An Economic and Social Analysis of Childcare in Winnipeg Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of the Winnipeg Centre, RASC 1911-77

A HISTORY OF THE WINNIPEG CENTRE, ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY OF CANADA 1911 -1 9 7 7 EDITOR: Phyllis Belfield ASSISTANT EDITORS: Ella Dack Patricia Berezowski CONTENTS pag e Introduction Chapter 1 The W innipeg Centre, RASC. 1911-1977 2 Chapter 2 "On Observing Heavenly Bodies" 7 Chapter 3 Project Moonwatch 11 Chapter 4 From Telescope to Observatory 14 Chapter 5 The Book Corner 18 Chapter 6 Minutes And Moments 21 Chapter 7 Outreach 23 Chapter 8 To Capture An Image 26 Chapter 9 The Newsletter 28 Chapter 10 R.A.S.C. Awards 31 Chapter 11 An Amateur's Observatory 34 Chapter 12 Solar Eclipses 36 Chapter 13 Personal Anecdotes 44 Chapter 14 A Centre In The Making 58 Chapter 15 The Centre's Mosaic 60 Appendix 1 List of Officers of W innipeg Centre 63 Appendix 11 List of Photographs 69 INTRODUCTION A word about the creation of this book. It was con ceived in 1976, underwent a gestation period of a few months until the decision was made to have the history written by a group of members rather than one individual. How long should the history be? It could fill many hundreds of pages, but time and money would not permit the compiling of a lengthy book. Condensing sixty-six years into about as many pages was quite a challenge. Undoubtedly some of our members will be disappointed because events they considered unforgettable have not been mentioned, but it is not possible to refer to every single event, just as it is not possible to name every person who has participated in the Centre's activities since the day of inception. -

Canada Gazette, Part I

EXTRA Vol. 153, No. 12 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 153, no 12 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 14, 2019 OTTAWA, LE JEUDI 14 NOVEMBRE 2019 OFFICE OF THE CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER BUREAU DU DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members elected at the 43rd general Rapport de député(e)s élu(e)s à la 43e élection election générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Can- Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’ar- ada Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, ticle 317 de la Loi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, have been received of the election of Members to serve in dans l’ordre ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élec- the House of Commons of Canada for the following elec- tion de député(e)s à la Chambre des communes du Canada toral districts: pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral District Member Circonscription Député(e) Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Matapédia Kristina Michaud Matapédia Kristina Michaud La Prairie Alain Therrien La Prairie Alain Therrien LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Burnaby South Jagmeet Singh Burnaby-Sud Jagmeet Singh Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke Randall Garrison Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke -

Endowment Funds 1921-2020 the Winnipeg Foundation September 30, 2020 (Pages 12-43 from Highlights from the Winnipeg Foundation’S 2020 Year)

Endowment Funds 1921-2020 The Winnipeg Foundation September 30, 2020 (pages 12-43 from Highlights from The Winnipeg Foundation’s 2020 year) Note: If you’d like to search this document for a specific fund, please follow these instructions: 1. Press Ctrl+F OR click on the magnifying glass icon (). 2. Enter all or a portion of the fund name. 3. Click Next. ENDOWMENT FUNDS 1921 - 2020 Celebrating the generous donors who give through The Winnipeg Foundation As we start our centennial year we want to sincerely thank and acknowledge the decades of donors from all walks of life who have invested in our community through The Winnipeg Foundation. It is only because of their foresight, commitment, and love of community that we can pursue our vision of “a Winnipeg where community life flourishes for all.” The pages ahead contain a list of endowment funds created at The Winnipeg Foundation since we began back in 1921. The list is organized alphabetically, with some sub-fund listings combined with the main funds they are connected to. We’ve made every effort to ensure the list is accurate and complete as of fiscal year-end 2020 (Sept. 30, 2020). Please advise The Foundation of any errors or omissions. Thank you to all our donors who generously support our community by creating endowed funds, supporting these funds through gifts, and to those who have remembered The Foundation in their estate plans. For Good. Forever. Mr. W.F. Alloway - Founder’s First Gift Maurice Louis Achet Fund The Widow’s Mite Robert and Agnes Ackland Memorial Fund Mr. -

