From Michel Foucault to Mario Puzo: Using an Interdisciplinary Approach to Understand Ubran Immigration Then and Now

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recommended Reading 2010

American History 2010 Official Sponsors Ever worry that you’ve forgotten Dollar General, Dollar General Literacy everything you learned in school? Brush Foundation Wondering what to read in up with these American novels and history HarperCollins Publishers, Avon A, Harper your book club? books. Paperbacks, Harper Perennial Hyperion/Voice 1. Founding Mothers: The Women Simon & Schuster Let us help! Who Raised Our Nation by Cokie Unbridled Books Roberts $14.99 2. Moloka’i by Alan Brennert $14.99 3. The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dust Bowl by Park Road Books Timothy Egan $14.95 Park Road Shopping Center 4. The Devil in the White City 4139 Park Road Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Charlotte, NC 28209 Fair that Changed America by Erik Larson $15.00 5. The River of Doubt: Theodore Roosevelt's Darkest Journey by Candice Millard $15.00 6. Impatient with Desire by Gabrielle Burton $22.99 7. Ahab's Wife: Or, The Star-Gazer by Here are 4 lists of books that would Sena Jeter Naslund $15.95 make for great discussions at your 8. The Tea Rose by Jennifer Donnelly $14.95 book club, chosen by the officers of 9. All the President's Men by Carl the Charlotte chapter of the Women’s Bernstein and Bob Woodward $7.99 National Book Association 10. Assassination Vacation by Sarah Vowell $15.00 11. Confederates in the Attic: The Women’s National Book Association Dispatches from the Unfinished brings together people who share an Park Road Books carries all of these Civil War by Tony Horwitz $16.00 interest in books and reading. -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

![NOMINEES WINNING ALL / NONE [Updated Thru 88Th Awards (2/16)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4258/nominees-winning-all-none-updated-thru-88th-awards-2-16-1344258.webp)

NOMINEES WINNING ALL / NONE [Updated Thru 88Th Awards (2/16)]

NOMINEES WINNING ALL / NONE [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] WINNING ALL [Nominees with 2 or more competitive nominations, winning all] 4 Mark Berger 2 Mark Harris 4 Glen Robinson [plus 2 Sci/Tech Awards] 2 Helen Hayes 3 James Acheson 2 Rabbi Marvin Hier 3 Cecil Beaton 2 David Hildyard 3 Randall William Cook 2 Thomas Howard 3 Jacques-Yves Cousteau 2 Sarah Kernochan 3 Vernon Dixon 2 Barbara Kopple 3 Alex Funke 2 Ring Lardner, Jr. 3 Winton Hoch [plus 1 Sci/Tech Award] 2 Vivien Leigh 3 David MacMillan 2 Andrew Lockley 3 John Meehan (Art Director) 2 Branko Lustig 3 Giorgio Moroder 2 John Mollo 3 Carlo Rambaldi 2 Marc Norman 3 Jim Rygiel 2 Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy 3 United States Navy 2 Paramount Publix Studio Sound Dept. 3 Saul Zaentz [plus 1 Thalberg Award] 2 Paramount Studio [plus 1 Sci/Tech Award] 2 Ben Affleck 2 Mario Puzo 2 Robert Amram 2 Luise Rainer 2 Manuel Arango 2 Tony Richardson 2 Richard Attenborough 2 Stephen Rosenbaum 2 Karen Baker Landers 2 Albert S. Ruddy 2 Frank Borzage 2 Denis Sanders 2 Simon Chinn 2 Gustavo Santaolalla 2 Pierre Collings 2 Tom Scott 2 Mark Coulier 2 Robert Skotak 2 Michael Douglas 2 Kenneth Smith 2 Robert Epstein 2 Kevin Spacey 2 Freddie Francis 2 John Stears 2 Roger K. Furse 2 Hilary Swank 2 Harry Gerstad 2 John Truscott 2 Sheridan Gibney 2 Marcel Vertes 2 Mel Gibson 2 Christoph Waltz 2 Benjamin Glazer 2 Paul Weatherwax 2 William Goldman 2 Russell Williams II 2 Elizabeth Haffenden 2 Peter Young WINNING NONE [Nominees with 8 or more competitive nominations, winning none] 20 Kevin O'Connell 9 Ingmar Bergman [1 Thalberg Award] 16 Greg P. -

