Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ssrooms and Seminar Halls

Self Study Report of MAR BASELIOS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AND SCIENCE SELF STUDY REPORT FOR 1st CYCLE OF ACCREDITATION MAR BASELIOS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AND SCIENCE MAR BASELIOS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AND SCIENCE, NELLIMATTOM P.O., KOTHAMANGALAM, ERNAKULAM DISTRICT. 686693 www.mbits.edu.in Submitted To NATIONAL ASSESSMENT AND ACCREDITATION COUNCIL BANGALORE August 2019 Page 1/124 20-11-2019 11:09:10 Self Study Report of MAR BASELIOS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AND SCIENCE 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 INTRODUCTION Mar Baselios Institute of Technology and Science [MBITS], was established in 2009 as the 6th venture in the Educational field under the auspices of Mar Thoma Cheria Pally Kothamangalam, which is a 6th century old parish church & pilgrim centre with the profound and continued Blessings of Saint Eldho Mar Baselios. The starting of MBITS has added one more golden feather to the Mar Basil Group of Institutions which was originated in 1936, with the establishment of Mar Basil School at Kothamangalam. The Institute is managed by Mar Baselios Educational and Charitable Trust led by committed stalwarts of the Church, Mar Thoma Cheria Pally. MBITS stands supreme in the field of technical education with a high level of excellence and quality in education along with good discipline and placement records. The atmosphere in the institute truly reflects the motto “Wisdom Crowns Knowledge”, thanks to the abundant blessings of the patron saint. The Institute is located at a scenic and serene place near Kothamangalam beside NH-85. The Institute is approved by AICTE and is affiliated to APJ Abdul Kalam Technological University,Kerala. -

Amrita Kiranam Nov 2018

AMRITA KIRANAM a snapshot and journal of happenings @ Amrita School of Arts and Sciences, Kochi No. 14 | Vol. 16 | November 2018 inside............ 2 Inauguration of Academic Activities and 16th Vidyamritam Series 3 Amrita Values Programme (AVP) and Social Awareness Campaign (SAC) 4 Graduation Day 2018 5 Swachhata Hi Seva 6 Kerala Piravi - Malayala Dinacharanam 2018 7 Department of Computer Science and IT Hands on Workshop on Python 8 Department of Commerce and Management Workshop on The Art of Writing Effective Research Papers 8 National Seminar on Goods and Services Tax (GST) 9 Department of Visual Media and Communication International Workshop on Photography 10 Department of Mathematics Publications, Paper Presentations 11 Department of English & Languages Workshop on Literary Translation 12 Corporate and Industry Relations (CIR) Inauguration of Academic Activities and 16th Vidyamritam Series Inauguration of Academic Activities for 2018, 16th annual series Kochi presided over the function. Prof. Sunanda Muraleedharan, of Vidyamritam extramural lectures and the Corporate Social Chairperson, Amrita School of Business, Kochi offered felicitations. Responsibility (CSR) initiatives for 2018 were conducted on 16th Best Student and Staff Library Users and Staff and students who July. After an enchanting welcome dance by the students, Swami did vacation internships in AIMS Hospital and our campus were Purnamritananda Puri, General Secretary, Mata Amritanandamayi honoured. Later vegetable and plant saplings were presented to Math blessed the function. The chief guest Sri. A.P.M. Mohammed the parents of the new students of 2018 as a mark of thanks Hanish, IAS, Managing Director, Kochi Metro Rail Ltd. (KMRL) giving and prayer to the Mother nature. -

