Click Here to Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Holcad, November 7, 2007 (Page 1)

a-1 front - holcad (24”) 20060816cad YELLOW MAGENTA CYAN BLACK 0% 5%5% 10% 10% 20% 20% 30% 30% 40% 40% 50% 50% 60% 60%70% 80%70% 90% 80% 95% 90% 100% 95% 100% Friday, The May 2, 2008 New Wilmington, Pa. 12 pages Volume CXXIX Number 22 HHWestminsterolcadolcad College’s student newspaper since 1884 In this ‘She danced edition... “A Senior Celebration” Combined band concert honors seniors with her heart’ By Jenna C. Retort “All of the pieces that we are The evening will conclude with Campus gathers to celebrate Interim Editor-in-Chief playing are significant works,” both ensembles playing the Alma Greig said. “These works are es- Mater, arranged by Cormac Can- the life of Loren Mistovich The department of music will tablished as the pinnacle of band non and featuring junior music ed- conclude the semester with a literature and works that the stu- ucation major, Stephanie Witzor- By Christine Line dancing and music. One speaker weekend of music, starting with dents should have the opportunity reck as the vocalist. Managing Editor mentioned her particular love for the combined Symphonic Band to play.” “Many think that this is just an- ballet, and friends and family as- and Wind Ensemble concert The symphonic band, com- other band concert, but if people Students and members of the serted that she would come alive Under the direction of Dr. R. prised of students of all majors, stay in their rooms, they will miss campus community gathered in through dancing. According to a Senior Send Off Tad Greig, the Wind Ensemble and will feature pieces from composers an opportunity to hear great mu- the Chapel on Wednesday, April press release, Mistovich still found Syphonic Band will perform their such as, John Stanhope, Ceasar sic,” junior Kevin Shields said. -

April Archive

A Tony-winning director finds a rewarding new way to build a musical in the age of covid-19 Washington Post, 4/30/2020: “In April, 24 actors, several designers and one Tony Award- winning director, Diane Paulus, embarked on a groundbreaking digital “workshop” for a Broadway-bound revival of the musical ‘1776.’ The story of a revolution with a revolutionary non-binary, gender-inclusive cast. And they did it under the most harrowing of circumstances: a pandemic.” New York’s Public Theater Debuts the First Great Play of the Zoom Era Vogue, 4/30/2020: “Wednesday night represented something of a milestone: the world premiere of a play written specifically about this strange time we are now living in and staged to take advantage of the fact that almost none of the actors could be in the same room together. The play was What Do We Need to Talk About? by Richard Nelson, the latest installment of his narrative series The Apple Family Plays. It was staged and livestreamed by New York’s Public Theater, the home of the first four plays in this series.” How the CDC Museum in Atlanta Is Documenting COVID- 19 for Future Generations Conde Nast Traveler, 4/29/2020: “The curatorial team at the country’s flagship public- health agency is collecting artifacts, documents, testimonials, imagery, and more. “ Tango in the age of coronavirus: How a Zoom party connects dancers across the globe Los Angeles Times, 4/29/2020: “Like many other gatherings in the age of social distancing, . tango lovers [are] united via the video conferencing platform Zoom for the biweekly -

