Download This Article As a PDF (425

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Engine Riding Positions Officer Heo Nozzle Ff

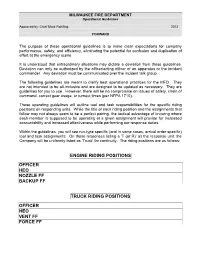

MILWAUKEE FIRE DEPARTMENT Operational Guidelines Approved by: Chief Mark Rohlfing 2012 FORWARD The purpose of these operational guidelines is to make clear expectations for company performance, safety, and efficiency, eliminating the potential for confusion and duplication of effort at the emergency scene. It is understood that extraordinary situations may dictate a deviation from these guidelines. Deviation can only be authorized by the officer/acting officer of an apparatus or the incident commander. Any deviation must be communicated over the incident talk group. The following guidelines are meant to clarify best operational practices for the MFD. They are not intended to be all-inclusive and are designed to be updated as necessary. They are guidelines for you to use. However, there will be no compromise on issues of safety, chain of command, correct gear usage, or turnout times (per NFPA 1710). These operating guidelines will outline tool and task responsibilities for the specific riding positions on responding units. While the title of each riding position and the assignments that follow may not always seem to be a perfect pairing, the tactical advantage of knowing where each member is supposed to be operating at a given assignment will provide for increased accountability and increased effectiveness while performing our response duties. Within the guidelines, you will see run-type specific (and in some cases, arrival order specific) tool and task assignments. On those responses listing a ‘T (or R)’ as the response unit, the Company will be uniformly listed as ‘Truck’ for continuity. The riding positions are as follows: ENGINE RIDING POSITIONS OFFICER HEO NOZZLE FF BACKUP FF TRUCK RIDING POSITIONS OFFICER HEO VENT FF FORCE FF SAFETY If you see something that you believe impacts our safety, it is your duty to report it to your superior Officer immediately. -

The Art of the Breach

The Art of the Breach A journey from sidewalk to executive filing cabinet highlighting three different approaches to achieve our objective. Passive entry: Social engineering Covert entry: Lockpicking Forced entry: What ever it takes 1 The Art of the Breach Founder: Nonprofit Crowdsourced OSINT for Missing Persons www.tracelabs.org Profession: Senior IT Manager, Aerospace Industry www.linkedin.com/in/robertsell Volunteer: Coquitlam Search & Rescue: Tracker www.coquitlam-sar.bc.ca Twitter:@robertesell Email: [email protected] 2 The Art of the Breach Housekeeping: • Standard disclaimer: None of this material or ideas in no way represent employers or even potential employers from past, present or future. • Risk of Incarceration: Physically breaking into a building without authorization from the owner is strictly forbidden. It is physically dangerous, costly and depending on your local laws, almost certainly criminal. This content is being provided so that you may have a better understanding of criminal breach methodologies, allowing your organization to better prepare to defend against it. 3 The Art of the Breach 1 Research Target 2 Prepare Pretexts 7 3 Onsite Reconnaissance 6 4 Front/Back Door 5 Lobby 6 Elevator/Stairs/Hallway 5 7 Executive Office 4 8 Escape and Evade 3 4 The Art of the Breach 1 Research Target Passive reconnaissance / Zero touch recon: • Start at a high level and drill down into details • Prepare before you start: • VM for dedicated and archivable platform • Sock puppets or correct settings • VPN (not just for privacy -

