“I'm a Survivor!”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewish Self-Hatred and the Larry Sanders Show

“Y’ALL KILLED HIM, WE DIDN’T” Jewish Self-Hatred and The Larry Sanders Show Vincent Brook University of Southern California Did the Jews invent self-hatred? A case can be made—from the production and the reception end. Centuries before they were branded collective Christ killers in the Gospel of St. Matthew, a calumny that laid the groundwork for both anti-Semitism and Jewish self-hatred, Jews themselves had planted the seeds of self-hatred for all humanity in the Garden of Eden. The biblical God’s banishment of the ur-couple from Paradise inflicted a primordial self-loathing that would prove, at least for the faithful, all but inexpungable. Then there’s the Jewish Freud, whose non-denominational take on Original Sin postulated a phylogenic and an ontogenic source: the collective killing of the Primal Father and the individual Oedipal complex. Freud’s daughter Anna, meanwhile, gave self-hatred back to the Jews through her concept of “identification with the aggressor,” which, while applicable universally, derived specifically from the observations of Jewish children who had survived Hitler Germany and yet identified positively with their Nazi persecutors and negatively with themselves as Jewish victims. Last not least, the poet laureate of existential angst, Franz Kafka, historicized self- hatred, laying the theoretical and experiential groundwork for what Jewish filmmaker Henry Bean calls “the ambivalent, self-doubting, self-hating modern condition.”1 To ascribe a privileged role for Jews in the encoding and decoding of self-hatred is certainly not to deny other groups’ significant enmeshment in the process. Just as Jews have introjected anti-Semitism, people of color, women, gays, and lesbians have internalized the damaging social messages of racism, misogyny, and homophobia, directing against themselves the projected hatred of the normative society. -

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

BEN-GURION UNIVERSITY OF THE NEGEV THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN LITERATURES AND LINGUISTICS THE REPRESENTATION OF JEWISH MASCULINITY IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN SITCOMS THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS SHANY ROZENBLATT 021692256 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF: PROF. EFRAIM SICHER November 2014 BEN-GURION UNIVERSITY OF THE NEGEV THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN LITERATURES AND LINGUISTICS THE REPRESENTAION OF JEWISH MASCULINITY IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN SITCOMS THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS SHANY ROZENBLATT 021692256 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF: PROF. EFRAIM SICHER Signature of student: ________________ Date: _________ Signature of supervisor: ________________ Date: _________ Signature of chairperson of the committee for graduate studies: _______________ Date: _________ November 2014 Abstract This thesis explores the representation of Jewish characters in contemporary American television comedies in order to determine whether Jews are still depicted stereotypically as emasculate. The thesis compares Jewish and non-Jewish masculinities in American Television sitcom characters in shows airing from the 1990's to the present: Seinfeld, Friends, and The Big Bang Theory. The thesis asks whether there is a difference between the representation of Jews and non-Jews in sitcoms, a genre where most men are mocked for problematic masculinity. The main goal of the thesis is to find out whether old stereotypes regarding Jewish masculinity – the "jew" as weak, diseased, perverted and effeminate – still exist, and how the depiction of Jewish characters relates to the Jews' assimilation and acceptance in America. -

An Alternative Comedy History – Interrogating Transnational Aspects of Humour in British and Hungarian Comedies of the Inter-War Years

An Alternative Comedy History – Interrogating Transnational Aspects of Humour in British and Hungarian Comedies of the Inter-War Years Anna Martonfi Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of East Anglia School of Art, Media and American Studies Submitted May 2017 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Abstract Anna Martonfi, University of East Anglia, 2017 Supervisors: Dr Brett Mills and Dr Melanie Williams This thesis is a historical research into British comedy traditions made during an era when numerous creative personnel of Jewish backgrounds emigrated from Central and Eastern European countries to Britain. The objective is to offer an alternative reading to British comedy being deeply rooted in music hall traditions, and to find what impact Eastern European Jewish theatrical comedy traditions, specifically urban Hungarian Jewish theatrical comedy tradition ‘pesti kabaré’, may have had on British comedy. A comparative analysis is conducted on Hungarian and British comedies made during the inter-war era, using the framework of a multi-auteurist approach based on meme theory and utilising certain analytical tools borrowed from genre theory. The two British films chosen for analysis are The Ghost Goes West (1935), and Trouble Brewing (1939), whereas the two Hungarian films are Hyppolit, the Butler (1931), and Skirts and Trousers (1943). The purpose of this research within the devised framework is to point out the relevant memes that might refer to the cultural transferability of Jewish theatrical comedy traditions in the body of films that undergo analysis. -