Download Lean on Song Video

Download lean on song video LINK TO DOWNLOAD Lean On song by Celina Sharma, Emiway Bantai now on JioSaavn. English music album Lean On. Download song or listen online free, only on renuzap.podarokideal.ru Duration: 2 min. Lean On Song Download- Listen Lean On MP3 song online free. Play Lean On album song MP3 by Celina Sharma and download Lean On song on renuzap.podarokideal.ru Major Lazer x DJ Snake feat_ MØ - Lean On - Gisher Music (Gisher Hits Vol 1). Free mp3 download. Oct 20, · Download/Stream - renuzap.podarokideal.ru Follow Our Official Spotify Playlist: renuzap.podarokideal.ru Listen to More Tomm. Mar 23, · OFFICIAL MUSIC VIDEO // MAJOR LAZER & DJ SNAKE - LEAN ON (FEAT. MØ) "India is special and its beauty absolutely humbled me. When we toured there as Major Lazer, it was mind blowing to see our fan- base and we wanted to incorporate the attitude and positive vibes into our video and just do something that embodies the essence of Major Lazer. Listen and download Lean On (Ft MO) (Remix by Mehrbod) by Major Lazer and Dj Snake in MP3 format on Bia2. Apr 26, · ArtistsCAN – Lean On Me Watch, Stream, Listen and Share. All proceeds of the ArtistsCAN single are donated to the Canadian Red Cross to help fight COVID i. Lean On MP3 Song by The Harmony Group from the album Lean On - Single. Download Lean On song on renuzap.podarokideal.ru and listen Lean On - Single Lean On song offline. May 04, · [ Lyrics ] Lean On In - Jonny Houlihan | Top Music #LeanOnIn #JonnyHoulihan #TopMusic #Lyrics Click Like & Subscribe to update new Videos from Top Music ch. -

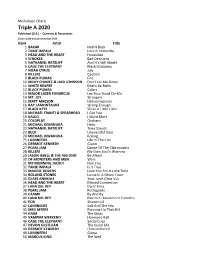

Triple a 2020

Mediabase Charts Triple A 2020 Published (U.S.) -- Currents & Recurrents January 2020 through December, 2020 Rank Artist Title 1 BAKAR Hell N Back 2 TAME IMPALA Lost In Yesterday 3 HEAD AND THE HEART Honeybee 4 STROKES Bad Decisions 5 NATHANIEL RATELIFF And It's Still Alright 6 CAGE THE ELEPHANT Black Madonna 7 NOAH CYRUS July 8 KILLERS Caution 9 BLACK PUMAS Fire 10 MILKY CHANCE & JACK JOHNSON Don't Let Me Down 11 WHITE REAPER Might Be Right 12 BLACK PUMAS Colors 13 MAJOR LAZER F/MARCUS Lay Your Head On Me 14 MT. JOY Strangers 15 MATT MAESON Hallucinogenics 16 RAY LAMONTAGNE Strong Enough 17 BLACK KEYS Shine A Little Light 18 MICHAEL FRANTI & SPEARHEAD I Got You 19 KALEO I Want More 20 COLDPLAY Orphans 21 MICHAEL KIWANUKA Hero 22 NATHANIEL RATELIFF Time Stands 23 BECK Uneventful Days 24 MICHAEL KIWANUKA Rolling 25 LUMINEERS Life In The City 26 DERMOT KENNEDY Giants 27 PEARL JAM Dance Of The Clairvoyants 28 KILLERS My Own Soul's Warning 29 JASON ISBELL & THE 400 UNIT Be Afraid 30 OF MONSTERS AND MEN Wars 31 MY MORNING JACKET Feel You 32 TAME IMPALA Is It True 33 MAGGIE ROGERS Love You For A Long Time 34 ROLLING STONES Living In A Ghost Town 35 GLASS ANIMALS Your Love (Deja Vu) 36 HEAD AND THE HEART Missed Connection 37 LANA DEL REY Doin' Time 38 PEARL JAM Retrograde 39 CAAMP By And By 40 LANA DEL REY Mariners Apartment Complex 41 EOB Shangri-LA 42 LUMINEERS Salt And The Sea 43 MEG MYERS Running Up That Hill 44 HAIM The Steps 45 VAMPIRE WEEKEND Harmony Hall 46 CAGE THE ELEPHANT Social Cues 47 DEVON GILFILLIAN The Good Life 48 DERMOT KENNEDY -

