Cms Convention on Migratory Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reproductive Strategy of Chrysichthys Nigrodigitatus (Lacepede, 1803) in a Natural Environment in the Nkam River, Littoral Cameroon

Hindawi International Journal of Zoology Volume 2020, Article ID 1378086, 8 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/1378086 Research Article Reproductive Strategy of Chrysichthys nigrodigitatus (Lacepede, 1803) in a Natural Environment in the Nkam River, Littoral Cameroon Claudine Tekounegning Tiogue´ ,1 Boddis Tsiguia Zebaze,2 Paul Zango,3 and Minette Eyango Tomedi-Tabi3 1Laboratory of Applied Ichthyology and Hydrobiology (LAIH), School of Wood, Water and Natural Resources (SWWNR), Faculty of Agronomy and Agricultural Sciences (FAAS), !e University of Dschang, P.O. Box 786, Ebolowa Antenna, Dschang, Cameroon 2Laboratory of Applied Ichthyology and Hydrobiology (LAIH), Department of Animal Productions, Faculty of Agronomy and Agricultural Sciences (FAAS), !e University of Dschang, P.O. Box 222, Dschang, Cameroon 3Laboratory for Aquaculture and Demography of Fisheries Resources (LADFR), Departement of Aquaculture, Institute of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences of Yabassi (IFAS), !e University of Douala, P.O. Box 2701, Douala, Cameroon Correspondence should be addressed to Claudine Tekounegning Tiogue´; [email protected] Received 30 July 2019; Accepted 20 December 2019; Published 15 February 2020 Academic Editor: Cucco Copyright © 2020 Claudine Tekounegning Tiogue´ et al. (is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. A study on the reproductive strategy of Chrysichthys nigrodigitatus was conducted from October 2015 to August 2016, in the Nkam River in Yabassi, Littoral Region of Cameroon. For this purpose, 154 specimens of C. nigrodigitatus with total mean weight of 829.96 ± 829.58 g and total mean length of 367 ± 156 mm collected from artisanal fishermen were used. -

Minmap Region Du Littoral Synthese Des Donnees Sur La Base Des Informations Recueillies

MINMAP REGION DU LITTORAL SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de N° Désignation des MO/MOD Montant des Marchés N° page Marchés 1 Communauté Urbaine de de Douala 94 89 179 421 671 3 2 Communité Urbaine d'édéa 5 89 000 000 14 3 Communité Urbaine de Nkongsamba 6 198 774 344 15 4 Services déconcentrés Régionaux 17 718 555 000 16 Département du Moungo 5 Services déconcentrés départementaux 5 145 000 000 18 6 Commune de BARE BAKEM 2 57 000 000 18 7 Commune de BONALEA 3 85 500 000 19 8 Commune de DIBOMBARI 3 105 500 000 19 9 Commune de LOUM 16 445 395 149 19 10 Commune de MANJO 8 132 000 000 21 11 Commune de MBANGA 3 108 000 000 22 12 Commune de MELONG 12 173 500 000 22 13 Commune de NJOMBE PENJA 5 132 000 000 24 14 Commune d'EBONE 12 299 500 000 25 15 Commune de MOMBO 3 77 000 000 26 16 Commune de NKONGSAMBA I 1 27 000 000 26 17 Commune de NKONGSAMBA II 3 59 250 000 27 18 Commune de NKONGSAMBA III 2 87 000 000 27 TOTAL Département 78 1 933 645 149 Département du Nkam 19 Services déconcentrés départementaux 12 232 596 000 28 20 Commune de NKONDJOCK 16 258 623 000 29 21 Commune de YABASSI 14 221 000 000 31 22 Commune de YINGUI 4 53 500 000 33 23 Commune de NDOBIAN 17 345 418 000 33 TOTAL Département 63 1 111 137 000 Département de la Sanaga Maritime 24 Services déconcentrés départementaux 8 90 960 000 36 25 Commune de Dibamba 3 72 000 000 37 26 Commune de Dizangue 5 88 500 000 37 27 Commune de MASSOCK 4 233 230 000 38 28 Commune de MOUANKO 15 582 770 000 38 29 Commune de NDOM 12 339 237 000 40 Nbre de N° Désignation -