Myers, Allison.Pdf

FROM ALEICHEM TO ALLEN: THE JEWISH COMEDIAN IN POPULAR CULTURE by Allison Myers A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in English with Distinction. Spring 2010 Copyright 2010 Allison Myers All Rights Reserved FROM ALEICHEM TO ALLEN: THE JEWISH COMEDIAN IN POPULAR CULTURE by Allison Myers Approved: ______________________________________________________________________________________ Elaine Safer, Ph.D. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: ______________________________________________________________________________________ Ben Yagoda, M.A. Committee member from the Department of English Approved: ______________________________________________________________________________________ John Montaño, Ph.D. Committee member from the Board of Senior Thesis Readers Approved: ______________________________________________________________________________________ Ismat Shah, Ph.D. Chair of the University Committee on Student and Faculty Honors ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express utmost gratitude to my thesis advisor, Elaine Safer, for all the guidance she has given and for all the jokes she has told me over the course of writing my thesis. I also extend my thanks to Ben Yagoda and John Montaño, my thesis committee, for guiding me in this process. It is because of University of Delaware’s incredible Undergraduate Research Program that I was able to pursue my interests and turn it into a body of work, so I owe the department, and specifically Meg Meiman, many thanks. Finally, I am grateful for every fellow researcher, family member and friend who has lent me a book, suggested a comedian, or just listened to me ramble on about the value of studying Jewish humor. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................................................................................................................. -

The Schlemiel and the Schlimazl in Seinfeld

Journal of Popular Film and Television ISSN: 0195-6051 (Print) 1930-6458 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjpf20 The Schlemiel and the Schlimazl in Seinfeld Carla Johnson To cite this article: Carla Johnson (1994) The Schlemiel and the Schlimazl in Seinfeld, Journal of Popular Film and Television, 22:3, 116-124, DOI: 10.1080/01956051.1994.9943676 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/01956051.1994.9943676 Published online: 14 Jul 2010. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 44 Citing articles: 7 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjpf20 ~~ ~ ~~ ~~ ~ Over five seasons, America has witnessed the schlemiel-and-schlimazlstyle idiocies of sidekicks Elaine, Jerry Seinfeld, and George. 116 The Schlemiel and the Schlimazl in Seinfeld By CARLA JOHNSON omeone has stolen George’s whose ‘accident’ spills the soup ... onto glasses, or so he thinks. He others” (Pinkster 6). In the above has actually left them on top episode (aired 2 December 1993), Jerry of his locker at the health plays the schlimazl to George’s club. He steps out from the optical schlemiel. Over five seasons, in episode shop, where he is trying on new after well-watched episode, America frames, squints down the street, and has witnessed the schlemiel-and- “sees” Jerry’s girlfriend Amy kissing schlimazl style idiocies of sidekicks Jerry’s cousin. Never mind that the Jerry, George, and Elaine.2 Whereas frames he is wearing have no lenses. George Costanza, Elaine Benes, and He reports the siting to Jerry. -

Fahie Sarah MA CWE Spring2

handwringers A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Creative Writing and English University of Regina by Sarah Fahie Regina, Saskatchewan December 2019 Copyright 2019: S. Fahie UNIVERSITY OF REGINA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES AND RESEARCH SUPERVISORY AND EXAMINING COMMITTEE Sarah Dawn Fahie, candidate for the degree of Master of English in Creative Writing and English, has presented a thesis titled, handwringers, in an oral examination held on December 12, 2019. The following committee members have found the thesis acceptable in form and content, and that the candidate demonstrated satisfactory knowledge of the subject material. External Examiner: Dr. Steven Ellerhoff, Southwestern Oregan Community College Supervisor: Dr. Michael Trussler, Department of English Committee Member: Dr. Marcel DeCoste, Department of English Committee Member: Dr. Jes Battis, Department of English Chair of Defense: Dr. Philip Charrier, Department of History *via Video Conference Abstract Lying on his couch, reflecting on his life, Moses E. Herzog “thought awhile of Mithridates, whose system learned to thrive on poison. He cheated his assassins, who made the mistake of using small doses, and was pickled, not destroyed. Tutto fa brodo” (Bellow 4). Saul Bellow’s titular character offers an excellent metaphor for a complicated figure: the schlemiel. Herzog reflects on Mithridate’s inability to die with honor: having fortified himself against poisoning, he botches his suicide. The Italian phrase Bellow uses to describe Herzog’s state of mind is an idiom meaning literally “everything makes broth” suggesting that every little bit helps. -

