The Christian Parody in Sara Paretsky's Ghost Country

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960 Dahnya Nicole Hernandez Pitzer College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pitzer Senior Theses Pitzer Student Scholarship 2014 Funny Pages: Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960 Dahnya Nicole Hernandez Pitzer College Recommended Citation Hernandez, Dahnya Nicole, "Funny Pages: Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960" (2014). Pitzer Senior Theses. Paper 60. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pitzer_theses/60 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pitzer Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pitzer Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FUNNY PAGES COMIC STRIPS AND THE AMERICAN FAMILY, 1930-1960 BY DAHNYA HERNANDEZ-ROACH SUBMITTED TO PITZER COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE BACHELOR OF ARTS DEGREE FIRST READER: PROFESSOR BILL ANTHES SECOND READER: PROFESSOR MATTHEW DELMONT APRIL 25, 2014 0 Table of Contents Acknowledgements...........................................................................................................................................2 Introduction.........................................................................................................................................................3 Chapter One: Blondie.....................................................................................................................................18 Chapter Two: Little Orphan Annie............................................................................................................35 -

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

October 2020

2020 Newsletter ACCLAIM HEALTH – ACTIVITY NEWSLETTER FAMOUS OCTOBER BIRTHDAYS October 1st, 1924 – Jimmy Carter was the 39th President of the United States of America, turns 95 this year! October 18th, 1919 – Pierre Trudeau was the former Prime Minister of Canada from 1980 – 1984. October 25th 1881 – Pablo Picasso was the world famous Spanish painter. He finished his first painting, The Picador at just 9 years old! ? October, 10th month October 29th 1959 – Mike Gartner, Famous Ice of the Gregorian calendar. Its name is hockey player turns 60! derived from octo, Latin for “eight,” an indication of its position in the early Roman calendar., Happy Birthday to our club membersAugustus, in celebrating their birthday’s in October 8BC,!! naming it after himself. Special dates in October Flower of the October 4th – World Smile Day month October 10th – National Cheese Day th The Flower for the October 15 – National I Love Lucy Day month is the October 28th – National Chocolate Marigold. It blooms Day in a variety of colours like red, yellow, white and orange. It stands for Creativity and symbolizes Peace and Tranquility. The Zodiac signs for October are: Libra (September 22 – October 22) Scorpio (October 23 – November 21 Movie Releases The Sisters was released on October 14th, 1938. Three daughters of a small-town pharmacist undergo trials and tribulations in their problematic marriages between 1904 and 1908. This film starred Bette Davis, Errol Flynn and Anita Louise. Have you seen it?! Songs of the month! (Click on the link below the song to listen) 1. Autumn in New York by Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong https://www.youtube.com/w atch?v=50zL8TnMBN8&featu Remember Charlie re=youtu.be Brown? “It’s the Great Pumpkin 2. -

Dick Tracy.” MAX ALLAN COLLINS —Scoop the DICK COMPLETE DICK ® TRACY TRACY

$39.99 “The period covered in this volume is arguably one of the strongest in the Gould/Tracy canon, (Different in Canada) and undeniably the cartoonist’s best work since 1952's Crewy Lou continuity. “One of the best things to happen to the Brutality by both the good and bad guys is as strong and disturbing as ever…” comic market in the last few years was IDW’s decision to publish The Complete from the Introduction by Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy.” MAX ALLAN COLLINS —Scoop THE DICK COMPLETE DICK ® TRACY TRACY NEARLY 550 SEQUENTIAL COMICS OCTOBER 1954 In Volume Sixteen—reprinting strips from October 25, 1954 THROUGH through May 13, 1956—Chester Gould presents an amazing MAY 1956 Chester Gould (1900–1985) was born in Pawnee, Oklahoma. number of memorable characters: grotesques such as the He attended Oklahoma A&M (now Oklahoma State murderous Rughead and a 467-lb. killer named Oodles, University) before transferring to Northwestern University in health faddist George Ozone and his wild boys named Neki Chicago, from which he was graduated in 1923. He produced and Hokey, the despicable "Nothing" Yonson, and the amoral the minor comic strips Fillum Fables and The Radio Catts teenager Joe Period. He then introduces nightclub photog- before striking it big with Dick Tracy in 1931. Originally titled Plainclothes Tracy, the rechristened strip became one of turned policewoman Lizz, at a time when women on the the most successful and lauded comic strips of all time, as well force were still a rarity. Plus for the first time Gould brings as a media and merchandising sensation. -

