Synthetic Biology. Latest Developments, Biosafety

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biohazardous Waste Treatment

Biological Safety: Principles & Applications for Lab Personnel Presented by: Biological Safety Office http://biosafety.utk.edu Introduction OVERVIEW OF BIOSAFETY PROGRAM Introduction to Laboratory Safety When entering the laboratory environment you are likely to contact hazards that you would not encounter on a daily basis. These can include: • Physical hazards • Chemical hazards • Radiological hazards • Biological hazards Biohazards Any biological agent or condition that poses a threat to human, animal, or plant health, or to the environment. Examples include, but not limited to: • Agents causing disease in humans, animals or plants (bacteria, viruses, etc.) • Toxins of biological origin • Materials potentially containing infectious agents or biohazards .Blood, tissues, body fluids etc. .Waste, carcasses etc. • Recombinant DNA (depends) • Nanoparticles w/biological effector conjugates (depends) Types of Biohazards: What they are.... How they’ll look.... Regulations & Standards The Institutional Biosafety Committee Institutional Biosafety Committees (IBC) are required by the National Institutes of Health Office of Biological Activities (NIH; OBA) for institutions that receive NIH funding and conduct research using recombinant or synthetic nucleic acids. The UT IBC is composed of 14 UT-affiliated members and 2 non-affiliated members, who collectively offer a broad range of experience in research, safety and public health. Functions of the IBC Projects requiring IBC review • Performing both initial and annual • Those involving recombinant -

Venter Institute

Genomics:GTL Program Projects J. Craig Venter Institute 42 Estimation of the Minimal Mycoplasma Gene Set Using Global Transposon Mutagenesis and Comparative Genomics John I. Glass* ([email protected]), Nina Alperovich, Nacyra Assad-Garcia, Shibu Yooseph, Mahir Maruf, Carole Lartigue, Cynthia Pfannkoch, Clyde A. Hutchison III, Hamilton O. Smith, and J. Craig Venter J. Craig Venter Institute, Rockville, MD The Venter Institute aspires to make bacteria with specific metabolic capabilities encoded by artificial genomes. To achieve this we must develop technologies and strategies for creating bacterial cells from constituent parts of either biological or synthetic origin. Determining the minimal gene set needed for a functioning bacterial genome in a defined laboratory environment is a necessary step towards our goal. For our initial rationally designed cell we plan to synthesize a genome based on a mycoplasma blueprint (mycoplasma being the common name for the class Mollicutes). We chose this bacterial taxon because its members already have small, near minimal genomes that encode limited metabolic capacity and complexity. We took two approaches to determine what genes would need to be included in a truly minimal synthetic chromosome of a planned Mycoplasma laboratorium: determination of all the non-essential genes through random transposon mutagenesis of model mycoplasma species, Mycoplasma genitalium, and comparative genomics of a set of 15 mycoplasma genomes in order to identify genes common to all members of the taxon. Global transposon mutagenesis has been used to predict the essential gene set for a number of bac- teria. In Bacillus subtilis all but 271 of bacterium’s ~4100 genes could be knocked out. -

Microbial Identification Framework for Risk Assessment

Microbial Identification Framework for Risk Assessment May 2017 Cat. No.: En14-317/2018E-PDF ISBN 978-0-660-24940-7 Information contained in this publication or product may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, for personal or public non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, unless otherwise specified. You are asked to: • Exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; • Indicate both the complete title of the materials reproduced, as well as the author organization; and • Indicate that the reproduction is a copy of an official work that is published by the Government of Canada and that the reproduction has not been produced in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada. Commercial reproduction and distribution is prohibited except with written permission from the author. For more information, please contact Environment and Climate Change Canada’s Inquiry Centre at 1-800-668-6767 (in Canada only) or 819-997-2800 or email to [email protected]. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment and Climate Change, 2016. Aussi disponible en français Microbial Identification Framework for Risk Assessment Page 2 of 98 Summary The New Substances Notification Regulations (Organisms) (the regulations) of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA) are organized according to organism type (micro- organisms and organisms other than micro-organisms) and by activity. The Microbial Identification Framework for Risk Assessment (MIFRA) provides guidance on the required information for identifying micro-organisms. This document is intended for those who deal with the technical aspects of information elements or information requirements of the regulations that pertain to identification of a notified micro-organism. -