CAMEROON COVID-19 Outbreak Anticipatory Briefing Note – 27 March 2020

CAMEROON COVID-19 outbreak Anticipatory briefing note – 27 March 2020 Anticipated crisis impact Key figures across the country • Cameroon has 54 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Central Region, Littoral Region and West Region as of 350,000 23 March 2020. (US Embassy) The first positive case was confirmed on 6 March 2020. displaced people face limited access to basic services and living in overcrowded conditions • Cameroon’s Ministry of Public Health has developed a preparedness plan for COVID-19, including active surveillance at points of entry, in-country diagnostic capacity at the national reference laboratory, and designated isolation and treatment centres. WHO and the U.S. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention Food Insecurity and malnutrition The Far North region is most affected by food (D) are providing technical support and are closely monitoring the situation in Cameroon. (US Embassy) insecurity. SAM exceeds the alert threshold of 1%. • The Cameroonian Prime Minister has announced that from 18 March all land, sea, and air borders are closed until further notice due to COVID-19. (US Embassy) (Journal de Cameroon, 18/03/2020) Vulnerable groups • Isolation and treatment centres have been set up for confirmed cases of COVID-19 at: immunocompromised people, displaced population, - Yaoundé Central Hospital, for Central Region, malnourished children, pregnant women and elders. - Laquintinie Hospital in Douala, for Littoral Region, - Garoua Regional Hospital, for North Region, National Cameroon’s Ministry of Public Health is leading the - Kribi District Hospital, for South Region (US Embassy) response capacity preparedness plan for COVID-19 across the country • No data is available regarding a preparedness plan in the Far North Region, where more than 100,000 WHO and the U.S. -

MINMAP Région Du Littoral

MINMAP Région du Littoral SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de Montant des N° Désignation des MO/MOD N° Page Marchés Marchés 1 Communauté Urbaine d'Edéa 6 1 747 550 008 3 2 Services déconcentrés Régionaux 10 534 821 000 4 TOTAL 16 2 282 371 008 Département du Wouri 3 Services déconcentrés départementaux 6 246 700 000 5 4 Commune de Douala 1 9 370 778 000 5 5 Commune de Douala 2 9 752 778 000 6 6 Commune de Douala 3 12 273 778 000 8 7 Commune de Douala 4 10 278 778 000 9 8 Commune de Douala 5 10 204 605 268 10 9 Commune de Douala 6 10 243 778 000 11 TOTAL 66 2 371 195 268 Département du Moungo 10 Services déconcentrés départementaux 10 159 560 000 12 11 Commune de Bare Bakem 9 234 893 804 13 12 Commune de Bonalea 11 274 397 840 14 13 Commune de Dibombari 11 267 278 000 15 14 Commune de Loum 12 228 397 903 16 15 Commune de Manjo 8 160 940 286 18 16 Commune de Mbanga 10 228 455 858 19 17 Commune de Melong 17 291 778 000 20 18 Commune de Njombe Penja 17 427 728 000 21 19 Commune d'Ebone 10 190 778 000 23 20 Commune de Mombo 9 163 878 000 24 21 Commune de Nkongsamba I 7 161 000 000 25 22 Commune de Nkongsamba II 6 172 768 640 25 23 Commune de Nkongsamba III 9 195 278 000 26 TOTAL 146 3 157 132 331 Département de la Sanaga Maritime 24 Services déconcentrés départementaux 10 214 167 000 27 25 Commune de Dibamba 14 358 471 384 28 26 Commune de Dizangue 13 252 678 000 29 27 Commune de Massock 16 319 090 512 30 28 Commune de Mouanko 9 251 001 000 31 29 Commune de Ndom 17 340 778 000 31 30 Commune de Ngambe 9 235 -

Impact Assessment on By-Catch Artisanal Fisheries: Sea Turtles And

quac d A ul n tu a r e s e J i o r u e r h n Ayissi and Jiofack, Fish Aquac J 2014, 5:3 s i a F l Fisheries and Aquaculture Journal DOI: 10.4172/ 2150-3508.1000099 ISSN: 2150-3508 Research Article Open Access Impact Assessment on By-catch Artisanal Fisheries: Sea Turtles and Mammals in Cameroon, West Africa Ayissi I1,2,3,4,* and Jiofack TJE5 1University of Abdelmalek Essaâdi, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Tetouan 2121, Morocco 2Cameroon Marine Biology Association, Morocco 3Specialized Research Center for Marine Ecosystems in Kribi-Cameroon, Cameroon 4Institute of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences (ISH) at Yabassi, University of Douala, PO Box 2701, Douala, Cameroon 5 Sub-Regional School and Postdoctoral Water Development and Integrated Management of Forests and Tropical Territories, Kinshasa, RDC, Congo *Corresponding author: Ayissi I, University of Abdelmalek Essaâdi, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Tetouan 2121, Morocco, Tel: +237 97350175; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: January 20, 2014; Accepted date: July 09, 2014; Published date: July 16, 2014 Copyright: © 2014 Ayissi I, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract The by-catch assessment has been carried out along Cameroon coastline to map artisanal fishing effort and quantify impact of by-catch on sea turtles and marine mammals during three months from June to September 2011 and specific objectives include: - To interview fishermen in various fishing villages or ports in Cameroon regarding fishing effort and catch. -

