1 Data Policies of Highly-Ranked Social Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D2.2: Research Data Exchange Solution

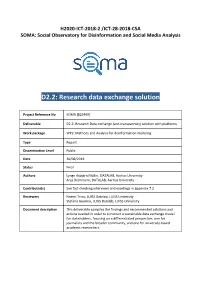

H2020-ICT-2018-2 /ICT-28-2018-CSA SOMA: Social Observatory for Disinformation and Social Media Analysis D2.2: Research data exchange solution Project Reference No SOMA [825469] Deliverable D2.2: Research Data exchange (and transparency) solution with platforms Work package WP2: Methods and Analysis for disinformation modeling Type Report Dissemination Level Public Date 30/08/2019 Status Final Authors Lynge Asbjørn Møller, DATALAB, Aarhus University Anja Bechmann, DATALAB, Aarhus University Contributor(s) See fact-checking interviews and meetings in appendix 7.2 Reviewers Noemi Trino, LUISS Datalab, LUISS University Stefano Guarino, LUISS Datalab, LUISS University Document description This deliverable compiles the findings and recommended solutions and actions needed in order to construct a sustainable data exchange model for stakeholders, focusing on a differentiated perspective, one for journalists and the broader community, and one for university-based academic researchers. SOMA-825469 D2.2: Research data exchange solution Document Revision History Version Date Modifications Introduced Modification Reason Modified by v0.1 28/08/2019 Consolidation of first DATALAB, Aarhus draft University v0.2 29/08/2019 Review LUISS Datalab, LUISS University v0.3 30/08/2019 Proofread DATALAB, Aarhus University v1.0 30/08/2019 Final version DATALAB, Aarhus University 30/08/2019 Page | 1 SOMA-825469 D2.2: Research data exchange solution Executive Summary This report provides an evaluation of current solutions for data transparency and exchange with social media platforms, an account of the historic obstacles and developments within the subject and a prioritized list of future scenarios and solutions for data access with social media platforms. The evaluation of current solutions and the historic accounts are based primarily on a systematic review of academic literature on the subject, expanded by an account on the most recent developments and solutions. -

A Comprehensive Analysis of the Journal Evaluation System in China

A comprehensive analysis of the journal evaluation system in China Ying HUANG1,2, Ruinan LI1, Lin ZHANG1,2,*, Gunnar SIVERTSEN3 1School of Information Management, Wuhan University, China 2Centre for R&D Monitoring (ECOOM) and Department of MSI, KU Leuven, Belgium 3Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation, Research and Education, Tøyen, Oslo, Norway Abstract Journal evaluation systems are important in science because they focus on the quality of how new results are critically reviewed and published. They are also important because the prestige and scientific impact of journals is given attention in research assessment and in career and funding systems. Journal evaluation has become increasingly important in China with the expansion of the country’s research and innovation system and its rise as a major contributor to global science. In this paper, we first describe the history and background for journal evaluation in China. Then, we systematically introduce and compare the most influential journal lists and indexing services in China. These are: the Chinese Science Citation Database (CSCD); the journal partition table (JPT); the AMI Comprehensive Evaluation Report (AMI); the Chinese STM Citation Report (CJCR); the “A Guide to the Core Journals of China” (GCJC); the Chinese Social Sciences Citation Index (CSSCI); and the World Academic Journal Clout Index (WAJCI). Some other lists published by government agencies, professional associations, and universities are briefly introduced as well. Thereby, the tradition and landscape of the journal evaluation system in China is comprehensively covered. Methods and practices are closely described and sometimes compared to how other countries assess and rank journals. Keywords: scientific journal; journal evaluation; peer review; bibliometrics 1 1. -

