Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use by Pediatric Specialty Outpatients

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Submission: TGA Transparency Review

Ken McLeod , I 3 15 March 2011 TO: THE TRANSPARANCY REVIEW PANEL: [email protected] THERAPEUTIC GOODS ADMINISTRATION • Dear Professor Pearce Re: TGA Review: "Getting Information about Medicines and Medical Devices Made Easier" I refer to the Review of the TGA currently being conducted, and that I notice that I might have missed the date for final submissions. I request that this submission be accepted, as it relates to a matter of public importance; that is the implied endorsement of dangerous and ineffective medical devices by the TGA. I note that the Parliamentary Secretary for Health and Ageing, Catherine King, has announced that, "It is now easy for consumers to find 0 product name and the ingredients, de toils about the company, the date a product was approved for use in Australia and importantly any warningsabout the use of the product." 1 .1 read a recent report by Choice magazine on pharmacies. 2 That prompted me to go my local pharmacy last week, and what did I find? Ear candles! I was surprised to see that medical devices that are known to be dangerous and ineffective are on sale at a pharmacy which is part of a national chain, and is supposed to abide by the Pharmacy Guild's Code of Conduct. In fact, "surprised" does not cover my reaction; I was disgusted, horrified, and angry that these gadgets could be on sale legally. I was even more surprised, disgusted, horrified, and angry that these gadgets carried an ARTG number. To the innocent bystander, an ARTG number implies an endorsement from the TGA, after supposedly passing tests for safety and efficacy. -

AGENCY PROCEDURE for RULE MAKING 7.1(17A) Adoption by Reference

IAC 6/30/10 Professional Licensure[645] Analysis, p.1 PROFESSIONAL LICENSURE DIVISION[645] Created within the Department of Public Health[641] by 1986 Iowa Acts, chapter 1245. Prior to 7/29/87, for Chs. 20 to 22 see Health Department[470] Chs. 152 to 154. CHAPTERS 1 to 3 Reserved CHAPTER 4 BOARD ADMINISTRATIVE PROCESSES 4.1(17A) Definitions 4.2(17A) Purpose of board 4.3(17A,147,272C) Organization of board and proceedings 4.4(17A) Official communications 4.5(17A) Office hours 4.6(21) Public meetings 4.7(147) Licensure by reciprocal agreement 4.8(147) Duplicate certificate or wallet card 4.9(147) Reissued certificate or wallet card 4.10(17A,147,272C) License denial 4.11(272C) Audit of continuing education report 4.12(272C) Automatic exemption 4.13(272C) Grounds for disciplinary action 4.14(272C) Continuing education exemption for disability or illness 4.15(147,272C) Order for physical, mental, or clinical competency examination or alcohol or drug screening 4.16(252J,261,272D) Noncompliance rules regarding child support, loan repayment and nonpayment of state debt CHAPTER 5 FEES 5.1(147,152D) Athletic training license fees 5.2(147,158) Barbering license fees 5.3(147,154D) Behavioral science license fees 5.4(151) Chiropractic license fees 5.5(147,157) Cosmetology arts and sciences license fees 5.6(147,152A) Dietetics license fees 5.7(147,154A) Hearing aid dispensers license fees 5.8(147) Massage therapy license fees 5.9(147,156) Mortuary science license fees 5.10(147,155) Nursing home administrators license fees 5.11(147,148B) Occupational -

The Ear Candling Position Statement

audiologynow winter06 Public Arena/ Ear Candling for Cerumen Removal iven a recent trend toward removed from the inner ear, the facial sinuses, or even the brain G naturopathicicself-treatment, itself, all of which are somehow connected to the canal. significant attention has been afforded to the practice of ear candling for cerumen removal (Harris and Sullivan, 1999). The practice of ear candling has become popular as an alternative therapy worldwide. Some promoters say it is an ancient treatment that can cure a number Kate Moore of medical problems, while health regulatory bodies around the world have research to show that the procedure has no proven medical benefits, and can be very dangerous. So what relevance does it have to audiology and how can we learn about it and inform our clients? I started, as we so often do today, with Google. The internet is a wonderful resource, providing a wealth of Above/ Could these be ear candles, or some new paint brushes for information on every topic known to man. It is a fabulous tool as long his birthday? as users understand that all the information they read may not be true. It is comforting that the first 2 hits when googling “ear candle” Ear candling claims to: tell me that it is not such a good idea, however the majority of the next 400,000 proceed to educate me on how it will make me a better • relieve sinus pressure and pain • cleanse the ear canal person, how I can do it myself, and where to buy the appropriate • assist lymphatic circulation • improve hearing beeswax. -

Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Corporate Medical Policy Complementary and Alternative Medicine File Name: complementary_and_alternative_medicine Origination: 12/2007 Last CAP Review: 2/2021 Next CAP Review: 2/2022 Last Review: 2/2021 Description of Procedure or Service The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Medicine (NCCIH), a component of the National Institutes of Health, defines complementary, alternative medicine (CAM) as a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional or allopathic medicine. While some scientific evidence exists regarding some CAM therapies, for most there are key questions that are yet to be answered through well-designed scientific studies-questions such as whether these therapies are safe and whether they work for the diseases or medical conditions for which they are used. Complementary medicine is used together with conventional medicine. Complementary medicine proposes to add to a proven medical treatment. Alternative medicine is used in place of conventional medicine. Alternative means the proposed method would possibly replace an already proven and accepted medical intervention. NCCIM classifies CAM therapies into 5 categories or domains: • Whole Medical Systems. These alternative medical systems are built upon complete systems of theory and practice. These systems have evolved apart from, and earlier than, the conventional medical approach used in the U.S. Examples include: homeopathic and naturopathic medicine, Traditional Chinese Medicine, Ayurveda, Macrobiotics, Naprapathy and Polarity Therapy. • Mind-Body Medicine. Mind-body interventions use a variety of techniques designed to enhance the mind’s capacity to affect bodily functions and symptoms. Some techniques have become part of mainstream practice, such as patient support groups and cognitive-behavioral therapy. -

Ear Candling Tales and Adventures

EAR CANDLING TALES AND ADVENTURES A PRACTICAL GUIDE TO EAR CANDLING HOW TO DO IT, WHAT IT HAS DONE AND HOW IT WORKS! Written By: Greg Webb Registered Massage Therapist Certified Touch For Health Instructor Ear Candling Instructor Domestic and International Supplier of Ear Candles Since 1993 Table of Contents TOPIC PAGE NUMBER Introduction A. What is Ear Candling? ..................................................................3 B. Can it be done by yourself?............................................................4 C. What will you feel?........................................................................4 D. How many candles per treatment? ........................................................ 5 E. Testimonials ........................................................................... 9-14 F. How it works, logic and speculation! ......................................... 14 G. What is found inside the Ear Candle? ......................................... 14 H. Supplies required ........................................................................16 I. Ear Candling instructions ......................................................17-20 J. Other info ...............................................................................20-22 K. Summary ....................................................................................23 Contact Information for the Author: Greg Webb 3035 – 26th Street S.W. Calgary, Alberta Canada T3E 2B6 Ph (403) 242-7647 Fax (403) 242-7680 Email: [email protected] 2 CANDLING WHAT IS IT? WHAT -

Doc Harmony, Ear Candles and the FDA

Doc Harmony, Ear Candles and the FDA Ear Candles - What is the Truth? I hope by now that you have heard about those crazy, wacky things called Ear Candles … and, boy have they caused quite the commotion! In this blog, I am going to review and examine the debate surrounding ear candles, prove what the legal status of ear candles are in the USA, clarify exactly what ear candles do and do not do and I am going to share with you why and how to use ear candles. Of course, in the end it is up to you to decide for yourself about ear candles. I am Doc Harmony and for the last 26 years, I have dedicated my professional, and a lot of my personal life, to Ear Candles. Why? In 1992, my son was very ill with ear infections for about 1 year. After being prescribed another batch of antibiotics, he began vomiting up the medicine. I had had enough. At this time, I went to Dr. Berryhill (our family Naturopath since I was 16) and he introduced me to ear candles. Of course, I thought this was a hoax but at this point in life, I had no other options. I wanted my son to be healthy! So I used 4 ear candles on my son and he has not had another ear infection to this day. Simultaneously, Dr. Berryhill called on me numerous times to encourage me to make and sell ear candles. I took his advice and thus began Harmony Cone Ear Candles. Life was good, handcrafting and selling ear candles, raising my family, working and living together sustainably upon the land. -