2016 Tax Year

Table 1a - Federal Electoral District Statistics for All Returns - 2016 Tax Year Total Income Net Income Taxable Income FED ID Federal Electoral Districts Total ($000) ($000) ($000) PR 10 Newfoundland and Labrador 10001 Avalon 72,030 3,425,814 3,168,392 3,060,218 10002 Bonavista--Burin--Trinity 64,920 2,453,784 2,303,218 2,185,134 10003 Coast of Bays--Central--Notre Dame 65,130 2,458,068 2,286,474 2,173,178 10004 Labrador 20,830 1,169,248 1,089,412 992,898 10005 Long Range Mountains 77,250 2,914,423 2,714,495 2,579,982 10006 St. John's East 66,670 3,668,269 3,345,338 3,268,761 10007 St. John's South--Mount Pearl 66,270 3,086,318 2,836,073 2,739,070 TOTAL 433,100 19,175,924 17,743,402 16,999,241 Table 1a - Federal Electoral District Statistics for All Returns - 2016 Tax Year Total Income Net Income Taxable Income FED ID Federal Electoral Districts Total ($000) ($000) ($000) PR 11 Prince Edward Island 11001 Cardigan 29,970 1,237,610 1,140,059 1,103,647 11002 Charlottetown 29,650 1,192,487 1,098,089 1,060,050 11003 Egmont 29,310 1,079,972 1,003,318 959,122 11004 Malpeque 28,880 1,194,581 1,098,945 1,059,173 TOTAL 117,810 4,704,650 4,340,412 4,181,993 Table 1a - Federal Electoral District Statistics for All Returns - 2016 Tax Year Total Income Net Income Taxable Income FED ID Federal Electoral Districts Total ($000) ($000) ($000) PR 12 Nova Scotia 12001 Cape Breton--Canso 59,950 2,234,171 2,074,721 1,980,399 12002 Central Nova 60,040 2,370,409 2,190,341 2,106,315 12003 Cumberland--Colchester 66,070 2,418,184 2,242,671 2,156,801 12004 Dartmouth--Cole Harbour 74,670 3,360,261 3,056,811 2,990,209 12005 Halifax 72,440 3,582,762 3,290,294 3,209,508 12006 Halifax West 75,220 3,719,510 3,389,142 3,331,581 12007 Kings--Hants 67,220 2,632,211 2,429,195 2,353,692 12008 Sackville--Preston--Chezzetcook 69,410 3,231,041 2,949,533 2,896,662 12009 South Shore--St. -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

ELECTORAL DISTRICTS Proposal for the Province of Manitoba

ELECTORAL DISTRICTS Proposal for the Province of Manitoba Published pursuant to the Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act Table of Contents Part I — Preamble ........................................................................................................................... 3 Part II — Notice of Sittings for the Hearing of Representations .................................................. 10 Part III — Rules ............................................................................................................................ 11 Schedule — Maps, Proposed Boundaries and Names of Electoral Districts ................................ 14 2 Federal Electoral Boundaries Commission for the Province of Manitoba Proposal Part I — Preamble Introduction Each decade, after the decennial census is completed, a key democratic exercise called electoral redistribution takes place. Redistribution is meant to reflect population growth and the territorial shifts in population both among and within provinces. There are two steps in the redistribution process. The first step involves a recalculation of the number of seats in the House of Commons given to each province based on new population estimates and a complex formula contained in the Constitution. After the current redistribution, the number of seats in the House of Commons will have increased from 308 to 338. Four provinces—Alberta, British Columbia, Quebec and Ontario—will gain seats. Along with five other provinces, Manitoba is retaining the same number of seats (14) that it had before -

