Administration of Barack Obama, 2014 Remarks at the University Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

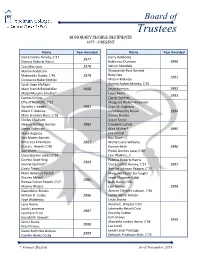

Honorary Degree Recipients 1977 – Present

Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Claire Collins Harvey, C‘37 Harry Belafonte 1977 Patricia Roberts Harris Katherine Dunham 1990 Toni Morrison 1978 Nelson Mandela Marian Anderson Marguerite Ross Barnett Ruby Dee Mattiwilda Dobbs, C‘46 1979 1991 Constance Baker Motley Miriam Makeba Sarah Sage McAlpin Audrey Forbes Manley, C‘55 Mary French Rockefeller 1980 Jesse Norman 1992 Mabel Murphy Smythe* Louis Rawls 1993 Cardiss Collins Oprah Winfrey Effie O’Neal Ellis, C‘33 Margaret Walker Alexander Dorothy I. Height 1981 Oran W. Eagleson Albert E. Manley Carol Moseley Braun 1994 Mary Brookins Ross, C‘28 Donna Shalala Shirley Chisholm Susan Taylor Eleanor Holmes Norton 1982 Elizabeth Catlett James Robinson Alice Walker* 1995 Maya Angelou Elie Wiesel Etta Moten Barnett Rita Dove Anne Cox Chambers 1983 Myrlie Evers-Williams Grace L. Hewell, C‘40 Damon Keith 1996 Sam Nunn Pinkie Gordon Lane, C‘49 Clara Stanton Jones, C‘34 Levi Watkins, Jr. Coretta Scott King Patricia Roberts Harris 1984 Jeanne Spurlock* Claire Collins Harvey, C’37 1997 Cicely Tyson Bernice Johnson Reagan, C‘70 Mary Hatwood Futrell Margaret Taylor Burroughs Charles Merrill Jewel Plummer Cobb 1985 Romae Turner Powell, C‘47 Ruth Davis, C‘66 Maxine Waters Lani Guinier 1998 Gwendolyn Brooks Alexine Clement Jackson, C‘56 William H. Cosby 1986 Jackie Joyner Kersee Faye Wattleton Louis Stokes Lena Horne Aurelia E. Brazeal, C‘65 Jacob Lawrence Johnnetta Betsch Cole 1987 Leontyne Price Dorothy Cotton Earl Graves Donald M. Stewart 1999 Selma Burke Marcelite Jordan Harris, C‘64 1988 Pearl Primus Lee Lorch Dame Ruth Nita Barrow Jewel Limar Prestage 1989 Camille Hanks Cosby Deborah Prothrow-Stith, C‘75 * Former Student As of November 2019 Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Max Cleland Herschelle Sullivan Challenor, C’61 Maxine D. -

The Nobel Peace Prize

TITLE: Learning From Peace Makers OVERVIEW: Students examine The Dalai Lama as a Nobel Laureate and compare / contrast his contributions to the world with the contributions of other Nobel Laureates. SUBJECT AREA / GRADE LEVEL: Civics and Government 7 / 12 STATE CONTENT STANDARDS / BENCHMARKS: -Identify, research, and clarify an event, issue, problem or phenomenon of significance to society. -Gather, use, and evaluate researched information to support analysis and conclusions. OBJECTIVES: The student will demonstrate the ability to... -know and understand The Dalai Lama as an advocate for peace. -research and report the contributions of others who are recognized as advocates for peace, such as those attending the Peace Conference in Portland: Aldolfo Perez Esquivel, Robert Musil, William Schulz, Betty Williams, and Helen Caldicott. -compare and contrast the contributions of several Nobel Laureates with The Dalai Lama. MATERIALS: -Copies of biographical statements of The Dalai Lama. -List of Nobel Peace Prize winners. -Copy of The Dalai Lama's acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize. -Bulletin board for display. PRESENTATION STEPS: 1) Students read one of the brief biographies of The Dalai Lama, including his Five Point Plan for Peace in Tibet, and his acceptance speech for receiving the Nobel Prize for Peace. 2) Follow with a class discussion regarding the biography and / or the text of the acceptance speech. 3) Distribute and examine the list of Nobel Peace Prize winners. 4) Individually, or in cooperative groups, select one of the Nobel Laureates (give special consideration to those coming to the Portland Peace Conference). Research and prepare to report to the class who the person was and why he / she / they won the Nobel Prize. -

Let My People Go! Kenneth Lasson University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected]