Contentious Comedy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenGrey Repository 1 Contentious Comedy: Negotiating Issues of Form, Content, and Representation in American Sitcoms of the Post-Network Era Thesis by Lisa E. Williamson Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Glasgow Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies 2008 (Submitted May 2008) © Lisa E. Williamson 2008 2 Abstract Contentious Comedy: Negotiating Issues of Form, Content, and Representation in American Sitcoms of the Post-Network Era This thesis explores the way in which the institutional changes that have occurred within the post-network era of American television have impacted on the situation comedy in terms of form, content, and representation. This thesis argues that as one of television’s most durable genres, the sitcom must be understood as a dynamic form that develops over time in response to changing social, cultural, and institutional circumstances. By providing detailed case studies of the sitcom output of competing broadcast, pay-cable, and niche networks, this research provides an examination of the form that takes into account both the historical context in which it is situated as well as the processes and practices that are unique to television. In addition to drawing on existing academic theory, the primary sources utilised within this thesis include journalistic articles, interviews, and critical reviews, as well as supplementary materials such as DVD commentaries and programme websites. This is presented in conjunction with a comprehensive analysis of the textual features of a number of individual programmes. By providing an examination of the various production and scheduling strategies that have been implemented within the post-network era, this research considers how differentiation has become key within the multichannel marketplace. -

The Culture of Post-Narcissism

THE CULTURE OF POST-NARCISSISM The Culture of Post-Narcissism Post-teenage, Pre-midlife Singles Culture in Seinfeld, Friends, and Ally – Seinfeld in Particular MICHAEL SKOVMAND In a recent article, David P. Pierson makes a persuasive case for considering American television comedy, and sitcoms in particular, as ‘Modern Comedies of Manners’. These comedies afford a particular point of entry into contemporary mediatised negotiations of ‘civility’, i.e. how individual desires and values interface with the conventions and stand- ards of families, peer groups and society at large. The apparent triviality of subject matter and the hermetic appearance of the groups depicted may deceive the unsuspecting me- dia researcher into believing that these comedies are indeed “shows about nothing”. The following is an attempt to point to a particular range of contemporary American televi- sion comedies as sites of ongoing negotiations of behavioural anxieties within post-teen- age, pre-midlife singles culture – a culture which in many aspects seems to articulate central concerns of society as a whole. This range of comedies can also be seen, in a variety of ways, to point to new ways in which contemporary television comedy articu- lates audience relations and relations to contemporary culture as a whole. American television series embody the time-honoured American continental dicho- tomy between the West Coast and the East Coast. The West Coast – LA – signifies the Barbie dolls of Baywatch, and the overgrown high school kids of Beverly Hills 90210. On the East Coast – more specifically New York and Boston, a sophisticated tradition of television comedy has developed since the early 1980s far removed from the beach boys and girls of California. -

Oshkosh Scholar Submission – Volume VI – 2011

Oshkosh Scholar Submission – Volume VI – 2011 How Nothing Became Something: The Evolution of Seinfeld Eric Balkman, author Justine Stokes, Radio-TV-Film, faculty adviser Eric Balkman will graduate in December 2011 with a double major in journalism and radio-TV- film. His research on Seinfeld began when he was a sophomore at UW-Fox Valley as a term paper for a philosophy of the arts class. This article was his final project for Justine Stokes’ television genre and aesthetics class. Justine Stokes is the director of television services for UW Oshkosh. She earned her M.A. in mass communication at Miami University (Ohio) and her B.A. in mass communication and theatre from Morningside College (Iowa). Stokes directed and produced “Affinity,” which won an honorable mention at the 2007 Wonder Women Film Competition in New York City. “Affinity” also won AfterElton.com’s Inaugural Short Film Competition. Stokes has directed and produced a wide variety of local television as well. Abstract This thesis argues that no one factor by itself contributed to the explosion of Seinfeld into pop culture, and no single cause has ultimately placed it in the pantheon of the greatest situation comedies in television history. Through extensive research and exhaustive viewing, three of the minor factors that led Seinfeld to prominence were ultimately being the beneficiary of riding the proverbial coattails of Cheers to build a following, being a fledgling show on a foundering network that decided to take a chance on it in order to spurn its demise and not being written to appeal to a mass audience. -