Field Trials for GM Food Get Green Light in India

NATURE|Vol 448|23 August 2007 NEWS IN BRIEF Field trials for GM food Asthmatics win payment in diesel-fumes lawsuit get green light in India Asthma patients in Tokyo last week welcomed a cash settlement India’s first genetically modified (GM) food from car manufacturers and crop is a step closer to reaching the dining the Japanese government. The table. The government has approved field one-time payment resolved a trials for a strain of brinjal (aubergine) decade-long legal battle in which carrying a Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis) gene. the asthmatics blamed diesel car Jalna-based Mahyco, the Indian venture fumes for their illness. KIM KYUNG-HOON/REUTERS of US seed giant Monsanto, claims its insect- The automakers, including resistant variety gives better yields with Toyota, Honda and Nissan, will less pesticide use. To avoid possible cross- provide ¥1.2 billion (US$10.5 contamination with farmers’ crops, the trials million) to the plaintiffs, and a will be carried out in government farms. further ¥3.3 billion to support But critics already campaigning against Bt a five-year health plan for the cotton — currently the only GM crop grown patients. The central government in India — say the brinjal trials are illegal. and Tokyo metropolitan Full biosafety data on the brinjal tests government will each contribute ¥6 billion to the medical programme. have not yet been generated, says Kavitha Kuruganti of the Centre for Sustainable scientists — to pay for relocation, housing starting dose “should be considered for Agriculture, based in Hyderabad: “The trials and research. “This is about the rescue of patients with certain genetic variations”. -

Role of Protein Phosphorylation in Mycoplasma Pneumoniae

Pathogenicity of a minimal organism: Role of protein phosphorylation in Mycoplasma pneumoniae Dissertation zur Erlangung des mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorgrades „Doctor rerum naturalium“ der Georg-August-Universität Göttingen vorgelegt von Sebastian Schmidl aus Bad Hersfeld Göttingen 2010 Mitglieder des Betreuungsausschusses: Referent: Prof. Dr. Jörg Stülke Koreferent: PD Dr. Michael Hoppert Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 02.11.2010 “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.” (Albert Einstein) Danksagung Zunächst möchte ich mich bei Prof. Dr. Jörg Stülke für die Ermöglichung dieser Doktorarbeit bedanken. Nicht zuletzt durch seine freundliche und engagierte Betreuung hat mir die Zeit viel Freude bereitet. Des Weiteren hat er mir alle Freiheiten zur Verwirklichung meiner eigenen Ideen gelassen, was ich sehr zu schätzen weiß. Für die Übernahme des Korreferates danke ich PD Dr. Michael Hoppert sowie Prof. Dr. Heinz Neumann, PD Dr. Boris Görke, PD Dr. Rolf Daniel und Prof. Dr. Botho Bowien für das Mitwirken im Thesis-Komitee. Der Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes gilt ein besonderer Dank für die finanzielle Unterstützung dieser Arbeit, durch die es mir unter anderem auch möglich war, an Tagungen in fernen Ländern teilzunehmen. Prof. Dr. Michael Hecker und der Gruppe von Dr. Dörte Becher (Universität Greifswald) danke ich für die freundliche Zusammenarbeit bei der Durchführung von zahlreichen Proteomics-Experimenten. Ein ganz besonderer Dank geht dabei an Katrin Gronau, die mich in die Feinheiten der 2D-Gelelektrophorese eingeführt hat. Außerdem möchte ich mich bei Andreas Otto für die zahlreichen Proteinidentifikationen in den letzten Monaten bedanken. Nicht zu vergessen ist auch meine zweite Außenstelle an der Universität in Barcelona. Dr. Maria Lluch-Senar und Dr. -

A New Level 3 Biosafety and Astrobiology Laboratory in Pieve A

PAN.R.C.- A New Level 3 Biosafety and Astrobiology Laboratory in Pieve a Nievole (PT) Tasselli, D. TS Corporation Srl - Astronomy and Astrophysics Department Via Rugantino, 71, 00169 Roma RM - Italy E-mail:[email protected] Ferrara, G. TS Corporation Srl - Biology Department Via Cavalcanti, 10, 51010 Massa e Cozzile PT - Italy E-mail:[email protected] Ricci, S. TS Corporation Srl - Meteorogical and Climatic Change Department Via Rugantino, 71, 00169 Roma RM - Italy E-mail:[email protected] Bianchi, P. TS Corporation Srl - Geology and Geophysics Department Via Rugantino, 71, 00169 Roma RM - Italy E-mail:[email protected] Abstract We report our proposal for the establishment of a biocontainment and astrobiology laboratory in a strategic area of Pieve a Nievole (PT) at 28 mt above sea level - to face the lack of biological and astrobiological research centers and all the social, economic and cultural consequences that this project implicate. The structure will be built under the Horizon 2020 work program 2018-2020 - European Research Infrastructures (in- cluding e-Infrastructures), and will enable the development of major re- arXiv:1811.05201v1 [astro-ph.IM] 13 Nov 2018 search project. Keyword: astrobiology - biosafety - biosecurity - BSL3 - containment - research center - biological risk - biological agents - new research facility - location: Pieve a Nievole (PT) This paper was prepared with the LATEX 1 1 Introduction project that involves the use of biological agents from second or third group, must The environment that surrounds us is pop- ask permission and wait for the technical ulated by biological agents such as bacte- time to use the currently available facili- ria, viruses or fungi. -