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 4-22-2011 Let My People Go! Kenneth Lasson University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the International Law Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, and the National Security Law Commons Recommended Citation Let My People Go!, Baltimore Jewish Times, April 22, 2011 This Editorial is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BALTIMORE JEWISH TIMES {Op-Ed} April 22, 2011 LET MY PEOPLE GO! Kenneth Lasson As we continue celebrating the season of freedom - perhaps the most symbolic of all Jewish holidays, for Passover above all contemplates the meaning of redemption, liberation from the shackles of bondage - we should not forget that two of our people remain locked away from their families and the world. We know one is alive but barely surviving the harsh conditions of imprisonment. The other may be neither alive nor well. For Jonathan J. Pollard, the American serving a life sentence for disclosing classified information to Israel, each Passover is a poignant reminder of the 25 years he has already been confined to a federal penitentiary. He suffers from a variety of ailments, at least one of which recently threatened his life. -

Happenings Around Town

happenings around town Tuesdays, July 13th- August 26th, 7:30pm- "Do July 9th and beyond you have a high school daughter who is around for any part of the summer? Have her Sunday, July 11th, 8:45am– Join Beth Aaron’s Shivti join us on Tuesday nights for NCSY'S Summer learning program as we continue learning issues Girls Learning Initiative. SGLI is an opportunity around conducting business on Shabbat. Included in for high school girls who are home for the this topic is the contemporary issue addressed by summer to spend time with other girls their age today's poskim regarding web-based businesses which and have some exciting Torah learning are "open" 24/7, including eBay and Amazon. Join at experiences. Classes will be offered by dynamic https://zoom.us/j/91366375195? presenters from our local Yeshivot. SGLI is pwd=d3NacnA2SVdLbDJQZjNoSnlaaHhzUT09 sponsored by NCSY and supported by Bruriah, Zoom meeting ID: 913 6637 5195. Passcode: 888717. Maayanot, Naaleh and Yeshivat Frisch. The For additional program details, contact Mordy Ungar sessions will be at Congregation Beth Abraham, at [email protected]. 396 New Bridge Rd, Bergenfield in the social hall. Yummy food will be served! For more Sunday, July 11th, 9am– 7pm- Please drop off gently information please contact Dr. Aliza Frohlich at used children’s clothing at the Keter Torah ballroom. [email protected]. Volunteers needed as well to sort clothing! Older kids and teens welcome! For more info about donating and Sunday, July 18th, 3:15pm- The Northern New volunteering and/or to inquire about shopping for Jersey Holocaust Memorial & Education Center your children at the drive next week, please contact & Congregation Keter Torah invite you to A [email protected]. -

Our Government Unites to Honor His Holiness the Dalai Lama Our

INSIDE: Open Letter to Nancy Pelosi Photo Essay: His Holiness Accepts the Congressional Gold Medal Tibet in the News New Report: The Trans-Tibetan Railroad WINTER 2008 A publication of the TibetPRESS WATCH International Campaign for Tibet Our Government Unites to Honor His Holiness the Dalai Lama MANDALA SOCIETY YOUR LIVING LEGACY TO TIBET The Mandala Society is an intimate group of Tibet supporters, committed to helping future generations of Tibetans. By including the International Campaign for Tibet in their will or trust, Mandala Society members ensure that ICT will continue to have the resources to promote a peaceful resolution of the occupation of Tibet, and will be able to help rebuild Tibet when Tibetans achieve genuine autonomy. For more information about Mandala Society member - ship, please contact Melissa Winchester at 202-785-1515, ext. 225, [email protected], or use the envelope attached to this newsletter to request a call. The Mandala Society of the International Campaign for Tibet 2 Whenever world leaders, governments and parliamentarians convey strong solidarity with the Tibetan people, it contributes immensely to peace, nonviolence and stability. TIBET PRESSWATCH From Lodi Gyari The International Campaign for Tibet As we come to an end of one of the most successful years works to promote human rights and democratic freedoms for for Tibet and begin to prepare to face the challenges of the people of Tibet. the coming year, I want to personally thank you for your Founded in 1988, ICT is a non-profit support and also appeal for your continuous solidarity membership organization with offices with the people of Tibet. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2012 Remarks on Presenting The

