Cultural Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download to View

The Mao Era in Objects Money (钱) Helen Wang, The British Museum & Felix Boecking, University of Edinburgh Summary In the early twentieth century, when the Communists gained territory, they set up revolutionary base areas (also known as soviets), and issued new coins and notes, using whatever expertise, supplies and technology were available. Like coins and banknotes all over the world, these played an important role in economic and financial life, and were also instrumental in conveying images of the new political authority. Since 1949, all regular banknotes in the People’s Republic of China have been issued by the People’s Bank of China, and the designs of the notes reflect the concerns of the Communist Party of China. Renminbi – the People’s Money The money of the Mao era was the renminbi. This is still the name of the PRC's currency today - the ‘people’s money’, issued by the People’s Bank of China (renmin yinhang 人民银 行). The ‘people’ (renmin 人民) refers to all the people of China. There are 55 different ethnic groups: the Han (Hanzu 汉族) being the majority, and the 54 others known as ethnic minorities (shaoshu minzu 少数民族). While the term renminbi (人民币) deliberately establishes a contrast with the currency of the preceding Nationalist regime of Chiang Kai-shek, the term yuan (元) for the largest unit of the renminbi (which is divided into yuan, jiao 角, and fen 分) was retained from earlier currencies. Colloquially, the yuan is also known as kuai (块), literally ‘lump’ (of silver), which establishes a continuity with the silver-based currencies which China used formally until 1935 and informally until 1949. -

CHINA TODAY China’S Importance on the Global Landscape in Indisputable

02.2016 Certified International Property Specialist TO LOCAL, INTERNATIONAL & LIFESTYLE REAL ESTATE > UPDATE ON CHINA What Global Agents Need to Know About CHINA TODAY China’s importance on the global landscape in indisputable. Its purchasing power, amplifi ed by several years of strong economic growth and the sheer size of its population is felt across the globe. Chinese investors—including individuals, corporations, and institutions—have all displayed a strong appetite for real property beyond their borders. Will the trend continue in 2016? Probably, yes. Even though the country’s roaring economic engine has cooled, there are many reasons to expect overseas property purchases to remain strong. In fact, some segments of the market and destinations may witness even more robust interest. That’s because, as a rule, Chinese buyers do their homework. If the numbers don’t add up because prices are too high, they’ll explore other locations. At the same time, Chinese buyers are also well represented in the global luxury market, where sky-high prices are seldom deal-breakers. As a nation, China has been taking signifi cant steps aimed at more fully joining the world’s economic leaders. Even if you aren’t directly aff ected by these developments, it’s important to be informed about them, especially if you’re working with Chinese clients. This issue will get you up to speed. Inside, you’ll also fi nd an update on the latest overseas buying trends among Chinese investors—tips that can be extremely benefi cial in marketing to and working with clients. PROPERTYUPDATE ON PORTALSPO CHINATA KEY ECONOMIC & FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS IN CHINA Just over a year ago, China overtook the U.S. -

Arresting Flows, Minting Coins, and Exerting Authority in Early Twentieth-Century Kham

Victorianizing Guangxu: Arresting Flows, Minting Coins, and Exerting Authority in Early Twentieth-Century Kham Scott Relyea, Appalachian State University Abstract In the late Qing and early Republican eras, eastern Tibet (Kham) was a borderland on the cusp of political and economic change. Straddling Sichuan Province and central Tibet, it was coveted by both Chengdu and Lhasa. Informed by an absolutist conception of territorial sovereignty, Sichuan officials sought to exert exclusive authority in Kham by severing its inhabitants from regional and local influence. The resulting efforts to arrest the flow of rupees from British India and the flow of cultural identity entwined with Buddhism from Lhasa were grounded in two misperceptions: that Khampa opposition to Chinese rule was external, fostered solely by local monasteries as conduits of Lhasa’s spiritual authority, and that Sichuan could arrest such influence, the absence of which would legitimize both exclusive authority in Kham and regional assertions of sovereignty. The intersection of these misperceptions with the significance of Buddhism in Khampa identity determined the success of Sichuan’s policies and the focus of this article, the minting and circulation of the first and only Qing coin emblazoned with an image of the emperor. It was a flawed axiom of state and nation builders throughout the world that severing local cultural or spiritual influence was possible—or even necessary—to effect a borderland’s incorporation. Keywords: Sichuan, southwest China, Tibet, currency, Indian rupee, territorial sovereignty, Qing borderlands On December 24, 1904, after an arduous fourteen-week journey along the southern road linking Chengdu with Lhasa, recently appointed assistant amban (Imperial Resident) to Tibet Fengquan reached Batang, a lush green valley at the western edge of Sichuan on the province’s border with central Tibet. -