Wildlife Water Catchment Construction in Nevada

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. Bureau of Land Management Papers U.S. Department of the Interior 2003 Wildlife Water Catchment Construction in Nevada William R. Brigham Bureau of Land Management Craig Stevenson Nevada Division of Wildlife Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usblmpub Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Brigham, William R. and Stevenson, Craig, "Wildlife Water Catchment Construction in Nevada" (2003). U.S. Bureau of Land Management Papers. 25. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usblmpub/25 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of the Interior at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in U.S. Bureau of Land Management Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Cover photo of Desert Bighorn ewe and lamb at the Butte Guzzler east of Mina, Nevada, by Andy Stinson of Hawthorne, Nevada. Chapter Two and Appendix A photos by William R. “Rick” Brigham, BLM Carson City District, Nevada. Production services provided by: Publishing Staff Peter Doran (303-236-6547) Janine Koselak: Layout and Design Kathy Rohling: Editing Lee Barkow, Director National Science & Technology Center P.O. Box 25047 Denver, Colorado 80225-0047 The Bureau of Land Management’s National Science and Technology Center supports other BLM offices by providing a broad spectrum of services in areas such as physical, biological, and social science assessments; architecture and engineering support; library assistance; mapping science; photo imaging; geographic information systems applications; and publications support. COPIES AVAILABLE FROM: BLM National Business Center Printed Materials Distribution Service, BC-652 P.O. -

Green Bay Fire Department Edgewood Analysis Team Incident

Green Bay Fire Department Edgewood Analysis Team Incident #5747 Final Report Lieutenant Arnie Wolff July 14, 1951 - August 13, 2006 Page i In Memoriam Lieutenant Arnie Wolff July 14, 1951 – August 13, 2006 “WE WILL NEVER FORGET” Your Brothers and Sisters of the Green Bay Fire Department Page ii PREFACE Tragically, on August 13 th 2006, Green Bay Fire Department Lieutenant Arnie Wolff lost his life in the line of duty. The Wolff family and the Green Bay Fire Department family suffered a tremendous loss on this day. This report is dedicated to ‘Arnie’, his wife, his children, …and to his firefighting family. Arnie’s many contributions as a firefighter/paramedic, soccer coach, and friend will never be forgotten. His calm demeanor, caring dedication to his profession and to his co-workers and the citizens he served, has forever enriched those who knew Arnie personally. Following the collapse on Edgewood Drive, fire department personnel on the scene performed at extraordinary levels. There were numerous displays of heroism demonstrated by members of the department during the rescue of firefighter Jo Brinkley-Chaudoir and repeated attempts to reach Lt. Wolff. We present this report and the recommendations that come from it to the Fire Chief, the Mayor and Common Council, and the members of the Green Bay Fire Department for their consideration. We have come together with a unity of purpose because August 13 th, 2006 was a day of deep shock and suffering for us. How could this have happened? How can we avoid such a tragedy from ever happening again? The Edgewood Analysis Team was convened to answer these questions. -

![Firefighter Rookie Book ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2572/firefighter-rookie-book-2292572.webp)

Firefighter Rookie Book ]

[ HVFD – Firefighter Rookie Book ] Firefighter Rookie Book WHAT’S INSIDE 3 Introduction 29 Truck Company Operating Areas 4 Radio Procedures 31 Truck Company Non-Mask Probationary Firefighter Check-Off 7 Engine Company Operations 33 Truck Company Mask 9 Engine Riding Position Probationary Firefighter Check-Off 13 Engine Layout 35 Rescue Company Operations 11 Engine Company Equipment 37 Rescue Squad 1 Tool Inventory List 15 Engine Equipment Study Guide 46 20 Fair Assumptions about 19 Engine Company Non-Mask Garden Apartment Fires Probationary Firefighter Check-Off 48 Firefighter Motivation 21 Engine Company Mask 50 Types Of Contruction Probationary Firefighter Check-Off 51 Non-Mask Qualification Sheet 23 Engine Company Key Points 57 Mask Qualification Sheet 25 Truck Company Operations Updated 1/15/2017 Introduction The Firefighter Rookie Book is intended as a guide for Fire/EMS members through the turnover process from joining the department through being a fully qualified firefighter. The Firefighter Rookie Book should be used in conjunction with the following documents comprising the HVFD Handbook: 1. The HVFD Member Guide which outlines the initial steps after completing Volunteer Recruit School (or transferring in) required to begin the formal turnover processes and check sheets outlined here, key training requirements, scheduling, progression information, training sign up details and more. 2. The EMS Rookie Book, outlining the turnover process for our EMS units from VRS through Charge EMT. 3. Prince George’s County Fire/EMS Department General Orders. Dispatch and on scene incident procedures are dictated by these General Orders. Copies of key General Orders related to EMS operations are included in the HVFD Handbook and all operational members must read through them thoroughly. -