Sports Therapy and Personal Training

Holistic Therapy Massage Sports Injury Personal Training Education www.physique.co.uk Welcome Physique Lifestyle offers a comprehensive product Contents range for today’s student and modern therapist in holistic therapy, massage, sports therapy and personal training. Stone Therapy ................ 3 Reflexology ................... 3 We know it’s hard to get started *Buy any 3 in therapy so we’ve put together and get Seated Acupressure ........ 4 some fantastic products and th packages; many at : 4 FREE Ear Candling ............... 4 Massage ........................ 5 The full “Lifestyle” product range can be seen at www.physique.co.uk with a dedicated “Lifestyle” Couches ......................... 7 section, with up to date products sourced from Sports Therapy ............... 8 around the world to give you the very best product choice. Personal Training ......... 10 Yoga & Pilates .............. 12 If you have any questions please contact us either at [email protected] or call 0870 60 70 381 Models .......................... 13 Thank you for choosing us, we know you have a Starter Packs ................. 14 choice and we will do everything we can to fulfil Education ..................... 15 your requirements. Physique Lifestyle Team COUCHES p8 OILS LOTIONS COUCH WAXES COVER p6 p5 STARTER PACKS p10 p15 Learn-BY-Doing Workshop 2 SALES 0870 60 70 381 ORDER ON-LINE www.physique.co.uk Stone Therapy Stone Therapy Kit 1:- Medium Stone Kit Kit 2:- Large Stone Kit Natural Basalt Stones, sourced from the 46 Piece Set consists of 38 Basalt Stones 60 Piece Set consists of 52 Basalt Stones river beds in Peru and Mexico, they are of various sizes, 7 piece chakra set and a of various sizes, 7 piece chakra set and a truly natural and original. -

C+D P14 Update March 14.Indd

CPD Zone Update PREMIUM CPD CONTENT FOR £1 PER WEEK Buy UPDATEPLUS for £52+VAT chemistanddruggist.co.uk/update Visit chemistanddruggist.co.uk/update-plus for full details This module covers: March ● Distinguishing alternative therapies from Clinical: Alternative remedies and UPDATE conventional ones interactions month ● Evidence behind and effects of common ● CAM regulations March 7* Clinical therapies such as chiropractic and ear candling ● Alternative therapies March 14 ● The claims behind reiki and advice to give ● Common interactions March 21 Module 1741 patients ● How to help patients make an informed Practice: Skill-mix in the decision on alternative therapies pharmacy March 28 *Online-only for Update Plus subscribers Alternative therapies Nancy Kane 2010 found that, while it had some short- and medium-term benefit for pain and disability Alternative therapies are widely used and in people with lower back pain, there was no readily available in the UK. Most pharmacies good-quality evidence that it was any better or stock some kind of remedy that would not worse than lifestyle changes. Chiropractic is be considered mainstream medicine, and regularly used to treat a variety of conditions many high streets feature acupuncturists such as shoulder pain, epicondylitis (tennis and chiropractors. But are they worth using? elbow), osteoarthritis and headache, but since And how should you go about advising and there is no conclusive evidence that it is supporting patients who would like to try effective for these or any other indications, it something outside of conventional medicine? cannot ethically be recommended. There are many definitions of what Patients should also bear in mind that constitutes alternative medicine, but chiropractic can have substantial adverse the simplest is perhaps to include effects. -

Holistic Health Naturopathy Services

MALDIVES RANGALI ISLAND HOLISTIC HEALTH NATUROPATHY SERVICES Holistic Health incorporates the principles of Naturopathy or Natural Healing and combines modern science with nature using a range of different healing modalities such as Nutritional Therapy, Herbal Medicine, Iridology, Acupuncture, Reiki, and Massage. Naturopathy focusses on prevention and education through holistic practices, allowing us to stimulate the vital healing force of nature which lies within each of us. Our resident Naturopath can work with you towards your desired goals, such as weight loss, a specific health concern, detoxification or de-stress. NATUROPATHY NUTRITION IRIDOLOGY CONSULTATION CONSULTATION 30 mins 90 mins 60 mins $79 $169 $149 Iridology asserts that the within the body. Through Based on the philosophy prevent disease to Whether you have specific fibre structures in the an iridology session, that the body has the maximise your energy concerns or are just keen to iris represent a map of our resident naturopath innate ability to heal and wellbeing. You will learn about healthy eating, our your inherited resiliency, can reveal your physical itself, naturopathy be empowered to make Naturopath will look in detail or how well your body constitution and uncover uses a combination of choices to improve your at your daily food intake and can withstand or recover these strengths and therapies aimed at health and your life. provide an objective look at your from negative influences. weaknesses providing restoring and promoting This consultation dietary habits. Any health issues The pigmentations you with the knowledge health naturally. includes written can also be addressed using the indicate how your body to effectively approach During this in-depth recommendations, an concept of ‘food as medicine’ is most likely to react health challenges or consultation, our iridology assessment and recommendations will be to stress and unhealthy employ preventative naturopath will assess and recommendations given for you to make the right influences. -

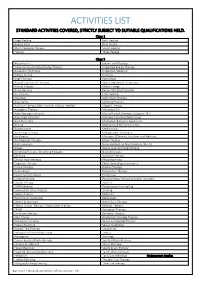

Activities List Standard Activities Covered, Strictly Subject to Suitable Qualifications Held