Chinese Zheng and Identity Politics in Taiwan A

CHINESE ZHENG AND IDENTITY POLITICS IN TAIWAN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN MUSIC DECEMBER 2018 By Yi-Chieh Lai Dissertation Committee: Frederick Lau, Chairperson Byong Won Lee R. Anderson Sutton Chet-Yeng Loong Cathryn H. Clayton Acknowledgement The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the support of many individuals. First of all, I would like to express my deep gratitude to my advisor, Dr. Frederick Lau, for his professional guidelines and mentoring that helped build up my academic skills. I am also indebted to my committee, Dr. Byong Won Lee, Dr. Anderson Sutton, Dr. Chet- Yeng Loong, and Dr. Cathryn Clayton. Thank you for your patience and providing valuable advice. I am also grateful to Emeritus Professor Barbara Smith and Dr. Fred Blake for their intellectual comments and support of my doctoral studies. I would like to thank all of my interviewees from my fieldwork, in particular my zheng teachers—Prof. Wang Ruei-yu, Prof. Chang Li-chiung, Prof. Chen I-yu, Prof. Rao Ningxin, and Prof. Zhou Wang—and Prof. Sun Wenyan, Prof. Fan Wei-tsu, Prof. Li Meng, and Prof. Rao Shuhang. Thank you for your trust and sharing your insights with me. My doctoral study and fieldwork could not have been completed without financial support from several institutions. I would like to first thank the Studying Abroad Scholarship of the Ministry of Education, Taiwan and the East-West Center Graduate Degree Fellowship funded by Gary Lin. -

About Beijing

BEIJING Beijing, the capital of China, lies just south of the rim of the Central Asian Steppes and is separated from the Gobi Desert by a green chain of mountains, over which The Great Wall runs. Modern Beijing lies on the site of countless human settlements that date back half a million years. Homo erectus Pekinensis, better known as Peking man was discovered just outside the city in 1929. It is China's second largest city in terms of population and the largest in administrative territory. The name Beijing - or Northern Capital - is a modern term by Chinese standards. It first became a capital in the Jin Dynasty (1115-1234), but it experienced its first phase of grandiose city planning in the Yuan Dynasty under the rule of the Mongol emperor, Kublai Khan, who made the city his winter capital in the late 13th century. Little of it remains in today's Beijing. Most of what the visitor sees today dates from either the Ming or later Qing dynasties. Huge concrete tower blocks have mushroomed and construction sites are everywhere. Bicycles are still the main mode of transportation but taxis, cars, and buses jam the city streets. PASSPORT/VISA CONDITIONS All visitors to Beijing and the People's Republic of China are required to have a valid passport (one that does not expire for at least 6 months after your arrival date in China). A special tourist or business visa is also required. CUSTOMS Travelers are allowed to bring into China one bottle of alcoholic beverages and two cartons of cigarettes. -

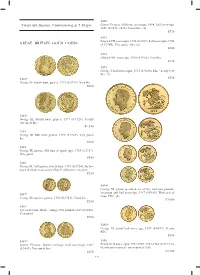

Twentieth Session, Commencing at 7.30 Pm GREAT BRITAIN GOLD

5490 Twentieth Session, Commencing at 7.30 pm Queen Victoria, old head, sovereign, 1898; half sovereign, 1896 (S.3874, 3878). Good fi ne. (2) $570 5491 Edward VII, sovereigns, 1905 (S.3969); half sovereigns, 1908 GREAT BRITAIN GOLD COINS (S.3974B). Very good - fi ne. (2) $500 5492 Edward VII, sovereign, 1910 (S.3969). Very fi ne. $370 5493 George V, half sovereigns, 1912 (S.4006). Fine - nearly very fi ne. (2) $350 5482* George III, fourth bust, guinea, 1774 (S.3728). Very fi ne. $600 5483* George III, fourth bust, guinea, 1777 (S.3728). Nearly extremely fi ne. $1,350 5484 George III, fi fth bust, guinea, 1787 (S.3729). Very good/ fi ne. $500 5485 George III, guinea, fi fth bust of spade type, 1788 (S.3729). Very good. $450 5486 George III, half guinea, fourth bust, 1781 (S.3734). Surface marked (from wear as jewellery?), otherwise very fi ne. $250 5494* George VI, proof specimen set of fi ve and two pounds, sovereign and half sovereign, 1937 (S.PS15). With case of 5487* issue, FDC. (4) George III, quarter guinea, 1762 (S.3741). Good fi ne. $7,000 $250 5488 Queen Victoria, Jubilee coinage, two pounds, 1887 (S.3865). Very good. $700 5495* George VI, proof half sovereign, 1937 (S.4077). Nearly FDC. $850 5489* 5496 Queen Victoria, Jubilee coinage, half sovereign, 1887 Elizabeth II, sovereigns, 1957-1959, 1962-1968 (S.4124, 5). (S.3869). Extremely fi ne. Nearly uncirculated - uncirculated. (10) $250 $3,700 532 5497 Elizabeth II, proof sovereigns, 1979 (S.4204) (2); proof half sovereigns, 1980 (S.4205) (2). -

