In 2004, the University of Queensalnd Successfully Obtained a Three-Year

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchOnline at James Cook University Final Report Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward? Allan Dale, Melissa George, Rosemary Hill and Duane Fraser Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward? Allan Dale1, Melissa George2, Rosemary Hill3 and Duane Fraser 1The Cairns Institute, James Cook University, Cairns 2NAILSMA, Darwin 3CSIRO, Cairns Supported by the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Programme Project 3.9: Indigenous capacity building and increased participation in management of Queensland sea country © CSIRO, 2016 Creative Commons Attribution Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward? is licensed by CSIRO for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Australia licence. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: 978-1-925088-91-5 This report should be cited as: Dale, A., George, M., Hill, R. and Fraser, D. (2016) Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward?. Report to the National Environmental Science Programme. Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited, Cairns (50pp.). Published by the Reef and Rainforest Research Centre on behalf of the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Programme (NESP) Tropical Water Quality (TWQ) Hub. The Tropical Water Quality Hub is part of the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Programme and is administered by the Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited (RRRC). -

Towards Indigenous Co-Management and Biodiversity in the Wet Tropics

Technical Report TROPICAL ECOSYSTEMS hub Framework and Institutional Analysis: Indigenous co-management and biodiversity protection in the Wet Tropics Kirsten Maclean, Rosemary Hill, Petina L. Pert, Ellie Bock, Paul Barrett, Robyn Bellafquih, Michael Friday, Vince Mundraby, Lisa Sarago, Joann Schmider, Leah Talbot Framework analysis: Towards indigenous co-management and biodiversity in the Wet Tropics Kirsten Maclean, Rosemary Hill, Petina L. Pert, Ellie Bock, Paul Barrett, Robyn Bellafquih, Michael Friday, Vince Mundraby, Lisa Sarago, Joann Schmider and Leah Talbot Supported by the Australian Government’s National Environmental Research Program © CSIRO National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: 978-1-921359-74-3 This report should be cited as: Maclean, K., Hill, R., Pert, P.L., Bock, E., Barrett, P., Bellafquih, R., Friday, M., Mundraby, V., Sarago, L., Schmider, S., and L. Talbot (2012), Framework analysis: towards Indigenous co-management and biodiversity in the Wet Tropics. Report to the National Environmental Research Program. Published online by the Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited, Cairns (124pp.). Published by the Reef and Rainforest Research Centre on behalf of the Australian Government’s National Environmental Research Program (NERP) Tropical Ecosystems (TE) Hub. The Tropical Ecosystems Hub is part of the Australian Government’s Commonwealth National Environmental Research Program. The NERP TE Hub is administered in North Queensland by the Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited (RRRC). The NERP Tropical Ecosystem Hub addresses issues of concern for the management, conservation and sustainable use of the World Heritage listed Great Barrier Reef (GBR) and its catchments, tropical rainforests including the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area (WTWHA), and the terrestrial and marine assets underpinning resilient communities in the Torres Strait, through the generation and transfer of world-class research and shared knowledge. -

Pdf, 92.84 KB

A I A T S I S AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF ABORIGINAL AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER STUDIES Native Title Research Unit NATIVE TITLE NEWSLETTER May and June 2001 No. 3/2001 The Native Title Newsletter is published on a bi-monthly basis. The newsletter includes a summary of native title as reported in the press. Although the summary canvasses papers from around Australia, it is not intended to be an exhaustive review of developments. The Native Title Newsletter also includes contributions from people involved in native title research and processes. Views expressed in the contributions are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Contents List of abbreviations........................................................................2 News from the Native Title Research Unit...............................2 Native title in the news..................................................................3 Applications......................................................................................14 Notifications....................................................................................15 Recent publications........................................................................16 Native Title Research Unit publications...................................17 Upcoming conferences NTRBs Legal Conference................................................................2 If you would like to subscribe to the Newsletter electronically, send us an e-mail on -

Tropical Water Quality Hub Indigenous Engagement and Participation Strategy Version 1 – FINAL

