(In)Carceral Imagination by Solomon S. Hayes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Baldwin As a Writer of Short Fiction: an Evaluation

JAMES BALDWIN AS A WRITER OF SHORT FICTION: AN EVALUATION dayton G. Holloway A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 1975 618208 ii Abstract Well known as a brilliant essayist and gifted novelist, James Baldwin has received little critical attention as short story writer. This dissertation analyzes his short fiction, concentrating on character, theme and technique, with some attention to biographical parallels. The first three chapters establish a background for the analysis and criticism sections. Chapter 1 provides a biographi cal sketch and places each story in relation to Baldwin's novels, plays and essays. Chapter 2 summarizes the author's theory of fiction and presents his image of the creative writer. Chapter 3 surveys critical opinions to determine Baldwin's reputation as an artist. The survey concludes that the author is a superior essayist, but is uneven as a creator of imaginative literature. Critics, in general, have not judged Baldwin's fiction by his own aesthetic criteria. The next three chapters provide a close thematic analysis of Baldwin's short stories. Chapter 4 discusses "The Rockpile," "The Outing," "Roy's Wound," and "The Death of the Prophet," a Bi 1 dungsroman about the tension and ambivalence between a black minister-father and his sons. In contrast, Chapter 5 treats the theme of affection between white fathers and sons and their ambivalence toward social outcasts—the white homosexual and black demonstrator—in "The Man Child" and "Going to Meet the Man." Chapter 6 explores the theme of escape from the black community and the conseauences of estrangement and identity crises in "Previous Condition," "Sonny's Blues," "Come Out the Wilderness" and "This Morning, This Evening, So Soon." The last chapter attempts to apply Baldwin's aesthetic principles to his short fiction. -

The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Libraries Dublin Gate Theatre Archive The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979 History: The Dublin Gate Theatre was founded by Hilton Edwards (1903-1982) and Micheál MacLiammóir (1899-1978), two Englishmen who had met touring in Ireland with Anew McMaster's acting company. Edwards was a singer and established Shakespearian actor, and MacLiammóir, actually born Alfred Michael Willmore, had been a noted child actor, then a graphic artist, student of Gaelic, and enthusiast of Celtic culture. Taking their company’s name from Peter Godfrey’s Gate Theatre Studio in London, the young actors' goal was to produce and re-interpret world drama in Dublin, classic and contemporary, providing a new kind of theatre in addition to the established Abbey and its purely Irish plays. Beginning in 1928 in the Peacock Theatre for two seasons, and then in the theatre of the eighteenth century Rotunda Buildings, the two founders, with Edwards as actor, producer and lighting expert, and MacLiammóir as star, costume and scenery designer, along with their supporting board of directors, gave Dublin, and other cities when touring, a long and eclectic list of plays. The Dublin Gate Theatre produced, with their imaginative and innovative style, over 400 different works from Sophocles, Shakespeare, Congreve, Chekhov, Ibsen, O’Neill, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats and many others. They also introduced plays from younger Irish playwrights such as Denis Johnston, Mary Manning, Maura Laverty, Brian Friel, Fr. Desmond Forristal and Micheál MacLiammóir himself. Until his death early in 1978, the year of the Gate’s 50th Anniversary, MacLiammóir wrote, as well as acted and designed for the Gate, plays, revues and three one-man shows, and translated and adapted those of other authors. -

How Bigger Was Born Anew

Fall 2020 29 ow Bier as Born new datation Reuration and Double Consciousness in Nambi E elle’s Native Son Isaiah Matthew Wooden This essay analyzes Nambi E. Kelley’s stage adaptation of Native Son to consider the ways tt Aicn Aeicn is itlie by n constitte to cts o etion t sharpens particular focus on how Kelley reinvigorates Wright’s novel’s searing social and cil cities by ctiely ein te oisin etpo o oble consciosness n iin ne o, enin, n se to te etpo, elleys Native Son extends the debates about “the problem of the color line” that Du Bois’s writing helped engender at te beinnin o te tentiet centy into te tentyst n, in so oin, opens citicl space to reckon with the persistent and pernicious problem of anti-Black racism. ewords adaptation, refguration, double consciousness, Native Son, Nambi E. Kelley This essay takes as a central point of departure the claim that African American drama is vitalized by and, indeed, constituted through acts of refguration. It is such acts that endow the remarkably capacious genre with any sense or semblance of coherence. Retion is notably a word with multiple signifcations. It calls to mind processes of representation and recalculation. It also points to matters of meaning-making and modifcation. The pref re does important work here, suggesting change, alteration, or even improvement. For the purposes of this essay, I use etion to refer to the strategies, practices, methods, and techniques that African American dramatists deploy to transform or give new meaning to certain ideas, concepts, artifacts, and histories, thereby opening up fresh interpretive and defnitional possibilities and, when appropriate, prompting much-needed reckonings. -