Ancestral Art of Gabon from the Collections of the Barbier-Mueller

ancestral art ofgabon previously published Masques d'Afrique Art ofthe Salomon Islands future publications Art ofNew Guinea Art ofthe Ivory Coast Black Gold louis perrois ancestral art ofgabon from the collections ofthe barbier-mueiler museum photographs pierre-alain ferrazzini translation francine farr dallas museum ofart january 26 - june 15, 1986 los angeles county museum ofart august 28, 1986 - march 22, 1987 ISBN 2-88104-012-8 (ISBN 2-88104-011-X French Edition) contents Directors' Foreword ........................................................ 5 Preface. ................................................................. 7 Maps ,.. .. .. .. .. ...... .. .. .. .. .. 14 Introduction. ............................................................. 19 Chapter I: Eastern Gabon 35 Plates. ........................................................ 59 Chapter II: Southern and Central Gabon ....................................... 85 Plates 105 Chapter III: Northern Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, and Southem Cameroon ......... 133 Plates 155 Iliustrated Catalogue ofthe Collection 185 Index ofGeographical Names 227 Index ofPeoplcs 229 Index ofVernacular Names 231 Appendix 235 Bibliography 237 Directors' Foreword The extraordinarily diverse sculptural arts ofthe Dallas, under the auspices of the Smithsonian West African nation ofGabon vary in style from Institution). two-dimcnsional, highly stylized works to three dimensional, relatively naturalistic ones. AU, We are pleased to be able to present this exhibi however, reveal an intense connection with -

Economic and Social Importance of Fuelwood in Cameroon

52 International Forestry Review Vol.18(S1), 2016 Economic and social importance of fuelwood in Cameroon R. EBA’A ATYI1, J. NGOUHOUO POUFOUN1,4,5, J-P. MVONDO AWONO2, A. NGOUNGOURE MANJELI3 and R. SUFO KANKEU1,6 1Center for International forestry Research (CIFOR) 2The University of Dschang (Cameroon) 3Ministry of Forests and Wildlife (Cameroon) 4Bureau d’Economie Théorique et Appliquée (BETA), Université de Lorraine (France) 5Inra, AgroParisTech, Laboratoire d’Économie Forestière 6Laboratoire ESO, University of Maine (France) Email: [email protected] SUMMARY The study presented in this article focuses on firewood and charcoal in Cameroon. The study analyses subnational secondary data combined in some cases with additional collected data on firewood and charcoal consumption as well as their market prices. The findings estimate a total consumption of 2.2 million metric tons for firewood and 356,530 metric tons for charcoal in urban areas of Cameroon. Firewood and charcoal contribute to the GDP for an estimated amount of US$ 304 million representing 1.3% of the GDP of Cameroon. In addition, the sub-sector provides about 90,000 equivalent full time jobs while 80% of the people in Cameroon depend entirely on wood-energy for household energy supply. Unfortunately, there is no government policy to develop the wood-energy sub-sector. Keywords: wood-energy, firewood, charcoal, consumption, benefits, national economy Importance économique et sociale du bois-énergie au Cameroun R. EBA’A ATYI, J. NGOUHOUO POUFOUN, J-P. MVONDO AWONO, A. NGOUNGOURE MANJELI et R. SUFO KANKEU L’étude présentée dans cet article s’est intéressée au bois de feu et au charbon de bois au Cameroun. -

In Lower Sanaga Basin, Cameroon: an Ethnobiological Assessment

Mongabay.com Open Access Journal - Tropical Conservation Science Vol.6 (4):521-538, 2013 Research Article Conservation status of manatee (Trichechus senegalensis Link 1795) in Lower Sanaga Basin, Cameroon: An ethnobiological assessment. Theodore B. Mayaka1*, Hendriatha C. Awah1 and Gordon Ajonina2 1 Department of Animal Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Dschang, PO Box 67Dschang, Cameroon. Email: *[email protected], [email protected] 2Cameroon Wildlife Conservation Society (CWCS), Coastal Forests and Mangrove Programme Douala-Edea Project, BP 54, Mouanko, Littoral, Cameroon. Email:[email protected] * Corresponding author Abstract An ethnobiological survey of 174 local resource users was conducted in the Lower Sanaga Basin to assess the current conservation status of West African manatee (Trichechus senegalensis, Link 1795) within lakes, rivers, and coast (including mangroves, estuaries and lagoons). Using a multistage sampling design with semi-structured interviews, the study asked three main questions: (i) are manatees still present in Lower Sanaga Basin? (ii) If present, how are their numbers evolving with time? (iii) What are the main threats facing the manatee? Each of these questions led to the formulation and formal testing of a scientific hypothesis. The study outcome is as follows: (i)60% of respondents sighted manatees at least once a month, regardless of habitat type (rivers, lakes, or coast) and seasons (dry, rainy, or both); (ii) depending on habitat type, 69 to 100% of respondents perceived the trend in manatee numbers as either constant or increasing; the increasing trend was ascribed to low kill incidence (due either to increased awareness or lack of adequate equipment) and to high reproduction rate; and (iii) catches (directed or incidental) and habitat degradation (pollution) ranked in decreasing order as perceived threats to manatees. -

