Kelsborrow Castle: a Late Prehistoric Promontory Fort

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gloucestershire Castles

Gloucestershire Archives Take One Castle Gloucestershire Castles The first castles in Gloucestershire were built soon after the Norman invasion of 1066. After the Battle of Hastings, the Normans had an urgent need to consolidate the land they had conquered and at the same time provide a secure political and military base to control the country. Castles were an ideal way to do this as not only did they secure newly won lands in military terms (acting as bases for troops and supply bases), they also served as a visible reminder to the local population of the ever-present power and threat of force of their new overlords. Early castles were usually one of three types; a ringwork, a motte or a motte & bailey; A Ringwork was a simple oval or circular earthwork formed of a ditch and bank. A motte was an artificially raised earthwork (made by piling up turf and soil) with a flat top on which was built a wooden tower or ‘keep’ and a protective palisade. A motte & bailey was a combination of a motte with a bailey or walled enclosure that usually but not always enclosed the motte. The keep was the strongest and securest part of a castle and was usually the main place of residence of the lord of the castle, although this changed over time. The name has a complex origin and stems from the Middle English term ‘kype’, meaning basket or cask, after the structure of the early keeps (which resembled tubes). The name ‘keep’ was only used from the 1500s onwards and the contemporary medieval term was ‘donjon’ (an apparent French corruption of the Latin dominarium) although turris, turris castri or magna turris (tower, castle tower and great tower respectively) were also used. -

Courtenay Arthur Ralegh Radford

Courtenay Arthur Ralegh Radford Book or Report Section Published Version Creative Commons: Attribution 3.0 (CC-BY) Open Access Gilchrist, R. (2013) Courtenay Arthur Ralegh Radford. In: Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the British Academy, XII. British Academy, pp. 341-358. ISBN 9780197265512 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/35690/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Published version at: http://www.britac.ac.uk/memoirs/12.cfm Publisher: British Academy All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online RALEGH RADFORD Pictured in 1957, in front of the ruins of the church at Glastonbury Abbey (Somerset). Reproduced with permission of English Heritage: NMR GLA/Pub/1/2. Courtenay Arthur Ralegh Radford 1900–1998 C. A. RALEGH RADFORD was one of the major figures of archaeology in the mid-twentieth century: his intellectual contribution to the discipline is rated by some as being comparable to giants such as Mortimer Wheeler, Christopher Hawkes and Gordon Childe.1 Radford is credited with help- ing to shape the field of medieval archaeology and in particular with inaug- urating study of the ‘Early Christian’ archaeology of western Britain. -

Medieval Castle

The Language of Autbority: The Expression of Status in the Scottish Medieval Castle M. Justin McGrail Deparment of Art History McGilI University Montréal March 1995 "A rhesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fu[filment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Am" O M. Justin McGrail. 1995 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1*u of Canada du Canada Aquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie SeMces seMces bibliographiques 395 Wellingîon Street 395, nie Wellingtm ûîtawaON K1AON4 OitawaON K1AON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une Licence non exclusive Licence dowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distniuer ou copies of this thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous papet or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels rnay be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. H. J. B6ker for his perserverance and guidance in the preparation and completion of this thesis. I would also like to recognise the tremendous support given by my family and friends over the course of this degree. -

The Iron Age Tom Moore

The Iron Age Tom Moore INTRODUCfiON In the twenty years since Alan Saville's (1984) review of the Iron Age in Gloucestershire much has happened in Iron-Age archaeology, both in the region and beyond.1 Saville's paper marked an important point in Iron-Age studies in Gloucestershire and was matched by an increasing level of research both regionally and nationally. The mid 1980s saw a number of discussions of the Iron Age in the county, including those by Cunliffe (1984b) and Darvill (1987), whilst reviews were conducted for Avon (Burrow 1987) and Somerset (Cunliffe 1982). At the same time significant advances and developments in British Iron-Age studies as a whole had a direct impact on how the period was viewed in the region. Richard Hingley's (1984) examination of the Iron-Age landscapes of Oxfordshire suggested a division between more integrated unenclosed communities in the Upper Thames Valley and isolated enclosure communities on the Cotswold uplands, arguing for very different social systems in the two areas. In contrast, Barry Cunliffe' s model ( 1984a; 1991 ), based on his work at Danebury, Hampshire, suggested a hierarchical Iron-Age society centred on hillforts directly influencing how hillforts and social organisation in the Cotswolds have been understood (Darvill1987; Saville 1984). Together these studies have set the agenda for how the 1st millennium BC in the region is regarded and their influence can be felt in more recent syntheses (e.g. Clarke 1993). Since 1984, however, our perception of Iron-Age societies has been radically altered. In particular, the role of hillforts as central places at the top of a hierarchical settlement pattern has been substantially challenged (Hill 1996). -