Simply Folk Sing-Along 2018 If I Had a Hammer If I Had a Hammer, I'd Hammer in the Morning, I'd Hammer in the Evening, All Over

Simply Folk Sing-Along 2018 If I Had a Hammer If I had a hammer, I'd hammer in the morning, I'd hammer in the evening, all over this land I'd hammer out danger, I'd hammer out a warning I'd hammer out love between my brothers and my sisters, all over this land If I had a bell, I'd ring it in the morning, I'd ring it in the evening, all over this land I'd ring out danger, I'd ring out a warning I'd ring out love between my brothers and my sisters, all over this land If I had a song, I'd sing it in the morning, I'd sing it in the evening, all over this land I'd sing out danger, I'd sing out a warning I'd sing out love between my brothers and my sisters, all over this land Well I've got a hammer, and I've got a bell, and I've got a song to sing, all over this land It's the hammer of justice, it's the bell of freedom It's the song about love between my brothers and my sisters, all over this land You Are My Sunshine The other night dear as I lay sleeping, I dreamed I held you in my arms, But when I woke dear I was mistaken, and I hung my head and I cried You are my sunshine, my only sunshine, you make me happy when skies are gray, You'll never know dear, how much I love you, please don't take my sunshine away I'll always love you and make you happy, if you will only say the same, But if you leave me and love another, you’ll regret it all someday You told me once dear, you really loved me, and no one could come between, But now you've left me to love another, you have shattered all of my dreams In all my dreams, dear, you seem to leave me; when I awake my poor heart pains So won’t you come back and make me happy, I’ll forgive, dear, I’ll take all the blame City of New Orleans Riding on the City of New Orleans, Illinois Central Monday morning rail Fifteen cars and fifteen restless riders, three conductors and twenty-five sacks of mail. -

Paul Green Foundation

Paul Green Foundation NEWS – October 2017 Native Son’s New Adaptation PAUL GREEN ANNUAL MEETING Playwright Nambi Kelley NOVEMBER 4, 2017 has written plays for NC BOTANICAL GARDEN Steppenwolf, Goodman Theatre and Lincoln Center CHAPEL HILL, NC and most recently was named playwright-in-residence at The 2017 the National Black Theatre in New York. Kelley’s adaptation of Native Son was National Theatre Conference presented to critical acclaim for the premiere December 1-3 in New York City production at the Court Theatre/American Blues Each year the National Theatre Conference Festival. Since that first production it has been Person of the Year names the Paul Green produced in New York, California, Georgia and Award winner. This year’s Person of the Year – Arizona, and published by Samuel French in 2016. Molly Smith selected June Schreiner, a highly The Green Foundation joined with the Wright acclaimed young actor. Since 1989, the Paul Estate to sanction these productions. Green Foundation has honored a “young theatre professional” with this Paul Green Award. A bit of history: Paul Green and Richard Wright’s Native Son that opened on March 24, Founded in 1925, the National Theatre 1941, at the St. James Theatre in New York City, Conference is a not-for-profit organization made was produced by Orson Welles and John up of distinguished members of the American Houseman. Of the very serious disagreement that Theatre Community; Green was instrumental in ensued between Green and Wright, Dr. Laurence the founding the organization and served as Avery, Professor Emeritus, UNC-Chapel Hill president in the early years. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} Citizen Kane Ebook, Epub

CITIZEN KANE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Harlan Lebo | 368 pages | 01 May 2016 | Thomas Dunne Books | 9781250077530 | English | United States Citizen Kane () - IMDb Mankiewicz , who had been writing Mercury radio scripts. One of the long-standing controversies about Citizen Kane has been the authorship of the screenplay. In February Welles supplied Mankiewicz with pages of notes and put him under contract to write the first draft screenplay under the supervision of John Houseman , Welles's former partner in the Mercury Theatre. Welles later explained, "I left him on his own finally, because we'd started to waste too much time haggling. So, after mutual agreements on storyline and character, Mank went off with Houseman and did his version, while I stayed in Hollywood and wrote mine. The industry accused Welles of underplaying Mankiewicz's contribution to the script, but Welles countered the attacks by saying, "At the end, naturally, I was the one making the picture, after all—who had to make the decisions. I used what I wanted of Mank's and, rightly or wrongly, kept what I liked of my own. The terms of the contract stated that Mankiewicz was to receive no credit for his work, as he was hired as a script doctor. Mankiewicz also threatened to go to the Screen Writers Guild and claim full credit for writing the entire script by himself. After lodging a protest with the Screen Writers Guild, Mankiewicz withdrew it, then vacillated. The guild credit form listed Welles first, Mankiewicz second. Welles's assistant Richard Wilson said that the person who circled Mankiewicz's name in pencil, then drew an arrow that put it in first place, was Welles. -