English Program

B. English Scholarly Program Papers marked with ** are best paper award winners. Day 1, June 14, 2018, Thursday CEO International Work Experience and Firms’ Temporal Orientation: From A Lens of Executive Session 02 Keynote Panel - Meeting Job Demands Challenges of Continuous Transformation Cuili Qian, The University of Texas at Dallas Sponsored by Wuhan University, Economics and Gary Lipeng Ge, University of Groningen Management School Tianyu Gong, The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology 武汉大学经济与管理学院冠名赞助 Giving Green an Office: The Effectiveness of Time: 08:30-10:30 Chief Sustainability Officer Presence Room: Jingchu Hall Yi Tang, Hong Kong Baptist University Chair/Discussant: Ruchunyi Fu, City University of Hong Kong Zhi-Xue Zhang, Peking University Guoli Chen, European Institute of Business Administration Network Advantage in China versus the West Do Military CEOs Foster Corporate Innovation? Evidence from China Ronald Burt, University of Chicago Dayuan Li, Central South University Entrepreneurship Environments: Community Yini Zhao, Central South University Effects on Organizations TMT Dispositional Optimism Composition Daily Sessions in Detail Program Henrich Greve, INSEAD and Firm Performance: The Mediating Role of Micro Foundations for Meeting New Challenges Competitive Actions English Scholarly Program B. in a New Era of Transformation: Insights from Jianhong Chen, University of New Hampshire Creativity and Innovation Research Tianxu Chen, Portland State University Jing Zhou, Rice University Ho Kwong Kwan, Tongji University Sucheta Nadkarni, University of Cambridge Session 3A (Paper) - Inside the Executive Suite Sponsored by Central China Normal Session 3B (Paper) - Creativity University, School of Economics and Business Administration Time: June 14, 2018, 10:45 - 12:15 华中师范大学经济与工商管理学院冠名赞助 Room: Xiangyang Chair/ Discussant: Yaping Gong, The Hong Kong Time: June 14, 2018, 10:45 - 12:15 University of Science and Technology Room: Wuhan Chair/ Discussant: Carl F. -

CAST COINAGE of the MING REBELS John E. Sandrock

CAST COINAGE OF THE MING REBELS John E. Sandrock Collecting China's ancient coins can be a very worthwhile and rewarding experience. While at first glance this endeavor may appear overwhelming to the average Westerner, it is in reality not difficult once you master a few guidelines and get the hang of it. Essential to a good foundation of knowledge is a clear understanding of the chronology of dynasties, the evolution of the cash coin from ancient to modern times, the Chinese system of dating, the Nien Hao which identifies the coin to emperor and thus to dynasty, and the various forms of writing (calligraphy) used to form the standard characters. Once this basic framework is mastered, almost all Chinese coins fall into one dynastic category or another, facilitating identification and collection. Some do not, however, which brings us to the subject at hand. The coins of the Ming Rebels defy this pattern, as they fall between two dynasties, overlapping both. Thus they do not fit nicely into one category or another and consequently must be treated separately. To put this into historical perspective it is necessary to know that the Ming dynasty lasted from 1368 to the year 1644 and that its successor, the Ch'ing dynasty, existed from 1644 to its overthrow in 1911. Therefore our focus is on the final days of the Ming and beginning of the Ch'ing dynasties. The Ming era was a period of remarkable accomplishment. This was a period when the arts and craftsmanship flourished. Administration and learning soared to new heights. -