Cornish Archaeology 41–42 Hendhyscans Kernow 2002–3

© 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society CORNISH ARCHAEOLOGY 41–42 HENDHYSCANS KERNOW 2002–3 EDITORS GRAEME KIRKHAM AND PETER HERRING (Published 2006) CORNWALL ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society © COPYRIGHT CORNWALL ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY 2006 No part of this volume may be reproduced without permission of the Society and the relevant author ISSN 0070 024X Typesetting, printing and binding by Arrowsmith, Bristol © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society Contents Preface i HENRIETTA QUINNELL Reflections iii CHARLES THOMAS An Iron Age sword and mirror cist burial from Bryher, Isles of Scilly 1 CHARLES JOHNS Excavation of an Early Christian cemetery at Althea Library, Padstow 80 PRU MANNING and PETER STEAD Journeys to the Rock: archaeological investigations at Tregarrick Farm, Roche 107 DICK COLE and ANDY M JONES Chariots of fire: symbols and motifs on recent Iron Age metalwork finds in Cornwall 144 ANNA TYACKE Cornwall Archaeological Society – Devon Archaeological Society joint symposium 2003: 149 archaeology and the media PETER GATHERCOLE, JANE STANLEY and NICHOLAS THOMAS A medieval cross from Lidwell, Stoke Climsland 161 SAM TURNER Recent work by the Historic Environment Service, Cornwall County Council 165 Recent work in Cornwall by Exeter Archaeology 194 Obituary: R D Penhallurick 198 CHARLES THOMAS © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society Preface This double-volume of Cornish Archaeology marks the start of its fifth decade of publication. Your Editors and General Committee considered this milestone an appropriate point to review its presentation and initiate some changes to the style which has served us so well for the last four decades. The genesis of this style, with its hallmark yellow card cover, is described on a following page by our founding Editor, Professor Charles Thomas. -

Searching for Viking Age Fortresses with Automatic Landscape Classification and Feature Detection

remote sensing Article Searching for Viking Age Fortresses with Automatic Landscape Classification and Feature Detection David Stott 1,2, Søren Munch Kristiansen 2,3,* and Søren Michael Sindbæk 3 1 Department of Archaeological Science and Conservation, Moesgaard Museum, Moesgård Allé 20, 8270 Højbjerg, Denmark 2 Department of Geoscience, Aarhus University, Høegh-Guldbergs Gade 2, 8000 Aarhus C, Denmark 3 Center for Urban Network Evolutions (UrbNet), Aarhus University, Moesgård Allé 20, 8270 Højbjerg, Denmark * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +45-2338-2424 Received: 19 June 2019; Accepted: 25 July 2019; Published: 12 August 2019 Abstract: Across the world, cultural heritage is eradicated at an unprecedented rate by development, agriculture, and natural erosion. Remote sensing using airborne and satellite sensors is an essential tool for rapidly investigating human traces over large surfaces of our planet, but even large monumental structures may be visible as only faint indications on the surface. In this paper, we demonstrate the utility of a machine learning approach using airborne laser scanning data to address a “needle-in-a-haystack” problem, which involves the search for remnants of Viking ring fortresses throughout Denmark. First ring detection was applied using the Hough circle transformations and template matching, which detected 202,048 circular features in Denmark. This was reduced to 199 candidate sites by using their geometric properties and the application of machine learning techniques to classify the cultural and topographic context of the features. Two of these near perfectly circular features are convincing candidates for Viking Age fortresses, and two are candidates for either glacial landscape features or simple meteor craters. -

This Is an Open Access Document Downloaded from ORCA, Cardiff University's Institutional Repository