Sewa News Readers” November 2018

“Diwali wishes to all Sewa News readers” www.sewausa.org November 2018 Sewa Team visits Kerala to Finalize Flood Rehabilitation Plan The devastating southwest monsoon this year left the entire state of Kerala inundated leaving 221 collapsed bridges, nearly 6,250 miles of damaged roads, and it destroyed more than 42,000 hectares of crops that affected 260,000 farmers. Over a million people were displaced, and 370 people died in the floods. Sewa International President Dr. Sree Sreenath, together with two Sewa mission-oriented staff -- Saravanan Dakshinamoorthy and Aravinda Rajagopal -- visited Kerala on October 9 and 10 to discuss and finalize the Kerala Floods Rehabilitation Program for which Sewa has raised $375,000. Contd. on Page 2 Executive’s Corner Dear Sewa Supporter, I would like to share about some of the philosophical emotional. Additionally, the Bhagavad Gita advises that a aspects of Sewa, in three parts: Sādhanā (reverent true sādhak on the path of karma yoga should work with practice), Sādhak (the aspirant), and Sādhya (achievable a degree of detachment. goal). Sādhya is the ultimate achievable goal. Sewa sādhya is Sādhanā is practice undertaken in the pursuit of a to create a social order based on three principles: “Let all goal. Sewa sādhanā is to elevate one’s attitude from be happy” (Sarve bhavantu sukhinah); the “World is one self-interest to self-realization by serving others. The family” (Vasudhaiva kutumbakam); and a “Strifeless global attitude of ‘helping others’ comes from self-interest due society” (Jagat shanthi). to compassion, pity, desire for popularity, selfish gain, or some ulterior motive, whereas the attitude of ‘serving Sewa International is an organization with a mission to others’ comes from a total surrender to divinity, and achieve this sādhya by creating selfless workers (“Service the realization that we are but an instrument by divine above self”), with a bond of ideology (Hindu faith-based), design to render service on behalf of the divine. -

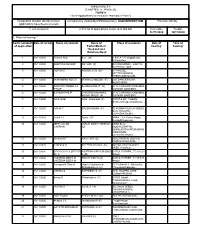

Accused Persons Arrested in Thiruvananthapuram City District from 07.06.2020To 13.06.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Thiruvananthapuram City district from 07.06.2020to 13.06.2020 Name of Name of Name of the Place at Date & Arresting the Court Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, at which No. Accused Sex Sec of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 TC 41/2426,Min House,Toll Gate Junction,Kalippankula Muhammed 39/Mal 13-06- 1166/2020/27 VIMAL SI of 1 Maheen m ward,Manacaud FORT FORT STATION BAIL Fizal e 2020/ 9 IPC Police Village, KERALA, THIRUVANANTHAPUR AM CITY, FORT TC39/884,Cheruvalli Lane, Near Punartham,Auditoria m, 42/Mal 13-06- 1167/2020/27 VIMAL SI of 2 Adithyakiran.P Pavithrakumar Kanjirampara.P.O,Vatt FORT FORT STATION BAIL e 2020/ 9 IPC Police iyoorkavau Village, KERALA, THIRUVANANTHAPUR AM CITY, TC 5/1068,DNRA 72, Kadavil Veedu,Devi Nagar, Peroorkada 41/Mal 13-06- 1168/2020/27 VIMAL SI of 3 Nivin James Ward,Kudappanakkun FORT FORT STATION BAIL e 2020/ 9 IPC Police nu Village, KERALA, THIRUVANANTHAPUR AM CITY, TC 23/1402, BIJU BHAVAN, NEAR 23/Mal 07-06- 677/2020/279 4 Sarath.S Sasi.C POPULAR SERVICE Melarannoor KARAMANA Sivakumar V.R STATION BAIL e 2020/18:23 IPC STATION, MELARANOOR TC 50/490, Marwel A3, 21/Mal Maruthoorkada 08-06- 679/2020/279 5 Aswin.V Vikraman.R Vadakkamneelam, KARAMANA Sivakumar V.R STATION BAIL e vu 2020/20:06 IPC Maruthoorkadavu, Kalady, 8921964885 TC 52/716, 682/2020/279 25/Mal Panakkalvilakam, 10-06- 6 Sarath.M Manoharan.C Chullamukku IPC & 185 MV KARAMANA Sivakumar V.R STATION BAIL e Poozhikunnu, Estate 2020/08:41 ACT P.O TC 64/1097, Ananthu Ananthu 23/Mal 10-06- 683/2020/279 7 Anil Kumar Nivas, Karumam, Karamana KARAMANA Sivakumar V.R STATION BAIL Krishnan A e 2020/12:36 IPC Melamcode ward Gollangi Chinnarao House, Nr. -