Genetically Modified Tree Policy Technology and Innovation, Sustainability Issued By: Date: 18/06/2021 and Institutional Affairs Code: POL.00.0044 Revision

Title: Genetically Modified Tree Policy Technology and Innovation, Sustainability Issued by: Date: 18/06/2021 and Institutional Affairs Code: POL.00.0044 Revision: Contents 1 PURPOSE ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 2 REFERENCE DOCUMENTS ................................................................................................................................. 4 3 TERMS, DEFINITIONS AND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................. 4 4 GUIDELINES ........................................................................................................................................................ 8 4.1 Principles ......................................................................................................................................................... 8 4.2 Governance and Ethics .................................................................................................................................. 9 4.2.1 Advisory Committee .................................................................................................................................. 9 4.2.1.1 Purpose ..................................................................................................................................................... 9 4.2.1.2 Responsibilities ....................................................................................................................................... -

Biosafety Manual

Office of Environment, Health & Safety Biosafety Manual Table of Contents Introduction 2 Institutional Review of Biological Research 3 Introduction to CLEB 3 Prerequisites to Initiation of Work 3 Completion and Submission of the BUA Application 4 Committee Review and Approval of Applications 7 Amending the BUA 9 Risk Assessment 10 Classification of Agents by Risk Group 10 Recombinant DNA 11 Risk Factors of the Agents 13 Exposure Sources 13 Containment of Biological Agents 15 Biosafety Levels 15 Practices and Procedures 16 Engineering Controls 19 Waste Disposal 23 Emergency Plans and Reporting 25 Spill Cleanup Procedures 25 Exposure Response Protocols 28 Reporting 28 Appendix 1: Working with Viral Vectors 29 Adenovirus 32 Adeno-associated Virus 34 Lentivirus 35 Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (MoMuLV or MMLV) 37 Rabies virus 38 Sendai virus 41 References 42 Appendix 2: Important Contact Information 43 Appendix 3: Bloodborne Pathogen Considerations 44 Appendix 4: Useful Resources 45 1 Section I. Introduction UC Berkeley is committed to maintaining a healthy and safe workplace for all laboratory workers, students and visitors. This manual is an overview of the administrative steps necessary to obtain and maintain approval for the use of biological materials in laboratories, as well as a reference for good work prac- tices and safe handling of other potentially infectious materials (OPIM). A variety of procedures are conducted on campus which use many different agents. This manual addresses the biological hazards frequently encountered in labora- tories. Biological hazards include infectious or toxic microorganisms (including viral vectors), potentially infectious human substances, and research animals and their tissues, in cases from which transmission of infectious agents or tox- ins is reasonably anticipated. -

FORESTS and GENETICALLY MODIFIED TREES FORESTS and GENETICALLY MODIFIED TREES

FORESTS and GENETICALLY MODIFIED TREES FORESTS and GENETICALLY MODIFIED TREES FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2010 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. All rights reserved. FAO encourages the reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Non-commercial uses will be authorized free of charge, upon request. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes, including educational purposes, may incur fees. Applications for permission to reproduce or disseminate FAO copyright materials, and all queries concerning rights and licences, should be addressed by e-mail to [email protected] or to the Chief, Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Office of Knowledge Exchange, Research and Extension, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy. © FAO 2010 iii Contents Foreword iv Contributors vi Acronyms ix Part 1. THE SCIENCE OF GENETIC MODIFICATION IN FOREST TREES 1. Genetic modification as a component of forest biotechnology 3 C. -

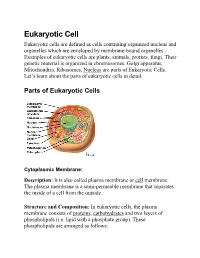

Eukaryotic Cell Eukaryotic Cells Are Defined As Cells Containing Organized Nucleus and Organelles Which Are Enveloped by Membrane-Bound Organelles

