Using Art: a Theory of Contemporary Ceramics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lisa Gralnick

Lisa Gralnick (608) 262-0189 (office) (608) 262-2049 (studio) E-mail: [email protected] Education 1980 Master of Fine Arts, State University of New York, New Paltz (Gold and Silversmithing) Major Professors: Kurt Matzdorf and Robert Ebendorf 1977 Bachelor of Fine Arts, Kent State University Major Professors: Mary Ann Scherr and James Someroski Teaching Appointments 2007- present Professor of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison 2004-2007 Associate Professor of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison 2001-2004 Assistant Professor of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1991-01 Full-Time Faculty, Parsons School of Design, New York, NY (Chair of Metals /Jewelry Design Program) 1982-83 Visiting Assistant Professor, Head of Jewelry Dept., Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, Halifax 1980-81 Visiting Assistant Professor, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio Grants, Awards, Fellowships, and Honors 2012 Faculty Development Grant, University of Wisconsin-Madison 2012 Kellett Mid-Career Award, University of Wisconsin-Madison 2010 Wisconsin Arts Board Individual Artist Fellowship 2010 Graduate School Faculty Research Grant, University of Wisconsin- Madison 2009 Rotasa Foundation Grant to fund exhibition catalog at Bellevue Arts Museum 2009 Graduate School Faculty Research Grant, University of Wisconsin- Madison 2008 Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Oral Interview (available online) 2008 Graduate School Faculty Research Grant, University of Wisconsin- Madison 2007 Graduate School Faculty Research Grant, University of Wisconsin- Madison -

Exhibit Catalog (PDF)

Mastery in Jewelry & Metals: Irresistible Offerings! Gail M. Brown, Curator Mastery in Jewelry & Metals: Irresistible Offerings! Gail M. Brown, Curator Participating Artists Julia Barello Mary Lee Hu Harriete Estel Berman Michael Jerry Elizabeth Brim Robin Kranitzky & Kim Overstreet Doug Bucci Rebecca Laskin Kathy Buszkiewicz Keith Lewis Harlan W. Butt Charles Lewton-Brain Chunghi Choo Linda MacNeil Sharon Church John Marshall John Cogswell Bruce Metcalf Chris Darway Eleanor Moty Jack DaSilva Tom Muir Marilyn DaSilva Harold O'Connor Robert Ebendorf Komelia Okim Sandra Enterline Albert Paley Fred Fenster Beverly Penn Arline Fisch Suzan Rezac Pat Flynn Stephen Saracino David C. Freda Hiroko Sato-Pijanowski Don Friedlich Sondra Sherman John G. Garrett Helen Shirk Lisa Gralnick Lin Stanionis Gary S. Griffin Billie Theide Laurie Hall Rachelle Thiewes Susan H. Hamlet Linda Threadgill Douglas Harling What IS Mastery? A singular idea, a function, a symbol becomes a concept, a series, a marker- a recognizable visual attitude and identifiable vocabulary which grows into an observation, a continuum, an unforgettable commentary. Risk taking. Alone and juxtaposed….so many ideas inviting exploration. Contrasting moods and attitudes, stimuli and emotional temperatures. Subtle or bold. Serene or exuberant. Pithy observations of the natural and WHAT is Mastery? manmade worlds. The languages of beauty, aesthetics and art. Observation and commentary. Values and conscience. Excess and dearth, The pursuit and attainment, achievement of purpose, knowledge, appreciation and awareness. Heavy moods and childlike insouciance. sustained accomplishment and excellence. The creation of irrepressible, Wisdom and wit. Humor and critique. Reality and fantasy. Figuration important studio jewelry and significant metal work: unique, expressive, and abstraction. -

Exuberance of Color V3.Indd

TANSEY CONTEMPORARY Presents AN EXUBERANCE OF COLOR In Studio Jewelry Curated by Gail M. Brown www.tanseycontemporary.com 1 Contents AN EXUBERANCE OF COLOR In Studio Jewelry curated by Gail M.Brown Contents Julia Barello ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Harriete Estel Berman...................................................................................................................... 9 Jessica Calderwood........................................................................................................................ 12 Arline Fisch ....................................................................................................................................... 16 Donald Friedlich............................................................................................................................... 20 Rebekah Laskin................................................................................................................................ 26 Amy Lemaire.................................................................................................................................... 30 Karen Thuesen Massaro................................................................................................................... 36 Bruce Metcalf................................................................................................................................... 40 Mike & Maaike................................................................................................................................. -