Municipal Officials Directory 2021

MANITOBA MUNICIPAL RELATIONS Municipal Officials Directory 21 Last updated: September 23, 2021 Email updates: [email protected] MINISTER OF MUNICIPAL RELATIONS Room 317 Legislative Building Winnipeg, Manitoba CANADA R3C 0V8 ,DPSOHDVHGWRSUHVHQWWKHXSGDWHGRQOLQHGRZQORDGDEOH0XQLFLSDO2IILFLDOV'LUHFWRU\7KLV IRUPDWSURYLGHVDOOXVHUVZLWKFRQWLQXDOO\XSGDWHGDFFXUDWHDQGUHOLDEOHLQIRUPDWLRQ$FRS\ FDQEHGRZQORDGHGIURPWKH3URYLQFH¶VZHEVLWHDWWKHIROORZLQJDGGUHVV KWWSZZZJRYPEFDLDFRQWDFWXVSXEVPRGSGI 7KH0XQLFLSDO2IILFLDOV'LUHFWRU\FRQWDLQVFRPSUHKHQVLYHFRQWDFWLQIRUPDWLRQIRUDOORI 0DQLWRED¶VPXQLFLSDOLWLHV,WSURYLGHVQDPHVRIDOOFRXQFLOPHPEHUVDQGFKLHI DGPLQLVWUDWLYHRIILFHUVWKHVFKHGXOHRIUHJXODUFRXQFLOPHHWLQJVDQGSRSXODWLRQV,WDOVR SURYLGHVWKHQDPHVDQGFRQWDFWLQIRUPDWLRQRIPXQLFLSDORUJDQL]DWLRQV0DQLWRED([HFXWLYH &RXQFLO0HPEHUVDQG0HPEHUVRIWKH/HJLVODWLYH$VVHPEO\RIILFLDOVRI0DQLWRED0XQLFLSDO 5HODWLRQVDQGRWKHUNH\SURYLQFLDOGHSDUWPHQWV ,HQFRXUDJH\RXWRFRQWDFWSURYLQFLDORIILFLDOVLI\RXKDYHDQ\TXHVWLRQVRUUHTXLUH LQIRUPDWLRQDERXWSURYLQFLDOSURJUDPVDQGVHUYLFHV ,ORRNIRUZDUGWRZRUNLQJLQSDUWQHUVKLSZLWKDOOPXQLFLSDOFRXQFLOVDQGPXQLFLSDO RUJDQL]DWLRQVDVZHZRUNWRJHWKHUWREXLOGVWURQJYLEUDQWDQGSURVSHURXVFRPPXQLWLHV DFURVV0DQLWRED +RQRXUDEOHDerek Johnson 0LQLVWHU TABLE OF CONTENTS MANITOBA EXECUTIVE COUNCIL IN ORDER OF PRECEDENCE ............................. 2 PROVINCE OF MANITOBA – DEPUTY MINISTERS ..................................................... 5 MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY ............................................................ 7 MUNICIPAL RELATIONS .............................................................................................. -

Divided Prairie City Summary

summary the divided prairie city Income Inequality Among Winnipeg’s Neighbourhoods, 1970–2010 Edited by Jino Distasio and Andrew Kaufman Tom Carter, Robert Galston, Sarah Leeson-Klym, Christopher Leo, Brian Lorch, Mike Maunder, Evelyn Peters, Brendan Reimer, Martin Sandhurst, and Gina Sylvestre. This handout summarizes findings from The Divided Prairie City released by the Institute of Urban Studies Incomes are growing less (IUS) at The University of Winnipeg. 4 equal in Winnipeg. The IUS is part of a Neighbourhood Change Research Partner- ship (NCRP) funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities From 1970 to 2010, income inequality in Winnipeg grew by 20%. Research Council of Canada (SSHRC). Led by the Cities Cen- • 40% of Winnipeg’s neighbourhoods experienced declining tre at the University of Toronto, this study examines income incomes from 1980 to 2010—only 16% of Winnipeg’s neigh- inequality in Halifax, Montreal, Toronto, Hamilton, Winnipeg, bourhoods experienced increasing incomes. Calgary, and Vancouver. • Income inequality has not grown in Winnipeg to the same extent that it has in Toronto, Calgary, or Vancouver. Instead, Winnipeg resembles cities like Edmonton and Halifax because Income inequality is of lower concentrations of ultra high-income individuals. growing in Canada. Middle-income neighbour- 1 hoods are disappearing. Canadians believe that we live in a middle-class country, yet research 5 points to a growing income gap bet ween rich and poor neighbour- • From 1980 to 2010, one quarter of Winnipeg’s middle and up- hoods while the middle-income group shrinks. per middle-income neighbourhoods saw incomes decline to below average amounts. Incomes grew in only 13% of mid- Fourteen per cent of all income in Canada is now received by dle-income areas to above-average levels. -