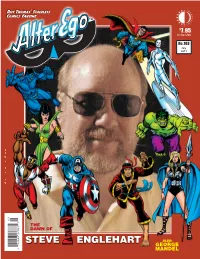

Englehart Steve

AE103Cover FINAL_AE49 Trial Cover.qxd 6/22/11 4:48 PM Page 1 BOOKS FROM TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Roy Thomas’ Stainless Comics Fanzine $7.95 In the USA No.103 July 2011 STAN LEE UNIVERSE CARMINE INFANTINO SAL BUSCEMA MATT BAKER The ultimate repository of interviews with and PENCILER, PUBLISHER, PROVOCATEUR COMICS’ FAST & FURIOUS ARTIST THE ART OF GLAMOUR mementos about Marvel Comics’ fearless leader! Shines a light on the life and career of the artistic Explores the life and career of one of Marvel Comics’ Biography of the talented master of 1940s “Good (176-page trade paperback) $26.95 and publishing visionary of DC Comics! most recognizable and dependable artists! Girl” art, complete with color story reprints! (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 (224-page trade paperback) $26.95 (176-page trade paperback with COLOR) $26.95 (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 QUALITY COMPANION BATCAVE COMPANION EXTRAORDINARY WORKS IMAGE COMICS The first dedicated book about the Golden Age Unlocks the secrets of Batman’s Silver and Bronze OF ALAN MOORE THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE publisher that spawned the modern-day “Freedom Ages, following the Dark Knight’s progression from Definitive biography of the Watchmen writer, in a An unprecedented look at the company that sold Fighters”, Plastic Man, and the Blackhawks! 1960s camp to 1970s creature of the night! new, expanded edition! comics in the millions, and their celebrity artists! (256-page trade paperback with COLOR) $31.95 (240-page trade paperback) $26.95 (240-page trade paperback) $29.95 (280-page trade -

The Inventory of the Harold Gray Collection #100

The Inventory of the Harold Gray Collection #100 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Gray, Harold #100 Gifts of Mrs. Harold Gray and others, 1966-1992 Box 1 Folder 1 I. Correspondence. A. Reader mail. 1. Fan mail re: “Little Orphan Annie.” a. 1937. b. 1938. c. 1939. d. Undated (1930s). Folder 2 e. 1940-1943. Folder 3 f. 1944. Folder 4 g. 1945. Folder 5 h. 1946. Folder 6 i. 1947. Folder 7 j. 1948. Folder 8 k. 1949. 2 Box 1 cont’d. Folder 9 l. Undated (1940s). Folder 10 m. 1950. Folder 11 n. 1951. Folder 12 o. 1952. Folder 13 p. 1953-1955. Folder 14 q. 1957-1959. Folder 15 r. Undated (1950s). Folder 16 s. 1960. Folder 17 t. 1961. Folder 18 u. 1962. Folder 19 v. 1963. 3 Box 1 cont’d. Folder 20 w. 1964. Folder 21 x. 1965. Folder 22 y. 1966. Folder 23 z. 1967. Folder 24 aa. 1968. Folder 25 bb. Undated (1960s). Folder 26 2. Reader comments, criticisms and complaints. a. TLS re: depiction of social work in “Annie,” Mar. 3, 1937. Folder 27 b. Letters re: “Annie” character names, 1938-1966. Folder 28 c. Re: “Annie”’s dress and appearance, 1941-1952. Folder 29 d. Protests re: African-American character in “Annie,” 1942; includes: (i) “Maw Green” comic strip. 4 Box 1 cont’d. (ii) TL from HG to R. B. Chandler, publisher of the Mobile Press Register, explaining his choice to draw a black character, asking for understanding, and stating his personal stance on issue of the “color barrier,” Aug. -

