Institutionalised Protest and the Policing of Public Order

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joint Committee on Human Rights

House of Lords House of Commons Joint Committee on Human Rights Demonstrating Respect for Rights? Follow–up Twenty-second Report of Session 2008–09 Report, together with formal minutes and oral and written evidence Ordered by the House of Lords to be printed 14 July 2009 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 14 July 2009 HL Paper 141 HC 522 Published on 28 July 2009 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 Joint Committee on Human Rights The Joint Committee on Human Rights is appointed by the House of Lords and the House of Commons to consider matters relating to human rights in the United Kingdom (but excluding consideration of individual cases); proposals for remedial orders, draft remedial orders and remedial orders. The Joint Committee has a maximum of six Members appointed by each House, of whom the quorum for any formal proceedings is two from each House. Current membership HOUSE OF LORDS HOUSE OF COMMONS Lord Bowness John Austin MP (Labour, Erith & Thamesmead) Lord Dubs Mr Andrew Dismore MP (Labour, Hendon) (Chairman) Lord Lester of Herne Hill Dr Evan Harris MP (Liberal Democrat, Oxford West & Lord Morris of Handsworth OJ Abingdon) The Earl of Onslow Mr Virendra Sharma MP (Labour, Ealing, Southall) Baroness Prashar Mr Richard Shepherd MP (Conservative, Aldridge-Brownhills) Mr Edward Timpson MP (Conservative, Crewe & Nantwich) Powers The Committee has the power to require the submission of written evidence and documents, to examine witnesses, to meet at any time (except when Parliament is prorogued or dissolved), to adjourn from place to place, to appoint specialist advisers, and to make Reports to both Houses. -

Matchgirls’ Strike - Labour History Museum Pictures from Windscale Postcards Photography and the Law

m f. Mm Postcard of YVindscale 1979 Mike Abrahams The Fashion Spread Blair Peach - No Cover Up Matchgirls’ Strike - Labour History Museum Pictures from Windscale Postcards Photography and the Law No 17 Half Moon Photography Workshop 60p/$1.75 CAMERAWORK 1 Lcs nouveau \ T-shirlvdcbjrdcurx rcsscmblcnt .i lout saufa la chcrrmc dev dockets: ils sapparenteni plutot aux maillots dc danseuses modcrncs uvee leurs munches longues, leurs prolonds decolleics.ou uus hauls dc tutus avee leurs brcielles ct leurcorsuttebusiier A gauche. T-shirt a munches longues en jersey de colon dc Jjck>tcx. ci sa jupc portclcuillc cn jersey dc colon rouge reversible rosede Jack vies, Gianni Versace pour Callaghan SanJ.ilcs Charles Jourdan A df.. T-shirt bustier cn jersey de coion ct sa jupc fronccc cn mcme jersey. Dominique Peelers pourGuilare Sandalcs Charles Jourdan Au centre, bustier a brcielles cn jersey de coion cl short assorti. (juitarc. Coiffures Valentin pour Jcan-l OW9 DlV <1 Maquillagcs Lancaster: tcints hales ct unil'ics avee Visage Bmn/c. Photo prise a I'I Intel I oniainebleau a Miami Bench. Tics gai. pour lous les instants dc voire v ie: “CabriolcT le nouveau parluni dbli/ubctli Arden. Guy Bourdin, French Vogue May 1978: To turn the page is not only to open and close the spectacle of the fashion spread but to cut up the figure with which we are spatially identified - to open and close her legs. Fashion photography as anonymous history graphers are inclined to regard the economic and techno familiar. Perhaps what is needed is what Siegfried Gideon Fashion photography is traditionally regarded as the light logical processes as a ‘threat’ to their domain - the taking of calls ‘anonymous history’: an account of the effects of tech weight end of photographic practice. -

References Ready for Transfer to WORD

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: McIntosh, S. (2016). Open justice and investigations into deaths at the hands of the police, or in police or prison custody. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City, University of London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/15340/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Open Justice and Investigations into Deaths at the Hands of the Police, or in Police or Prison Custody By Sam McIntosh PhD Candidate CITY UNIVERSITY, LONDON LAW SCHOOL FEBRUARY 2016 i CONTENTS Table of Contents ii Table of Cases (England and Wales) x Table of Cases (ECtHR and ECmHR) xii Table of Cases (other Jurisdictions) xiv Table of Statutes and Bills xvi Table of Statutory Instruments -