Issue Date: April 20Th 2020

Issue Date: April 20th 2020 # lw bp woc tfo artist single 1 1 1 19 17 THE WEEKND BLINDING LIGHTS theweeknd.com ***6 weeks at #1*** album: After Hours (Republic - Universal Music) 2 2 1 10 10 DUA LIPA PHYSICAL www.dualipa.com album: Future Nostalgia (Warner - Dancing Bear) 3 3 2 6 6 LADY GAGA STUPID LOVE twitter.com/ladygaga single (Interscope - Universal Music) 4 5 1 32 30 TONES AND I DANCE MONKEY www.tonesandi.com EP: The Kids Are Coming (Elektra -Dancing Bear) 5 15 5 2 2 DUA LIPA BREAK MY HEART www.dualipa.com album: Future Nostalgia (Warner - Dancing Bear) 6 7 6 32 29 POST MALONE CIRCLES postmalone.com album: Hollywood's Bleeding (Republic - Universal Music) 7 4 4 12 12 JONAS BROTHERS WHAT A MAN GOTTA DO jonasbrothers.com single (Republic - Universal Music) 8 14 2 29 29 MAROON 5 MEMORIES www.maroon5.com single (Interscope - Universal Music) 9 5 1 24 23 DUA LIPA DON'T START NOW www.dualipa.com album: Future Nostalgia (Warner - Dancing Bear) 10 12 8 17 16 HARRY STYLES ADORE YOU hstyles.co.uk album: Fine Line (Columbia - Menart) 11 19 2 31 28 REGARD RIDE IT djregardofficial.com single (Sony - Menart) 12 8 8 6 6 SZA X JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE THE OTHER SIDE szactrl.com single (RCA - Menart) 13 9 6 19 15 LEWIS CAPALDI BEFORE YOU GO www.lewiscapaldi.com album: Divinely Uninspired to a Hellish Extent - Extended Edition (Virgin - Universal Music) 14 13 4 26 26 MEDUZA FEAT. BECKY HILL & GOODBOYS LOSE CONTROL www.soundofmeduza.com single (Virgin - Universal Music) 15 10 1 42 42 SHAWN MENDES FEAT. -

Encore Dance Ad 202101-1.Indd

MEET OUR ENCORE DREAM TEAM ... Marcel Wilson has studied a wide range of dance and movement including hip-hop, contemporary, tap, jazz, and ballet with some of the most influential teachers and choreographers from around the world. This led him to further his education at Oklahoma City University where he graduated with a Bachelor Degree in Dance Performance. Since his graduation, OCU presented him with a Distinguished Alumni award for his extraordinary contributions in the entertainment industry. Marcel has performed with artists such as Janet Jackson, Christina Aguilera, Cher and Beyonce. Now living in Las Vegas, his unique choreographic style can be seen in Christina Aguilera’s Xperience Residency show at Planet Hollywood Resort & Casino. Recently he choreographed “Glow” a Christmas show, seen by thousands, at Fashion Show Mall on the Vegas strip. Marcel has choreographed for artists such as Wayne Brady, Gloria Trevi, Toni Braxton, Donny Osmond, Paulina Rubio, and Cher and is no stranger to television, contributing choreography for shows such as “The Voice,” “America’s Got Talent,” and “Dancing with The Stars.” His choreography has traveled the seas with “Sequin & Feathers,” “Live, Love, Legs,” and “Three” for the Royal Caribbean Cruise Lines. Marcel received a World Choreography Award for Outstanding Choreography in a concert for the top-grossing world tour, Cher: Marcel Marcel “Dressed to Kill,” and has recently worked with UK’s X-Factor as an Associate Creative Director expanding his horizons in the industry. Marcel and his brother, Wilson Wilson Kevin, make up the dynamic creative team internationally known as “Mr. Wilson Entertainment.” Gelsey Weiss-Mahanes has enjoyed a professional performing career in LA and NYC. -