From Chinese Silver Ingots to the Yuan

From Chinese Silver Ingots to the Yuan With the ascent of the Qing Dynasty in 1644, China's modern age began. This epoch brought foreign hegemony in a double sense: On the one hand the Qing emperors were not Chinese, but belonged to the Manchu people. On the other hand western colonial powers began to influence politics and trade in the Chinese Empire more and more. The colonial era brought a disruption of the Chinese currency history that had hitherto shown a remarkable continuity. Soon, the Chinese money supply was dominated by foreign coins. This was a big change in a country that had used simple copper coins only for more than two thousand years. 1 von 11 www.sunflower.ch Chinese Empire, Qing Dynasty, Sycee Zhong-ding (Boat Shape), Value 10 Tael, 19th Century Denomination: Sycee 10 Tael Mint Authority: Qing Dynasty Mint: Undefined Year of Issue: 1800 Weight (g): 374 Diameter (mm): 68.0 Material: Silver Owner: Sunflower Foundation A major characteristic of Chinese currency history is the almost complete absence of precious metals. Copper coins dominated monetary circulation for more than 2000 years. Paper money was invented at an early stage - primarily because the coppers were too unpractical for large transactions. The people's confidence in paper money was limited, however. Hence silver became a common standard of value, primarily in the form of ingots. The use of ingots as means of payment dates back 2000 years. However, because silver ingots were smelted now and again, old specimens are very rare. This silver ingot in the shape of a boat – Yuan Bao in Chinese – dates from the Qing dynasty (1644-1911). -

The Circulation of Foreign Silver Coins in Southern Coastal Provinces of China 1790-1890

The Circulation of Foreign Silver Coins in Southern Coastal Provinces of China 1790-1890 GONG Yibing A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in History •The Chinese University of Hong Kong August 2006 The Chinese University of Hong Kong holds the copyright of this thesis. Any person(s) intending to use a part or whole of the materials in the thesis in a proposed publication must seek copyright release from the Dean of the Graduate School. /y統系位書口 N^� pN 0 fs ?jlj ^^university/M \3V\ubrary SYSTEM^^ Thesis/Assessment Committee Professor David Faure (Chair) Professor So Kee Long (Thesis Supervisor) Professor Cheung Sui Wai (Committee Member) 論文評審委員會 科大衛教授(主席) 蘇基朗教授(論文導師) 張瑞威教授(委員) ABSTRACT This is a study of the monetary history of the Qing dynasty, with its particular attentions on the history of foreign silver coins in the southern coastal provinces, or, Fujian, Guangdong, Jiangsu and Zhejiang, from 1790 to 1890. This study is concerned with the influx of foreign silver coins, the spread of their circulation in the Chinese territory, their fulfillment of the monetary functions, and the circulation patterns of the currency in different provinces. China, as a nation, had neither an integrated economy nor a uniform monetary system. When dealing with the Chinese monetary system in whatever temporal or spatial contexts, the regional variations should always be kept in mind. The structure of individual regional monetary market is closely related to the distinct regional demand for metallic currencies, the features of regional economies, the attitudes of local governments toward certain kinds of currencies, the proclivities of local people to metallic money of certain conditions, etc. -

Oxford University Press. No Part of This Book May Be Distributed, Posted, Or

xix Gaining Currency xx 1 CHAPTER 1 A Historical Prologue At the end of the day’s journey, you reach a considerable town named Pau- ghin. The inhabitants worship idols, burn their dead, use paper money, and are the subjects of the grand khan. The Travels of Marco Polo the Venetian, Marco Polo uch was the strange behavior of the denizens of China in the Sthirteenth century, as narrated by Marco Polo. Clearly, using paper money was a distinguishing characteristic of the peoples the famed itinerant encountered during his extensive travels in China, one the explorer equated with what Europeans would have regarded as pagan rituals. Indeed, the notion of using paper money was cause for wonderment among Europeans at the time and for centuries thereafter; paper money came into use in Europe only during the seventeenth century, long after its advent in China. That China pioneered the use of paper money is only logical since paper itself was invented there during the Han dynasty (206 BC– 220 AD). Cai Lun, a eunuch who entered the service of the imperial palace and eventually rose to the rank of chief eunuch, is credited with the invention around the year 105 AD. Some sources indicate that paper had been invented earlier in the Han dynasty, but Cai Lun’s achievement was the development of a technique that made the mass production of paper possible. This discovery was not the only paper- making accomplishment to come out of China; woodblock printing and, subsequently, 2 movable type that facilitated typography and predated the Gutenberg printing press by about four centuries can also be traced back there. -

Proquest Dissertations

TO ENTERTAIN AND RENEW: OPERAS, PUPPET PLAYS AND RITUAL IN SOUTH CHINA by Tuen Wai Mary Yeung Hons Dip, Lingnan University, H.K., 1990 M.A., The University of Lancaster, U.K.,1993 M.A., The University of British Columbia, Canada, 1999 A THESIS SUBIMTTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September 2007 @ Tuen Wai Mary Yeung, 2007 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-31964-2 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-31964-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these.