Downloaded Manually1

The Journal Coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: a Comparative Analysis Philippe Mongeon and Adèle Paul-Hus [email protected]; [email protected] Université de Montréal, École de bibliothéconomie et des sciences de l'information, C.P. 6128, Succ. Centre-Ville, H3C 3J7 Montréal, Qc, Canada Abstract Bibliometric methods are used in multiple fields for a variety of purposes, namely for research evaluation. Most bibliometric analyses have in common their data sources: Thomson Reuters’ Web of Science (WoS) and Elsevier’s Scopus. This research compares the journal coverage of both databases in terms of fields, countries and languages, using Ulrich’s extensive periodical directory as a base for comparison. Results indicate that the use of either WoS or Scopus for research evaluation may introduce biases that favor Natural Sciences and Engineering as well as Biomedical Research to the detriment of Social Sciences and Arts and Humanities. Similarly, English-language journals are overrepresented to the detriment of other languages. While both databases share these biases, their coverage differs substantially. As a consequence, the results of bibliometric analyses may vary depending on the database used. Keywords Bibliometrics, citations indexes, Scopus, Web of Science, research evaluation Introduction Bibliometric and scientometric methods have multiple and varied application realms, that goes from information science, sociology and history of science to research evaluation and scientific policy (Gingras, 2014). Large scale bibliometric research was made possible by the creation and development of the Science Citation Index (SCI) in 1963, which is now part of Web of Science (WoS) alongside two other indexes: the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) and the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI) (Wouters, 2006). -

A Bibliometric Visualization of the Economics and Sociology of Wealth Inequality: a World Apart?

Scientometrics (2019) 118:849–868 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-03000-z A bibliometric visualization of the economics and sociology of wealth inequality: a world apart? Philipp Korom1 Received: 20 April 2018 / Published online: 24 January 2019 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract Wealth inequality research is fragmented across diferent social science disciplines. This article explores the potential of interdisciplinary perspectives by investigating the thematic overlap between economic and sociological approaches to wealth inequality. To do so, we use the Web of Science citation database to identify pertinent articles on the topic of wealth inequality in each discipline (1990‒2017). On the basis of complete bibliographies of these selected articles, we construct co-citation networks and obtain thematic clusters. What becomes evident is a low thematic overlap: Economists explore the causes of wealth ine- quality based on mathematical models and study the interplay between inequality and eco- nomic growth. Sociologists focus mostly on wealth disparities between ethnic groups. The article identifes, however, a few instances of cross-disciplinary borrowing and the French economist Thomas Piketty as a novel advocate of interdisciplinarity in the feld. The pros- pects of an economics-cum-sociology of wealth inequality are discussed in the conclusion. Keywords Wealth inequality · Interdisciplinarity · Co-citation networks · VOSviewer · Piketty Rising disparities in ownership of private assets in the past few decades have become a matter of general concern that increasingly commands the attention of diferent disci- plines: Historians, for example, chronicle the evolution of wealth inequality from the dawn of mankind to modernity (Scheidel 2017); social geographers map the locational habits and trajectories of the super-rich (Forrest et al. -

POETICS Journal of Empirical Research on Culture, the Media and the Arts

POETICS Journal of Empirical Research on Culture, the Media and the Arts AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Audience p.2 • Impact Factor p.2 • Abstracting and Indexing p.2 • Editorial Board p.2 • Guide for Authors p.4 ISSN: 0304-422X DESCRIPTION . Poetics is an interdisciplinary journal of theoretical and empirical research on culture, the media and the arts. Particularly welcome are papers that make an original contribution to the major disciplines - sociology, psychology, media and communication studies, and economics - within which promising lines of research on culture, media and the arts have been developed. Poetics would be pleased to consider, for example, the following types of papers: • Sociological research on participation in the arts; media use and consumption; the conditions under which makers of cultural products operate; the functioning of institutions that make, distribute and/ or judge cultural products, arts and media policy; etc. • Psychological research on the cognitive processing of cultural products such as literary texts, films, theatrical performances, visual artworks; etc. • Media and communications research on the globalization of media production and consumption; the role and performance of journalism; the development of media and creative industries; the social uses of media; etc. • Economic research on the funding, costs and benefits of commercial and non-profit organizations in the fields of art and culture; choice behavior of audiences analysed from the viewpoint of the theory of lifestyles; the impact of economic institutions on the production or consumption of cultural goods; etc. The production and consumption of media, art and culture are highly complex and interrelated phenomena. -