KMGC Productions KMGC Song List

KMGC Productions KMGC Song List Title Title Title (We Are) Nexus 2 Faced Funks 2Drunk2Funk One More Shot (2015) (Cutmore Club Powerbass (2 Faced Funks Club Mix) I Can't Wait To Party (2020) (Original Mix) Powerbass (Original Club Mix) Club Mix) One More Shot (2015) (Cutmore Radio 2 In A Room Something About Your Love (2019) Mix) El Trago (The Drink) 2015 (Davide (Original Club Mix) One More Shot (2015) (Jose Nunez Svezza Club Mix) 2elements Club Mix) Menealo (2019) (AIM Wiggle Mix) You Don't Stop (Original Club Mix) They'll Never Stop Me (2015) (Bimbo 2 Sides Of Soul 2nd Room Jones Club Mix) Strong (2020) (Original Club Mix) Set Me Free (Original Club Mix) They'll Never Stop Me (2015) (Bimbo 2Sher Jones Radio Mix) 2 Tyme F. K13 Make It Happ3n (Original Club Mix) They'll Never Stop Me (2015) (Jose Dance Flow (Jamie Wright Club Mix) Nunez Radio Mix) Dance Flow (Original Club Mix) 3 Are Legend, Justin Prime & Sandro Silva They'll Never Stop Me (2015) (Sean 2 Unlimited Finn Club Mix) Get Ready For This 2020 (2020) (Colin Raver Dome (2020) (Original Club Mix) They'll Never Stop Me (2015) (Sean Jay Club Mix) 3LAU & Nom De Strip F. Estelle Finn Radio Mix) Get Ready For This 2020 (2020) (Stay The Night (AK9 Club Mix) 10Digits F. Simone Denny True Club Mix) The Night (Hunter Siegel Club Mix) Calling Your Name (2016) (Olav No Limit 2015 (Cassey Doreen Club The Night (Original Club Mix) Basoski Club Mix) Mix) The Night (Original Radio Mix) Calling Your Name (Olav Basoski Club 20 Fingers F. -

Orlando 8:55 Pm - Awards

SCHEDULE OF EVENTS Thursday, May 13 5:00 PM - Junior, Teen, Senior Solos ORLANDO 8:55 PM - AWARDS Friday, May 14 7:30 AM - Solos Continued 12:35 PM - AWARDS 1:15 PM - Solos Continued 4:30 PM - AWARDS 5:10 PM - Solos Continued 9:10 PM - AWARDS Saturday, May 15 7:00 AM - Clermont Academy of Dance 7:00 AM - Drawdys Dance School 7:00 AM - Dance Dynasty 7:00 AM - In His Steps Dance Company 9:35 AM - AWARDS 2021 10:15 AM - Shell We Dance Academy 10:15 AM - Kidzdance 10:15 AM - Ruby Dance Center Part 1 regionals 11:45 AM - AWARDS 12:25 PM - Revolutions Dance Comp Part 1 12:25 PM - Star Acad. of Dance & Aerial Arts 12:25 PM - Tammys Dance Co 2:30 PM - AWARDS 3:10 PM - New Level Dance Company Part 1 5:40 PM - AWARDS 6:15 PM - New Level Dance Company Part 2 9:35 PM - AWARDS Sunday, May 16 7:00 AM - Edge Dance Studios Tank you 7:00 AM - Performers Edge Dance Center 11:00 AM - AWARDS 11:40 AM - Revolutions Dance Comp Part 2 11:40 AM - Center Stage Dance Studio for joining us! 11:40 AM - Dance by Holly Rock 11:40 AM - Full Force Dance Academy 11:40 AM - Ruby Dance Center Part 2 1:45 PM - AWARDS 2:25 PM - Duvall Dance Academy 2:25 PM - POP Dance 2:25 PM - 3D Motion Dance Center 4:50 PM - AWARDS 5:30 PM - Dance!nk by Davis 5:30 PM - Starz Choice Dance Academy 5:30 PM - The Dance Collective LLC 9:00 PM - AWARDS 9:20 PM - HIGH SCORE AWARDS SCORING SYSTEM AGE DIVISIONS COMPETITIVE LEVELS Up in the VIP (Hollywood Level Only) 295 - 300 Little Bigwigs: 7 & under (in Mini, Jr, Teen, Sr only) Diamond 283 - 294 Mini: 8-9 Off-Broadway - Recreational Level Platinum 275 - 282 Junior: 10 - 12 Broadway - Intermediate Level Gold 261 - 274 Teen: 13 - 15 Hollywood - Advanced Level Silver 246 - 260 Senior: 16 - 24 Meet the Judges.. -