Administration of Barack Obama, 2012 Remarks on Presenting the Presidential Medal of Freedom to President Shimon Peres of Israel June 13, 2012 Good evening, everybody. Please have a seat. On behalf of Michelle and myself, welcome to the White House on this beautiful summer evening. The United States is fortunate to have many allies and partners around the world. Of course, one of our strongest allies, and one of our closest friends, is the State of Israel. And no individual has done so much over so many years to build our alliance and to bring our two nations closer as the leader that we honor tonight, our friend Shimon Peres. Among many special guests this evening we are especially grateful for the presence of Shimon's children—Zvia, Yoni, and Chemi—and their families. Please rise so we can give you a big round of applause. We have here someone representing a family that has given so much for peace, a voice for peace that carries on with the legacy of her father Yitzhak Rabin, and that's Dalia. We are grateful to have you here. Leaders who've helped ensure that the United States is a partner for peace—and in particular, I'm so pleased to see Secretary Madeleine Albright, who is here this evening; and one of the great moral voices of our time and an inspiration to us all, Professor Elie Wiesel. The man, the life that we honor tonight is nothing short of extraordinary. Shimon took on his first assignment in Ben-Gurion's Haganah, during the struggle for Israeli independence in 1947, when he was still in his early twenties. -

GPA Summer Reading for Incoming 9Th Grade

GPA Summer Reading for Incoming 9th Grade Welcome to Great Path Academy! In preparation for the 2018-2019 school year, we require that incoming ninth grade students read a selection of texts. This purpose of this assignment is to provide students with engaging texts that explore the themes of integrity, perseverance, and identity as they relate to issues in the 21st century. Once school begins, students will further develop their understanding of the texts in an extended project of their choosing. Students are required to read all three texts; however, they must only complete the accompanying questions and responses for two out of the three texts. Text Options: John Donne “No Man is an Island” Elie Wiesel Nobel Peace Prize Acceptance Speech Malala Yousafzai: A Normal yet Powerful Girl Name: Class: No Man Is An Island By John Donne 1624 John Donne (1572-1631) was an English poet whose time spent as a cleric in the Church of England often influenced the subjects of his poetry. In 1623, Donne suffered a nearly fatal illness, which inspired him to write a book of meditations on pain, health, and sickness called Devotions upon Emergent Occasions. “No Man is an Island” is a famous section of “Meditation XVII” from this book. As you read, take notes on how the author uses figurative language to describe humanity. Modern Version [1] No man is an island entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main; if a clod1 be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory2 were, as [5] well as any manner of thy friends or of thine own were; any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind. -

About the Elie Wiesel Center for Jewish Studies

Table of Contents About the Elie Wiesel Center for Jewish Studies...........................................................3 Faculty......................................................................................................................................4 2017-18 Courses....................................................................................................................5 Director’s Message...............................................................................................................6 Futures: The Elie Wiesel Center Memorial Lectures.....................................................8 People Faculty Accolades......................................................................................................10 Visiting Faculty in Israel Studies.............................................................................14 A Warm Farewell to Dr. Alexandra Herzog..........................................................14 The Postdoctoral Associate Program....................................................................15 Alumni Spotlight: Rachel Kohl Finegold................................................................16 Student Support.........................................................................................................17 Undergraduate Staff Social Action........................................................................18 Graduate Student Spotlight: Ellie Ash..................................................................19 2017-18 Graduates...................................................................................................20 -

THEMATIC UNITS and Ever-Growing Digital Library Listing GRADES 9–12 THEMATIC UNITS

THEMATIC UNITS and Ever-Growing Digital Library Listing GRADES 9–12 THEMATIC UNITS GRADE 9 AUTHOR GENRE StudySync®TV UNIT 1 | Divided We Fall: Why do we feel the need to belong? Writing Focus: Narrative Marigolds (SyncStart) Eugenia Collier Fiction The Necklace Guy de Maupassant Fiction Friday Night Lights H.G. Bissinger Informational Text Braving the Wilderness: The Quest for True Belonging and the Courage to Stand Alone Brene Brown Informational Text Why I Lied to Everyone in High School About Knowing Karate Jabeen Akhtar Informational Text St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves Karen Russell Fiction Sure You Can Ask Me a Personal Question Diane Burns Poetry Angela’s Ashes: A Memoir Frank McCourt Informational Text Welcome to America Sara Abou Rashed Poetry I Have a Dream Martin Luther King, Jr. Argumentative Text The Future in My Arms Edwidge Danticat Informational Text UNIT 2 | The Call to Adventure: What will you learn on your journey? Writing Focus: Informational Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening Robert Frost Poetry 12 (from ‘Gitanjali’) Rabindranath Tagore Poetry The Journey Mary Oliver Poetry Leon Bridges On Overcoming Childhood Isolation and Finding His Voice: ‘You Can’t Teach Soul’ Jeff Weiss Informational Text Highest Duty: My Search for What Really Matters Chesley Sullenberger Informational Text Bessie Coleman: Woman Who ‘dared to dream’ Made Aviation History U.S. Airforce Informational Text Volar Judith Ortiz Cofer Fiction Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail Cheryl Strayed Informational Text The Art -