5G Cell “Towers” in Winnipeg Neighbourhoods No Radiation Without Consultation

5G Winnipeg Awareness 3rd 5G CALL TO ACTION, 6 June 2020 TO: Mayor Bowman and City Councillors Province of Manitoba Manitoba Hydro Government of Canada ------------- No 4G/ 5G Cell “towers” in Winnipeg Neighbourhoods No Radiation without Consultation June 6, 2020 To all Winnipeggers and friends of Winnipeggers concerned about wireless 5G rollout, especially the installations of all sizes of cellular network antennas close to our homes CITY OF WINNIPEG The process for the City of Winnipeg to begin permitting of small cell antennas is underway. At least 3,400 small 4G/5G antennas and perhaps more than 7,000, many in our neighbourhoods. On lamp posts, hydro poles, traffic lights, sides and atop buildings. At least one on every block. Emitting 4G LTE 24/7 and then adding 5G when the technology is ready. POSSIBLE ACTIONS: 1. For the next Innovation, Economic and Development (IED) Standing Committee meeting -perhaps Monday, June 15th: • Delegate (=present) via phone, Skype or Zoom and/or submit a written report. Contact the City Clerk at https://www.winnipeg.ca/shared/htmlsnippets/MailForm.asp?Recipient=CityClerks&Title=DMIS%20Contact%2 0Form&Subjects=Feedback Watch to see when the next IED meeting will be and whether “small cells” are on the agenda: http://clkapps.winnipeg.ca/dmis/DocSearch.asp?CommitteeType=ASD&DocumentType=A • Send emails to Mayor Bowman and each City of Winnipeg Councillor (not just yours) - the more, the better (contact information below) 1/4 A SUGGESTED MESSAGE: Mention that you are a stakeholder, too. Just as the telecommunications providers have a voice, so should we. -

