WOMEN of RED RIVER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Go…To the Waterfront, Represents Winnipeg’S 20 Year Downtown Waterfront Vision

to the Waterfront DRAFT Go…to the Waterfront, represents Winnipeg’s 20 year downtown waterfront vision. It has been inspired by Our Winnipeg, the official development and sustainable 25-year vision for the entire city. This vision document for the to the downtown Winnipeg waterfront is completely aligned with the Complete Communities strategy of Our Winnipeg. Go…to the Waterfront provides Waterfront compelling ideas for completing existing communities by building on existing assets, including natural features such as the rivers, flora and fauna. Building upon the principles of Complete Communities, Go…to the Waterfront strives to strengthen and connect neighbourhoods with safe and accessible linear park systems and active transportation networks to each other and the downtown. The vision supports public transit to and within downtown and ensures that the river system is incorporated into the plan through all seasons. As a city for all seasons, active, healthy lifestyles 2 waterfront winnipeg... a 20 year vision draft are a focus by promoting a broad spectrum of “quality of life” infrastructure along the city’s opportunities for social engagement. Sustainability waterfront will be realized through the inclusion of COMPLETE COMMUNITIES is also a core principle, as the vision is based on economic development opportunities identified in the desire to manage our green corridors along this waterfront vision. A number of development our streets and riverbank, expand ecological opportunities are suggested, both private and networks and linkages and ensure public access public, including specific ideas for new businesses, to our riverbanks and forests. Finally, this vision infill residential projects, as well as commercial supports development: mixed use, waterfront living, and mixed use projects. -

Is the Assiniboine Zoo Free on Canada Day

Is the assiniboine zoo free on canada day click here to download Celebrate our nation's birthday on July 1 at the Canad Inns Picinic in the Park. Enjoy live music and entertainment at the Lyric Theatre, free birthday cake and. Polar Bears International has created a new earth awareness day, Arctic Sea Ice Visit the Parks Canada outreach education team at the Assiniboine Park Zoo. Join us for GEOCACHING DAY at Assiniboine Park Zoo this Saturday, September Sat AM UTC · Assiniboine Park & Zoo · Winnipeg, MB, Canada. Canada Day Fireworks; Winnipeg Canada Day Weekend; Canada Day Celebrations . Crescent Drive Park, Crescent Dr, Winnipeg. Free. The Forks is boasting its biggest Canada Day celebration thanks to The first people in the zoo each day will get a free polar bear token. The Assiniboine Park Zoo is celebrating Canada's th birthday with Each day from July 1 to 3, the first visitors will receive a free polar. Canada Where to celebrate Canada Day in Winnipeg The Assiniboine Park Zoo is hosting events through the weekend including The St. Boniface Museum and Fort Gibraltar will have free admission and a number of. Canada Day? Read our Top Things to Do in Winnipeg on Canada Day article. Grant Park Shopping Centre, Saturday, July 1: Closed. In celebration of our great nation, Assiniboine Park Zoo will host Canada Day festivities on July long weekend. Visitors can enjoy a festive. Canada Day is being celebrated far and wide this year to mark the at the Assiniboine Park Zoo each day (July ) will receive a free. -

Waters Fur Trade 9/06.Indd

WATERS OF THE FUR TRADE Self-Directed Drive & Paddle One or Two Day Tour Welcome to a Routes on the Red self-directed tour of the Red River Valley. These itineraries guide you through the history and the geography of this beautiful and interesting landscape. Several different Routes on the Red, featuring driving, cycling, walking or canoeing/kayaking, lead you on an exploration of four historical and cultural themes: Fur Trading Routes on the Red; Settler Routes on the Red; Natural and First Nations Routes on the Red; and Art and Cultural Routes on the Red. The purpose of this route description is to provide information on a self-guided drive and canoe/kayak trip. While you enjoy yourself, please drive and canoe or kayak carefully as you are responsible to ensure your own safety and that these activities are within your skill and abilities. Every effort has been made to ensure that the information in this description is accurate and up to date. However, we are unable to accept responsibility for any inconvenience, loss or injury sustained as a result of anyone relying upon this information. Embark on a one or two day exploration of the Red River and plentiful waters of the Red. At the end of your second day, related waters. Fur trading is the main theme including a canoe you will have a lovely drive back to Winnipeg along the east or kayak paddle along the Red River to arrive at historic Lower side of the Red River. Fort Garry and its costumed recreation and interpretation of Accommodations in Selkirk are listed at the end of Day 1. -