Policing Large Scale Disorder: Lessons from the Disturbances of August 2011

House of Commons Home Affairs Committee Policing Large Scale Disorder: Lessons from the disturbances of August 2011 Sixteenth Report of Session 2010–12 Additional written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be published 22 December 2011 Published on 22 December 2011 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited The Home Affairs Committee The Home Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Home Office and its associated public bodies. Current membership Rt Hon Keith Vaz MP (Labour, Leicester East) (Chair) Nicola Blackwood MP (Conservative, Oxford West and Abingdon) James Clappison MP (Conservative, Hertsmere) Michael Ellis MP (Conservative, Northampton North) Lorraine Fullbrook MP (Conservative, South Ribble) Dr Julian Huppert MP (Liberal Democrat, Cambridge) Steve McCabe MP (Labour, Birmingham Selly Oak) Rt Hon Alun Michael MP (Labour & Co-operative, Cardiff South and Penarth) Bridget Phillipson MP (Labour, Houghton and Sunderland South) Mark Reckless MP (Conservative, Rochester and Strood) Mr David Winnick MP (Labour, Walsall North) The following members were also members of the committee during the parliament. Mr Aidan Burley MP (Conservative, Cannock Chase) Mary Macleod MP (Conservative, Brentford and Isleworth) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at www.parliament.uk/homeaffairscom. -

Pdf, 511.2 Kb

IN THE UNDERCOVER POLICING INQUIRY OPENING SUBMISSIONS ON BEHALF OF CORE PARTICIPANTS SET OUT IN AN ANNEX REPRESENTED BY HODGE JONES & ALLEN, BHATT MURPHY AND BINDMANS SOLICITORS INTRODUCTION 1. This opening statement is made on behalf of over 100 individuals and groups, all of whom are Core Participants in this Inquiry. 2. All of them were subjected to undercover police surveillance that was inappropriate, improperly regulated, and abused their rights. They want answers from this Inquiry and ask that this Inquiry makes recommendations that prevent this experience happening to others. 3. These Core Participants come from a wide variety of backgrounds, ages, ethnicities and political views. But they all share an outrage at the experience each of them suffered. They deserve answers for the experiences they suffered through undercover policing to which none of them should have been subjected. Those officers and their supervisors, who committed that wrongdoing must be called to account, as must be the system that permitted it. 4. The experiences of these Core Participants spans more than a 40 year period from 1968 to the present date. They are people who campaigned – and still campaign – on a variety of different issues. Some have remained community activists, others have continued to seek justice for family members who were killed. Others have become senior political figures – including Members of Parliament, and a member of the House of Lords who is also a former Secretary of State. 5. A common feature that unites their experience is that the police surveillance to which they were subjected was not merely out of control, but was politicised. -

Pdf, 168.42 Kb

1 1 Thursday, 6 May 2021 2 (10.00 am) 3 MR FERNANDES: Good morning, everyone, and welcome to Day 11 4 of hearings in Tranche 1 Phase 2 at 5 the Undercover Policing Inquiry. 6 My name is Neil Fernandes and I am the hearings 7 manager. For those of you in the virtual hearing room, 8 please turn off both your camera and microphone unless 9 you are invited to speak by the Chairman, as Zoom will 10 pick up on all noises and you will be on screen. 11 I will now hand over to the Chairman, 12 Sir John Mitting, to formally start proceedings. 13 Chairman. 14 THE CHAIRMAN: Thank you. 15 Ms Campbell. 16 Summary of evidence of the family of HN300/"Jim Pickford" 17 MS CAMPBELL: Thank you, Sir. 18 I will begin by summarising the statement given to 19 the Inquiry by the family of HN300; cover name 20 "Jim Pickford". 21 The statement was made in December 2017, during 22 the course of the Inquiry's anonymity proceedings, and 23 is a joint statement by HN300's second wife, to whom he 24 was married during his deployment, and his two 25 daughters. HN300 is now deceased. 2 1 Due to the nature of this statement, I'll be 2 summarising certain sections and reading others in full. 3 The full statement will be published on the Inquiry's 4 website today. 5 The statement begins with the family stating their 6 concerns about the real name of HN300 being disclosed 7 through the Inquiry. -