Popular Representations of Jewish Identity on Primetime Television: the Ac Se of the .OC

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Media and Cultural Studies Honors Projects Media and Cultural Studies 5-1-2006 Popular Representations of Jewish Identity on Primetime Television: The aC se of The .OC. Tamara Olson Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/hmcs_honors Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons Recommended Citation Olson, Tamara, "Popular Representations of Jewish Identity on Primetime Television: The asC e of The .OC." (2006). Media and Cultural Studies Honors Projects. Paper 1. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/hmcs_honors/1 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Media and Cultural Studies at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Media and Cultural Studies Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Popular Representations of Jewish Identity on Primetime Television: The Case of The O.C. Tamara Jill Olson Senior Honors Thesis Department: Humanities and Media and Cultural Studies Advisor: Leola Johnson Readers: Vincent Doyle and J. Andrew Overman Date Submitted: May 1, 2006 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Chapter 1: A History of Jewish Identity and Representations in Mass Media 13 Chapter 2: Jews on Television 42 Chapter 3: Methods: Reading The O.C. as a Cultural Text 60 Chapter 4: Television and the Construction of a White, Post-Jewish Identity: A Close Reading of The O.C. 69 Conclusion: Exploring the Postmodern, Secular Jewish Identity as a Brand of Whiteness 104 Works Cited 109 2 Introduction The O.C. -

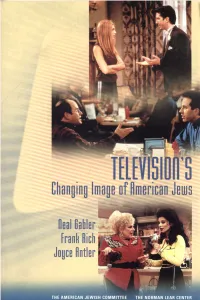

Changing Image of American Jems

Changing Image of American Jems Heal Gabler Frank Rich Joyce Untier THE AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE THE NORMAN LEAR CENTER THE AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE protects the rights and freedoms of Jews the world over; combats bigotry and anti-Semitism and promotes human rights for all; works for the security of Israel and deepened understanding between Americans and Israelis; advocates public policy positions rooted In American democratic values and the perspective of the Jewish heritage; and enhances the creative vitality of the Jewish people. Founded in 1906, it is the pioneer human-relations agency in the United States. THE NORMAN LEAR CENTER is a multidisciplinary research and public policy center exploring implications of the convergence of entertainment, commerce, and society. Located at the University of Southern California, the Lear Center builds bridges among eleven schools whose faculties study aspects of entertainment, media, and culture. Beyond the campus, it bridges the gaps between the entertainment industry and academia, and between them and the public. Through scholarship and research; through its programs of visiting fellows, conferences, public events, and publications; and in its attempts to illuminate and repair the world, th^e Lear Center works to be at the forefront of discussion and praxis in the field. Contact the Lear Center by phone 213.821.1343, fax: 213.821.1580, or email ([email protected]). For more information, please visit our website at entertainment.usc.edu TELEVISION'S CHANGING IMAGE OF AMERICAN JEWS NEAL GABLER FRANK RICH JOYCE ANTLER THE AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE AND THE NORMAN LEAR CENTER Neal Gabler, a film and television critic, is a senior fellow of the Nor• man Lear Center at the USC Annenberg School for Communication. -

The Essential HBO Reader

University of Kentucky UKnowledge American Popular Culture American Studies 1-18-2008 The Essential HBO Reader Gary R. Edgerton Jeffrey P. Jones Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Edgerton, Gary R. and Jones, Jeffrey P., "The Essential HBO Reader" (2008). American Popular Culture. 15. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_american_popular_culture/15 THE ESSENTIAL HBO READER ESSENTIAL READERS IN CONTEMPORARY MEDIA AND CULTURE This series is designed to collect and publish the best scholarly writing on various aspects of television, fi lm, the Internet, and other media of today. Along with providing original insights and explorations of critical themes, the series is intended to provide readers with the best available resources for an in-depth understanding of the fundamental issues in contemporary media and cultural studies. Topics in the series may include, but are not limited to, critical-cultural examinations of creators, content, institutions, and audiences associated with the media industry. Written in a clear and accessible style, books in the series include both single-author works and edited collections. SERIES EDITOR Gary R. Edgerton, Old Dominion University THE ESSENTIAL READER Edited by Gary R. Edgerton and Jeffrey P. Jones THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.