Slippers of the Spirit

SLIPPERS OF THE SPIRIT The Genus Cypripedium in Manitoba ( Part 1 of 2 ) by Lorne Heshka he orchids of the genus Cypripedium, commonly known as Lady’s-slippers, are represented by some Tforty-five species in the north temperate regions of the world. Six of these occur in Manitoba. The name of our province is aboriginal in origin, borrowed Cypripedium from the Cree words Manitou (Great Spirit) and wapow acaule – Pink (narrows) or, in Ojibwe, Manitou-bau or baw. The narrows Lady’s-slipper, or referred to are the narrows of Lake Manitoba where strong Moccasin-flower, winds cause waves to crash onto the limestone shingles of in Nopiming Manitou Island. The First Nations people believed that this Provincial Park. sound was the voice or drumbeat of the Manitou. A look at the geological map of Manitoba reveals that the limestone bedrock exposures of Manitou Island have been laid down by ancient seas and underlies all of southwest Manitoba. As a result, the substrates throughout this region Lorne Heshka are primarily calcareous in nature. The Precambrian or Canadian Shield occupies the portion of Manitoba east of N HIS SSUE Lake Winnipeg and north of the two major lakes, to I T I ... Nunavut. Granitic or gneissic in nature, these ancient rocks create acidic substrates. In the north, the Canadian Shield Slippers of the Spirit .............................p. 1 & 10-11 adjacent to Hudson Bay forms a depression that is filled Loving Parks in Tough Economic Times ................p. 2 with dolomite and limestone strata of ancient marine Member Profile: June Thomson ..........................p. 3 origins. -

Municipal Officials Directory 2021

MANITOBA MUNICIPAL RELATIONS Municipal Officials Directory 21 Last updated: September 23, 2021 Email updates: [email protected] MINISTER OF MUNICIPAL RELATIONS Room 317 Legislative Building Winnipeg, Manitoba CANADA R3C 0V8 ,DPSOHDVHGWRSUHVHQWWKHXSGDWHGRQOLQHGRZQORDGDEOH0XQLFLSDO2IILFLDOV'LUHFWRU\7KLV IRUPDWSURYLGHVDOOXVHUVZLWKFRQWLQXDOO\XSGDWHGDFFXUDWHDQGUHOLDEOHLQIRUPDWLRQ$FRS\ FDQEHGRZQORDGHGIURPWKH3URYLQFH¶VZHEVLWHDWWKHIROORZLQJDGGUHVV KWWSZZZJRYPEFDLDFRQWDFWXVSXEVPRGSGI 7KH0XQLFLSDO2IILFLDOV'LUHFWRU\FRQWDLQVFRPSUHKHQVLYHFRQWDFWLQIRUPDWLRQIRUDOORI 0DQLWRED¶VPXQLFLSDOLWLHV,WSURYLGHVQDPHVRIDOOFRXQFLOPHPEHUVDQGFKLHI DGPLQLVWUDWLYHRIILFHUVWKHVFKHGXOHRIUHJXODUFRXQFLOPHHWLQJVDQGSRSXODWLRQV,WDOVR SURYLGHVWKHQDPHVDQGFRQWDFWLQIRUPDWLRQRIPXQLFLSDORUJDQL]DWLRQV0DQLWRED([HFXWLYH &RXQFLO0HPEHUVDQG0HPEHUVRIWKH/HJLVODWLYH$VVHPEO\RIILFLDOVRI0DQLWRED0XQLFLSDO 5HODWLRQVDQGRWKHUNH\SURYLQFLDOGHSDUWPHQWV ,HQFRXUDJH\RXWRFRQWDFWSURYLQFLDORIILFLDOVLI\RXKDYHDQ\TXHVWLRQVRUUHTXLUH LQIRUPDWLRQDERXWSURYLQFLDOSURJUDPVDQGVHUYLFHV ,ORRNIRUZDUGWRZRUNLQJLQSDUWQHUVKLSZLWKDOOPXQLFLSDOFRXQFLOVDQGPXQLFLSDO RUJDQL]DWLRQVDVZHZRUNWRJHWKHUWREXLOGVWURQJYLEUDQWDQGSURVSHURXVFRPPXQLWLHV DFURVV0DQLWRED +RQRXUDEOHDerek Johnson 0LQLVWHU TABLE OF CONTENTS MANITOBA EXECUTIVE COUNCIL IN ORDER OF PRECEDENCE ............................. 2 PROVINCE OF MANITOBA – DEPUTY MINISTERS ..................................................... 5 MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY ............................................................ 7 MUNICIPAL RELATIONS .............................................................................................. -