Fireterminology.Pdf

Abandonment: Abandonment occurs when an emergency responder begins treatment of a patient and the leaves the patient or discontinues treatment prior to arrival of an equally or higher trained responder. Abrasion: A scrape or brush of the skin usually making it reddish in color and resulting in minor capillary bleeding. Absolute Pressure: The measurement of pressure, including atmospheric pressure. Measured in pound per square inch absolute. Absorption: A defensive method of controlling a spill by applying a material that absorbs the spilled material. Accelerant: Flammable fuel (often liquid) used by some arsonists to increase size or intensity of fire. Accelerator: A device to speed the operation of the dry sprinkler valve by detecting the decrease in air pressure resulting in acceleration of water flow to sprinkler heads. Accountability: The process of emergency responders (fire, police, emergency medical, etc...) checking in as being on-scene during an incident to an incident commander or accountability officer. Through the accountability system, each person is tracked throughout the incident until released from the scene by the incident commander or accountability officer. This is becoming a standard in the emergency services arena primarily for the safety of emergency personnel. Adapter: A device that adapts or changes one type of hose thread, type or size to another. It allows for connection of hoses and pipes of incompatible diameter, thread, or gender. May contain combinations, such as a double-female reducer. Adapters between multiple hoses are called wye, Siamese, or distributor. Administrative Warrant: An order issued by a magistrate that grants authority for fire personnel to enter private property for the purpose of conducting a fire prevention inspection or similar purpose. -

The Hyattsville Volunteer Fire Department

The Hyattsville Volunteer Fire Department Company Rookie Manual Last Revision Summer 2013 Edited by Matthew Leonard Contribution from Summer 2009 Rookie Book & Spring 2013 Live-ins Introduction Welcome to the Hyattsville Volunteer Fire Department. Whether you are new to the fire service or have been with other companies in the past the HVFD is a unique fire company in a unique fire department. The HVFD has a strong sense of pride and tradition that dates back to 1888 with a sincere dedication to serig the itizes of the Cit of Hattsille ad Prie George’s County, Maryland. One thing you will be doing regardless of the prior experience you have is serving as a volunteer in a busy metropolitan fire department. Our fire company responds annually to thousands of emergencies including medical emergencies, vehicle accidents, technical rescues, structural fires, and general calls for assistae to the people e sere. The HVFD is oe of ol to opaies i Prie George’s County that operates all 3 primary suppression and rescue services as well as a BLS ambulance. Because of the diversity of our tasks the HVFD must maintain a high level of discipline and a high level of competence in its members. This book is designed to assist you with becoming a well-trained and knowledgeable volunteer and will help you attain any goals you wish to achieve whether it is in fire or EMS. There is a basic level study material as well as benchmarks within these pages and exams to help you gauge you proficiency and obtain various statuses as you move through your probation and rookie hood. -