Acknowledgments from the Authors

Makers: A History of American Studio Craft, by Janet Koplos and Bruce Metcalf, published by University of North Carolina Press. Please note that this document provides a complete list of acknowledgments by the authors. The textbook itself contains a somewhat shortened list to accommodate design and space constraints. Acknowledgments from the Authors The Craft-Camarata Frederick Hürten Rhead established a pottery in Santa Barbara in 1914 that was formally named Rhead Pottery but was known as the Pottery of the Camarata (“friends” in Italian). It was probably connected with the Gift Shop of the Craft-Camarata located in Santa Barbara at that time. Like his pottery, this book is not an individual achievement. It required the contributions of friends of the field, some personally known to the authors, but many not, who contributed time, information and funds to the cause. Our funders: Windgate Charitable Foundation / The National Endowment for the Arts / Rotasa Foundation / Edward C. Johnson Fund, Fidelity Foundation / Furthermore: a program of the J. M. Kaplan Fund / The Greenberg Foundation / The Karma Foundation / Grainer Family Foundation / American Craft Council / Collectors of Wood Art / Friends of Fiber Art International / Society of North American Goldsmiths / The Wood Turning Center / John and Robyn Horn / Dorothy and George Saxe / Terri F. Moritz / David and Ruth Waterbury / Sue Bass, Andora Gallery / Ken and JoAnn Edwards / Dewey Garrett / and Jacques Vesery. The people at the Center for Craft, Creativity and Design in Hendersonville, N.C., administrators of the book project: Dian Magie, Executive Director / Stoney Lamar / Katie Lee / Terri Gibson / Constance Humphries. Also Kristen Watts, who managed the images, and Chuck Grench of the University of North Carolina Press. -

ANNOUNCING Heatguns, to Makelightweight, and Strong, Colorful Material (Polyesther Fi Be Covered/Glued with High-Tech Modelairplane for Useinearrings, Orpendants

See p3 for details ANNOUNCING METAL ARTS 2017 SOCIETY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA January / February MATRIX JEWELRY WORKSHOP - Robert K. Liu February 18th, 2016 8am – 5pm interesting jewelry. This technique is well suited to Robert K. Liu he is co- make earrings, symmetrical or asymmetrical. Essen- editor of Ornament and tially, your imagination and skill are the limitations of has written extensively on the forms you can make. For a one-day workshop, it ancient, ethnographic and is necessary to have soldering and simple handtool contemporary jewelry and skills. personal adornment since 1974. Over the past four ddecades, he has lectured eextensively in the US, as willill learn l to use brass b wire i or bronze b StudentsSt d t wwell as the UK and PRC rod to fabricate matrix/matrices for use as pen- aand given workshops on dants, earrings or other jewelry components. jjewelry photography, Simple handtools or mandrels will be used to shape making bamboo jewelry or matrix jewelry and has the wire or rodforms, then solder them. Participants recently published The Photography of Personal will learn how to handform wire/rod foundations AAdornment. He is also the author of Collectible for use in earrings, or pendants. These matrices will Beads, and has written over 700 articles or other be covered/glued with high-tech model airplane publications, on personal adornment, technology material (polyesther fi lms), then heatshrunk with aand science. heatguns, to make lightweight, strong, colorful and Cost: $105 for MASSC Members - $125 for non members Materials Fee: $10 Location: Irvine This workshop will be fi lled via the MASSC lottery system with MASSC members receiving priority. -

Donald Friedlich Curriculum Vitae

Donald Friedlich Curriculum Vitae 2712 Marshall Parkway Phone: 608 280-9151 Madison, WI 53713 Mobile: 608 217-3581 [email protected] DonaldFriedlich.com EDUCATION 1982 Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, Rhode Island B.F.A. Jewelry/Metalsmithing 1975-79 University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont MUSEUM AND MAJOR PRIVATE COLLECTIONS Victoria and Albert Museum, London, England Smithsonian American Art Museum, Renwick Gallery, Washington, DC Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Boston, Massachusetts Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, New York Schmuckmuseum, Pforzheim, Germany Museum of Fine Arts Houston, Houston, Texas Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal, Canada Museum of the Arts and Design, New York, New York Yale Art Museum, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut Newark Museum of Art, Newark, New Jersey Mint Museum of Craft and Design, Charlotte, North Carolina Racine Art Museum, Racine, Wisconsin Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art, SUNY New Paltz, New Paltz, New York Helen Drutt, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Garth Clark and Mark Del Vecchio, Santa Fe, New Mexico Daphne Farago, Little Compton, Rhode Island Robert Phannebacker, Lancaster, Pennsylvania PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES 1999-2001 President, Society of North American Goldsmiths 1998 President Elect, Society of North American Goldsmiths 2002 Past President, Society of North American Goldsmiths 1999-2019 SOFA/SNAG Lecture Series, Selected speakers and managed the program 2003-08 -

Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory Thesis Ken Price & the Egg Series Phenomenal Transgressions in Post-War Cerami

Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory Thesis Ken Price & The Egg Series Phenomenal Transgressions in Post-war Ceramics Maxwell Mustardo Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory, School of Art and Design Division of Art History New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University Alfred, New York 2017 Maxwell Amadeo Kennedy Mustardo, BS Mary Drach McInnes, Thesis Advisor Kenneth Martin Price (1935-2012) was a key protagonist in moving ceramics into the avant-garde realm during the 1960s. At this time, Price made his first major contribution to the expanding field of ceramic sculpture with his Egg series. This series represents a significant breakthrough in ceramic sculpture by transgressing the traditions and processes of mid-century ceramics. Post-war ceramic conventions were generally dominated by the craft theories of the folk pottery movement. During the 1950s, Peter Voulkos and others had begun making interventions aimed at broadening ceramic practices, but relied upon the techniques and processes of the very practices they were challenging. Price’s Egg series, which he made while in league with Los Angeles’ revolutionary Ferus Gallery, pushed Voulkos’ explorations of clay beyond the limitations of ceramic traditions and processes. My thesis offers critical and contextual analyses of the Egg series by interrogating its significance to broader trends in American post-war ceramics. By the time of Price’s death in 2012, his prolific fifty-year career solidified him as one of the key protagonists of 20th century ceramic art. Price was born in 1935 in Los Angeles and studied at the University of Southern California, the Otis Institute, and Alfred University during the 1950s for his undergraduate and graduate studies. -

7 from Describing It As an Aesthetic Rejection of Modernism Or A

7 from describing it as an aesthetic rejection of modernism or a disbelief in “modern myths of progress and mastery” to a matter of the “politics of interpretation.”26 Given the varied understandings of postmodernism, it becomes necessary to outline a somewhat arbitrary definition for postmodernism in the context of studio furniture. Literally, it means that which came after the modern. Yet, because literature, film, art and architecture each found different ways of expressing modernity and its anxieties and celebrations, the various responses also took a range of forms. At the same time, some characteristics and ideas of modernism and postmodernism carry across different fields and offer a useful understanding for this discussion. The Utopian project of modernism strove to create a better, more peaceful world; poet Ezra Pound’s proclamation “make it new” offered one solution. Architects and designers turned to a stripped down modern style, the austerity of which privileged no one nation or culture over another and avoided referencing the past.27 With the desire to make new artistic creations unrelated to the past came a push for originality. In modern art, artists adhered to an idea of autonomy—that a painting or sculpture could stand alone, “existing without reference to or influence from anything else.”28 In painting and sculpture this involved abstraction and focusing on and emphasizing the particular essential qualities that make a painting a painting—its two-dimensionality, or flatness— and a sculpture a sculpture—its three-dimensionality, or form. In architecture and design, this formalism and desire for purity manifested in a focus on function. -

43RD Annual SNAG Conference

2014 SNAG Conference Program 43RD Annual SNAG Conference In partnership with: WELCOME TO MINN-EH-SOH-TAH! From Grains to Gold We are so happy to have you join us and thrilled to host the 43rd annual Society 2014 Co-chairs of North American Goldsmiths (SNAG) Conference "From Grains to Gold”. Here in “The City of Lakes”, you might be offered a pop or hotdish and it’s guaranteed someone will want to talk about the weather; just smile, nod and you’ll fit right in. We hope our “Minnesota Nice” reputation lives up to its name. In 1970, the very first SNAG Conference was held right here in the Twin Cities and we couldn’t be more honored to see it come full circle; reminiscing about the past as we forge ahead to the future. We feel that Minneapolis, with its booming and Dominique Bereiter vibrant arts community, is the perfect backdrop and host city to welcome creative people like yourselves, for the 2014 conference. Throughout the conference, you will have the opportunity to get out into the Twin Cities to explore and tour converted warehouse buildings that now house artists, makers, craftsmen, musicians, and designers; peruse nationally acclaimed local galleries in fine craft and modern art; and hear from a wide array of speakers from the US and abroad. In addition to the main stage presentations, we have created smaller, Face-to-Face, conference experiences with our presenters, Emily Johnson more networking opportunities and sessions to create meaningful and lasting relationships amongst the SNAG membership. Our goal is to educate, inspire, and connect with each other, to grow and uplift the SNAG community as a whole. -