Tropical Water Quality Hub Indigenous Engagement and Participation Strategy Version 1 – FINAL NESP Tropical Water Quality Hub CONTENTS ACRONYMS ......................................................................................................................... II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................... II INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 3 OBJECTIVES ........................................................................................................................ 4 IMPLEMENTATION OF THE OBJECTIVES .......................................................................... 5 PERFORMANCE INDICATORS ............................................................................................ 9 IDENTIFIED COMMUNICATION CHANNELS .....................................................................10 FURTHER INFORMATION ..................................................................................................10 APPENDIX A: INDIGENOUS ORGANISATIONS .................................................................11 APPENDIX B: GUIDELINES FOR RESEARCH IN THE TORRES STRAIT ..........................14 VERSION CONTROL REVISION HISTORY Comment (review/amendment Version Date Reviewed by (Name, Position) type) Julie Carmody, Senior Research Complete draft document 0.1 23/04/15 Manager, RRRC 0.2 28/04/15 Melissa George, CEO, NAILSMA Review – no changes 0.3 30/04/15 -

Lessons from Chile for Allocating Indigenous Water Rights in Australia

1130 UNSW Law Journal Volume 40(3) 9 BEYOND RECOGNITION: LESSONS FROM CHILE FOR ALLOCATING INDIGENOUS WATER RIGHTS IN AUSTRALIA ELIZABETH MACPHERSON I INTRODUCTION Australian water law frameworks, which authorise water use, have historically excluded indigenous people. Indigenous land now exceeds 30 per cent of the total land in Australia.1 Yet indigenous water use rights are estimated at less than 0.01 per cent of total Australian water allocations.2 In the limited situations where water law frameworks have engaged with indigenous interests, they typically conceive of such interests as falling outside of the consumptive pool’3 of water applicable to commercial uses associated with activities on land such as irrigation, agriculture, industry or tourism.4 The idea that states must recognise’ indigenous groups, and their ongoing rights to land and resources, has become the central claim of the international indigenous rights movement. 5 Claims for recognition of indigenous land and resource rights are the logical outcome of demands for indigenous rights based on ideas of reparative’ justice.6 The colonisers failed to recognise indigenous rights to land and resources at the acquisition of sovereignty, the argument goes, and the remedy is to recognise those rights now. The dominant legal mechanism BCA, LLB (Hons) (VUW), PhD (Melbourne), Lecturer, School of Law, University of Canterbury. This research was carried out while the author was undertaking a PhD at the University of Melbourne. All translations have been made by the author, with italics used for Spanish language terms. 1 Jon Altman and Francis Markham, Values Mapping Indigenous Lands: An Exploration of Development Possibilities’ (Paper presented at Shaping the Future: National Native Title Conference, Alice Springs Convention Centre, 35 June 2013) 6. -

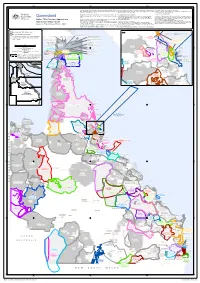

Northern Queensland Region Topographic Vector Data Is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience the Register of Native Title Claims (RNTC), If a Registered Application

142°0'E 144°0'E 146°0'E 148°0'E 150°0'E Hopevale Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from external boundaries with areas excluded or discrete boundaries of Currency is based on the information as held by the NNTT and may not NNTT based on data sourced from Department of Resources (Qld) © areas being claimed) as they have been recognised by the Federal reflect all decisions of the Federal Court. The State of Queensland for that portion where their data has been Court process. To determine whether any areas fall within the external boundary of an used. Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal application or determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and Court, the map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per databases is required. Further information is available from the QUD673/2014 Northern Queensland Region Topographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience the Register of Native Title Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. Tribunals website at www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 Cape York United Number 1 Claim Australia) 2006. The applications shown on the map include: © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 (QC2014/008) Non freehold land tenure sourced from Department of Resources (QLD) - registered applications (i.e. those that have complied with the The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members March 2021. registration test), and agents and the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) Native Title Claimant Applications and - new and/or amended applications where the registration test is being accept no liability and give no undertakings guarantees or warranties KOWANYAMA COO KTOW N (! (! As part of the transitional provisions of the amended Native Title Act in applied, concerning the accuracy, completeness or fitness for purpose of the Determination Areas 1998, all applications were taken to have been filed in the Federal - unregistered applications (i.e. -