Social Science & Medicine

SOCIAL SCIENCE & MEDICINE AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Audience p.2 • Impact Factor p.2 • Abstracting and Indexing p.2 • Editorial Board p.2 • Guide for Authors p.6 ISSN: 0277-9536 DESCRIPTION . Social Science & Medicine provides an international and interdisciplinary forum for the dissemination of social science research on health. We publish original research articles (both empirical and theoretical), reviews, position papers and commentaries on health issues, to inform current research, policy and practice in all areas of common interest to social scientists, health practitioners, and policy makers. The journal publishes material relevant to any aspect of health from a wide range of social science disciplines (anthropology, economics, epidemiology, geography, policy, psychology, and sociology), and material relevant to the social sciences from any of the professions concerned with physical and mental health, health care, clinical practice, and health policy and organization. We encourage material which is of general interest to an international readership. The journal publishes the following types of contribution: 1) Peer-reviewed original research articles and critical analytical reviews in any area of social science research relevant to health and healthcare. These papers may be up to 9000 words including abstract, tables, figures, references and (printed) appendices as well as the main text. Papers below this limit are preferred. 2) Systematic reviews and literature reviews of up to 15000 words including abstract, tables, figures, references and (printed) appendices as well as the main text. 3) Peer-reviewed short communications of findings on topical issues or published articles of between 2000 and 4000 words. -

The Latest Thinking About Metrics for Research Impact in the Social Sciences (White Paper)

A SAGE White Paper The Latest Thinking About Metrics for Research Impact in the Social Sciences SAGE Publishing Based on a workshop convened by SAGE Publishing including representatives from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, Altmetric, the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University, Clarivate Analytics, Google, New York University, School Dash, SciTech Strategies, the Social Science Research Council, and the University of Washington. www.sagepublishing.com Share your thoughts at socialsciencespace.com/impact or using #socialscienceimpact Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................2 Impact Metrics Workshop—February 2019 .................................................................3 Stakeholders ..................................................................................................................4 Academic Stakeholders—Individual ....................................................................................4 Academic Stakeholders—Institutional/Organizational ........................................................4 Societal Stakeholders ..........................................................................................................5 Commercial Stakeholders ...................................................................................................5 Academia .............................................................................................................................5 -

Social Scientists' Satisfaction with Data Reuse

Ixchel M. Faniel OCLC Research Adam Kriesberg University of Michigan Elizabeth Yakel University of Michigan Social Scientists’ Satisfaction with Data Reuse Note: This is a preprint of an article accepted for publication in Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology copyright © 2015. Abstract: Much of the recent research on digital data repositories has focused on assessing either the trustworthiness of the repository or quantifying the frequency of data reuse. Satisfaction with the data reuse experience, however, has not been widely studied. Drawing from the information systems and information science literatures, we develop a model to examine the relationship between data quality and data reusers’ satisfaction. Based on a survey of 1,480 journal article authors who cited Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) data in published papers from 2008 – 2012, we found several data quality attributes - completeness, accessibility ease of operation, and credibility – had significant positive associations with data reusers’ satisfaction. There was also a significant positive relationship between documentation quality and data reusers’ satisfaction. © 2015 OCLC Online Computer Library Center, Inc. 6565 Kilgour Place Dublin, Ohio 43017-3395 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Suggested citation: Faniel, I. M., Kriesberg, A. and Yakel, E. (2015). Social scientists' satisfaction with data reuse. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. doi: 10.1002/asi.23480 Social Scientists’ Satisfaction with Data Reuse 1 Introduction In the past decade, digital data repositories in a variety of disciplines have increased in number and scope (Hey, Tansley, & Tolle, 2009). -

A Bibliometric Analysis

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 4-5-2021 Trend of Research Visualization of Sociology of Education from 2001 to 2020: A Bibliometric Analysis Dr. Hazir Ullah Associate Professor, Department of Sociology, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan, [email protected] Mr. Muhammad Shoaib Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, University of Gujrat, Gujrat, Pakistan, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Archival Science Commons, Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, Educational Sociology Commons, Higher Education Commons, and the Theory, Knowledge and Science Commons Ullah, Dr. Hazir and Shoaib, Mr. Muhammad, "Trend of Research Visualization of Sociology of Education from 2001 to 2020: A Bibliometric Analysis" (2021). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 5172. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/5172 Trend of Research Visualization of Sociology of Education from 2001 to 2020: A Bibliometric Analysis First Author Dr. Hazir Ullah Associate Professor Department of Sociology Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan Email: [email protected] Second and Corresponding Author Muhammad Shoaib Assistant Professor Department of Sociology University of Gujrat, Gujrat, Pakistan Email: [email protected] 1 Trend of Research Visualization of Sociology of Education from 2001 to 2020: A Bibliometric Analysis Abstract This paper is designed to evaluate sociology of knowledge, sociology of education, educational sociology, sociology, and education using bibliometric analysis from 2001 to 2020. The main purpose is to consolidate the published scholarship on the sociology of education in the Web of Science indexed documents. -