This is an Open Access document downloaded from ORCA, Cardiff University's institutional repository: http://orca.cf.ac.uk/98888/ This is the author’s version of a work that was submitted to / accepted for publication. Citation for final published version: Davis, Oliver 2017. Filling the gaps: the Iron Age in Cardiff and the Vale of Glamorgan. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 83 , pp. 325-256. 10.1017/ppr.2016.14 file Publishers page: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/ppr.2016.14 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/ppr.2016.14> Please note: Changes made as a result of publishing processes such as copy-editing, formatting and page numbers may not be reflected in this version. For the definitive version of this publication, please refer to the published source. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite this paper. This version is being made available in accordance with publisher policies. See http://orca.cf.ac.uk/policies.html for usage policies. Copyright and moral rights for publications made available in ORCA are retained by the copyright holders. FILLING THE GAPS: THE IRON AGE IN CARDIFF AND THE VALE OF GLAMORGAN Abstract Over the last 20 years interpretive approaches within Iron Age studies in Britain have moved from the national to the regional. This was an important development which challenged the notion that a unified, British, Iron Age ever existed. However, whilst this approach has allowed regional histories to be told in their own right there has been far too much focus on ‘key’ areas such as Wessex and Yorkshire. -

Conservation Study & Management Plan 2018 -2023

Conservation Study & Management Plan 2018 -2023 Drumanagh Promontory Fort, Co. Dublin Fingal Development Plan 2017 - 2023 www.fingal.ie Contents C Contents Illustrations i 1. Introduction 1 2. Study Area 2 3. Methodology 3 4. Statutory Protection 5 5. Understanding the Monument 6 6. Material Culture 49 7. Biodiversity 51 8. Results of Field Survey 53 9. Assessment of Significance 71 10. Issues 73 11. Opportunities 78 12. Policies 80 13. Actions & Objectives 82 14. Implementation 84 15. References 85 Appendix 1 - Cultural Heritage Sites 87 Appendix 2 - Topographical files 106 Appendix 3 - Ecology Study Recommendations 112 Drumanagh Conservation Study & Management Plan 2018 - 2023 Drumanagh Promontory Fort, Co. Dublin Christine Baker Image Courtesy of the Discovery Programme Drumanagh Conservation Study & Management Plan 2018 - 2023 View of erosion along the northern perimeter of Drumanagh Drumanagh and Lambay promontory forts (Westropp, 1921) Drumanagh Conservation Study & Management Plan 2018 - 2023 Illustrations i Illustrations Figures Fig. 1 Location Map Fig. 2 Archaeological Constraint Map, www.archaeology.ie Fig. 3 Drumanagh and Lambay promontory forts (Westropp, 1921) Fig. 4 Knock Dhu overall site plan, showing know hut circles (MacDonald 2016, 3) Fig. 5 Down Survey Barony Map c.1656 Fig. 6 Down Survey Parish Map c.1656 Fig. 7 Rocque’s Map of county Dublin, 1760 Fig. 8 Duncan’s 1821 map Fig. 9 First Edition Ordnance Survey Map... Surveyed 1838, Published 1843 Fig. 10 Drawing 14 C 15(28) (1) Courtesy of the Royal Irish Academy © Fig. 11 25 inch Ordnance Survey Map. Surveyed 1906; Published 1908 Fig. 12 Area 1A Interpretative Plan. Courtesy of the Discovery Programme Fig. -

Castle Structure and Function

Vocabulary Castle Structure and Function Name: Date: Castle Use A Castle’s Structure: · Large and of great defensive strength · Surrounded by a wall with a fighting platform · Usually has a large, strong tower A Castle’s Function: · Fortress and military protection · Center of local government · Home of the owner, usually a king The Parts of a Castle allure: the walkway at the top of a castle wall. The allure was often shielded by a protective wall so that guards could move between towers; also called a wall-walk arcading: a series of columns and arches, built in an upside-down U shape arrow loop: a tiny vertical opening in the castle wall; a thin window used for shooting arrows at the enemy; also called a loophole or meurtriere ashlar: blocks of stone, used to build castle wa lls and towers bailey: an open, grassy area inside the walls of the castle containing farm pastures, cottages, and other buildings. Sometimes a castle had more than one bailey; also called a ward. balustrade: railing along a path or stairway barrel vault: semicircular roof made out of wood or stone bastion: a small tower on a courtyard wall or an outside wall battlement: a narrow wall built along the outer edge of the wall-walk to protect soldiers against attack boss: the middle stone in an arch; also called a keystone concentric: having two sets of walls, one inside the other cornerstone: a stone at the corner of a building uniting two intersecting walls, sometimes inscribed with the year the building was constructed; also called a quoin crosswall: a wall inside a large tower Lesson Connection: Castles and Cornerstones Copyright The Kennedy Center. -