The Godfather Study Guide

OSCAR WINNER 1972: Best Picture Best Actor Best Adapted Screenplay TEACHERS’ NOTES This study guide is aimed at students of GCSE Media Studies, A’Level Film Studies and GNVO Media: Communication and Production (Intermediate and Advanced). Specific areas of study covered by the guide are those of genre, representation and the issue of violence in film. The Godfather: Certificate 18. Running Time 175 minutes. MAJOR CREDITS FOR THE GODFATHER The Godfather 1972 (Paramount) Producer: Albert S. Ruddy Director: Francis Coppola Screenplay: Mario Puzo, Francis Coppola Director of Photography: Gordon Willis Editors: William Reynolds, Peter Zinner Music: Nino Rota Art Director: Dean Tavoularis Cast: Marion Brando Al Pacino James Caan Richard Conte Robert Duvall Sterling Hayden Oscars 1972: Best Picture Best Actor (Marion Brando) Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar Nominations 1972: Best Director Best Supporting Actor (James Caan, Robert Duvall, Al Pacino) Best Music [later declared incligiblel Best Costume Design Best Editing Best Sound © Film Education 1 THE GODFATHER Coppola’s The Godfather was the direct descendant of dozens of gangster movies made with stars like Cagney and Edward C. Robinson. But there was a vital difference. Its examination of the Corleone family had a consistently human dimension that made the evil of the Mafia, who loved it for the wrong reasons, all the more horrendous. As a study of evil, it was all the better for assuming that such darkness emanated not from dyed-in-thewool villains but out of some of the family values we now most cherish. Added to that, of course, was the brilliance of its making, with Gordon Willis’ photography and Nino Rota’s score adding to Coppola’s fine orchestration of a terrific cast. -

Play Ball! Sports As Paradigms of Masucline Performance In

PLAY BALL! SPORTS AS PARADIGMS OF MASUCLINE PERFORMANCE IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY UNITED STATES by GEOFFREY AARON DOUGLAS (Under the Direction of DAVID SALTZ) ABSTRACT This study examines the culture of baseball and football as paradigms for masculine performativity. The goal is to establish a new way to examine the construction of masculine behavior in United State popular culture. After establishing how both baseball and football present distinct performative images of masculinity, a materialist reading of plays and films representing both sports will reveal how images of gender identity extend into the United States’ popular culture. INDEX WORDS: Gender, Masculinity, Performative Acts, Baseball, Football, Western, Film, Drama, Theatre, Babe Ruth, Grantland Rice, Jimmy Stewart, John Wayne, Walter Camp PLAY BALL! SPORTS AS PARADIGMS OF MASUCLINE PERFORMANCE IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY UNITED STATES by GEOFFREY AARON DOUGLAS BA, SAMFORD UNIVERSITY, 2006 MA, TEXAS STATE UNIVERSITY, 2011 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ATHENS, GEORGIA 2017 © 2017 GEOFFREY AARON DOUGLAS All Rights Reserved PLAY BALL! SPORTS AS PARADIGMS OF MASUCLINE PERFORMANCE IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY UNITED STATES by GEOFFREY AARON DOUGLAS Major Professor: David Saltz Committee: John Bray Jepkorir Rose Chepyator-Thompson Christopher Sieving Electronic Version Approved: Suzanne Barbour Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2017 iv DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my parents, who encourage me to love an accept everyone. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are too many people, without whose support and expertise this study would not exist, to list. -

Literature, CO Dime Novels

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 068 991 CS 200 241 AUTHOR Donelson, Ken, Ed. TITLE Adolescent Literature, Adolescent Reading and the English Class. INSTITUTION Arizona English Teachers Association, Tempe. PUB DATE Apr 72 NOTE 147p. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Road, Urbana, Ill. 61801 (Stock No. 33813, $1.75 non-member, $1.65 member) JOURNAL CIT Arizona English Bulletin; v14 n3 Apr 1972 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS *Adolescents; *English; English Curriculum; English Programs; Fiction; *Literature; *Reading Interests; Reading Material Selection; *Secondary Education; Teaching; Teenagers ABSTRACT This issue of the Arizona English Bulletin contains articles discussing literature that adolescents read and literature that they might be encouragedto read. Thus there are discussions both of literature specifically written for adolescents and the literature adolescents choose to read. The term adolescent is understood to include young people in grades five or six through ten or eleven. The articles are written by high school, college, and university teachers and discuss adolescent literature in general (e.g., Geraldine E. LaRoque's "A Bright and Promising Future for Adolescent Literature"), particular types of this literature (e.g., Nicholas J. Karolides' "Focus on Black Adolescents"), and particular books, (e.g., Beverly Haley's "'The Pigman'- -Use It1"). Also included is an extensive list of current books and articles on adolescent literature, adolescents' reading interests, and how these books relate to the teaching of English..The bibliography is divided into (1) general bibliographies,(2) histories and criticism of adolescent literature, CO dime novels, (4) adolescent literature before 1940, (5) reading interest studies, (6) modern adolescent literature, (7) adolescent books in the schools, and (8) comments about young people's reading. -