ACTIVITIES LIST STANDARD ACTIVITIES COVERED, STRICTLY SUBJECT TO SUITABLE QUALIFICATIONS HELD. Class 1 Angel Healing Reiki Healing Angelic Reiki Reiki Master Block Clearance Therapy Sound Healing Healing Theta Healing Class 2 Acupressure Indian Head Massage Advanced Sound-Wave Energy Therapy Integrated Energy Therapy Alexander Technique Integrative Medicine Allergy Testing Iridology Angel Therapy Kinesiology Animal Essential Oil Therapy Kinesis Myofascial Integration Animal Therapy Kinetic Energy Aromatherapy Kirlian / Bio Electrographic Art Therapy Life Coaching Astrology Light Touch Therapy Aura-Soma Lightning Process Auricular Therapy (Non-invasive, without needles) Magnet Therapy Autogenic Therapy Mahayana Chi Baby Massage Instructor Manual Lymph Drainage Category 1 & 2 Baby Yoga Instructor Massage (including deep tissue) Bach Remedies Meditation & Psychic Awareness Bi Aura Meditation & Mind Instruction Bioresonance Mediumship Bio Energy Therapy Metamorphic Technique Bio Kinetics Ministers, Officients, Intuitives and Mediums Bio Magnetic Therapy Music Therapy Body Harmony Naturopathy (Live blood analysis Class 3) Bowen Neuro Linguistic Programming Breathing Therapy / Breathing Massage Neuroflexology Chi Kung Nutrition Therapy Clinical Hypnotherapy Phytobiophysics Cognitive Therapy Pilates (including Gyrotonics) Colour Therapy Polarity Therapy Counselling Provocative Therapy Cranio Sacral Therapy Psychology Creative Writing Psychotherapy (including Jungian Analysts) Crystal Therapy Psych-K DORN Method Psychosexual Counselling Dowsing -

Download a PDF of “The Authenticity, Usage and Efficacy of Ear Candles.”

The Authenticity, Usage and Efficacy of Ear Candles By Harmony Cone 2007 Copyright Harmony Cone ©2007 ABSTRACT SEPARATING FACT from FICTION The Authenticity, Usage and Efficacy of Ear Candles © Clayton College of Natural Health – Douglasville, 2007 Advisor: Dr. Janice Martin Historical reports of ear candling and the use of ear candles are prevalent in a wide and diverse variety of cultures, including Europe, India, Japan and the United States. Ear candles have seen a resurgence in popularity within the last 10 years. FACT vs. FICTION The reality is that Ear candles are an incredible holistic wellness modality. In fact, most holistic therapies have some “energic” affect on our body’s cellular electrical system, including the meridian and reflexology systems, which overlay our subtle nadis human system. The purpose of this research is to discover the originations of ear candles, to establish standards of safety for ear candles, and to reveal how ear candles TRULY work. Regrettably, to date, there have been few scientific studies to validate these remarkable energic shifts in the human body, although we are preparing to conduct some studies to prove the efficacy of this holistic modality. The resulting true effects of holistic ear candling have been documented by a few manufacturers and some practitioners of alternative wellness therapies. It is uniformly agreed, that various unbalanced health symptoms usually dissipate within a day or two after a holistic ear candling session. Further validation of ear candles’ efficacy is seen by allowing the body to dissipate or reduce imbalanced health conditions, returning the body to its natural homeostatic balance. -

Informed Consent

Commentary Commentary The “other” informed consent Paul F Carey, DC Allan M Freedman, LLB Jean A Moss, DC President Professor President Canadian Chiropractic Canadian Memorial Canadian Memorial Protective Association Chiropractic College Chiropractic College Chiropractors have received a lot of information concern- addition, a chiropractor may practice alone or in a group ing the matter of “informed consent”. In some jurisdic- practice with other licensed health practitioners, i.e. mas- tions, as in the case of Ontario, chiropractors are legisla- sage therapists, kinesiologists, naturopaths, homeopaths, tively required to obtain informed consent from a patient etc. There are a number of variations to the type of practice prior to providing treatment. In all common law jurisdic- which may be conducted by a chiropractor and in what tions, provincial and state, the obligation has been imposed environment it might be carried on. The initial limitation upon health care practitioners, by courts of competent relating to practice may simply be the legislative authority jurisdiction, to obtain informed consent. The matter of the for what type of care might be provided by the chiropractor obligation to obtain informed consent has been well set- and under what conditions, as in the case of British Colum- tled. However, there may well be another area of informed bia which restricts dual licensure by a chiropractor. consent that is just as important but has not yet been fully There may not be a legislative authority restricting the acknowledged by health care practitioners. chiropractor from providing, as in the case in Ontario, care Who a chiropractor is, and what he or she does may not which is in the “public domain”.