The London School of Economics and Political Science Policing Minority

The London School of Economics and Political Science Policing minority ethnic communities: A case study in London’s ‘Little India’ Sara Trikha A thesis submitted to the Department of Sociology of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, December 2012. Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 94,284 words. The bibliography of my thesis was typed by David Church. Sara Trikha 1 Abstract The Macpherson Inquiry (1999) was instrumental in forcing into the public domain the issue of police racism, which for decades had been an endemic part of police culture. My thesis, undertaken post Macpherson (1999), examined ongoing tensions in the policing of minority ethnic communities through a case study of policing in London’s ‘Little India’. My thesis highlights the continuing influence of racism in policing, describing a world of policing ethnically diverse communities that is far more complex, variable and contradictory than has yet been documented in the empirical policing literature. I describe how policing in Greenfield was a patchwork of continuity and change, illustrating how, despite the advances the police in Greenfield had made in eradicating overt racism from the organisation, passive prejudice remained rife among officers. -

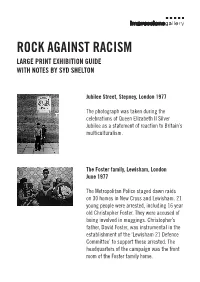

Rock Against Racism Large Print Exhibition Guide with Notes by Syd Shelton

ROCK AGAINST RACISM LARGE PRINT EXHIBITION GUIDE WITH NOTES BY SYD SHELTON Jubilee Street, Stepney, London 1977 The photograph was taken during the celebrations of Queen Elizabeth II Silver Jubilee as a statement of reaction to Britain’s multiculturalism. The Foster family, Lewisham, London June 1977 The Metropolitan Police staged dawn raids on 30 homes in New Cross and Lewisham. 21 young people were arrested, including 16 year old Christopher Foster. They were accused of being involved in muggings. Christopher’s father, David Foster, was instrumental in the establishment of the ‘Lewisham 21 Defence Committee’ to support those arrested. The headquarters of the campaign was the front room of the Foster family home. Jubilee Street, Stepney, London 1977 Lewisham, London, 13 August 1977 Lewisham youth show off the braid ripped from a flag of the National Front ‘Honour Garde’. New Cross Road, Lewisham, London 13 August 1977 National Front marchers. Lewisham, London 13 August 1977 Demonstrators taking part in what has been known as the ‘Anti-Anti Mugging March’ in response to the National Front’s ‘Anti- Mugging March’. Some 5,000 local people and anti-racist activists occupied New Cross Road. A quarter of the Metropolitan police, together with their entire mounted division, were deployed as escort to the National Front demonstration. New Cross, London 13 August 1977 Long after the National Front had been bussed out of the area, riot shields were used against protesters for the first time in mainland Britain. Lewisham, London 13 August 1977 National Front demonstrators. New Cross Road, Lewisham, London 13 August 1977 Police charge anti-racist demonstrators. -

Briefing on the Death of Ian Tomlinson

Briefing on the death of Ian Tomlinson June 2009 INQUEST - Briefing on the death of Ian Tomlinson 1. INQUEST is working with the family and lawyers1 of 47 year old Ian Tomlinson who was caught up in the police response to the G20 protests while he walked home in the City of London on 1 April 2009. Alongside the provision of casework support INQUEST is conducting policy and parliamentary work on the issues arising from the death of Mr Tomlinson and its investigation. The events surrounding this death are profoundly alarming and raise questions about police powers, tactics and accountability. 2. This briefing is informed by our area of expertise – deaths in detention or following contact with state agents. As these deaths represent the most severe end of a continuum of police violence, incompetence, neglect and potential criminality, the lessons that can be learned from bereaved families and their representatives are particularly important. 3. INQUEST is concerned that the disturbing issues surrounding the death of Ian Tomlinson could have been swept under the carpet and the cause of his death dismissed as being from 'natural causes' without the benefit of the video footage and photographs that entered the public domain to challenge directly the police version of events. 4. The controversial circumstances surrounding Mr Tomlinson’s death require robust, independent and transparent investigation. His death also raises wider contextual questions about: a. The police planning, operation, command and control of the G20 protests: b. the lines of accountability and control in relation to joint police operations; c. the role of the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) Territorial Support Group (TSG); d. -