Divided Prairie City Summary

summary the divided prairie city Income Inequality Among Winnipeg’s Neighbourhoods, 1970–2010 Edited by Jino Distasio and Andrew Kaufman Tom Carter, Robert Galston, Sarah Leeson-Klym, Christopher Leo, Brian Lorch, Mike Maunder, Evelyn Peters, Brendan Reimer, Martin Sandhurst, and Gina Sylvestre. This handout summarizes findings from The Divided Prairie City released by the Institute of Urban Studies Incomes are growing less (IUS) at The University of Winnipeg. 4 equal in Winnipeg. The IUS is part of a Neighbourhood Change Research Partner- ship (NCRP) funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities From 1970 to 2010, income inequality in Winnipeg grew by 20%. Research Council of Canada (SSHRC). Led by the Cities Cen- • 40% of Winnipeg’s neighbourhoods experienced declining tre at the University of Toronto, this study examines income incomes from 1980 to 2010—only 16% of Winnipeg’s neigh- inequality in Halifax, Montreal, Toronto, Hamilton, Winnipeg, bourhoods experienced increasing incomes. Calgary, and Vancouver. • Income inequality has not grown in Winnipeg to the same extent that it has in Toronto, Calgary, or Vancouver. Instead, Winnipeg resembles cities like Edmonton and Halifax because Income inequality is of lower concentrations of ultra high-income individuals. growing in Canada. Middle-income neighbour- 1 hoods are disappearing. Canadians believe that we live in a middle-class country, yet research 5 points to a growing income gap bet ween rich and poor neighbour- • From 1980 to 2010, one quarter of Winnipeg’s middle and up- hoods while the middle-income group shrinks. per middle-income neighbourhoods saw incomes decline to below average amounts. Incomes grew in only 13% of mid- Fourteen per cent of all income in Canada is now received by dle-income areas to above-average levels. -

5G Cell “Towers” in Winnipeg Neighbourhoods No Radiation Without Consultation

5G Winnipeg Awareness 3rd 5G CALL TO ACTION, 6 June 2020 TO: Mayor Bowman and City Councillors Province of Manitoba Manitoba Hydro Government of Canada ------------- No 4G/ 5G Cell “towers” in Winnipeg Neighbourhoods No Radiation without Consultation June 6, 2020 To all Winnipeggers and friends of Winnipeggers concerned about wireless 5G rollout, especially the installations of all sizes of cellular network antennas close to our homes CITY OF WINNIPEG The process for the City of Winnipeg to begin permitting of small cell antennas is underway. At least 3,400 small 4G/5G antennas and perhaps more than 7,000, many in our neighbourhoods. On lamp posts, hydro poles, traffic lights, sides and atop buildings. At least one on every block. Emitting 4G LTE 24/7 and then adding 5G when the technology is ready. POSSIBLE ACTIONS: 1. For the next Innovation, Economic and Development (IED) Standing Committee meeting -perhaps Monday, June 15th: • Delegate (=present) via phone, Skype or Zoom and/or submit a written report. Contact the City Clerk at https://www.winnipeg.ca/shared/htmlsnippets/MailForm.asp?Recipient=CityClerks&Title=DMIS%20Contact%2 0Form&Subjects=Feedback Watch to see when the next IED meeting will be and whether “small cells” are on the agenda: http://clkapps.winnipeg.ca/dmis/DocSearch.asp?CommitteeType=ASD&DocumentType=A • Send emails to Mayor Bowman and each City of Winnipeg Councillor (not just yours) - the more, the better (contact information below) 1/4 A SUGGESTED MESSAGE: Mention that you are a stakeholder, too. Just as the telecommunications providers have a voice, so should we. -