Taylor Swift's Re-Recorded 'Fearless' Album Debuts at No. 1 on Billboard

Bulletin YOUR DAILY ENTERTAINMENT NEWS UPDATE APRIL 19, 2021 Page 1 of 27 INSIDE Taylor Swift’s Re-Recorded ‘Fearless’ • Polo G Scores Album Debuts at No. 1 on Billboard First Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 With Debut 200 Chart With Year’s Biggest Week of ‘Rapstar’ BY KEITH CAULFIELD • Billboard Parent P-MRC Strikes Deal to Invest In SXSW More than 12 years after Taylor Swift notched her released until now. first No. 1 album on the Billboard 200 chart in 2008 Fearless (Taylor’s Version) is the only No. 1 album of • Bad Bunny’s 2022 Tour Sells Out In with her second studio set Fearless, she’s back atop its kind: a re-recording of an artist’s (own or anoth- Record Time the list with a re-recorded version of the album, er’s) previously released album. titled Fearless (Taylor’s Version). The new set is her The Billboard 200 chart ranks the most popular • Gene Smith, Upbeat Billboard ninth No. 1 and scores the biggest week of 2021 for albums of the week in the U.S. based on multi-metric Ad Executive and any album. It launches with 291,000 equivalent album consumption as measured in equivalent album units. Champion of Latin units earned in the U.S. in the week ending April 15, Units comprise album sales, track equivalent albums Music, Dies at 88 according to MRC Data. (TEA) and streaming equivalent albums (SEA). Each • Shuttered Venue The original Fearless album debuted at No. 1 on the unit equals one album sale, or 10 individual tracks Operator Grant Billboard 200 chart dated Nov. -

Hot100-Aug 7, 2020

HOT100 LWP TWP Artist - Song Title (Label) TWS + - LWS PWS Adds 1 1 Lady Gaga & Ariana Grande - Rain On Me (Interscope) 1931 -4.5% 2018 1900 2 2 Weeknd - Blinding Lights (Republic/UMG) 1704 0.6% 1693 1679 1 3 3 Harry Styles - Adore You (Erskine/Columbia) 1683 0.4% 1676 1710 5 4 Dua Lipa - Break My Heart (Warner Music) 1409 -4.0% 1465 1320 4 5 Doja Cat - Say So (Kemosabe/RCA) 1369 -7.3% 1469 1455 6 6 Harry Styles - Watermelon Sugar (Columbia) 1362 3.8% 1312 1183 2 7 7 JP Saxe w/Julia Michaels - If The World Was Ending (Arista/Sony) 1275 0.1% 1274 1102 9 8 Justin Bieber w/Quavo - Intentions (RBMG/Def Jam/UMG) 1073 -4.8% 1124 1587 2 11 9 Lewis Capaldi - Before You Go (Vertigo/Capitol) 1039 -0.1% 1040 930 8 10 Megan Thee Stallion w/Beyonce - Savage (300 Entertainment/Columbia) 1038 -10.8% 1150 1233 14 11 Katy Perry - Daisies (Capitol) 959 3.9% 923 926 1 12 12 Gabby Barrett w/Charlie Puth - I Hope (Warner Music Nashville) 952 2.3% 931 845 13 13 Black Pontiac - Kate Rambo (Appreciated Music) 939 1.6% 924 816 1 15 14 Rami 411 - Dream (Indie) 918 1.7% 903 813 16 15 Susan Toney - Starlight (Strange Child) 856 5.8% 809 752 1 18 16 Saint Jhn - Roses (Godd Complexx/Hitco) 854 10.5% 773 902 2 19 17 Emmanuelle Sasson - Away From Me (Indie) 833 10.8% 752 705 27 18 Kenneth Roy - Empty Heart (Physico) 766 24.4% 616 478 20 19 Rick Fusion - A Little Bit Of Love (SirRic) 744 0.0% 744 650 21 20 Marshmello & Halsey - Be Kind (Astralwerks/UMG) 738 0.8% 732 883 25 21 Benee w/Gus Dapperton - Supalonely (Republic) 714 10.2% 648 650 26 22 Powfu w/Beabadoobee - Death Bed (Columbia) 695 8.1% 643 645 17 23 Trevor Daniel - Falling (Alamo/Interscope) 695 -14.2% 794 846 22 24 Michael Damian - Rock My Heart (Weir Brothers) 680 -0.6% 684 682 24 25 Black Eyed Peas X Ozuna X J. -