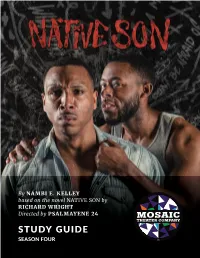

STUDY GUIDE SEASON FOUR Introduction

By NAMBI E. KELLEY based on the novel NATIVE SON by RICHARD WRIGHT Directed by PSALMAYENE 24 STUDY GUIDE SEASON FOUR Introduction “Theatre is a form of knowledge; it should and can also be a means of transforming society. Theatre can help us build our future, rather than just waiting for it.”—Augusto Boal The purpose and goal of Mosaic’s education department is simple. Our program aims to further and cultivate students’ knowledge and passion for theatre and theatre education. We strive for complete and exciting arts engagement for educators, artists, our community, and all learners in the classroom. Mosaic’s education program yearns to be a conduit for open discussion and connection to help students understand how theatre can make a profound impact in their lives, in society, and in their communities. Mosaic Theater Company of DC is thrilled to have your interest and support! Catherine Chmura Arts Education Apprentice—Mosaic Theater Company of DC Written by Catherine Chmura, Khalid Y. Long, and Isaiah M. Wooden 2 NATIVE SON MOSAIC THEATER COMPANY of DC PRESENTS NATIVE SON By Nambi E. Kelley based on the novel NATIVE SON by Richard Wright Directed by Psalmayene 24 Set Designer: Ethan Sinnott Lighting Designer: William K. D’Eugenio Costume Designer: Katie Touart Projections Designer: Dylan Uremovich Sound Designer: Nick Hernandez Properties Designer: Willow Watson Movement Specialist: Tony Thomas* Production Stage Manager: Simone Baskerville* Dramaturg: Isaiah M. Wooden & Khalid Yaya Long Table of Contents Curriculum Connections: DC Public -

Native Sons Or Invisible Men?

NATIVE SONS OR INVISIBLE MEN? The Afro-American Search for Identity in 20th-Century America as portrayed in Richard Wright’s Native Son and Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man and an Adaptation of the Topic for the English Classroom Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Magisters der Philosophie an der Philologisch-Kulturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Leopold-Franzens-Universität Innsbruck Eingereicht bei Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Gudrun M. Grabher Institut für Amerikastudien von Mag. Martin Alexander Delucca, BA Innsbruck, im Februar 2020 Native Sons or Invisible Men? 2 To Be Great Is to Be Misunderstood Ralph Waldo Emerson In lieber Errinnerung an meine außergewöhnliche Mami Danke, Sonja, Marco und Nadia. Und Dir, Fabian. Native Sons or Invisible Men? 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface……………………………………………… 5 Introduction……………………………….............. 5 1. The White World Is the Right World…………. 11 1.1.White Supremacy………………………………. 16 1.1.1. Institutions and Their Whitewashing 19 1.1.2. White Status Symbols ………………. 26 1.1.3. Meeting the Daltons…………………….. 31 1.2. Black Microcosms: “A Nation Within the Nation” 39 1.2.1. The Southern World in Invisible Man 40 1.2.2. Black Metropolis…………………….. 44 1.2.3. Meeting the Thomases………………….. 50 2. “Running Nigger Boys”………………………. 53 2.1 Motion in a Static World………………………. 55 2.1.1. Conformity: “I’m Nowhere” ………. 58 2.1.2. Escapism: “Going Nowhere” ………. 63 2.1.3. Supremacist Tendencies: “You Are Nowhere”……………….. 69 2.2. “Machines Inside the Machine”……………… 74 2.3. Communism: Black and Red Brothers?……… 79 Native Sons or Invisible Men? 4 3. Acts of Emancipation and Reconstruction……… 88 3.1. -

Native Son Thesis

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO “Vocal and Physical Endurance that Lasts till the End.” Engaging Your Training in Native Son A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Fine Arts in Theatre and Dance (Acting) by Terrance White Committee in charge: Marc Barricelli, Chair Eva Barnes Charles Oates Manuel Rotenberg 2017 © Terrance White, 2017 All rights reserved. The Thesis of Terrance White is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2017 iii DEDICATION Dedicated to Zara Laniece Mitchell my beautiful niece. Any dreams you have in this world you chase them and uncle will be right there with you to support your entire journey. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page................................................................................................................ iii Dedication....................................................................................................................... iv Table of Contents............................................................................................................ v List of Supplemental Files.............................................................................................. vi Acknowledgements........................................................................................................ vii Abstract of the Thesis.................................................................................................... -