Local Exhibit Highlights Work of Self-Taught Southern Artist Felicia Feaster

July 9, 2020 Local Exhibit Highlights Work of Self-Taught Southern Artist Felicia Feaster Enjoyment of self-taught art may depend on how much you want to swim around in another human being’s headspace. Are you in the mood to contemplate the conditions that foster both creativity, but also the darker byways of obsession and personal experience? With much art, it is possible to separate the maker from her work. You can glide across the pleasures of surface, technique and subject matter. But self-taught art gives you no such opportunity or out; part of the bargain is, in fact, a deep dive into biography. And in the Atlanta Contemporary show “The Life and Death of Charles Williams,” there’s no getting around the strange, fascinating and sometimes troubling reality of this Kentucky artist’s life. There is both joy and pain in Williams’ experience, and in his art. It’s hard not to revel in the unique point of view of this utterly idiosyncratic Black Southern artist while also feeling saddened by his circumstance and limitations. Like so many self-taught artists, Williams defiantly marched to his own arrhythmic beat. He spent a lifetime making art that acted out the kind of dramas of might and right that children cling to: art fueled by comic book tales of brawny, powerful, justice-minded superheroes with cut-glass jawlines, tree trunk thighs and hyper-articulated Tom of Finland musculature. In fact, Williams learned to draw, like so many kids, by rendering favorite heroes like Dick Tracy and Superman. But while kids eventually give up those superficial parables of good and evil, Williams clung to them. -

Putting It Together

46th Season • 437th Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / September 11 - October 11, 2009 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing ArtiStic director ArtiStic director presents PUTTING IT TOGETHER words and music by Stephen Sondheim devised by Stephen Sondheim and Julia McKenzie Thomas Buderwitz Soojin Lee Steven Young Drew Dalzell Scenic deSign coStume deSign Lighting deSign Sound deSign Joshua Marchesi Jamie A. Tucker* Production mAnAger StAge mAnAger musical direction by Dennis Castellano directed by Nick DeGruccio Dr. S.L. and Mrs. Betty Eu Huang Huang Family Foundation honorAry ProducerS corPorAte Producer Putting It Together is presented through special arrangement with music theatre international (mti). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by mti. 421 West 54th Street, new york, ny 10019; Phone: 212-541-4684 Fax: 212-397-4684; www.mtiShows.com Putting It Together• SOUTH COA S T REPE R TO R Y P1 THE CAST (in order of appearance) Matt McGrath* Harry Groener* Niki Scalera* Dan Callaway* Mary Gordon Murray* MUSICIANS Dennis Castellano (conductor/keyboards), John Glaudini (synthesizer), John Reilly (woodwinds), Louis Allee (percussion) SETTING A New York penthouse apartment. Now. LENGTH Approximately two hours including one 15-minute intermission. PRODUCTION STAFF Casting ................................................................................ Joanne DeNaut, CSA Dramaturg .......................................................................... Linda Sullivan Baity Assistant Stage Manager ............................................................. -

Faces Illustration Featuring, in No 1

face Parigi Books is proud to present fās/ a selection of carefully chosen noun original comic art and noun: face; plural noun: faces illustration featuring, in no 1. particular order, the front part of a person's Virgil Finlay, John Romita, John Romita, Jr, Romano Scarpa, head from the forehead to the Milo Manara, Magnus, Simone chin, or the corresponding part in Bianchi, Johnny Hart, Brant an animal. Parker, Don Rosa, Jeff MacNelly, Russell Crofoot, and many others. All items subject to prior sale. Enjoy! Parigi Books www.parigibooks.com [email protected] +1.518.391.8027 29793 Bianchi, Simone Wolverine #313 Double-Page Splash (pages 14 and 15) Original Comic Art. Marvel Comics, 2012. A spectacular double-page splash from Wolverine #313 (pages 14 and 15). Ink and acrylics on Bristol board. Features Wolverine, Sabretooth, and Romulus. Measures 22 x 17". Signed by Simone Bianchi on the bottom left corner. $2,750.00 30088 Immonen, Stuart; Smith, Cam Fantastic Four Annual #1 Page 31 Original Comic Art. Marvel Comics, 1998. Original comic art for Fantastic Four Annual #1, 1998. Measures approximately 28.5 x 44 cm (11.25 x 17.25"). Pencil and ink on art board. Signed by Stuart Immonen on the upper edge. A dazzling fight scene featuring a nice large shot of Crystal, of the Inhumans, the Wakandan princess Zawadi, Johnny Storm, Blastaar, and the Hooded Haunt. Condition is fine. $275.00 29474 Crofoot, Russel Original Cover Art for Sax Rohmer's Tales of Secret Egypt. No date. Original dustjacket art for the 1st US edition of Tales of Secret Egypt by Sax Rohmer, published by Robert McBride in 1919, and later reprinted by A. -