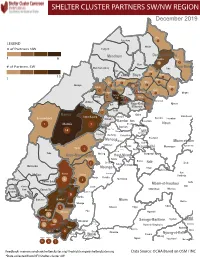

NW SW Presence Map Complete Copy

SHELTER CLUSTER PARTNERS SW/NWMap creation da tREGIONe: 06/12/2018 December 2019 Ako Furu-Awa 1 LEGEND Misaje # of Partners NW Fungom Menchum Donga-Mantung 1 6 Nkambe Nwa 3 1 Bum # of Partners SW Menchum-Valley Ndu Mayo-Banyo Wum Noni 1 Fundong Nkum 15 Boyo 1 1 Njinikom Kumbo Oku 1 Bafut 1 Belo Akwaya 1 3 1 Njikwa Bui Mbven 1 2 Mezam 2 Jakiri Mbengwi Babessi 1 Magba Bamenda Tubah 2 2 Bamenda Ndop Momo 6b 3 4 2 3 Bangourain Widikum Ngie Bamenda Bali 1 Ngo-Ketunjia Njimom Balikumbat Batibo Santa 2 Manyu Galim Upper Bayang Babadjou Malentouen Eyumodjock Wabane Koutaba Foumban Bambo7 tos Kouoptamo 1 Mamfe 7 Lebialem M ouda Noun Batcham Bafoussam Alou Fongo-Tongo 2e 14 Nkong-Ni BafouMssamif 1eir Fontem Dschang Penka-Michel Bamendjou Poumougne Foumbot MenouaFokoué Mbam-et-Kim Baham Djebem Santchou Bandja Batié Massangam Ngambé-Tikar Nguti Koung-Khi 1 Banka Bangou Kekem Toko Kupe-Manenguba Melong Haut-Nkam Bangangté Bafang Bana Bangem Banwa Bazou Baré-Bakem Ndé 1 Bakou Deuk Mundemba Nord-Makombé Moungo Tonga Makénéné Konye Nkongsamba 1er Kon Ndian Tombel Yambetta Manjo Nlonako Isangele 5 1 Nkondjock Dikome Balue Bafia Kumba Mbam-et-Inoubou Kombo Loum Kiiki Kombo Itindi Ekondo Titi Ndikiniméki Nitoukou Abedimo Meme Njombé-Penja 9 Mombo Idabato Bamusso Kumba 1 Nkam Bokito Kumba Mbanga 1 Yabassi Yingui Ndom Mbonge Muyuka Fiko Ngambé 6 Nyanon Lekié West-Coast Sanaga-Maritime Monatélé 5 Fako Dibombari Douala 55 Buea 5e Massock-Songloulou Evodoula Tiko Nguibassal Limbe1 Douala 4e Edéa 2e Okola Limbe 2 6 Douala Dibamba Limbe 3 Douala 6e Wou3rei Pouma Nyong-et-Kellé Douala 6e Dibang Limbe 1 Limbe 2 Limbe 3 Dizangué Ngwei Ngog-Mapubi Matomb Lobo 13 54 1 Feedback: [email protected]/ [email protected] Data Source: OCHA Based on OSM / INC *Data collected from NFI/Shelter cluster 4W. -