SCSL Press Clippings

SPECIAL COURT FOR SIERRA LEONE OUTREACH AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS OFFICE PRESS CLIPPINGS Enclosed are clippings of local and international press on the Special Court and related issues obtained by the Outreach and Public Affairs Office as at: Monday, 23 March 2009 Press clips are produced Monday through Friday. Any omission, comment or suggestion, please contact Martin Royston-Wright Ext 7217 2 Local News Liberians Transit Guns to Gola Forest in Sierra Leone / Awoko Page 3 The Present Situation of Juvenile Justice in Sierra Leone / Independent Observer Page 4 Prison Watch Damns Justice Patrick Hamilton / For di People Page 5 Rwanda Signs Prisoner Deal with Sierra Leone Court / Standard Times Page 6 Africa’s Evil: An Examination....Is There More or Less Evil in Africa Today? / Standard Times Pages 7-13 International News Taylor, Woewiyu to Testify in April… / The Independent (Liberia) Pages 14-15 “ I Will Not Bow to Pressure” / The Inquirer (Liberia) Page 16 Griffiths Faux Pass and Misdirected Appeal / The Daily Observer (Liberia) Page 17 Charles Taylor…/ New Democrat (Liberia) Page 18 UNMIL Public Information Office Complete Media Summaries / UNMIL Pages 19-20 War Crimes Court Might Never Arrest Al-Bashir / The Standard Pages 21-24 ISS Conference Tackles Impact of ICC Arrest Warrants / Voice of America Page 25 3 Awoko Monday, 23 March 2009 4 Independent Observer Monday, 23 March 2009 5 For di People Monday, 23 March 2009 Prison Watch Damns Justice Patrick Hamilton 6 Standard Times Sunday, 22 March 2009 Rwanda Signs Prisoner Deal with Sierra Leone Court Up to eight people sentenced by Sierra Leone's war crimes court can serve their sentences in a new Rwandan prison under a deal with Kigali, the court said Friday. -

'Night' by Elie Wiesel

A TEACHER’S RESOURCE for PART OF THE “WITNESSES TO HISTORY” SERIES PRODUCED BY FACING HISTORY AND OURSELVES & VOICES OF LOVE AND FREEDOM A TEACHER’S RESOURCE for Night by Elie Wiesel Part of the “Witnesses to History” series produced by Facing History and Ourselves & Voices of Love and Freedom Acknowledgments Voices of Love and Freedom (VLF) is a nonprofit educational organization that pro- motes literacy, values, and prevention. VLF teacher resources are designed to help students: • appreciate literature from around the world • develop their own voices as they learn to read and write • learn to use the values of love and freedom to guide their lives • and live healthy lives free of substance abuse and violence. Voices of Love and Freedom was founded in 1992 and is a collaboration of the Judge Baker Children’s Center, Harvard Graduate School of Education, City University of New York Graduate School, and Wheelock College. For more information, call 617-635-6433, fax 617-635-6422, e-mail [email protected], or write Voices of Love and Freedom, 67 Alleghany St., Boston, MA 02120. Facing History and Ourselves National Foundation, Inc. (FHAO) is a national educa- tional and teacher training organization whose mission is to engage students of diverse backgrounds in an examination of racism, prejudice, and antisemitism in order to promote the development of a more humane and informed citizenry. By studying the historical development and lessons of the Holocaust and other exam- ples of genocide, students make the essential connection between history and the moral choices they confront in their own lives. -

RWBA's Holocaust, Genocide and Human Rights Programme

RWBA’s Holocaust, genocide and human rights programme “For the dead and the living, we must bear witness.” – Elie Wiesel “Genocide is the responsibility of the entire world.” - Ann Clwyd To mark #Genocide71, to raise awareness and encourage prevention opportunities in our school, community and wider society we are to host a series of events (Dec 9-13) as part of our Holocaust, genocide and human rights programme (HGP). On the 9th December we will be holding a ‘Time to Talk about Genocide’ workshop day for 35 of our RWBA6 and PE department students. We will use the lens of the power of sport, and the testimony of Eric Murangwa to reflect upon the stages of genocide and the case study of the genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda. So we thank Mr I’Anson for his support and engagement in making this opportunity possible. Genocide is disturbing, complex and personal-encountering it is hard and yet it draws upon active global citizenships and demands we each look at ourselves and how we can contribute to a world where genocide might, one day, be history. We know from previous such days, how meaningful and enriching to our whole school programme and curriculum offer such experiences and opportunities are. There are always so many insightful contributions, thoughtful questions and powerful learning discussions. It’s clear from the RAG rating table at the start and end of such day’s that students’ substantive knowledge improves as a result. For example, they now know who Carl Wilkens is, who coined the term ‘genocide’ and can explain what Jan Karski did and how he was treated in America.