Catalogue 13 2 Catalogue 13

CATALOGUE 13 2 CATALOGUE 13 1904 Coolidge Ave., Altadena, California 91001 · Tel. (626) 297-7700 · [email protected] www.WhitmoreRareBooks.com Books may be reserved by email: [email protected] and by phone: (626) 297-7700 We welcome collectors and dealers to come visit our library by appointment at: 1904 Coolidge Ave., Altadena, CA 91001 For our complete inventory, including many first editions, signed books and other rare items, please visit our website at: www.WhitmoreRareBooks.com Follow us on social media! @WRareBooks @whitmorerarebooks whitmorerarebooks Catalogue 13 1. Ars Moriendi Ars Moriendi ex varijs sententijs collecta... Nurmberge (Nuremberg): J. Weissenburger, [1510]. Octavo (159 × 123 mm). Modern green morocco, spine lettered in gilt, boards single ruled in blind, edges green. Housed in a custom-made green slipcase. 14 woodcuts (the first repeated). Engraved bookplate of Catherine Macdonald to the front pastedown. Minor toning, cut close at foot with loss of portions of the decorative borders, a very good copy. First of three Latin editions printed by Weissenburger. The book derives from the Tractatus (or Speculum) Artis Bene Moriendi, composed in 1415 by an anonymous Dominican friar, probably at the request of the Council of Constance. The Ars Morienda is taken from the second chapter of that work, and deals with the five temptations that beset a dying man (lack of faith, despair, impatience, spiritual pride, and avarice), and how to avoid them. It was first published as a block book around 1450 in the Netherlands, and it was among the first books printed with movable type. It continued to be popular into the 16th century. -

Genre, Justice & Quentin Tarantino

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 11-6-2015 Genre, Justice & Quentin Tarantino Eric Michael Blake University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Scholar Commons Citation Blake, Eric Michael, "Genre, Justice & Quentin Tarantino" (2015). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/5911 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Genre, Justice, & Quentin Tarantino by Eric M. Blake A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies With a concentration in Film Studies College of Arts & Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Andrew Berish, Ph.D. Amy Rust, Ph.D. Daniel Belgrad, Ph.D. Date of Approval: October 23, 2015 Keywords: Cinema, Film, Film Studies, Realism, Postmodernism, Crime Film Copyright © 2015, Eric M. Blake TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................................................................................. ii Introduction ..................................................................................................................................1 -

Playboy Magazine Collection an Inventory

1 Playboy Magazine Collection An Inventory Creator: Hefner, Hugh (1926-2017) Title: Playboy Magazine Collection Dates: 1955-1994 Abstract: This collection consists of issues of Playboy and OUI magazines ranging from December 1955-June 2018. Playboy is unique among other erotic magazines of its time for its role as a purveyor of culture through political commentary, literature, and interviews with prominent activists, politicians, authors, and artists. The bulk of the collection dates from the 1960s-1970s and includes articles and interviews related to political debates such as the Cold War, Communism, Vietnam, the Civil Rights Movement, second-wave feminism, LGBTQ rights, and the depiction and consumption of the body. Researchers studying American Culture in the 1960s/70s, Gender & Sexuality, History of Advertising, and History of Photography will find this material of particular interest. Extent: 15 boxes, 6.25 linear feet Language: English Repository: Drew University Library, Madison NJ Biographical and History Note: Hugh Hefner, (April 9, 1926 – September 27, 2017), the founder and editor-in-chief of Playboy magazine, was known as a free speech activist, philanthropist, and proponent of sexual freedom. He founded Playboy magazine in 1953 with $1,000 seed money provided by his mother, Grace Hefner, a devout Methodist. The magazine quickly became known for its subversive visual, literary, and political content. Playboy is unique among other erotic magazines of the same time period for its role as a purveyor of culture through political commentary, literature, and interviews with prominent activists, politicians, authors, and artists. As a lifestyle magazine, Playboy curated and commodified the image of the modern bachelor of leisure. -