Gastropod Fauna of the Cameroonian Coasts

Helgol Mar Res (1999) 53:129–140 © Springer-Verlag and AWI 1999 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Klaus Bandel · Thorsten Kowalke Gastropod fauna of the Cameroonian coasts Received: 15 January 1999 / Accepted: 26 July 1999 Abstract Eighteen species of gastropods were encoun- flats become exposed. During high tide, most of the tered living near and within the large coastal swamps, mangrove is flooded up to the point where the influence mangrove forests, intertidal flats and the rocky shore of of salty water ends, and the flora is that of a freshwater the Cameroonian coast of the Atlantic Ocean. These re- regime. present members of the subclasses Neritimorpha, With the influence of brackish water, the number of Caenogastropoda, and Heterostropha. Within the Neriti- individuals of gastropod fauna increases as well as the morpha, representatives of the genera Nerita, Neritina, number of species, and changes in composition occur. and Neritilia could be distinguished by their radula Upstream of Douala harbour and on the flats that lead anatomy and ecology. Within the Caenogastropoda, rep- to the mangrove forest next to Douala airport the beach resentatives of the families Potamididae with Tympano- is covered with much driftwood and rubbish that lies on tonos and Planaxidae with Angiola are characterized by the landward side of the mangrove forest. Here, Me- their early ontogeny and ecology. The Pachymelaniidae lampus liberianus and Neritina rubricata are found as are recognized as an independent group and are intro- well as the Pachymelania fusca variety with granulated duced as a new family within the Cerithioidea. Littorini- sculpture that closely resembles Melanoides tubercu- morpha with Littorina, Assiminea and Potamopyrgus lata in shell shape. -

Molecular Detection of Simulium Damnosum S.L, Vector Of

Journal of Veterinary Research Advances Research Article ISSN: 2582-774X Open access Molecular detection of Simulium damnosum S.l , Vector of Onchocerca volvulus in Sanaga Maritime (Littoral-Cameroon) Sevidzem Silas Lendzele 1 and Hiol Victor Dermy 2 1Laboratoire d’EcologieVectorielle (LEV-IRET), Libreville, Gabon 2Department of Parasitology and Parasitological Diseases, School of Veterinary Medicine and Science, University of Ngaoundere, Ngaoundere, Cameroon Corresponding author: [email protected] Received on: 18/02/2021 Accepted on: 06/03/2021 Published on: 18/03/2021 ABSTRACT Aim: The study was aimed to identify Simulium species of Mouanko using molecular tools. Method and Materials: Simulium biting humans were aspirated using a sucking tube for molecular identification. Fifty female Simulium flies were caught using the mentioned technique. Results: Molecular genotyping revealed that the anthropophilic Simulium black flies caught were of the Simulium damnosums.l. complex. Conclusion: The presence of Simulium damnosum s.l . indicates the risk of ongoing onchocercosis transmission in the study area. Keywords: Simulium , sucking tube, genotyping, Mouanko . Cite This Article as : Lendzele SS and Dermy HV (2021). Molecular detection of Simulium damnosum S.l , Vector of Onchocerca volvulus in Sanaga Maritime (Littoral-Cameroon). J. Vet. Res. Adv. 03(01): 25-27. Introduction Materials and Methods Human onchocercosis remains a threat to the Description of study area lives of individuals living in some rural Fly collection was conducted in the littoral region communities of Cameroon. The WHO/APOC precisely in Mouanko (Latitude 3° 38' 00’’North and survey report of 2011 revealed >60% prevalence Longitude 9° 47' 00’' East). Mouanko is a coastal of onchocercosis in some foci of the Center 1, town in the Sanaga-Maritime division in the Littoral 2 and West region (Tekle et al., 2016). -

Living Under a Fluctuating Climate and a Drying Congo Basin

sustainability Article Living under a Fluctuating Climate and a Drying Congo Basin Denis Jean Sonwa 1,* , Mfochivé Oumarou Farikou 2, Gapia Martial 3 and Fiyo Losembe Félix 4 1 Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Yaoundé P. O. Box 2008 Messa, Cameroon 2 Department of Earth Science, University of Yaoundé 1, Yaoundé P. O. Box 812, Cameroon; [email protected] 3 Higher Institute of Rural Development (ISDR of Mbaïki), University of Bangui, Bangui P. O. Box 1450, Central African Republic (CAR); [email protected] 4 Faculty of Renewable Natural Resources Management, University of Kisangani, Kisangani P. O. Box 2012, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC); [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 22 December 2019; Accepted: 20 March 2020; Published: 7 April 2020 Abstract: Humid conditions and equatorial forest in the Congo Basin have allowed for the maintenance of significant biodiversity and carbon stock. The ecological services and products of this forest are of high importance, particularly for smallholders living in forest landscapes and watersheds. Unfortunately, in addition to deforestation and forest degradation, climate change/variability are impacting this region, including both forests and populations. We developed three case studies based on field observations in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, as well as information from the literature. Our key findings are: (1) the forest-related water cycle of the Congo Basin is not stable, and is gradually changing; (2) climate change is impacting the water cycle of the basin; and, (3) the slow modification of the water cycle is affecting livelihoods in the Congo Basin.