Marketing of Malayalam Films Through New Media

MARKETING OF MALAYALAM FILMS THROUGH NEW MEDIA ANMI ELIZABETH SABU Registered Number: 1424024 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Media and Communication Studies CHRIST UNIVERSITY Bengaluru 2016 Program Authorized to Offer Degree Department of Media Studies ii CHRIST UNIVERSITY Department of Media Studies This is to certify that I have examined this copy of a master’s thesis by Anmi Elizabeth Sabu Registered Number: 1424024 and have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Committee Members: _____________________________________________________ [CHANDRASEKHAR VALLATH] _____________________________________________________ Date: __________________________________ iii iv I, Anmi Elizabeth Sabu, confirm that this dissertation and the work presented in it are original. 1. Where I have consulted the published work of others this is always clearly attributed. 2. Where I have quoted from the work of others the source is always given. With the exception of such quotations this dissertation is entirely my own work. 3. I have acknowledged all main sources of help. 4. If my research follows on from previous work or is part of a larger collaborative research project I have made clear exactly what was done by others and what I have contributed myself. 5. I am aware and accept the penalties associated with plagiarism. Date: v vi CHRIST UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT Marketing of Malayalam Films through New Media Anmi Elizabeth Sabu The research studies the marketing strategies used by Malayalam films through New Media. In this research new media includes Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Whatsapp and instagram. -

Media in Kerala

MEDIA IN KERALA THIRUVANANTHAPURAM MEDIA IN KERALA THIRUVANANTHAPURAM Print Media STD CODE: 0471 Chandrika .................................... 3018392, ‘93, ‘94, 3070100,101,102 Kosalam, TC -25/2029(1) Dharmalayam Road, Thampanoor, Thiruvananthapuram. Fax ................................................................................... 2330694 Email ................................................... [email protected] Shri. C V. Sreejith (Bureau Chief) .............................. 9895842919 Shri. K.Anas (Reporter) ............................................. 9447500569 Shri. Sinu .S.P.Kurup (Reporter) ............................ 0472-2857157 Shri. Firdous Thaha (Reporter) .................................. 9895643595 Shri. K.R.Rakesh (Reporter) ...................................... 9744021782 Shri. Jitha Kanakambaran (Reporter) ......................... 9447765483 Shri. Arun P Sudhakaran (Sub-editor) ........................ 9745827659 Shri. K Sasi (Chief Photographer) .............................. 9446441416 Daily Thanthi ........................................................................... 2320042 T.C.42/824/4,Anandsai bldg.,2nd floor,thycaud ,Tvm-14 Email ......................................................... [email protected] Shri.S.Jesu Denison(Staff Reporter) ............................ 9847424238 Deccan Chronicle .......................................................... 2735105, 06, 07 St. Joseph Press Building, Cotton Hills, Thycaud P.O., Thiruvananthapuram -14 Email .......................................................... -

Accused Persons Arrested in Ernakulam City District from 21.06.2020To27.06.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Ernakulam City district from 21.06.2020to27.06.2020 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Cr no 334/20, Age Thattekattil House, U/s188, 269 Aneeshkum Asokkumar IPC & 118 e Kp Benoy K G 1 36/20 Seethathode PO, Brahmapuram 21.06.20 Infopark Station Bail ar , Act ,4 (2) (j) r/w SI of Police , Male Ranni, Pathanamthitta 5 of KEDO 2020 Age Cr No 335/20, Vanikattu House, A1- Mariya 22/20 Prakkamughal, U/s, 385, 388, Shaju A N JFCM 2 Baiju, Vezhaparambu, 22.06.20 Infopark Paul, , Fe Kakkanad 389, 506 & 34 SI of Police Kakkanad Mulanthuruthy Male IPC Age Cr No 335/20, A2- Elisa W/o Nafa 24/20 Vanikattu House, Prakkamughal, U/s, 385, 388, Shaju A N JFCM 3 22.06.20 Infopark Nafa, Davis, , Fe Vezhaparambu, Kakkanad 389, 506 & 34 SI of Police Kakkanad Male Mulanthuruthy IPC Cr No 338/20, Thyvalappil House, Age U/s 188, 269 Vijayakumar M A1- Deepak Chandraha Nenmini, Thykad IPC & 118 e Kp 4 23/20 Rajagiri Jn 24.06.20 Infopark H Station Bail Raj T C, san, Village, Guruvayoor, Act ,4 (2) (a,e) , Male r/w 5 of KEDO SI of Police 2020 Ambalathuveettil Cr No 338/20, A2- Age House, U/s 188, 269 Vijayakumar M IPC & 118 e Kp 5 Muhammed Noushad, 23/20 Panikkanmoola, Rajagiri Jn 24.06.20 Infopark H Station Bail Act ,4 (2) (a,e) Nihas, , Male Kattoor Village, r/w 5 of KEDO SI of Police Thrissur -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2009-11. 2009 [Price: Rs. 20.00 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 11] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, MARCH 25, 2009 Panguni 12, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2040 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Pages Change of Names .. .. 385-432 Notices .. .. 433 NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES My son, D. Arun, son of Thiru P. Dharmaraj, born on I, M. Santhosh, son of Thiru K. Mohanan Nair, born on 8th January 2008 (native district: Coimbatore), residing at 1st June 1977 (native district: Kollam—Kerala), residing at Old No. 7, New No. 7-A, S.N.D. Layout, Tatabad, Power No. 681, S.T. Shead Road, Gandhi Nagar, Sathyamangalam, House, Coimbatore-641 012, shall henceforth be known as Erode-638 402, shall henceforth be known D.S. THARUNKRISHNA. as M. SANTTHOSH. K. SUGANTHA. M. SANTHOSH. Coimbatore, 16th March 2009. (Mother.) Sathyamangalam, 16th March 2009. Thirumathi, A. Kalaivani, (Hindu), wife of Thiru I, R. Shanthi Krishna, wife of Thiru M. Santhosh, born on B. Ragamathullah, born on 18th June 1985 (native district: 13th April 1983 (native district: Idukki—Kerala), residing at Erode), residing at No. 249-K, Pandian Nagar, No. 681, S.T. Shead Road, Gandhi Nagar, Sathyamangalam, Vadugapalayampudur, Modachur Village, Gobichettipalayam Erode-638 402, shall henceforth be known Taluk, Erode-638 476, has converted to Islam with the name of R. -