The Following 99 Folktales Were Collected from Storytellers in Tamil

The following 99 folktales were collected from storytellers in Tamil Nadu in the mid- 1990s by Stuart Blackburn, and were among those published in his book, Moral Fictions: Tamil Folktales from the Oral Tradition, Folklore Fellows Communications No. 278, Helsinki, Finland: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, 2005. The stories were told in Tamil, and were translated into English. Stuart Blackburn’s commentaries on the stories appear in the book, but are not included here. Story Page 1. Fraternal Unity 4 2. Straightening a Dog's Tail 6 3. Tenali Raman 8 4. The Guru and His Disciple 10 5. The Abducted Princess 14 6. A Brahmin Makes Good 19 7. A Cruel Daughter-in-Law 21 8. A Mosquito's Story 23 9. Loose Bowels 25 10. The Bouquet 28 11. Killing the Monkey-Husband 32 12. A Dog's Story 33 13. Poison Him, Marry Him 35 14. The Disfigured Eye 37 15. Family of the Deaf 39 16. A Thousand Flies in a Single Blow 40 17. A Parrot's Story 42 18. Four Thieves 43 19. The Blinded Heroine 45 20. A Daughter-in-Law's Revenge 48 21. The Three Diamonds 50 22. The Kind and the Unkind Girls 52 23. The Singing Bone 54 24. The Fish-Brother 56 25. The Story of a Little Finger 57 26. Cinderella 60 27. Animal Helpers 62 28. The Clever Sister 64 29. A Flea's Revenge 65 30. The Story of Krsna 66 31. The Seventh Son Succeeds 69 32. The Prince Who Understood 72 Animal Languages 33. A Dog, a Cat, and a Mouse 75 34. -

Relatório De Ecad

Relatório de Programação Musical Razão Social: Sistema 98 de Comunicação Ltda. CNPJ: 12.573.752/0001-20 Nome Fantasia: 98 FM - PRESIDENTE PRUDENTE SP Dial: Cidade: PRESIDENTE PRUDENTE UF: SP Data Hora Nome da música Nome do intérprete Nome do compositor Gravadora Vivo Mec. 01/09/2020 00:00:49 YOU ARE BEAUTIFUL JAMES BLUNT X 01/09/2020 00:04:21 THAT THING YOU DO! WONDERS X 01/09/2020 00:07:04 SUIT & TIE JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE FEAT. JAY Z X 01/09/2020 00:10:50 LOVE STORY TAYLOR SWIFT X 01/09/2020 00:14:23 WHAT'S ON YOUR MIND INFORMATION SOCIETY WARNER X 01/09/2020 00:18:56 BECAUSE OF YOU NE YO X 01/09/2020 00:22:42 OVER MY HEAD THE FRAY X 01/09/2020 00:26:34 BURN ELLIE GOULDING X 01/09/2020 00:30:16 NOTORIUS (86) DURAN DURAN - X 01/09/2020 00:34:13 HERE WITH ME MARSHMELLO X 01/09/2020 00:36:48 IRIS GOO GOO DOLLS EMI X 01/09/2020 00:39:24 SAY GOODBYE CHRIS BROWN X 01/09/2020 00:43:09 OVER MY SHOULDER MIKE & THE MECHANICS X 01/09/2020 00:46:40 DONE FOR ME CHARLIE PUTH FEAT. KEHLANI X 01/09/2020 00:49:15 SOMETHING ABOUT YOU LEVEL 42 X 01/09/2020 00:52:50 MAGIC COLDPLAY X 01/09/2020 00:56:34 RADIO GAGA QUEEN - X 01/09/2020 01:02:08 UM DIA DE CADA VEZ TIHUANA X 01/09/2020 01:05:51 DEATH BED POWFU X 01/09/2020 01:08:37 TEN THOUSAND HOURS DAN + SHAY FEAT.