Eukaryotic Cell Eukaryotic cells are defined as cells containing organized nucleus and organelles which are enveloped by membrane-bound organelles. Examples of eukaryotic cells are plants, animals, protists, fungi. Their genetic material is organized in chromosomes. Golgi apparatus, Mitochondria, Ribosomes, Nucleus are parts of Eukaryotic Cells. Let’s learn about the parts of eukaryotic cells in detail. Parts ot Eukaryotic Cells Cytoplasmic Membrane: Description: It is also called plasma membrane or cell membrane. The plasma membrane is a semi-permeable membrane that separates the inside of a cell from the outside. Structure and Composition: In eukaryotic cells, the plasma membrane consists of proteins , carbohydrates and two layers of phospholipids (i.e. lipid with a phosphate group). These phospholipids are arranged as follows: • The polar, hydrophilic (water-loving) heads face the outside and inside of the cell. These heads interact with the aqueous environment outside and within a cell. • The non-polar, hydrophobic (water-repelling) tails are sandwiched between the heads and are protected from the aqueous environments. Scientists Singer and Nicolson(1972) described the structure of the phospholipid bilayer as the ‘Fluid Mosaic Model’. The reason is that the bi-layer looks like a mosaic and has a semi-fluid nature that allows lateral movement of proteins within the bilayer. Image: Fluid mosaic model. Orange circles – Hydrophilic heads; Lines below – Hydrophobic tails. Functions • The plasma membrane is selectively permeable i.e. it allows only selected substances to pass through. • It protects the cells from shock and injuries. • The fluid nature of the membrane allows the interaction of molecules within the membrane. -

PA00XCSB.Pdf

Leidos Proprietary 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A summary of efforts for the planned, ongoing, and completed projects for the Malaria Vaccine Development Program (MVDP) contract for this reporting period are herein detailed. A compiled Gantt chart including activities associated with each of the projects has been created and included as an attachment to this report. Ongoing projects that will continue through FY2019 include two vaccine development projects, the CSP vaccine development project (CSP Vaccine) and liver stage vaccine development project (Liver Stage Vaccine), as well as the clinical study with RH5 (RH5.1 Clinical Study), the latter to assess long-term immunogenicity in RH5.1/AS01 vaccinees. Of note is that while both the CSP and the liver stage vaccine development projects were initiated as epitope-based projects, these have since been realigned to target whole proteins; therefore, the project names have also been realigned to remove “epitope-based.” Expansion of work on the RCR complex into a vaccine development project (RCR Complex) occurred in early FY2019 and this project will continue until the end date of the contract. Lastly, a new project, the RH5.1 human monoclonal antibody identification and development project (RH5.1 Human mAb), was initiated in early FY2019 and will continue until the end date of the contract. Two projects were completed in FY2019, the blood stage epitope-based vaccine development project and the PD1 blockade inhibitor project (PD1 Block Inh). Leidos continues to seek collaborators for information exchange under NDA, reagent exchange under MTA, and collaboration under CRADA, to expand our body of knowledge and access to reagents with minimal cost to the program. -

Appendix 1*) for Essential Information Very Well Illustrated in Google and Wikipedia

Appendix 1*) For Essential Information Very Well Illustrated in Google and Wikipedia *) in Support of the Text with Literature Citations. Referrals to illustrations in Appendix 2. Cancer in the Plant. The insertion of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens circular plasmid T (transferred) DNA into the genome of its new host, the plant (Gelvin BS. Microbiol Molecular Biol Rev 2003;67:16–37). The plant cancer “crown gall” (agrocallus; Agrobacterial crown gall) consists of malignantly transformed cells replicating the agrobacterial T DNA plasmid (reviewed in postscript Table XXXV). For reference: Koncz C Mayerhofer R Koncz-Kálmán Zs et al EMBO J 1990;9:1337–1346. Transfer of potentially oncogenic bacterial genes and proteins to patients: Septicemic Bacteroides enterotoxigenic (Sinkovics J G & Smith JP Cancer 1970;25:663–671; Viljoen KS et al PLoS One 2015;10(3):e0119462); Bartonella bacilliformis etc (Guy L et al PLoS Genet 2013;9(3):e1003393; Harms A & Dehio C Clin Microbiol Rev 2012;25:42–78; Llosa M et al Trends Microbiol 2012;20:355–9; Minnick MF et al PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014;6(7):e2919); Helicobacter pylori (Bonsor DA et al J Biol Chem 2015;pii:jbc.M115.641829; Su YL et al J Immunol 2015;194:3997–4007; Vaziri F et al Pathog Dis 2015;73(3). pii.ftu021); Porphyromonas gingivalis (Katz J et al Int J Oral Sci 2011;3:209–215); Tuberculous infections with A. tumefaciens in patients (Ramirez FC et al Clin Infect Dis 1992;15:938–940). DNA-binding Antibodies. DNA- (or RNA-) binding proteins use zink finger motifs, leucine zippers and winged (beta-sheet loops) helix-turn helix motifs (HTH, two helices separated by the loop, RNA/DNA-binding domains) in recognition of RNA/DNA receptors for attachment.