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications For

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): KAZHAKKOOTTAM Revision identity applications have been received) 1. List number@ 2. Period of applications (covered in this list) From date To date 16/11/2020 16/11/2020 3. Place of hearing * Serial number$ Date of receipt Name of claimant Name of Place of residence Date of Time of of application Father/Mother/ hearing* hearing* Husband and (Relationship)# 1 16/11/2020 Richa B Arun Ben (M) K B R A 175, Elippakuzhy, Kazhakutom, ., , 2 16/11/2020 SABEENA ASHRAF ASHRAF (F) SHIJINA MANZIL, KARIYIL, KAZHAKUTTOM, , 3 16/11/2020 GOPAN A KOUSALYA B (M) G P HOUSE, NETTAYAKONAM, THEKKUMBHAGAM, , 4 16/11/2020 MUHAMMAD ADIL S M SAINULABDEEN (F) 129, DARUSSALAM, ALENCHERY, , 5 16/11/2020 ASWATHY REBECCA SURESH PHILIP (H) 2410, CHAVANICKAMANNIL, PHILIP COTMAN GARDENS, , 6 16/11/2020 SURESH PHILIP CHAVANICKAMANNIL 2410, CHAVANICKAMANNIL, KOSHY PHILIP (F) COTMAN GARDENS, , 7 16/11/2020 Ashik Nizar Nizar Ahammad (F) 2/3157-6 Alif, Thadathil Brothers Road, Chanthavila, ., , 8 16/11/2020 NISHA C SREENIVASAN (F) 12 KUNNATHUVILA VEEDU, SANTHIPURAM, ULIYAZHATHURA, , 9 16/11/2020 Gokul S J Syam J (F) VNRA - 5.A Vishnu Nagar, Keraladithyapuram, ., , 10 16/11/2020 JEFRI JACOB JUSLIN MARY CHERIAN KERA B-12, CHERIAN (O) MODIYUZHATHIL, KERALADITHYAPURAM,PO WDIKONAM, ULIYAZHATHURA, , 11 16/11/2020 Shekhar M RAJITHA K (O) 1202, KRISTAL ONYX-D, THRIPPADAPURAM, ., , 12 16/11/2020 ARSHA S R SHEEBARANI -