TEMPERATURE RANGE Highs: Mid 70'S Lows

Please note that all of the itineraries listed in our web site are actual private tour itineraries we have prepared for clients over the past 12-18 months. By the very nature of what we do, each private tour itinerary is custom, exclusive and unique unto itself. Our over-riding goal is to create lifelong memories that you and your family will forever carry deep within your hearts. Overview Similar to the Spanish-speaking countries of South America, Spain epitomizes a love-of-life culture with unlimited culinary, historical, and visually striking landscapes. Spain’s three official languages illustrate strong regional distinctions and clue into the cultural mosaic that Spain is. Watch a clip of Spanish national soccer team during the national anthem and you will notice there are no official words due to its highly contrasting languages and regional cultures! One moment you are strolling through the Gaudi-dominated streets of Barcelona and the next, you find yourself immersed in the compelling Moorish history and architecture of the breathtaking Andalucia. You will find that Spain’s history is more rich and profound than ever imagined by taking a private tour with us. TEMPERATURE RANGE Day 1 Highs: Mid 70’s Fly to Barcelona Lows: High 40’s Through our sister company, premium air provider TRAVNET, we may AREA assisted with your international airfare, as well as with mileage points 505,990 SQ KM conversion. 195,364 SQ MILES POPULATION Day 2 46.4 Million Upon Arrival in Barcelona, you will be privately transferred to the LANGUAGE Mandarin Oriental Barcelona. -

Spain + Portugal Private Tour

Spain + Portugal Private Tour Please note that all of the itineraries listed in our web site are actual private tour itineraries we have prepared for clients over the past 12-18 months. By the very nature of what we do, each private tour itinerary is custom, exclusive and unique unto itself. Our over-riding goal is to create lifelong memories that you and your family will forever carry deep within your hearts. Overview Similar to the Spanish-speaking countries of South America, Spain epitomizes a love-of-life culture with unlimited culinary, historical, and visually striking landscapes. Spain’s three official languages illustrate strong regional distinctions and the cultural mosaic that make up this country. Watch a clip of the Spanish national soccer team during the national anthem and you will notice there are no official words due to its highly contrasting languages and regional cultures! One moment you are strolling through the Gaudi-dominated streets of Barcelona and the next, you find yourself immersed in the compelling Moorish history and architecture of the breathtaking Andalucía. In tandem with Spain, the small but impressive country of Portugal awaits to amaze you! Due to its long and slim geography, there are 600 miles of beautiful coastline along the Atlantic Ocean, offering stunning views from almost anywhere you visit. Although tourism has been on the rise, it is one of the few places in Europe that does not have an overpopulation of visitors. With such a tie to the ocean, the seafood in Portugal is an important part of the cuisine and culture and is always fresh and delicious! If you are a wine lover, you will be pleasantly surprised by the selection and harvest that takes place throughout the country including the Port and Madeiran wines. -

A Bogus Hero: Welles's Othello and the Construction of Race

A Bogus Hero: Welles’s Othello and the Construction of Race Nicholas Jones Oberlin College “. his Lears and Othellos all seemed a little bogus . .” (Thomson 355) Welles’s 1952 film of Othello is as much Welles as it is Othello.1 It is stamped with the persona of its prime mover, who raised the money, wrote the script, directed the film, and acted the lead role. As director, Welles dominates the film with his personality and his style. As principal actor, Welles is by far the strongest presence in the film: his prominent body dominates the screen, his voice is the most memorable and often the only understandable part of the flawed soundtrack, and he far out-acts the doll-like Suzanne Cloutier (Desdemona) and the wasted Micheál MacLiammóir (Iago). The persona of Orson Welles has predictably determined much of the history of interpretation of the film. Now seen largely as a part of the Welles oeuvre, it is seen to participate in, variously, the mystery–biography genre (Citizen Kane); the interrogation of modernist progress (The Magnificent Ambersons); or the introduction of Shakespearean culture into modern popular genres (Everybody’s Shakespeare and the “voodoo” Macbeth).2 Welles has so clearly stamped his personality on this film that the filmmaker and his main character seem intertwined. Jones 2 Welles not only played Othello with enormous relish in this film (about which he cared deeply) but seemed to bring Shakespeare’s hero into his own very public life, which sometimes reads like Othello’s "traveler’s history"–a restless wandering among grand projects, illuminated by flashes of genius, and destined for self-destruction and exile.3 Like the Ronald Colman character in George Cukor’s A Double Life, Welles might seem to have identified with Shakespeare’s tragic hero.