The Wood Turning Center Is a Non-Profit Arts Institution Dedicated

Chronological List of Exhibitions & Publications The Center for Art in Wood 141 N. 3rd Street | Philadelphia, PA 19106 | 215-923-8000 Exhibitions in italics were accompanied by publications. Title of exhibition catalogue is listed with its details. 2017 CRISS CROSS: ROBYN HORN / BRIAN DICKERSON, October 27, 2017 – January 18, 2018, The Center for Art in Wood. Curator, Miriam Seidel. Two artists who use wood as a primary material, but whose work has emerged out of different traditions, set their work in conversation here. Both have created new work for this exhibition in response to the other’s practice that illuminates the intersections of texture and finish, paint versus natural surface, sculpture and painting, craft and fine art. Exhibiting artists: Robyn Horn, Brian Dickerson 2017 Bob Stocksdale International Excellence in Wood Award, October 27, 2017 – January 18, 2018, The Center for Art in Wood Supported by an anonymous donor, this $1,000 award is presented annually to an emerging or mid-career artist whose work, like Stocksdale’s, unites quality of craftsmanship and respect for materials. Dean Pulver, USA, is the 2017 recipient. In recognizing his talent and vision, Albert LeCoff commented that Dean “creates pieces that are raw and honest, expressing the perfection in imperfection as monuments to our existence.” 2017 allTURNatives: Form + Spirit 2017, August 4 – October 14, 2017, The Center for Art in Wood. Celebrating the 22nd year of the International Turning Exchange Residency (ITE) program, the Center is proud to host the international artists, photojournalist and scholar who worked together for 2 months at the UArts in Philadelphia and explored new directions in their work. -

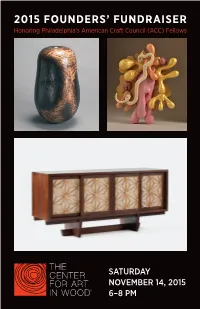

2015 Founders' Fundraiser

2015 FOUNDERS’ FUNDRAISER Honoring Philadelphia’s American Craft Council (ACC) Fellows SATURDAY NOVEMBER 14, 2015 6–8 PM BOARD OF TRUSTEES Richard R. Goldberg, President John J. Dziedzina, 1st Vice President Alan D. Keiser, Esq, 2nd Vice President Lee Bender, Secretary Leonard J. Kreppel, Treasurer Suzanne Kahn Tim Kochman Alan LeCoff Albert LeCoff, Executive Director Gina Principato The Board of Trustees is pleased to recognize the Philadelphia area ACC Fellows for their astounding work as artists and this opportunity to exhibit their work at the Center. Mission: The Center for Art in Wood will continue to be the preeminent arts and education organization advancing the growth, awareness, appreciation and promotion of artists and the creation and design of art in wood and wood in combination with other materials. 1 Michael Hurwitz. First Bowl, 1981. Collection of Bernice Wollman 2015 FOUNDERS’ FUNDRAISER Honoring Philadelphia’s American Craft Council (ACC) Fellows Saturday, November 14, 2015 6–8 PM Master of Ceremonies | Richard R. Goldberg PRESENTATIONS BY Albert LeCoff Co-Founder and Executive Director Helen W. Drutt English Keynote Speaker 3 Salute To Our Fellows This event is the third Annual Founders’ Fundraiser where The Center for Art In Wood pays tribute to important artists and contributors to the field of wood art. Our first event honored our founders, Albert and Alan LeCoff. The second honoree was Ron Fleming, one of the most significant wood artists of our time and one who was highly influential in the early development of the Center. This event recognizes five artists in wood who have received one of the highest honors bestowed on craft artists: they have been named Fellows of the American Craft Council. -

Furniture That Winks: Wit and Conversation In

Furniture that Winks: Wit and Conversation in Postmodern Studio Furniture, 1979-1989 Julia Elizabeth T. Hood Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the History of Decorative Arts Masters Program in the History of Decorative Arts The Smithsonian Associates and Corcoran College of Art + Design 2011 This work was supported by a Craft Research Fund grant from The Center for Craft, Creativity and Design, a center of UNC Asheville. © 2011 Julia Elizabeth T. Hood All Rights Reserved Table of Contents List of Illustrations ii Acknowledgements iv Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Rejecting Modernism in Craft Furniture 13 Chapter 2: New Purpose for Furniture: Communicating Ideas 40 Chapter 3: A Return to History with Irony: Historicism in Craft Furniture 55 Chapter 4: What is Real?: Perception and Reality, Simulacra and Illusion 72 Conclusion 89 Notes 93 Selected Bibliography 119 Illustrations 123 i List of Illustrations* Figure 1. Garry Knox Bennet, Nail Cabinet, 1979. ....................................................... 123 Figure 2. Nail Cabinet door frame illustration. .............................................................. 123 Figure 3. Trade illustration of a Katana bull-nose router bit.......................................... 123 Figure 4. James Krenov, Jewelry Box, 1969. ............................................................... 123 Figure 5. Detail of Figure 4. .......................................................................................... 123 Figure 6. Tommy Simpson, Man