The Artifice of Brahmin Masculinity in South Indian Dance

Luminos is the Open Access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and reinvigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org The publisher and the University of California Press Foundation gratefully acknowledge the generous support of the Ahmanson Foundation Endowment Fund in Humanities. Impersonations Impersonations The Artifice of Brahmin Masculinity in South Indian Dance Harshita Mruthinti Kamath UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advanc- ing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Oakland, California © 2019 by Harshita Mruthinti Kamath This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses. Suggested citation: Kamath, H. M. Impersonations: The Artifice of Brahmin Masculinity in South Indian Dance. Oakland: University of California Press, 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1525/luminos.72 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kamath, Harshita Mruthinti, 1982- author. Title: Impersonations : the artifice of Brahmin masculinity in South Indian dance / Harshita Mruthinti Kamath. Description: Oakland, California : University of California Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Mapping Dalit Feminism Towards an Intersectional Standpoint

Mapping Dalit Feminism Towards an Intersectional Standpoint ANANDITA PAN Foreword by J. Devika Copyright © Anandita Pan, 2021 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. First published in 2021 by SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd STREE B1/I-1 Mohan Cooperative Industrial Area 16 Southern Avenue Mathura Road, New Delhi 110 044, India Kolkata 700 026 www.sagepub.in www.stree-samyabooks.com SAGE Publications Inc 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, California 91320, USA SAGE Publications Ltd 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP, United Kingdom SAGE Publications Asia-Pacific Pte Ltd 18 Cross Street #10-10/11/12 China Square Central Singapore 048423 Published by Vivek Mehra for SAGE Publications India Pvt. Ltd. Typeset in 11/14 pt Goudy Old Style by Fidus Design Pvt. Ltd, Chandigarh. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020945415 ISBN: 978-93-81345-55-9 (HB) SAGE Stree team: Aritra Paul, Amrita Dutta and Ankit Verma To Ma and Baba. Thank you for choosing a SAGE product! If you have any comment, observation or feedback, I would like to personally hear from you. Please write to me at [email protected] Vivek Mehra, Managing Director and CEO, SAGE India. Bulk Sales SAGE India offers special discounts for purchase of books in bulk. We also make available special imprints and excerpts from our books on demand. For orders and enquiries, write to us at Marketing Department SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd B1/I-1, Mohan Cooperative Industrial Area Mathura Road, Post Bag 7 New Delhi 110044, India E-mail us at [email protected] Subscribe to our mailing list Write to [email protected] This book is also available as an e-book. -

Department of Architecture, Cet Alumini List

DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE, CET ALUMINI LIST Dear Alumni/ Visitor, while all care has been given in updating the list, we know it is not complete nor up to date. If you can contribute in anyway towards updating any entries below, even if its just an updated mobile number, please email to [email protected] anyone wants to change your personal number to office/ residence number, or omit the number altogether, please email us. Thank you in advance. 1964 – 1969 Batch. (joined from 3rd Year B. Tech.) Sl. Name Contact No. Address Email No. AMANULLA KHAN. 1 K 9846762025 N M Salim Associates, Kozhikkode Valiyaveetil, Industrial Estate Road, Near Municipal office, 2 JACOB JHON 9995287808 Changampuzha Nager P O, Cochin 33. [email protected] KASTHURI 3 RANGAN A 8547141019 Sarovaram, Sreepuram Road, Poojappura, Tvm 695012 [email protected] 4 NAMBOOTHIRI (Late) 1964-69 2nd Batch (joined from 2nd Year B. Tech.) 1 B. PRABHAKARAN 2 B. S. BHOOSHAN 9845106500 48 c, 4th Block, 1st cross, Jayalakshmipuram, Mysore 12 [email protected] 3 BABU MATHEW 94467 00098 T.C.2/3490, Building Lanes, Chalakuzhi Junction, Pattom P.O., [email protected] 4 CONSTANT. K. G Thiruvananthapuram 695 004 Jose & JJ Architects, Trade Archade Building, Opp. YMCA, [email protected] 5 JOSEPH PHILIP 9447276333 Kannoor Road, Calicut 673001. 6 MADHAVAN.S 7 MANI GEORGE 8 MOHANAN.P RK.Ramesh Architects,8/384,Corporation Office Road,Calicut 9 R.K.RAMESAN 9847001110 673032 [email protected] RAVINDRANATHAN TC-15/2006, VRA-A-16, Sree Bhavanam, Womens College 10 NAIR 9447778285 Lane,Vazhuthacaud, Tvm 695014 [email protected] 11 SASIDHARAN.M.K Chandran & Associates, Krishnaprabha, A-122, Kanakanagar, 12 T.