Commies, H-Bombs and the National Security State: the Cold War in The

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® History Faculty Publications History 1997 Commies, H-Bombs and the National Security State: The oldC War in the Comics Anthony Harkins Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/history_fac_pubs Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Cultural History Commons, and the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Anthony Harkins, “Commies, H-Bombs and the National Security State: The oC ld War in the Comics” in Gail W. Pieper and Kenneth D. Nordin, eds., Understanding the Funnies: Critical Interpretations of Comic Strips (Lisle, IL: Procopian Press, 1997): 12-36. This Contribution to Book is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Harkins 13 , In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the U.S. government into the key components of what later historians would dub the "national securi ty state." The National Security Act of 1947 established a of Defense, the Central Intelligence Agency, and the National Security Council. The secret "NSC-68" document of 1950 advocated the development of hydrogen bomb, the rapid buildup of conventional forces, a worldwide sys tem of alliances with anti-Communist governments, and the unpn~ce'Clent€~CI mobilization of American society. That document became a blueprint for waging the cold war over the next twenty years. These years also saw the pas sage of the McCarran Internal Security Act (requiring all Communist organizations and their members to register with the government) and the n the era of Ronald Reagan and Newt Gingrich, some look back upon the rise of Senator Joseph McCarthy and his virulent but unsubstantiated charges 1950s as "a age of innocence and simplicity" (Miller and Nowak of Communists in the federal government. -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Copyright Service. sydney.edu.au/copyright PROFESSIONAL EYES: FEMINIST CRIME FICTION BY FORMER CRIMINAL JUSTICE PROFESSIONALS by Lili Pâquet A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Sydney 2015 DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I hereby certify that this thesis is entirely my own work and that any material written by others has been acknowledged in the text. The thesis has not been presented for a degree or for any other purposes at The University of Sydney or at any other university of institution. -

The Sisters in Crime Newsletter

InSinC The Sisters in Crime Newsletter Volume XX • Number 3 September 2007 SinC Slate for 2007–2008 By Libby Hellmann My last official act for SinC happens to be the mysteries have been nominated for both Agatha Kathryn Wall — Treasurer. Kathy will most satisfying one — introducing next year’s and Anthony awards. Having partially recovered continue her stellar performance in the appoint- slate of national officers. We have an especially from her golf obsession, Roberta saw the debut ed position of SinC strong slate this year with both seasoned veter- of a new series in March 2007, beginning with Treasurer. Kathy is ans and “young Turks,” and I’m confident the Deadly Advice, featuring psychologist/advice well qualified, having organization will be in good hands. I hope you’ll columnist Dr. Rebecca Butterman. Roberta lives been an accountant agree by electing them as your leaders. in Madison, CT. for many years before Roberta Isleib, current Vice President, is the Judy Clemens — Vice President. Formerly taking early retirement nominee for President. Judy Clemens is running a professional stage manager, Judy is the author to write full-time. She for Vice President. Marcia Talley will continue as of a series featuring self-published her first Secretary, and Kathy Wall will continue as Trea- dairy farmer and Har- Bay Tanner mystery, In surer, an appointed and non-voting position. In ley-enthusiast Stella for a Penny, in 2001. addition Jim Huang, our Bookstore Liaison, and Crown. Her Anthony The series was subse- Donna Andrews, Chapter Liaison will be with and Agatha award quently picked up by us once again.