THE GODFATHER Part Two Screenplay by Mario Puzo And

THE GODFATHER Part Two Screenplay by Mario Puzo and Francis Ford Coppola SECOND DRAFT September 24, 1973 FADE IN: The Paramount Pictures logo is presented over a simple black background, as a single trumpet plays the familiar theme of a waltz. White lettering fades in: Mario Puzo's THE GODFATHER There is a pause, as the trumpet concludes, and there is the additional title: - Part Two - INT. DON CORLEONE'S OLD OFFICE - CLOSE VIEW ON MICHAEL CORLEONE - DAY standing impassively, like a young Prince, recently crowned King. CLOSE VIEW ON Michael's hand. ROCCO LAMPONE kisses his hand. Then it is taken away. We can SEE only the empty desk and chair of Michael's father, Vito Corleone. We HEAR, over this, very faintly a funeral dirge played in the distance, as THE VIEW MOVES SLOWLY CLOSER to the empty desk and chair. DISSOLVE TO: EXT. A SICILIAN LANDSCAPE - FULL VIEW - DAY We can barely make out the funeral procession passing over the burnt-brown of a dry river bed. The figures move slowly, seemingly from out of hundreds of years of the past. The MUSICIANS walking unsteadily on the rocky bed, their instruments harsh and blaring. They are followed by six young peasant men, carrying the crude wooden coffin on their shoulders. Then the widow, a strong large woman, dressed in black, and not accepting the arms of those walking with her. Behind her, not more than twenty relatives, few children and paisani continue alone behind the coffin. Suddenly, we HEAR the shots of the lupara, and the musicians stop their playing. -

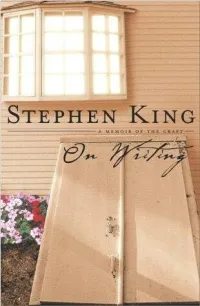

On Writing : a Memoir of the Craft / by Stephen King

l l SCRIBNER 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020 Visit us on the World Wide Web http://www.SimonSays.com Copyright © 2000 by Stephen King All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. SCRIBNER and design are trademarks of Macmillan Library Reference USA, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, the publisher of this work. DESIGNED BY ERICH HOBBING Set in Garamond No. 3 Library of Congress Publication data is available King, Stephen, 1947– On writing : a memoir of the craft / by Stephen King. p. cm. 1. King, Stephen, 1947– 2. Authors, American—20th century—Biography. 3. King, Stephen, 1947—Authorship. 4. Horror tales—Authorship. 5. Authorship. I. Title. PS3561.I483 Z475 2000 813'.54—dc21 00-030105 [B] ISBN 0-7432-1153-7 Author’s Note Unless otherwise attributed, all prose examples, both good and evil, were composed by the author. Permissions There Is a Mountain words and music by Donovan Leitch. Copyright © 1967 by Donovan (Music) Ltd. Administered by Peer International Corporation. Copyright renewed. International copyright secured. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Granpa Was a Carpenter by John Prine © Walden Music, Inc. (ASCAP). All rights administered by WB Music Corp. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Warner Bros. Publications U.S. Inc., Miami, FL 33014. Honesty’s the best policy. —Miguel de Cervantes Liars prosper. —Anonymous First Foreword In the early nineties (it might have been 1992, but it’s hard to remember when you’re having a good time) I joined a rock- and-roll band composed mostly of writers. -

N GUILTY MEN

ASIDE n GUILTY MEN ALEXANDER VOLOKHt And Abraham drew near, and said, Wilt thou also destroy the right- eous with the wicked? Peradventure there be fifty righteous within the city: wilt thou also destroy and not spare the place for the fifty righteous that are therein? That be far from thee to do after this manner, to slay the righteous with the wicked: and that the righteous should be as the wicked, that be far from thee: Shall not the Judge of all the earth do right? And the Lord said, If I find in Sodom fifty righteous within the city, then I will spare all the place for their sakes. And Abraham answered and said, Behold now, I have taken upon me to speak unto the Lord, which am but dust and ashes: Peradventure there shall lack five of the fifty righteous: wilt thou de- stroy all the city for lack of five? And he said, If I find there forty and five, I will not destroy it. And he spake unto him yet again, and said, Peradventure there shall be forty found there. And he said, I will not do it for forty's sake. t Policy Analyst for the Reason Public Policy Institute. For an embryonic version of this article, see ALEXANDER VOLOKH, PUNrITVE DAMAGES AND ENVIRONMENTAL LAW: RETHINKING THE IssuEs 20 n.91 (Reason Found. Policy Study No. 213, 1996). I am deeply indebted to my brother, Professor Eugene Volokh of UCLA Law School, without whose help and support this article would not have been possible.