Storms and Coastal Defences at Chiswell This Booklet Provides Information About

storms and coastal defences at chiswell this booklet provides information about: • How Chesil Beach and the Fleet Lagoon formed and how it has What is this changed over the last 100 years • Why coastal defences were built at Chiswell and how they work • The causes and impacts of the worst storms in a generation booklet that occurred over the winter 2013 / 14 • What will happen in the future Chesil Beach has considerable scientific about? significance and has been widely studied. The sheer size of the beach and the varying size and shape of the beach material are just some of the reasons why this beach is of worldwide interest and importance. Chesil Beach is an 18 mile long shingle bank that stretches north-west from Portland to West Bay. It is mostly made up of chert and flint pebbles that vary in size along the beach with the larger, smoother pebbles towards the Portland end. The range of shapes and sizes is thought to be a result of the natural sorting process of the sea. The southern part of the beach towards Portland shelves steeply into the sea and continues below sea level, only levelling off at 18m depth. It is slightly shallower at the western end where it levels off at a depth of 11m. This is mirrored above sea level where typically the shingle ridge is 13m high at Portland and 4m high at West Bay. For 8 miles Chesil Beach is separated from the land by the Fleet lagoon - a shallow stretch of water up to 5m deep. -

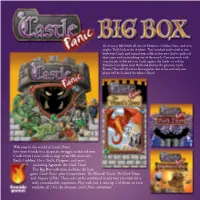

RULES for the Castle Panic Big

The forest is filled with all sorts of Monsters. Goblins, Orcs, and even mighty Trolls lurk in the shadows. They watched and waited as you built your Castle and trained your soldiers, but now they’ve gathered their army and are marching out of the woods. Can you work with your friends to defend your Castle against the horde, or will the Monsters tear down your Walls and destroy the precious Castle Towers? You will all win or lose together, but in the end only one player will be declared the Master Slayer! Welcome to the world of Castle Panic! Join your friends in a desperate struggle to defend your Castle from a near-endless siege of terrible monsters. Battle Goblins, Orcs, Trolls, Dragons, and more, including Agranok, the Dark Titan! This Big Box collection includes the base game Castle Panic, plus 3 expansions: The Wizard’s Tower, The Dark Titan, and Engines of War. These sets can be combined in any way you wish for a truly customizable experience. Play with just 1, mix up 2 of them, or even combine all 3 for the ultimate Castle Panic adventure! OBJECTIVE COMPONENTS • 6 Towers with plastic stands: Towers are the heart of the Castle Panic is a cooperative game in which All of the components are described in detail Castle. If the Monsters destroy the players work together rather than on pp. 8–11. all of the Towers, the players compete. Players use cards to hit and slay lose the game. Monsters as the Monsters advance from • 1 Board the Forest toward the Castle. -

Hans Christian Andersen Museum

Signature Route Royal Denmark & Living History Signature Route A kingdom for more than 1000 years, Denmark offers a wealth of royal attractions, from castles and palaces in heritage settings to magnificent gardens. Denmark also offers a chance to stay and dine like a prince or princess at castles and in romantic villages in the nation's scenic countryside. Signature Route – Royal Denmark & Living History Copenhagen Helsingør Roskilde Odense Jelling Ribe Møn Sealand Copenhagen Amalienborg Palace The official residence of the Queen of Denmark. Here you can visit the royal chambers of the Amalienborg Museum and see the changing of the royal guards at noon. One of Europe’s finest examples of a Rococo palace, Amalienborg consists of four mansions and an octangular square. When the royal ensign flies from the mast, the Queen is home. Rosenborg Castle A 300-year-old castle in a leafy parkland in downtown Copenhagen. The shoebox-sized castle was once a royal summer residence. Today, it showcases heritage collections as well as the Danish Crown Jewels. The King’s Garden next to the castle is a peaceful oasis where you will find a statue of storyteller Hans Christian Andersen. Tivoli Gardens One of the world’s oldest and most magical amusement parks with flower gardens, rides and restaurants. The gardens are open during four annual seasons – Summer, Halloween, Christmas and Winter. Each season is unique. Tivoli Gardens is located in the heart of the city. Visit Carlsberg The original site of the Carlsberg Breweries is today home to a visitor’s centre where you can learn about the art of brewing beer.