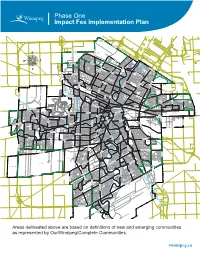

Impact Fee Implementation Plan

Phase One Impact Fee Implementation Plan ROSSER-OLD KILDONAN AMBER TRAILS RIVERBEND LEILA NORTH WEST KILDONAN INDUSTRIAL MANDALAY WEST RIVERGROVE A L L A TEMPLETON-SINCLAIR H L A NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL INKSTER GARDENS THE MAPLES V LEILA-McPHILLIPS TRIANGLE RIVER EAST MARGARET PARK KILDONAN PARK GARDEN CITY SPRINGFIELD NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL PARK TYNDALL PARK JEFFERSON ROSSMERE-A KILDONAN DRIVE KIL-CONA PARK MYNARSKI SEVEN OAKS ROBERTSON McLEOD INDUSTRIAL OAK POINT HIGHWAY BURROWS-KEEWATIN SPRINGFIELD SOUTH NORTH TRANSCONA YARDS SHAUGHNESSY PARK INKSTER-FARADAY ROSSMERE-B BURROWS CENTRAL ST. JOHN'S LUXTON OMAND'S CREEK INDUSTRIAL WESTON SHOPS MUNROE WEST VALLEY GARDENS GRASSIE BROOKLANDS ST. JOHN'S PARK EAGLEMERE WILLIAM WHYTE DUFFERIN WESTON GLENELM GRIFFIN TRANSCONA NORTH SASKATCHEWAN NORTH DUFFERIN INDUSTRIAL CHALMERS MUNROE EAST MEADOWS PACIFIC INDUSTRIAL LORD SELKIRK PARK G N LOGAN-C.P.R. I S S NORTH POINT DOUGLAS TALBOT-GREY O R C PEGUIS N A WEST ALEXANDER N RADISSON O KILDARE-REDONDA D EAST ELMWOOD L CENTENNIAL I ST. JAMES INDUSTRIAL SOUTH POINT DOUGLAS K AIRPORT CHINA TOWN C IVIC CANTERBURY PARK SARGENT PARK CE TYNE-TEES KERN PARK NT VICTORIA WEST RE DANIEL McINTYRE EXCHANGE DISTRICT NORTH ST. BONIFACE REGENT MELROSE CENTRAL PARK SPENCE PORTAGE & MAIN MURRAY INDUSTRIAL PARK E TISSOT LLIC E-E TAG MISSION GARDENS POR TRANSCONA YARDS HERITAGE PARK COLONY SOUTH PORTAGE MISSION INDUSTRIAL THE FORKS DUGALD CRESTVIEW ST. MATTHEWS MINTO CENTRAL ST. BONIFACE BUCHANAN JAMESWOOD POLO PARK BROADWAY-ASSINIBOINE KENSINGTON LEGISLATURE DUFRESNE HOLDEN WEST BROADWAY KING EDWARD STURGEON CREEK BOOTH ASSINIBOIA DOWNS DEER LODGE WOLSELEY RIVER-OSBORNE TRANSCONA SOUTH ROSLYN SILVER HEIGHTS WEST WOLSELEY A NORWOOD EAST STOCK YARDS ST. -