Journal Rankings in Sociology

Journal Rankings in Sociology: Using the H Index with Google Scholar Jerry A. Jacobs1 Forthcoming in The American Sociologist 2016 Abstract There is considerable interest in the ranking of journals, given the intense pressure to place articles in the “top” journals. In this article, a new index, h, and a new source of data – Google Scholar – are introduced, and a number of advantages of this methodology to assessing journals are noted. This approach is attractive because it provides a more robust account of the scholarly enterprise than do the standard Journal Citation Reports. Readily available software enables do-it-yourself assessments of journals, including those not otherwise covered, and enable the journal selection process to become a research endeavor that identifies particular articles of interest. While some critics are skeptical about the visibility and impact of sociological research, the evidence presented here indicates that most sociology journals produce a steady stream of papers that garner considerable attention. While the position of individual journals varies across measures, there is a high degree commonality across these measurement approaches. A clear hierarchy of journals remains no matter what assessment metric is used. Moreover, data over time indicate that the hierarchy of journals is highly stable and self-perpetuating. Yet highly visible articles do appear in journals outside the set of elite journals. In short, the h index provides a more comprehensive picture of the output and noteworthy consequences of sociology journals than do than standard impact scores, even though the overall ranking of journals does not markedly change. 1 Corresponding Author; Department of Sociology and Population Studies Center, University of Pennsylvania, 3718 Locust Walk, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA; email: [email protected] Interest in journal rankings derives from many sources. -

Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences a PRACTICAL GUIDE

Petticrew / Assessing Adults with Intellecutal Disabilities 1405121106_01_pre-toc Final Proof page 3 4.8.2005 1:07am Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences A PRACTICAL GUIDE Mark Petticrew and Helen Roberts Petticrew / Assessing Adults with Intellecutal Disabilities 1405121106_01_pre-toc Final Proof page 1 4.8.2005 1:07am Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences Petticrew / Assessing Adults with Intellecutal Disabilities 1405121106_01_pre-toc Final Proof page 2 4.8.2005 1:07am Petticrew / Assessing Adults with Intellecutal Disabilities 1405121106_01_pre-toc Final Proof page 3 4.8.2005 1:07am Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences A PRACTICAL GUIDE Mark Petticrew and Helen Roberts Petticrew / Assessing Adults with Intellecutal Disabilities 1405121106_01_pre-toc Final Proof page 4 4.8.2005 1:07am ß 2006 by Mark Petticrew and Helen Roberts BLACKWELL PUBLISHING 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Mark Petticrew and Helen Roberts to be identified as the Authors of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2006 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd 1 2006 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Petticrew, Mark. Systematic reviews in the social sciences : a practical guide/Mark Petticrew and Helen Roberts. -

Journals in Social Work and Related Disciplines Manuscript Submission Information with Impact Factors, Five-Year Impact Factors, H-Index and G-Index

Journals in Social Work and Related Disciplines Manuscript Submission Information With Impact Factors, Five-Year Impact Factors, h-index and g-index Compiled by Patrick Leung, PhD Monit Cheung, PhD, LCSW Gerson & Sabina David Endowed Professor for Global Aging Mary R. Lewis Endowed Professor in Children and Youth Director, Office for International Social Work Education & Principal Investigator, Child Welfare Education Project [email protected] Director, Child & Family Center for Innovative Research [email protected] Graduate College of Social Work, University of Houston Houston, TX 77204-4013, USA First Published: September 1, 2004 Latest Edition: August 27, 2019 Red* (journal title followed by an asterisk) indicates that this journal is listed in the 2018 InCitiesTM Journal Citation Reports® (Published by Clarivate Analtics) within the category of “Social Work.” Based on JCR Social Science Edition, the Five-Year Impact Factor, current and past annual Impact Factors are also listed under each of these journals. Blue represents the Five-Year Impact Factor of the journal. The Five-Year Impact Factor is calculated by the following formula: [Citations in current year to articles/items published in the last five years] divided by [Total number of articles/items published in the last five years] Orange represents the h-index (Hirsch index) 1 and g-index of the journal 2. For journal ranking use, the h-index is defined as the h number of articles in the journal received at least h citations in the coverage years 3; the g-index is defined as the highest number g of papers that together received g2 or more citations 4.