1. Call to Order 2. Invocation 3. Pledge of Allegiance 4

MEETING OF THE MAYOR AND BOARD OF ALDERMEN SOUTHAVEN, MISSISSIPPI CITY HALL June 15, 2021 6:00 PM AGENDA 1. Call To Order 2. Invocation 3. Pledge Of Allegiance 4. Approval of Minutes: June 1, 2021 5. Resolution for Free Port Warehouse Tax Exemption for Helen of Troy, LP 6. Authorization to Apply for RAISE Grant Funds 7. DCCVB MOU 8. Authorization for Fire Pumper (Truck) Proposal 9. Contract with Neel-Schaffer for Stormwater Management 10. Authorization to Bid Construction of the Starlanding Road Water Treatment Plant 11. Resolution to Clean Private Property 12. Planning Agenda: Item #1 Application by Pinnacle Development to rezone 5 acres of property on the east side of Swinnea Road, north of Greencliff from R-10 to PUD 13. Mayor’s Report 14. Personnel Docket 15. City Attorney’s Legal Update 16. Utility Bill Adjustment Docket 17. Claims Dockets: Docket 1 Docket 2 Docket 3 18. Executive Session: Claims/Litigation Against the SPD; Citywide Personnel; Economic Development Items may be added to or omitted from this agenda as needed. RESOLUTION OF THE MAYOR AND BOARD OF ALDERMEN OF THE CITY OF SOUTHAVEN, MISSISSIPPI, GRANTING FREE PORT WAREHOUSE AD VALOREM TAX EXEMPTION TO HELEN OF TROY, LP AS AUTHORIZED BY SECTION 27-31-51 ET. SEQ., OF THE MISSISSIPPI CODE (1972), AS AMENDED WHEREAS, Helen of Troy, LP (“Helen”) seeks an exemption from ad valorem taxes at its warehouse operation located at 8474 Marketplace Drive, Southaven, Mississippi to the fullest extent permitted by statute on all personal property held in the applicant’s finished good -

NKCTC Firefighter Fundamentals Manual

NKCTC Firefighter Fundamentals SEPTEMBER 2020 North King County Training Consortium TABLE OF CONTENTS (Click on any title to jump to that SECTION) SECTION SECTION TITLE 1 Hand Tools 2 Rope 3 Power Equipment 4 Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) 5 Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus (SCBA) 6 Forcible Entry 7 Search & Rescue 8 Firefighter Survivability 9 Ladders 10 Ventilation 11 Hose & Appliances Click the button to return to this page HAND TOOLS Alan wrench set/Hex key/ Allen key: because the flat head can be used as a striking tool. Long arching swings should not be used with axes. This method increases the danger of hitting other members or overhead obstructions. When using a A tool with a hexagonal cross-section used wooden handled axe, due to the grain of to drive bolts and screws that have a the wood, the strongest axis when using the hexagonal socket in the head (internal axe to pry is in line with the head or pick of wrenching hexagon drive). They may be the axe. Care must be used when prying in either American or Metric sizes. the direction of either side of the head of the axe. AXES Pry Axe: Pick Head Axe: The pry axe has features not normally found Comes with a 28-36” handle with a 6-8 lb. on traditional rescue tools. The head of the axe head on one side and a pick head on tool has a shortened pick head axe with the other. This is an excellent prying tool serrated teeth on the underside of the axe when the pick end is engaged. -

Research Roadmap for Smart Fire Fighting Summary Report

NIST Special Publication 1191 | NIST Special Publication 1191 Research Roadmap for Smart Fire Fighting Research Roadmap for Smart Fire Fighting Summary Report Summary Report SFF15 Cover.indd 1 6/2/15 2:18 PM NIST Special Publication 1191 i Research Roadmap for Smart Fire Fighting Summary Report Casey Grant Fire Protection Research Foundation Anthony Hamins Nelson Bryner Albert Jones Galen Koepke National Institute of Standards and Technology http://dx.doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.1191 MAY 2015 This publication is available free of charge from http://dx.doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.1191 U.S. Department of Commerce Penny Pritzker, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology Willie May, Under Secretary of Commerce for Standards and Technology and Director SFF15_CH00_FM_i_xxii.indd 1 6/1/15 8:59 AM Certain commercial entities, equipment, or materials may be identified in this document in order to describe an experimental procedure or concept adequately. Such identification is not intended to imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, nor is it intended to imply that the entities, materials, or equipment are necessarily the best available for the purpose. The content of this report represents the contributions of the chapter authors, and does not necessarily represent the opinion of NIST or the Fire Protection Research Foundation. National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 1191 Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 1191, 246 pages (MAY 2015) This publication is available -