Aboriginal Rock Art and Dendroglyphs of Queensland's Wet Tropics

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Buhrich, Alice (2017) Art and identity: Aboriginal rock art and dendroglyphs of Queensland's Wet Tropics. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/51812/ The author has certified to JCU that they have made a reasonable effort to gain permission and acknowledge the owner of any third party copyright material included in this document. If you believe that this is not the case, please contact [email protected] and quote https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/51812/ Art and Identity: Aboriginal rock art and dendroglyphs of Queensland’s Wet Tropics Alice Buhrich BA (Hons) July 2017 Submitted as part of the research requirements for Doctor of Philosophy, College of Arts, Society and Education, James Cook University Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank the many Traditional Owners who have been my teachers, field companions and friends during this thesis journey. Alf Joyce, Steve Purcell, Willie Brim, Alwyn Lyall, Brad Grogan, Billie Brim, George Skeene, Brad Go Sam, Marita Budden, Frank Royee, Corey Boaden, Ben Purcell, Janine Gertz, Harry Gertz, Betty Cashmere, Shirley Lifu, Cedric Cashmere, Jeanette Singleton, Gavin Singleton, Gudju Gudju Fourmile and Ernie Grant, it has been a pleasure working with every one of you and I look forward to our future collaborations on rock art, carved trees and beyond. Thank you for sharing your knowledge and culture with me. This thesis would never have been completed without my team of fearless academic supervisors and mentors, most importantly Dr Shelley Greer. -

Download the Rainforest Aboriginal News (PDF, 2.3MB)

Traditional 0wner Leadership Group The Traditional Owner Leadership Group (TOLG) consists of: Kaylene Malthouse, Updates Alwyn Lyall, Tracey Heenan and Victor Maund (North Queensland Land Council Board Directors); Allison Halliday (Indigenous Director, Terrain NRM); and Phil What’s been happening Rist, Leah Talbot, Joann Schmider, John Locke, Dennis Ah Kee and Seraeah Wyles (WTMA Indigenous Advisory Committee members). in the Wet Tropics… International Women’s Day 6 March 2018 ISSUE SIX : June 2018 Wet Tropics Tour Guide Program workshops 6–7 March 2018 Celebrating Rainforest Aboriginal women: Wet Tropics Tour Guide Program NRM update field school Mandingalbay Yidinji Fire has been on the horizon lately! It’s been great to see Girringun’s TOLG’s first meeting was held 23 March, 2018. The group considered the outcomes of country 16–17 March 2018 fire program, which is supported the Rainforest Aboriginal People’s Regional Workshop at Palm Cove, 21–22 October Wet Tropics Traditional Owner by Terrain, build on last year’s 2017, and also began to develop a collaborative framework/implementation plan Leadership Group (TOLG) meeting experience. Girringun recently led for refreshing the Regional Agreement. The refresh will continue through a series 23 March 2018 their second burn, and 11 rangers of negotiations between original signatories, Traditional Owners across the Wet Cairns ECOfiesta 3 June 2018 completed their level 1 fire training. Tropics, the Authority, and the State and Commonwealth governments. The TOLG Reconciliation Week 27 May–3 June Controlled burns will also take place also aims to ensure the updated Wet Tropics Management Plan 1998 is a document 2018 in the Cooktown region over coming that appropriately recognises the rights and interests of Rainforest Aboriginal World Heritage update months, completing fire training for people, many of which have already been articulated in the Wet Tropics Regional Community Consultative Committee Welcome to the sixth Rainforest The first Traditional Owner Leadership Jabalbina and Bulmba rangers, Mamu Agreement. -

Tropics Tour Guide Handbook: Stage 1 Report

© James Cook University, 2011 Prepared by Julie Carmody, School of Business (Tourism), James Cook University, Cairns ISBN 978-1-921359-66-8 (pdf) To cite this publication: Carmody, J. (2010) Wet Tropics of Queensland World Heritage Area Tour Guide Handbook. Published by the Reef & Rainforest Research Centre Ltd., Cairns (220 pp.). Cover Photographs: Licuala Fan Palm forest – Suzanne Long Tour group – Tourism Queensland 4WD tour – Wet Tropics Management Authority Research to support this Tour Guide Handbook was funded by the Australian Government’s Marine and Tropical Sciences Research Facility, the Wet Tropics Management Authority and James Cook University. The Marine and Tropical Sciences Research Facility (MTSRF) is part of the Australian Government’s Commonwealth Environment Research Facilities programme. The MTSRF is represented in North Queensland by the Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited (RRRC). The aim of the MTSRF is to ensure the health of North Queensland’s public environmental assets – particularly the Great Barrier Reef and its catchments, tropical rainforests including the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area, and the Torres Strait – through the generation and transfer of world class research and knowledge sharing. This publication is copyright. The Copyright Act (1968) permits fair dealing for study, research, information or educational purposes subject to inclusion of a sufficient acknowledgement of the source. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. While reasonable effort has been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. -

