consider the proposals to redesign services for the North Coast (Sutherland), approve that the changes constitute major service change; endorse the pre- consultation work and options appraisal process and approve the draft consultation materials; • Note the update on progress with developing the business case for major redesign of services for Badenoch and Strathspey 1. Background and summary Services provided by the NHS need to change to ensure they meet the future needs of the changing population, particularly the increasing ageing population of Scotland and the number of people with long-term health conditions. There are additional challenges facing NHS Highland linked to geography, recruitment, staff retention and in some cases history. In addition there is a pressing need to develop more community services, facilitate greater community resilience and modernise and rationalise our estate. Notably at the time the major service change projects got underway in 2012/13 the backlog maintenance was some £70million. As set out in NHS Highland’s 10 year operational strategy, work is ongoing to transform models of care and services. The transformations of services -

SUTHERLAND Reference to Parishes Caithness 1 Keay 6 J3 2 Thurso 7 Wick 3 Olrig 8 Waiter 4 Dunnet 9 Sauark 5 Canisbay ID Icajieran

CO = oS BRIDGE COUNTY GEOGRAPHIES -CD - ^ jSI ;co =" CAITHNESS AND SUTHERLAND Reference to Parishes Caithness 1 Keay 6 J3 2 Thurso 7 Wick 3 Olrig 8 Waiter 4 Dunnet 9 SaUark 5 Canisbay ID IcaJieran. Sutherland Durnesx 3 Tatujue 4 Ibrr 10 5 Xildsjnan 11 6 LoiK 12 CamJbriA.gt University fi PHYSICAL MAP OF CAITHNESS & SUTHERLAND Statute Afiie* 6 Copyright George FkOip ,6 Soni ! CAITHNESS AND SUTHERLAND CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS C. F. CLAY, MANAGER LONDON : FETTER LANE, E.C. 4 NEW YORK : THE MACMILLAN CO. BOMBAY | CALCUTTA !- MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD. MADRAS J TORONTO : THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, LTD. TOKYO : MARUZEN-KABUSHIKI-KAISHA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED CAITHNESS AND SUTHERLAND by H. F. CAMPBELL M.A., B.L., F.R.S.G.S. Advocate in Aberdeen With Maps, Diagrams, and Illustrations CAMBRIDGE AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS 1920 Printed in Great Britain ly Turnbull &* Spears, Edinburgh CONTENTS CAITHNESS PACK 1. County and Shire. Origin and Administration of Caithness ...... i 2. General Characteristics .... 4 3. Size. Shape. Boundaries. Surface . 7 4. Watershed. Rivers. Lakes . 10 5. Geology and Soil . 12 6. Natural History 19 Coast Line 7. ....... 25 8. Coastal Gains and Losses. Lighthouses . 27 9. Climate and Weather . 29 10. The People Race, Language, Population . 33 11. Agriculture 39 12. Fishing and other Industries .... 42 13. Shipping and Trade ..... 44 14. History of the County . 46 15. Antiquities . 52 1 6. Architecture (a) Ecclesiastical . 61 17. Architecture (6) Military, Municipal, Domestic 62 1 8. Communications . 67 19. Roll of Honour 69 20. Chief Towns and Villages of Caithness . 73 vi CONTENTS SUTHERLAND PAGE 1. -

Crofters' Common Grazings in Scotland

Crofters' Common Grazings in Scotland By JAMES R. COULL N temperate Europe, the utilization of rough or unimproved land for grazing in common has been for centuries a feature of the traditional I economy---especially in regions of hill and mountain; indeed the use of hill grazings in such regions as the Highlands has been the stamp of adjust- ment to environment of economies dependent principally on stock rearing. In the old way in the crofting districts, the stock had to exist mainly on the hill, although they also grazed the inbye lands of townships after the harvest had been gathered; this is changing somewhat, now that croft land is used more for producing food for animals rather than people, although the hill grazings are still of vital importance. Some idea of the extent and importance of hill land may be got from the ratios of inbye to outbye land computed by F. Fraser Darling: this ratio is 1:12.5 in the Outer Hebrides, I : 2o in Skye, and rises as high as I : 85 in Wester Ross and I : 9o ill the North-West Main- land. 1 The survival of common land, along with the ways of utilization, is cer- tainly not peculiar to the Scottish Highlands. Thus there are more than 4, 5°o units of common land totalling some I½ million acres in England and Wales, and significantly most of it is in hill areas like the mountains of Wales and the Lake District. ~W. G. Hoskins has pointed out that commons are among the most ancient institutions of England? It is also known as far apart as Norway and Greece.