Exhibit to Witness Statement of Celia Stubbs

DOCUMENTS REFERRED TO IN THE FIRST WITNESS STATEMENT OF CELIA STUBBS 1. The Cass Report, 14 September 1979 (front page and conclusions) 2. The Blair Peach Case: Licence to Kill, David Ransom (extracts) UCPI0000034077/1 METRO POLIT AN POLICE Subject Complaints Investigation Bureau (2) Death of Clement New Scotland Yard Blair PEACH at Southall 23.04.79 CONFIDENTIAL 14th day of September 1979 Reference to Papers OG 1/79/2234 SECOND REPORT - DEATH OF BLAIR PEACH Director C.I.B. 237. Further to my first report dated 12th July, 1979, concerning enquiries into the death of Clement Blair PEACH. No additional evidence of great significance has emergedin relation to the death. IDENTIFICATION PARADE 238. A number of identification parades have since been held in connection with the death, but no positive identification of any officer has been made. 239. Identification parades were also held in connection with other incidents that had occurred in the vicinity at about the same time. At identification parades held on the 1st August, 1979, at Wembley Police Station, Officer I ************* and Officer 38 ************* were put up as UCPI0000034077/2 CONCLUSIONS 293. Despite extensive enquiries made into the death of Blair PEACH and the surrounding circumstances, it has not been possible to establish exactly what caused the injury or who struck the fatal blow. 294. It is not possible to state with certainty whether the death resulted from an unlawful act. As pointed out in the FIRST report there are a number of witnesses who say that they saw PEACH struck by a police officer and there is no evidence to show that he received the injury to the side of his head in any other way. -

Adapting to Protest – Nurturing the British Model of Policing Contents �

Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Constabulary – Adapting to Protest – Nurturing the British Model of Policing Protest to – Adapting of Constabulary Chief Inspector Her Majesty’s ADAPTING TO PROTEST– NURTURING THE BRITISH MODEL OF POLICING The report is available in alternative languages and formats on request. Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary Ashley House 2 Monck Street London SW1P 2BQ Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Constabulary This report is also available from the HMIC website http://inspectorates.justice.gov.uk/hmic Published in November 2009. Printed by the Central Office of Information. © Crown copyright 2009 ISBN: 978-1-84987-112-9 Ref: 299011 Merseyside 2008, “Hope Not Hate” – With kind permission of Diverse Magazine CONTENTS � Key Findings and Recommendations 5 Executive Summary 11 � Summary Table of Findings 18 � INTRODUCTION: The Challenges Facing Public Order Policing 26 � CHAPTER 1: International Comparisons of Policing Protest 39 � A. International Review of the Policing of Protest 39 � B. Independent Third Party Arbiters 44 � CHAPTER 2: National Standards for Public Order Policing 51 � A. National Review of Policing Protest 53 � B. Developing Consistency for Public Order Policing 66 � Conclusion 69 � CHAPTER 3: Communication 73 � Case Study A: Dialogue Policing In Sweden 74 � Case Study B: Policing Contentious Parades and Protests in Northern Ireland 77 � Case Study C: Communication Models in Murder Investigation 79 � Conclusion 81 � CHAPTER 4: Crowd Dynamics and Public Order Policing 85 � A. Crowd Psychology and Public Order Policing 85 � B. Experiences of Policing Large Scale Football Events 87 � Conclusion 89 � 2 Adapting to Protest – Nurturing the British Model of Policing Contents � CHAPTER 5: Review of Public Order Units � 93 A. -

METROPOLITAN POLICE Subject Death of Clement Blair

METROPOLITAN POLICE Subject Complaints Investigation Bureau (2) Death of Clement New Scotland Yard Blair PEACH at Southall 23.04.79 CONFIDENTIAL 14th day of September 1979 Reference to Papers OG1/79/2234 SECOND REPORT - DEATH OF BLAIR PEACH Director C.I.B. 237. Further to my first report dated 12th July, 1979, concerning enquiries into the death of Clement Blair PEACH. No additional evidence of great significance has emerged in relation to the death. IDENTIFICATION PARADE 238. A number of identification parades have since been held in connection with the death, but no positive identification of any officer has been made. 239. Identification parades were also held in connection with other incidents that had occurred in the vicinity at about the same time. At identification parades held on the 1st August, 1979, at Wembley Police Station, Officer I ************* and Officer 38 ************* were put up as likely suspects for the alleged assault on Person U in the cul-de-sac in the vicinity of 82 Orchard Avenue. Mistaken identifications were made by Stat. Page No. 2737 witnesses Person U, Person 156 and Person 157. It has Stat. Page No. 2797 been established beyond any doubt that the officers picked Stat. Page No. 2738 out were not on duty at the demonstration Stat. Page No. 2740 on the 23rd April, 1979. Officer 85, Officer 86 and Stat. Page No. 2742 Officer 87, the officers were mistakenly identified, have Stat. Page No. 2743 each made statements which are attached. In view of these identifications further parades in respect of the incident were not held for Officer 41, Officer 36 and Officer 43.