Summer Family Fun During COVID-19

Summer Family Fun During COVID-19: What’s Open Many more facilities are expected to open soon with additional COVID-19 Protocols, stay tuned for a Phase 3 updated list! Museums, Zoos & More Assiniboine Park Zoo Open Daily from 9:00 am – 5:00 pm *Children 2 & under free with general admission https://www.assiniboineparkzoo.ca/zoo/home/plan-your-visit/hours-rates Manitoba Museum Open Saturdays & Sundays in June from 11:00 am – 5:00 pm https://manitobamuseum.ca/main/visit/hours-admissions/ Canadian Museum for Human Rights *Opening Wednesday, June 17th Open Tuesday to Saturday from 10:00am – 5:00 pm https://humanrights.ca/COVID-19 Winnipeg Railway Museum Open Daily from 10:00 am – 4:00 pm http://www.wpgrailwaymuseum.com Winnipeg Art Gallery Open Tuesday to Sunday 11:00 am – 5:00 pm, with extended Friday hours until 9:00 pm https://wag.ca/visit/hours-admission/ Living Prairie Museum Open Sundays 10:00 am – 5:00 pm https://www.winnipeg.ca/publicworks/parksOpenSpace/livingprairie/ Fort Whyte Alive Open Weekdays 9:00 am – 5:00 pm & Weekends 10:00 am – 5:00 pm https://www.fortwhyte.org The Golf Dome Mini Golf Open 10:00 am – 8:00 pm http://www.thegolfdome.ca/hours.php https://www.parentingduringthepandemic.com Water Fun The following Winnipeg spray pads are open from 9:30am-8:30pm daily: *Note that no washroom facilities are available at any of the following https://www.winnipeg.ca/cms/recreation/facilities/pools/spraypads.stm • Central Park • Fort Rouge • Freight House • Gateway • Jill Officer Park • Lindenwoods • Lindsey Wilson Park • Machray Park • Provencher Park • Park City West • River Heights • St. -

2015 Report on Park Assets

Appendix A 2015 Report on Park Assets Asset Management Branch Parks and Open Space Division Public Works Department Table of Contents Summary of Parks, Assets and Asset Condition by Ward Charleswood-Tuxedo-Whyte Ridge Ward ................................................................................................... 1 Daniel McIntyre Ward .................................................................................................................................. 9 Elmwood – East Kildonan Ward ................................................................................................................. 16 Fort Rouge – East Fort Garry Ward ............................................................................................................ 24 Mynarski Ward ........................................................................................................................................... 32 North Kildonan Ward ................................................................................................................................. 40 Old Kildonan Ward ..................................................................................................................................... 48 Point Douglas Ward.................................................................................................................................... 56 River Heights – Fort Garry Ward ................................................................................................................ 64 South Winnipeg – St. Norbert -

Property Taxes and Built Form: Mapping the City of Winnipeg By: Felipe A

Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg$ X.xx - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - -

Tenders Tel: (204) 947-1379 Fax: (204) 943-2279 Email: [email protected] Manitoba Infrastructure Tenders

Manitoba Heavy Construction Association Unit 3-1680 Ellice Ave. Winnipeg, MB R3H 0Z2 Tenders Tel: (204) 947-1379 Fax: (204) 943-2279 www.mhca.mb.ca Email: [email protected] Manitoba Infrastructure Tenders Reference No. 0000063932 – STRUCTURE REHABILITATION (STRUCTURES) OVER THE SEINE RIVER DIVERSION Project No. 6805 Location: Manitoba Tender Availability: Currently Available Due: 1:00 PM, August 29, 2017 Owner: Manitoba Infrastructure Phone: 204-794-2243 Note: Rehabilitation and extension of an Eight (8)-Span Treated Timber Bridge over Seine River Diversion on Municipal Road 30E, located in the South East ¼ of Section 24-08-05E, Municipality of Tache, Bridge Site No. 3606-00. Your Voice Reference No. 0000063988 – BITUMINOUS PAVEMENT Project No. X03765 Location: Manitoba Tender Availability: Currently Available Due: 1:00 PM, August 29, 2017 Owner: Manitoba Infrastructure Phone: 204-726-6800 Heard Note: 6.1KM East of West Junction PTH 1A to PR 270 (Eastbound Lanes). Reference No. 0000063310 – REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL FOR PRELIMINARY DESIGN OF A NEW FISHWAY Project No. 2017-37-WMS-O Location:Manitoba Tender Availability: Currently Available Due: 1:00 PM, August 30, 2017 Owner: Manitoba Infrastructure Phone: 204-945-8535 he Manitoba Heavy Construction Note: Water Management Engineering and Construction Branch is inviting qualified Engineering Service Providers (ESP) to submit a Association (MHCA) is the voice proposal to undertake Professional Engineering Services to complete preliminary design of a new fishway for the Fairford Dam. Tof Manitoba’s