Relisting the Cultural Values for World Heritage

Relisting the Cultural Values for World Heritage ‘Which Way Australia’s Rainforest Culture’: Relisting the Cultural Values for World Heritage Discussion paper about realising the national and international recognition of the Rainforest Aboriginal cultural values of the Wet Tropics region and World Heritage Area Compiled by Ro Hill, Ellie Bock and Petina Pert with and on behalf of the Rainforest Aboriginal Peoples and the Cultural Values Project Steering Committee March 2016 Relisting the Cultural Values for World Heritage Citation Cultural Values Project Steering Committee. (2016). Which way Australia’s rainforest culture: Relisting the cultural values for world heritage. Discussion paper about realising the national and international recognition of the Rainforest Aboriginal cultural values of the Wet Tropics region and World Heritage Area. Compiled by Ro Hill, Ellie Bock and Petina Pert with and on behalf of the Rainforest Aboriginal Peoples and the Cultural Values Project Steering Committee: Cairns, Australia. Copyright and disclaimer © Cultural Values Project Steering Committee To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of the Rainforest Aboriginal Peoples, the Committee, JCU and CSIRO. Important disclaimer Rainforest Aboriginal Peoples, the Cultural Values Project Steering Committee, JCU and CSIRO jointly advise that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based on Rainforest Aboriginal peoples, community and government sector engagement, and research. The reader is advised and needs to be aware that such information may be incomplete or unable to be used in any specific situation. -

May/June 2002 May/June 2002

arch/April 2002 May/June 2002 No.3/2002 May/June 2002 No.3/2002 The Native Title Newsletter is published on a bi-monthly basis. The newsletter includes a Contents summary of native title as reported in the News from the Native Title press. Although the summary canvasses me- Research Research Unit Unit 2 dia from around Australia, it is not intended to be an exhaustive review of de- Features velopments. NativeAn update Title onBusiness the British -Travelling Columbia Art The Native Title Newsletter also includes Treaty Process by Mark McMillan 3 Exhibition 5 contributions from people involved in native title research and processes. Views ex- YortaMaMu Yorta Canopy – CourtWalk Report 7 pressed in the contributions are those of the by Lisa Strelein 7 Ngarla Pilbara Leadership Training authors and do not necessarily reflect the CourseNative title in the news 119 views of the Australian Institute of Aborigi- nal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. NativeApplications title in the news 10 13 Notifications 14 Applications 15 Recent publications 14 NativeNotifications Title Research Unit publications 16 STOP PRESS Recent Publications 16 The Native Title Conference 2002: Outcomes and Possibilities Geraldton 3 -5 September Native Title Research Unit publications 17 Registrations close 16 August The Newsletter is now available in ELECTRONIC format. This will provide a FASTER service for you, and will make possible much greater distribution. If you would like to SUBSCRIBE to the Native Title Newsletter electronically, please send us an email on [email protected], and you will be helping us pro- vide a better service. Electronic subscription will replace the postal service, please include your postal address so we can cross check our records. -

Queensland for That Map Shows This Boundary Rather Than the Boundary As Per the Register of Native Title Databases Is Required

140°0'E 145°0'E 150°0'E Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from NNTT based on Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal Court, the determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and data sourced from Department of Resources (Qld) © The State of Queensland for that map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per the Register of Native Title databases is required. Further information is available from the Tribunals website at portion where their data has been used. Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 Topographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) 2006. The applications shown on the map include: Maritime boundaries data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) - registered applications (i.e. those that have complied with the registration test), The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members and agents and Queensland 2006. - new and/or amended applications where the registration test is being applied, the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) accept no liability and give no - unregistered applications (i.e. those that have not been accepted for registration), undertakings guarantees or warranties concerning the accuracy, completeness or As part of the transitional provisions of the amended Native Title Act in 1998, all - compensation applications. fitness for purpose of the information provided. Native Title Claimant Applications applications were taken to have been filed in the Federal Court. In return for you receiving this information you agree to release and Any changes to these applications and the filing of new applications happen through Determinations shown on the map include: indemnify the Commonwealth and third party data suppliers in respect of all claims, and Determination Areas the Federal Court.