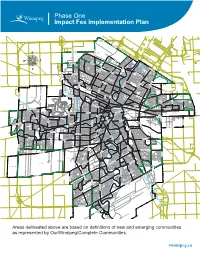

Impact Fee Implementation Plan

Phase One Impact Fee Implementation Plan ROSSER-OLD KILDONAN AMBER TRAILS RIVERBEND LEILA NORTH WEST KILDONAN INDUSTRIAL MANDALAY WEST RIVERGROVE A L L A TEMPLETON-SINCLAIR H L A NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL INKSTER GARDENS THE MAPLES V LEILA-McPHILLIPS TRIANGLE RIVER EAST MARGARET PARK KILDONAN PARK GARDEN CITY SPRINGFIELD NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL PARK TYNDALL PARK JEFFERSON ROSSMERE-A KILDONAN DRIVE KIL-CONA PARK MYNARSKI SEVEN OAKS ROBERTSON McLEOD INDUSTRIAL OAK POINT HIGHWAY BURROWS-KEEWATIN SPRINGFIELD SOUTH NORTH TRANSCONA YARDS SHAUGHNESSY PARK INKSTER-FARADAY ROSSMERE-B BURROWS CENTRAL ST. JOHN'S LUXTON OMAND'S CREEK INDUSTRIAL WESTON SHOPS MUNROE WEST VALLEY GARDENS GRASSIE BROOKLANDS ST. JOHN'S PARK EAGLEMERE WILLIAM WHYTE DUFFERIN WESTON GLENELM GRIFFIN TRANSCONA NORTH SASKATCHEWAN NORTH DUFFERIN INDUSTRIAL CHALMERS MUNROE EAST MEADOWS PACIFIC INDUSTRIAL LORD SELKIRK PARK G N LOGAN-C.P.R. I S S NORTH POINT DOUGLAS TALBOT-GREY O R C PEGUIS N A WEST ALEXANDER N RADISSON O KILDARE-REDONDA D EAST ELMWOOD L CENTENNIAL I ST. JAMES INDUSTRIAL SOUTH POINT DOUGLAS K AIRPORT CHINA TOWN C IVIC CANTERBURY PARK SARGENT PARK CE TYNE-TEES KERN PARK NT VICTORIA WEST RE DANIEL McINTYRE EXCHANGE DISTRICT NORTH ST. BONIFACE REGENT MELROSE CENTRAL PARK SPENCE PORTAGE & MAIN MURRAY INDUSTRIAL PARK E TISSOT LLIC E-E TAG MISSION GARDENS POR TRANSCONA YARDS HERITAGE PARK COLONY SOUTH PORTAGE MISSION INDUSTRIAL THE FORKS DUGALD CRESTVIEW ST. MATTHEWS MINTO CENTRAL ST. BONIFACE BUCHANAN JAMESWOOD POLO PARK BROADWAY-ASSINIBOINE KENSINGTON LEGISLATURE DUFRESNE HOLDEN WEST BROADWAY KING EDWARD STURGEON CREEK BOOTH ASSINIBOIA DOWNS DEER LODGE WOLSELEY RIVER-OSBORNE TRANSCONA SOUTH ROSLYN SILVER HEIGHTS WEST WOLSELEY A NORWOOD EAST STOCK YARDS ST. -

2015 Report on Park Assets

Appendix A 2015 Report on Park Assets Asset Management Branch Parks and Open Space Division Public Works Department Table of Contents Summary of Parks, Assets and Asset Condition by Ward Charleswood-Tuxedo-Whyte Ridge Ward ................................................................................................... 1 Daniel McIntyre Ward .................................................................................................................................. 9 Elmwood – East Kildonan Ward ................................................................................................................. 16 Fort Rouge – East Fort Garry Ward ............................................................................................................ 24 Mynarski Ward ........................................................................................................................................... 32 North Kildonan Ward ................................................................................................................................. 40 Old Kildonan Ward ..................................................................................................................................... 48 Point Douglas Ward.................................................................................................................................... 56 River Heights – Fort Garry Ward ................................................................................................................ 64 South Winnipeg – St. Norbert -

Olga Dyck Regehr

F.ROM REFUGEE TO SUBURBANITE: THE SURVIVAL AND ACCULTURATION OF NORTH KILDONAN MEI\NONITE IMMIGRANT WOMEN, 1927-1947 by OLGA DYCK REGEHR A Thesis Submitted to the Facuþ of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF'ARTS Department of History University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba August,2006 TITE T]NIVERSITY OF MANITOBA FACT]LTY OF GRADUATE STIJDIES coPYRrc'riå**rrrro* From Refugee to Suburbanite: The Survival and Acculturation of North Kildonan Mennonite Immigrant Women, 1927 -1947 BY Olga Regehr A ThesisÆracticum submitted to the ['aculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the degree OF MASTER OF ARTS Olga Regehr @ 2006 Permission has been granted to the Library of the University of Manitoba to lend or sell copies of this thesis/practicum, to the National Library of Canada to microfilm this thesis and to lend or sell copies of the filn, and to University Microfilms Inc. to publish an abstract of this thesisþracticum. This reproduction or copy of this thesis has been made available by authority of the copyright owner solely for the purpose of private study and research, and may only be reproduced and copied as permitted by copyright laws or with express written authorizatÍon from the copyright owner. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract. ll1 Acknowledgements lV Introduøion Chapter 1: Historical Background: From Ukrainian Colony to Canadian Suburbs...26 Chapter 2: The Early Days in North Kildonan 47 Chapter 3: Social Support Networks Among Immigrant Women: The 65 Chapter 4: Designs of Transition: Houses and Clothes 89 Chapter 5: Food Ways: ANexus of Acculturation.