058 Smokejumper Issue 058 J

The National Smokejumper Quarterly Magazine SmokejumperAssociation January 2008 Ever Have a Fire with Jerry Daniels?.................................................5 A Tribute to Pilot Jim Larkin .........................................................12 A Critique of Rescue Dawn ............................................................23 CONTENTS Message from Message from the President ......................... 2 Idaho Needs to Welcome the Morgans Home 3 the President Elections for NSA ......................................... 3 Were You Ever on a Fire with Jerry Daniels? 5 Odds and Ends ............................................. 6 of our soul. We are jumpers, active or not. The reality is that the next jump by Fire Information .......................................... 8 any one of these young jumpers could Jumper Ingenuity in Alaska, 1961 ................ 9 bring them into their definition of the Spotting ..................................................... 10 ranks of the NSA. A Tribute to Jim Larkin-Forest Service Pilot 12 I was very fortunate not being in- A “Friends-Helping-Friends” Request ........ 14 jured thru 535 jumps, often feeling New NSA Life Members Since January 2007 14 bulletproof just like a lot of the young The View from Outside the Fence ............... 15 jumpers. However, that could have Jumping the Steens .................................... 16 been altered at any jump. So, those Ted Dethlefs Collection Centerfold ............ 18 that think the NSA is just for those John E. “Jack” Nash-Another Pioneer Jumper outside the ranks of the active, please 20 rethink that concept and accept the Russian Smokejumper Ivan Alexandrovich by Doug Houston fact that we all are one, bonded by the Novik ................................................... 21 (Redmond ’73) smokejumping experiences of the past, If It Could Go Wrong, It Did! ...................... 22 PRESIDENT present, and the future. It’s all good. A Critique of the Movie Rescue Dawn ........ -

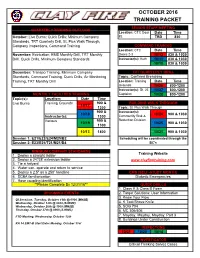

October 2016 Training Packet

OCTOBER 2016 TRAINING PACKET SENIOR STAFF MEETING QUARTERLY TRAINING OUTLOOK Location: CTC Door Date Time October: Live Burns; Quick Drills; Minimum Company #2 TBD 830 Standards, TRT Quarterly Drill, St. Pius Walk Through, Company Inspections, Command Training COMMAND TRAINING Location: CTC Date Time November: Extrication; EMS Monthly Drill, TRT Monthly Doors 2-3 10/13 830 & 1030 Drill, Quick Drills, Minimum Company Standards Instructor(s): Huth 10/11 830 & 1030 10/10 830 & 1030 December: Transpo Training, Minimum Company TRT QUARTERLY DRILL Standards, Command Training, Quick Drills, Air Monitoring Topic: Confined Breaching Training, TRT Monthly Drill Location: Training Date Time Grounds 10/26 800-1200 Instructor(s): St. 23 10/27 800-1200 MONTHLY FACILITIES TRAINING Captains 10/28 800-1200 Topic(s): Location: Date Time Live Burns Training Grounds 900 & BUILDING WALK THROUGH 10/17 1300 Topic: St. Pius Walk Through 900 & Instructor(s): 10/18 10/24 900 & 1030 Instructor(s): 1300 Community Risk & Various 900 & Reduction Division 10/19 10/25 900 & 1030 1300 10/13 1800 10/21 900 & 1030 Session 1: E21/E22/E24/M25/B2 Scheduling will be coordinated through the Session 2: E23/E25/T21/M21/B4 BC's MINIMUM COMPANY STANDARDS Training Website 1. Deploy a straight ladder 2. Deploy a 24'/28' extension ladder www.clayfiretraining.com 3. Tie a halyard 4. Water can- operate and return to service 5. Deploy a 2.5" as a 250' handline EMS (SELF-STUDY MONTH) 6. SCBA familiarization Diabetic Emergencies 7. Hose coupling identification **Please Complete By 12/31/16** QUICK DRILLS 1. Class A & Class B Foam UPCOMING EVENTS 2.